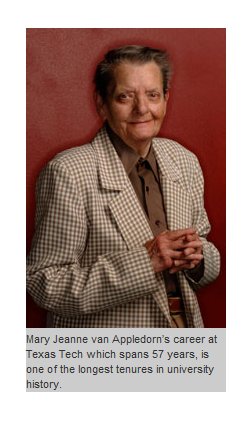

| Mary Jeanne van Appledorn was

born October 2, 1927 in Holland, Michigan, to John and Elizabeth van

Appledorn. Neither of her parents were professional musicians; her

father was, however, organist of the Ninth Street Christian Reformed

Church and active in music circles in Holland. As a child, van

Appledorn studied piano, as did her older sister Ruth. Following the

death of her father in 1944, she and her mother moved to Topeka, Kansas

(where her sister was a music teacher at Alma College) for van

Appledorn's senior year of high school. Van Appledorn graduated from

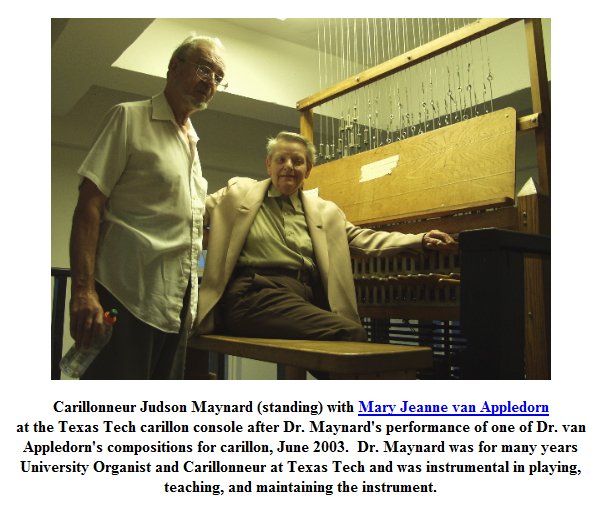

Topeka High School in 1945 as valedictorian. Van Appledorn studied both piano and theory at the University of Rochester's prestigious Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. Van Appledorn earned the George Eastman Honorary Scholarship each year, and in 1948 received her Bachelor of Music with Distinction (piano); she studied under Cecile Straub Genhart. Van Appledorn received her Master of Music Degree (theory) from the Eastman School of Music in 1950; from 1948 she was a Teaching Fellow of the Eastman School of Music. In the fall of 1950 Van Appledorn accepted a position at Texas Technological College (now Texas Tech University). She received her Ph.D. (music) from the Eastman School of Music in 1966, and was awarded a Graduate Fellowship from 1961-1962. She was also awarded the Delta Kappa Gamma International Scholarship from 1959-1960; one of three awards granted to outstanding women for furthering and completing the doctorate degree. Dr. van Appledorn's dissertation for this degree is titled A Stylistic Study of Claude Debussy's Opera Pelleas et Melisande (completed in 1965). During her studies at Eastman, Dr. van Appledorn received training in composition from renowned composers Bernard Rogers and Alan Hovhaness. In 1982 Dr. van Appledorn was one of nine faculty members of Texas Tech University to receive a faculty development leave, during which she studied computer-synthesized sound techniques at the Studio for Experimental Music, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Dr. Barry Vercoe, professor. As an educator, Dr. van Appledorn taught at Texas Tech University from 1950-2008. Dr. van Appledorn taught a wide range of courses during this time, from undergraduate music theory to graduate composition courses. Dr. van Appledorn served as chairman of the Division of Music Literature and Theory (1950-1968) in the school of music, and played an important role in the development of the curriculum of the undergraduate and graduate music degrees, alongside Chairman of the School of Music, Gene Hemmle. Dr. van Appledorn also served as chairman of the Graduate Studies Committee of the Department of Music. She founded and served as chairman of the annual Symposium of Contemporary Music at Texas Tech (1951-1981), and obtained the commission of many new works by renowned composers such as Dr. Howard Hanson (Streams in the Desert, 1969). In 1989 she was named a Paul Whitfield Horn Professor of Texas Tech University. As a composer, van Appledorn has had a very successful career. She composed music in many genres, both instrumental and vocal. She received her first awards for composition (Mu Phi Epsilon National Composition Contests) for Set of Five (1951) for piano and Contrasts for Piano (1953). Other honors include the Premier Prix, Dijon, awards from the Texas Composers Guild and ASCAP, and other commissions from the Music Teachers National Association and National Intercollegiate Bands. Many of Dr. van Appledorn's compositions have been published by Carl Fischer, Oxford University Press, and E.C. Schirmer Music Company, among others. Numerous recordings of her compositions have been made by world-renowned musicians and ensembles, and her music has been performed in festivals and concerts both nationally and internationally. Dr. van Appledorn has been included in a number of published biographies, not limited to: International Who's Who in Music, 10th, 11th and 12th editions, The World Who's Who of Women, ASCAP Biographical Dictionary, 4th edition, Bakers Biographical Dictionary, Scribner Music Library Dictionary of Composers, and the Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. [Another biography which lists

many of her compositions is at the bottom of this webpage.]

|

MJvA: Yes, I think

so. For one thing, they can hear their pieces immediately, scored

for the instruments and so forth; and not only those instruments, but

completely new sounds as they rev them up on the Kurzweil 250.

