BD: The Brazilian Psalm is also recorded on

the Gasparo disc with a different choir. Is that a better

recording, or again just different?

BD: The Brazilian Psalm is also recorded on

the Gasparo disc with a different choir. Is that a better

recording, or again just different? JB: I would rather

have taught music history because my academic training was in

that. I also felt much freer in forming my own views so far as

contemporary idioms are concerned by not teaching composition.

For example, since you do know some of my works, with the exception of

a very brief period when I was quite young and was definitely under the

impact of the then new teaching of Arnold Schoenberg regarding the

twelve-tone method for perhaps a year or so, I affiliated myself with

that. But then for a very precise reason, which I have to

describe to you, I gave it up, and ever since I was very negative about

all of that. Now I could not very well teach composition at the

university and say that in twentieth century we have met some important

names like Prokofiev, Samuel Barber, and then make some fleeting

reference that there was also the Viennese composer by the name of

Arnold Schoenberg. But forget about him, he doesn’t really matter!

JB: I would rather

have taught music history because my academic training was in

that. I also felt much freer in forming my own views so far as

contemporary idioms are concerned by not teaching composition.

For example, since you do know some of my works, with the exception of

a very brief period when I was quite young and was definitely under the

impact of the then new teaching of Arnold Schoenberg regarding the

twelve-tone method for perhaps a year or so, I affiliated myself with

that. But then for a very precise reason, which I have to

describe to you, I gave it up, and ever since I was very negative about

all of that. Now I could not very well teach composition at the

university and say that in twentieth century we have met some important

names like Prokofiev, Samuel Barber, and then make some fleeting

reference that there was also the Viennese composer by the name of

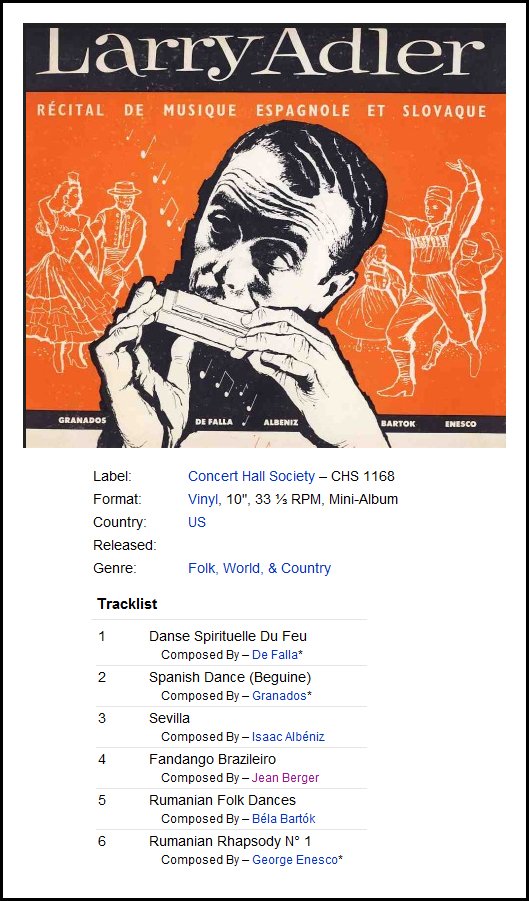

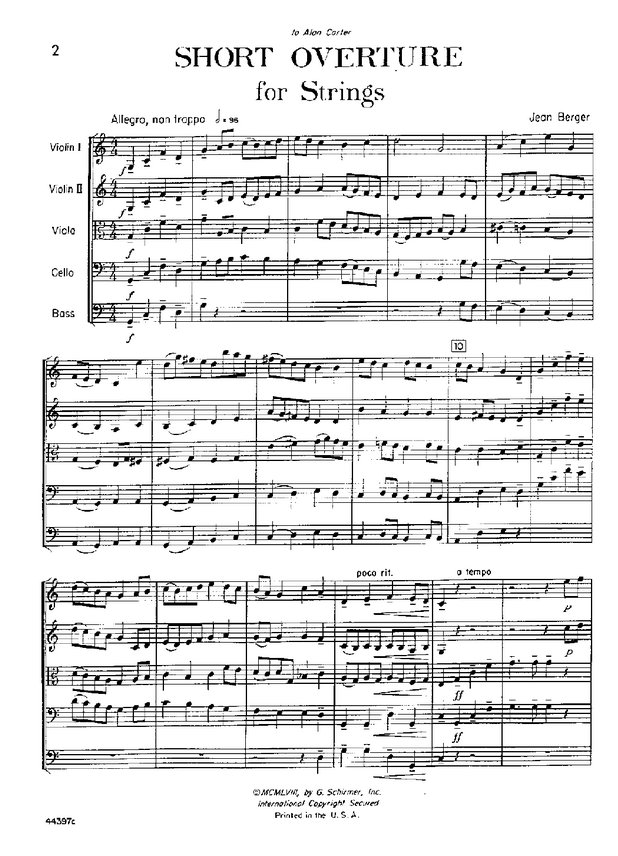

Arnold Schoenberg. But forget about him, he doesn’t really matter! BD: You’ve written

