A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

LA: I have to look at the

role. Even maestro Merola asked me to sing Tosca. I said, "Let's wait a

little more for Tosca.

She's very, very

dramatic in action, not vocally because

if you have high notes, the second act's okay. If you

don't have it you scream, and that's terrible. [Laughter]

The most dramatic thing is in the duet

with Scarpia, and it is dramatic even to the last touch, and later to

describe again what she did with Scarpia when she killed him.

Usually they don't make all the same reactions

like they did in second act. When you see a movie and then

somebody tells you the story, they come in and tell you what

happened. So I used to do that the last act of Tosca this

way. I did the same staging, the same movements I did when I

killed Scarpia to show Mario what I did. That becomes

dramatic, too. But I think the dramatic comes when you really not

just push the voice, because then

the voice stops; it doesn't go on to the audience. It

isn't just to have this kind of beautiful shining voice; it must

project. We had so many artists that had voices that were smaller

than mine — Schipa, for

example, or Cesare Valletti, or Gigli.

They were lyric. Cesare Valletti and Schipa were leggiero, light,

and you could hear those voices even at the back of the opera.

That means they never pushed; they just left the voice floating.

That's what

I tell to the young people when I see them, "Why don't you

make your voice float in the theater?" Not to do [vocalizes in a

coarse, constricted, and unsophisticatedly undulating tone] "Uhhhhhh,"

where you push and you keep the breath in the

back. Instead, the breath should come out. You need to

do [demonstrates singing in a light, relaxed tone of voice]

"Ahhhhh." [Demonstrates the same thing, starting

more softly and gradually increasing in volume]

"Ahhhhhhhhhhhhh." This goes because the note is on the

breath. I don't see them because I don't teach; I try to

teach, but I couldn't. I want to be free. I need to do a

lot of things. I don't know if you heard, I sang the Follies

here in New York two years ago, and then I sang it in Houston for a

month. I was there the month of June, and they enjoyed it so much.

LA: I have to look at the

role. Even maestro Merola asked me to sing Tosca. I said, "Let's wait a

little more for Tosca.

She's very, very

dramatic in action, not vocally because

if you have high notes, the second act's okay. If you

don't have it you scream, and that's terrible. [Laughter]

The most dramatic thing is in the duet

with Scarpia, and it is dramatic even to the last touch, and later to

describe again what she did with Scarpia when she killed him.

Usually they don't make all the same reactions

like they did in second act. When you see a movie and then

somebody tells you the story, they come in and tell you what

happened. So I used to do that the last act of Tosca this

way. I did the same staging, the same movements I did when I

killed Scarpia to show Mario what I did. That becomes

dramatic, too. But I think the dramatic comes when you really not

just push the voice, because then

the voice stops; it doesn't go on to the audience. It

isn't just to have this kind of beautiful shining voice; it must

project. We had so many artists that had voices that were smaller

than mine — Schipa, for

example, or Cesare Valletti, or Gigli.

They were lyric. Cesare Valletti and Schipa were leggiero, light,

and you could hear those voices even at the back of the opera.

That means they never pushed; they just left the voice floating.

That's what

I tell to the young people when I see them, "Why don't you

make your voice float in the theater?" Not to do [vocalizes in a

coarse, constricted, and unsophisticatedly undulating tone] "Uhhhhhh,"

where you push and you keep the breath in the

back. Instead, the breath should come out. You need to

do [demonstrates singing in a light, relaxed tone of voice]

"Ahhhhh." [Demonstrates the same thing, starting

more softly and gradually increasing in volume]

"Ahhhhhhhhhhhhh." This goes because the note is on the

breath. I don't see them because I don't teach; I try to

teach, but I couldn't. I want to be free. I need to do a

lot of things. I don't know if you heard, I sang the Follies

here in New York two years ago, and then I sang it in Houston for a

month. I was there the month of June, and they enjoyed it so much. LA: First I read the

book, if there is a book, of the opera that I always sing. When I

did Donna Anna or Nozze di Figaro,

we have books of these

beautiful roles. With Manon, I read the book. I find the

Manon of Massenet very

French, elegant like a powder puff. [Chuckles] When

I study the Puccini, Puccini was Puccini, dramatic

and Italian. But I read the book and I found out very much.

For instance, des Grieux was a very, very stubborn man! This is

like a Sicilian mind, like where I

come from in Southern Italy! Very,

very stubborn. I find out the two operas had the

same thing — light and then dramatic. In

Manon

of Massenet, you cannot put something dramatic like Puccini did in

the last act with "Sola, perduta,

abbandonata." This is a heavy,

beautiful aria. That's the

difference. The Massenet opera is very light, very chic, but both

of them are beautiful.