They have immediate results, whereas often times in the past we would

have to wait weeks before we got either a student or a faculty member

to play lines for us.

MJvA: Yes, I think

so. For one thing, they can hear their pieces immediately, scored

for the instruments and so forth; and not only those instruments, but

completely new sounds as they rev them up on the Kurzweil 250.

They have immediate results, whereas often times in the past we would

have to wait weeks before we got either a student or a faculty member

to play lines for us.

BD: And yet if

you’re inside, aren’t you too close to the large bells?

BD: And yet if

you’re inside, aren’t you too close to the large bells? MJvA: Yes, because

you don’t have quite as much chance for performances unless you’re in a

music unit of some sort. I’ve looked at that situation as a

problem with some of them. Those that are connected with

universities have a little more opportunity for performances with

orchestras or with bands or with solo works. I just have to

complete a new work and performances come pretty rapidly.

MJvA: Yes, because

you don’t have quite as much chance for performances unless you’re in a

music unit of some sort. I’ve looked at that situation as a

problem with some of them. Those that are connected with

universities have a little more opportunity for performances with

orchestras or with bands or with solo works. I just have to

complete a new work and performances come pretty rapidly. BD: Oh, yes.

I remember those.

BD: Oh, yes.

I remember those. MJvA: I don’t

know. [Laughs] People like to perform it,

apparently. I have to say that I do not have as large an output

as some persons, perhaps, comparably. I hope yet to write in some

of the very larger areas yet. I hope to address

symphonic writing, perhaps, and opera.