mostly choral works, but also some instrumental works. I want to

be sure and ask you about the concerto you wrote for harmonica.

BD: You’ve written

mostly choral works, but also some instrumental works. I want to

be sure and ask you about the concerto you wrote for harmonica. JB: Yes. You

don’t know me personally so you’ll have to take it at

face value, but I get so excited about somebody wanting to do my

works. I can be the most lenient composer of them all. I

began

thinking of myself as a composer extremely late in life, and to a

certain extent it is still marvelous. I never had planned to be a

composer, and to think there are these good people who, without knowing

me and without anybody helping me by manner of an agency, would simply

do my stuff. This is terribly exciting, so it will have to be

pretty

God-awful before I’m displeased. Basically I have been

pleased. There

are the really terrible performances, but frankly, recently I’ve been

lucky in having heard many more of them and what I hear is usually very

inspiring... although it may be quite different from what I would be

doing myself. As long as I recognize the music or hear the

enthusiasm

of the singers and of the players, it makes my day and I feel very

happy!

JB: Yes. You

don’t know me personally so you’ll have to take it at

face value, but I get so excited about somebody wanting to do my

works. I can be the most lenient composer of them all. I

began

thinking of myself as a composer extremely late in life, and to a

certain extent it is still marvelous. I never had planned to be a

composer, and to think there are these good people who, without knowing

me and without anybody helping me by manner of an agency, would simply

do my stuff. This is terribly exciting, so it will have to be

pretty

God-awful before I’m displeased. Basically I have been

pleased. There

are the really terrible performances, but frankly, recently I’ve been

lucky in having heard many more of them and what I hear is usually very

inspiring... although it may be quite different from what I would be

doing myself. As long as I recognize the music or hear the

enthusiasm

of the singers and of the players, it makes my day and I feel very

happy!