LA: First I read the

book, if there is a book, of the opera that I always sing. When I

did Donna Anna or Nozze di Figaro,

we have books of these

beautiful roles. With Manon, I read the book. I find the

Manon of Massenet very

French, elegant like a powder puff. [Chuckles] When

I study the Puccini, Puccini was Puccini, dramatic

and Italian. But I read the book and I found out very much.

For instance, des Grieux was a very, very stubborn man! This is

like a Sicilian mind, like where I

come from in Southern Italy! Very,

very stubborn. I find out the two operas had the

same thing — light and then dramatic. In

Manon

of Massenet, you cannot put something dramatic like Puccini did in

the last act with "Sola, perduta,

abbandonata." This is a heavy,

beautiful aria. That's the

difference. The Massenet opera is very light, very chic, but both

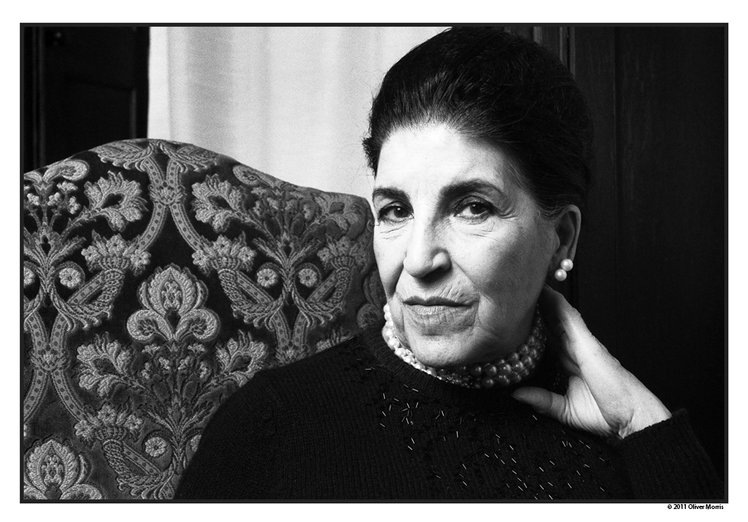

of them are beautiful.| Italian soprano. Born July 22,

1913, in Bari, Italy; m. Joseph Gimma (Italian-American businessman),

1945; studied with Emanuel De Rosa in Bari and Giuseppina

Baldassare-Tedeschi in Milan. At 22, won 1st Italian government-sponsored vocal competition in a field of 300 entrants; in 1st five years of career, sang at Teatro alla Scala, Covent Garden, and the Rome Opera; when Benito Mussolini would no longer let distinguished Italian artists leave the country, escaped to Portugal (1939) and boarded ship bound for US; debuted at Metropolitan Opera (Feb 9, 1940) as Cio-Cio-San; was perhaps the most famous La Boheme Mimi of the 1940s; made final Metropolitan Opera performance (1966); received the Lady Grand Cross of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre from Pope Pius XII; after retirement, worked for Puccini Foundation, founded by husband, to further survival of opera as art form; awarded President’s Medal by Bill Clinton for work in the arts (1995). ======== Albanese was one of the most beloved sopranos in the Italian repertoire, specializing in roles that suited her physical and vocal appearances of vulnerability and delicacy. She specialized in Puccini, and was associated with his Madama Butterfly more than with any other role. Her vocal and dramatic intensity and sense of apt staging made her performances riveting. She first studied piano, but switched her energies to voice, studying with Giuseppina Baldassare-Tedeschi. She won the Italian National Singing Competition in 1933, and her opera debut, as Butterfly, was as a mid-opera last-minute substitute for an ailing colleague at the Teatro Lirico in Milan, in 1934. Her La Scala debut was in 1935 as Lauretta in Puccini's Gianni Schicchi, her Covent Garden debut as Liu in Turandot, and her Met debut was in 1940 as Butterfly, beginning an association with that house that lasted until 1966. She made the occasional forays into heavier repertoire during her career, even experimenting with the role of Elsa in Lohengrin in her early years in Italy, but rarely added such roles to her repertoire, and being careful with her performances of even such medium-weight roles as Tosca. Towards the end of her career, she performed heavier roles such as Aida. After her retirement, she remained active, leading the Puccini Foundation (which she and her husband created), teaching master classes at the Juilliard School of Music and Marymount Manhattan College, and directing operatic scenes. In 1985 and 1987, she made cameo appearances in Steven Sondheim's Follies. In 2000, she received the Handel Medallion. The honor, which was bestowed upon her by Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani, is a tribute to individuals who have enriched New York City's cultural life. |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on

February 26, 1988. A portion was published in The Massenet Newsletter in July,

1989, and

other sections were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1998.

It was fully transcribed, re-edited and posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.