MJvA: I don’t

know. [Laughs] People like to perform it,

apparently. I have to say that I do not have as large an output

as some persons, perhaps, comparably. I hope yet to write in some

of the very larger areas yet. I hope to address

symphonic writing, perhaps, and opera.|

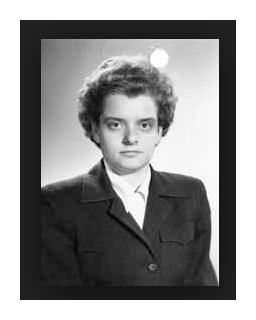

Mary

Jeanne van Appledorn

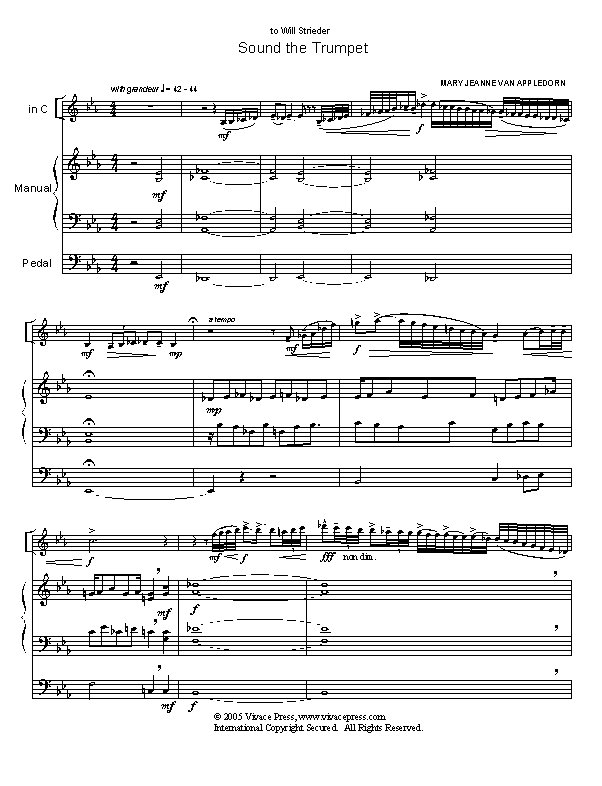

The widely-respected educator and stylistically diverse composer Mary Jeanne van Appledorn was born October 2, 1927 in Holland, Michigan. She graduated (as valedictorian) in 1945 from Topeka High School, Topeka, Kansas. She received her Bachelor of Music (with Distinction) in Piano at the Eastman School of Music, Rochester, New York, in 1948, and was awarded George Eastman Honorary Scholarships each year; her Master's degree in Music Theory followed in 1950, and she received teaching fellowships between 1948-50. She received her PhD in Music from Eastman in 1966. Her primary teachers at Eastman were Bernard Rogers and Alan Hovhaness. She is presently on the music faculty at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas, where she has taught since 1950. Her earliest listed composition dates from 1947, her Contrasts for piano, a group of three homages in the styles of Bartók, Bloch, and William Schuman. The work received the Mu Phi Epsilon National Composition Contest. In 1948 she wrote Cellano Rhapsody for cello and piano, which was recorded by CRS Inc. Her Two Shakespeare Songs for choir and piano (1953) received two awards: one from the Ithaca College Choral Composition Contest in 1979, and from the Southcoast Choral Society of California in 1985. Her Set of Five for piano received a Mu Phi Epsilon award and was recorded by Opus One Records (#52) featuring the composer as pianist. Her Concerto Brevis for piano and orchestra followed the next year, and her Patterns for French Horn Quintet was written in 1956; this surprising work was released on a recent Opus One CD (#162). Her Concerto for Trumpet and Band (1960) was premiered in the USSR in 1986, and in Budapest, Hungary in 1987; it has been recorded on an Opus One LP (#110) by Robert M. Birch and the Texas Tech University Symphonic Band. Her Passacaglia and Chorale for orchestra was composed in 1973 and was a finalist in the NSOA/Scherle & Roth Orchestra Composition Contest in 1979; it is available on the same Opus One LP (#110). The year 1976 saw two important works: the West Texas Suite for chorus, symphonic band and percussion ensemble (commissioned by the Lubbock Independent School District for the Lubbock Bicentennial Choral Concert in that year; and her award-winning Suite for Carillon which received the Premier Prix at Dijon, France in 1980.) The large-scale cantata Rising Night After Night for choirs, three soloists, narrator and orchestra was composed in 1978 and premiered the following year at Texas Tech University. It has been recorded in the Vienna Modern Masters Series (#3004) by the Slovak Radio Orchestra of Bratislava, conducted by Oliver Dohnanyi. Her Matrices for saxophone and piano (1979) received the Texas composers Guild Award for 1980, and was recorded on Golden Crest Records by Dale Underwood and the composer. Her 1980 Symphony for Wind Ensemble, percussion and toys was commissioned by the Women Band Directors National Association and recorded by Golden Crest Records. It received the Virginia College Band Directors National Association Award. The same year saw her Azaleas for baritone solo, flute and piano, which received the Petit Jean International Art Song Festival Award in 1984. Her Lux: Legend of Sankta Lucia for symphonic band, harp, percussion ensemble and handbells was commissioned by National Intercollegiate Bands in 1981 and it received the Virginia College Band Directors Award in 1982. One of her most unusual works, Liquid Gold for saxophone and piano was composed in that year, and received its premiere at the 1982 World Saxophone Congress, Nuremberg GFR. It received the American Society of University Composers Award in 1982 and Premio Ancona (Italia) Award in 1986. It has been recorded on an Opus One CD (#147). Her A Celestial Clockwork for carillon followed in 1983, and in the next year A Liszt Fantasie for piano which received awards from Bradley University and Composers and Songwriters International Composition Contest. It has been recorded by Max Lifchitz on a North/South Consonance CD. Her Four Duos for viola and cello (1986) won First Prize fro the Texas Composers Guild in 1987. Her 1987 work for harp, Sonic Mutation was premiered in New York in that year and was recorded by the Contemporary Record Society, and her Missa Brevis for voice, trumpet, and organ (also brass Quintet) was premiered in the USSR. The following year saw a variety of new pieces including the Caprice for carillon which was premiered at the Riverside Church in New York City by James Lawson, Sonatine for clarinet and piano premiered at Carnegie Hall, New York City, a ballet, Set of Seven was premiered by New York City Ballet Company at Lincoln Center, a work for mixed chorus and organ, Love Divine, All Love Excelling and five short pieces for unaccompanied trumpet, Cornucopia rounded out the year. The year 1992 saw two dramatic works: her Incantations for trumpet and piano was commissioned by North Dakota State University and premiered there and later recorded on an Opus One CD (#162); and the excellent Terrestrial Music. A double concerto for violin solo, piano solo and string orchestra received its premiere in Nagano, Japan and a later performance at the Columbia University Miller Theatre in New York. The 1993 Atmospheres for trombone ensemble was recorded by Opus One (#169); also that year her Postcards to John for guitar was composed and the next year received the Guitar Foundation of America Award. The year 1994 also saw the genesis of her Rhapsody for trumpet and harp, also recorded on Opus One (#169); Les Hommes Vides (from T.S.Eliot's The Hollow Men) for unaccompanied chorus; Sound the Trumpet for trumpet and organ, and the very colorful and brilliant Reeds Afire for clarinet and piano. Cycles of Moons and Tides for symphonic band was commissioned in 1995 for the 50th Anniversary of Tau Beta Sigma and received a lively recording on Opus One (#170); in the same year came an organ work Variations on Jerusalem the Golden, the very intelligent Trio Italiano for trumpet, horn and bass trombone; and a setting of a Kay Scully poem, Legacy, for bass baritone and piano. The Trio Italiano received the International Trumpet Guild Award for 1996 in Long Beach, California; and a new work, Passages for trombone and piano received its world premiere at the International Trombone Festival in Feldkirch, Austria. -- Biography by Philip