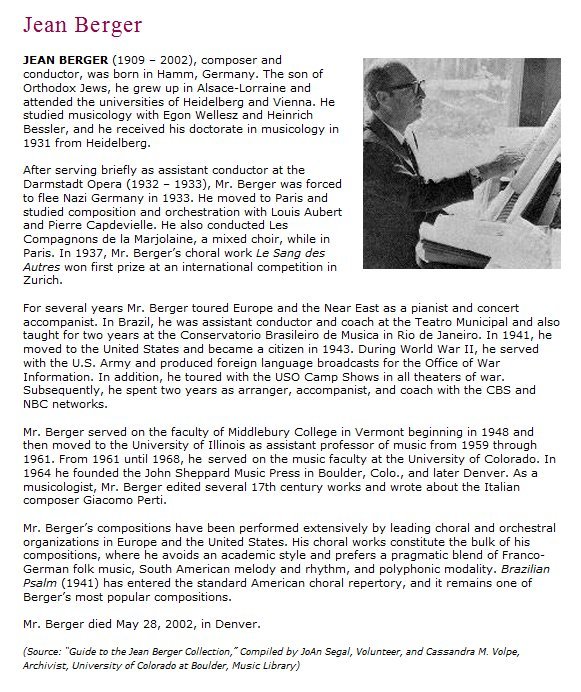

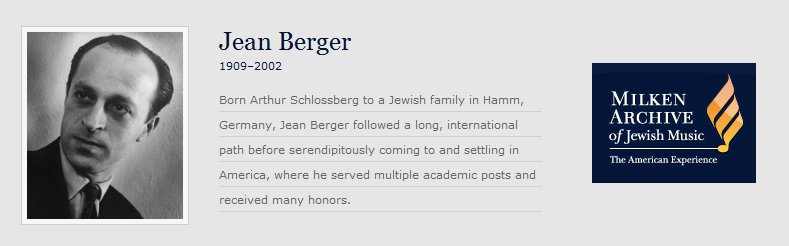

Born to a Jewish family in Hamm, Germany, a modest city in Westphalia, and originally named Arthur Schlossberg (which he changed in the 1930s), Berger’s academic music studies centered initially around musicology, which he pursued at the Universities of Vienna and Heidelberg under the tutelage of two of the founding pillars of the modern discipline, Egon Wellesz and Heinrich Besseler. At the same time, he became an accomplished pianist and acquired conducting skills as well. After receiving his doctorate in Heidelberg, he accepted a post as assistant conductor at the major opera house in Mannheim, where he also studied composition with Hugo Adler—the chief cantor of that city’s principal Liberale, or mainstream nonorthodox, synagogue and a highly regarded composer and teacher. As a Jew visible in a German cultural institution during the doomed waning days of the Weimar democracy, the young Schlossberg was almost instantly a target of local Nazi party followers—even before the party came officially to power as a result of the elections that gave no party a clear majority and resulted in the National Socialists being invited to join the government. Later, in his American years, Berger would recall how four of the Nazi party thugs, known as brown shirts, assaulted him during a rehearsal and ejected him from the opera house at gunpoint. In 1933, shortly after Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor by the newly reelected president Paul von Hindenberg in an effort to form a coalition government, Schlossberg emigrated to Paris to study composition with Louis Aubert. He took the French name Jean Berger and from his new home base in Paris embarked on concert tours in Europe and the Near East as a pianist and accompanist for singers. In 1939 he left Paris for a concert tour of Brazil with a singer, and he remained in Rio de Janeiro for the next two years, serving as assistant conductor at the Theatro Municipal and joining the faculty of the Conservatório Brasileiro de Música. He also made extensive tours of other parts of South America. In 1941, a tour as accompanist to a Brazilian singer brought Berger to America. France had fallen to Germany and been occupied by the German army in 1940, while Berger was still based in Rio. When he arrived in America, his initial intention was to remain temporarily and then return to Paris after the war—certain that the Allies would be victorious and France would be liberated: “I thought that I would return to France after the victoire,“ he said in retrospect, “which was inevitable, bien entendu.” But he soon became attracted to many aspects of the new environment, including its creative possibilities and its non-European–based musics—despite some of the typical reservations of many refugees who were grounded in central European culture. He had first encountered jazz while still in Paris, where he heard the ultimately legendary Duke Ellington in a concert at the Salle Pleyel, and he had been enthralled. The American black singer Ethel Waters sang “Stormy Weather” on that program, which had further intrigued the impressionable Berger. “Whatever else was on the program faded into nothingness,” he later recalled, “compared to that song. We discussed it all night. . . . We knew we had heard something new.” Now, in the land from which Ellington’s and Waters’s music and styles had sprung, Berger was also drawn more broadly to the musical expression of American black culture and experience—not only jazz, but blues, gospel, spirituals, and other genres. Thirty years later he would articulate his recognition of “the radical impact made upon ‘idiom’ in our time, by the Afro-American irruption.” He would become convinced that, as he observed in a 1971 discursive letter, that “idiom” could “easily and gleefully integrate Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, and ‘A Bridge Over Troubled Waters’ ”—much as highbrow European art music had integrated elements from wider cultural spheres long before the modern era. But he always credited “The Duke” with having led him to these sensibilities. “My conversion at the hands of the Black Jesus” was how he once referred to Ellington’s influence on him, and he hoped that he would one day have an opportunity to “tell him myself. I shall be willing to do so on my knees.” Not long after Berger’s arrival in America, he determined to stay. “America had begun to take me to her wheat-covered bosom,” he reminisced twenty-eight years later in a letter to the well-known critic Henry Pleasants, with whom he conducted a rich and intellectually stimulating correspondence for thirty-seven years: “and I could no longer consider a return to Europe. . . . I am willing to . . . look for what there might be [in America] that is grand. And that is here, indeed. Ellington being one of the things, but there are more. And if my small efforts can contribute one ounce of stuff, so be it.” It was not that he lacked nostalgia for prewar Europe and the refinements of its Old World cultural life, but he looked forward from the beginning to the fresh opportunities and discoveries that awaited him: “The yearning for the life that once we led is sometimes almost more than can be borne, yet my life is here.” Berger served in the United States Army beginning in 1942, and a year later he became a United States citizen. From 1943 to 1946 he produced foreign-language broadcasts for the Office of War Information and performances for USO Camp Shows for servicemen and servicewomen in various theaters of the war and areas of postwar occupation—often with his wife, Rita, a professional dancer. After a brief period spent arranging music for the CBS and NBC networks, as well as continued piano accompanying, he entered the academic world and taught until his retirement, in 1971. During those twenty-three years he was on the faculties of Middlebury College in Vermont, the University of Illinois (Champaign-Urbana), the University of Colorado, and Colorado Women’s College in Denver, where he settled permanently and continued to compose. Berger’s gift for choral writing and vocal music in general was acknowledged as early as his Paris years, when, in 1937, he was awarded first prize at an international competition in Zurich for his piece Le Sang des autres. And although over the next several decades he wrote for various instrumental as well as vocal media—including such mixed-media works as The Pied Piper, a play with music, and Birds of a Feather, an “Entertainment in One Act,” as well as orchestral pieces—he has always been most widely associated with two highly successful choral pieces: Brazilian Psalm, perhaps his most recognized work, and The Eyes of All Wait Upon Thee. Both have been part of standard repertoire of American high school and college choirs, as well as professional and amateur ensembles, for many years. Other significant choral and solo vocal works include Magnificat; Skelton Poems (1957), inspired by poetry of the Tudor-era English poet John Skelton (1460–1529); Vision of Peace; Six Madrigals; Songs of Sadness and Gladness; and, from his later years, Cantico de lo frate solo, a cycle of five songs on a text of Saint Francis of Assisi. Closest to his heart were his works for what he called “staged chorus,” the best known of which is Yiphtah and His Daughter, based on the incident in the biblical Book of Judges in which the military commander Jephta (Heb. Yiftaḥ) swears an oath that, if granted victory in battle over the Ammonites, he would sacrifice as a burnt offering to God whatever was first to emerge from his house on his return—which turned out to be his daughter. (More than one hundred musical works have been generated by this story over the centuries, including those by Handel, Schumann, Meyerbeer, and Toch.) Although composed much earlier, it was not until 1993 that Yiphtah and His Daughter was scheduled for a 1994 performance as a staged work—by the chorus of the University of Leipzig, with Berger conducting. Indeed, by the end of the 20th century, Berger concluded that his works for staged chorus constituted what he felt was his most important contribution to “the musical substance of our age.” This was, in part, an outgrowth of his developed view that the so-called traditional concert format was gradually losing its hold on American audiences and coming to an end. He saw the innovation of staged choral works as one positive solution, whereby theatrical elements were introduced into the performances. For Berger, another alternative to the traditional concert format—which he came to view largely as a holdover from a 19th-century German culturally based institution—was a workshop setting, in which a chorus would sing for itself, sometimes divided into smaller groups, rather than for a separate audience, what might be called today a “sing-in.” He believed that this kind of experimentation was made possible by the relative openness of the American environment. In a 1971 letter to Henry Pleasants he described enthusiastically such an experience