Krumm (slightly edited)

-- Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

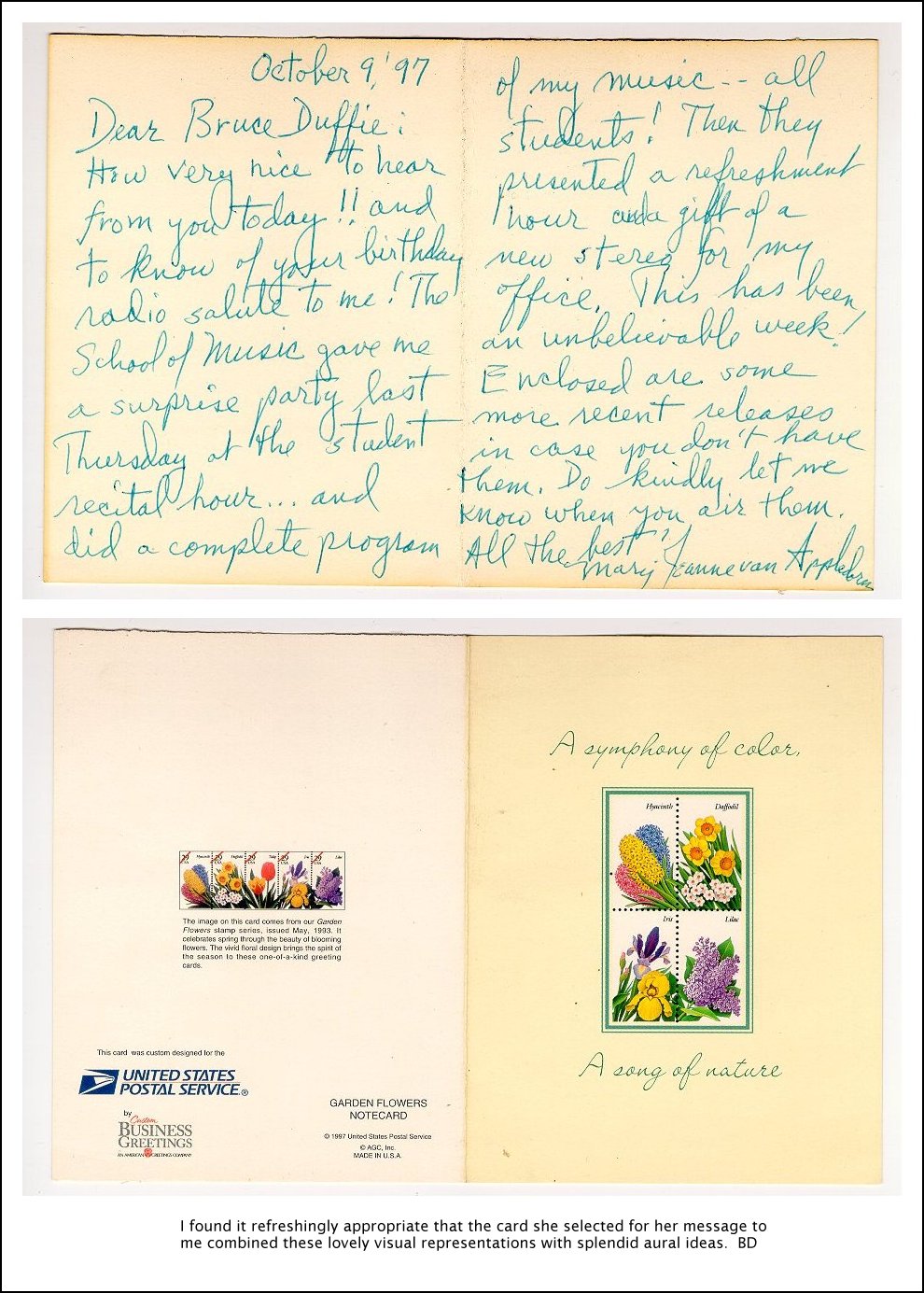

This interview was recorded on the telephone on January 20,

1988. Portions

were used (with recordings) on WNIB later that year, and again in 1992

and 1997. A

copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. The

transcript was made and posted on this

website in 2014.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.