with a chorus at Ashland College in Ohio, which he conducted in this format in a reading of Bach’s first motet, Sing Ye, for double choir—done without interruption as a performance for the choristers themselves, but not as a rehearsal. “No concert, but music” is how he characterized it. And he went on to affirm his certainty that “no such thing could happen in Germany, France, Italy, possibly not in Britain.” Berger was a prolific letter writer, and many of his letters to friends and colleagues offer valuable insights into his thinking and into the development of his ideas. With Henry Pleasants, he engaged in an ongoing discussion about the problems of categorizing music and the semantic as well as conceptual difficulties inherent in the various terminologies used to distinguish from all other musics what has now been accepted under the historically misleading rubric of “classical.” In the 1970s, when Berger and Pleasants were addressing this matter, the term “serious music” was in common use, probably more so than today (following other attempts, such as the 1950s “longhaired music”; “cultivated music,” which comes closest to its purpose and meaning, but never caught on, perhaps not least because it has one syllable too many; “concert music,” which lost its significance once popular, folk, jazz, and rock musicians began using the word for public performances; and “art music,” which has historical precedent but tends to sound excessively rarified—if not pretentious—and which, in any case, could apply to other musics whose very essence is the art of improvisation, not cultivation, such as jazz!). Recognizing that the label “serious” risked being misperceived in terms of relative merit, or even dismissive of other musics, Berger suggested that the German seriöse Musik—from which he presumed the English usage to have stemmed—both contained and implied nuances different from those of American sensibilities. He posited that the original German designation was born out of socioeconomic class distinctions rather than from purely aesthetic categorization. “The German music consumer of the 19th century,” he wrote, “had to demand that music be ‘serious’ because his whole Weltanschauung was predicated on this adjective. The various other terms such as Bürger (citizen), or its obverse term Künstler (artist), or the Bürger’s chief quality Pflichtbewusstsein (dutifulness) or so many others, all point in the same direction, namely a sort of Teutonic Victorianism.” Did not, he implied, this designation bestow sociological legitimacy? Moreover, he wondered whether the implied “seriousness of purpose”—i.e., an almost pretentious high-mindedness—of art music had not come about as a function of the “dissolution of the impact of religion within the 19th century,” so that the formal concert hall had become a para-religious substitute. Whether or not one agrees with any of this, the observations are certainly stimulating. Pleasants replied that the real distinction, albeit artificial, was to be found between the designations ernst Musik (serious music) and Unterhaltungsmusik (popular music)—official appellations of distinction among German radio staffs, which he called prejudicial categorization with little regard for the quality of either the music or its performance. “It nourishes snobs,” he wrote. “. . . the arts may now be the only area of human activity where snobbery is still applauded, encouraged, and even subsidized. I have no objection to music’s being taken seriously. I take it very seriously. But I don’t believe in taking only Serious Music seriously.” Berger appears to have concurred in subsequent correspondence. Other of Berger's letters yield keen observations and attitudes on a rich array of subjects, ranging from Jewish identity and inner conflicts about Zionism to the merits of serial techniques in composition, and from the small-mindedness of the academy to the nature of the art song genre, or Kunstlieder. With regard to the last, he favored performances in translation into the language of the audience. All of these discussions and deliberations help us to understand the intellect that lay behind the musical creativity of Jean Berger. After his retirement from his last full-time university post, he continued to give guest lectures as a visiting professor at colleges, universities, and conservatories in the United States and abroad. As a sort of “musical ambassador” for American culture, he spoke on American music at Oxford, Cambridge and Glasgow universities, and at schools throughout Germany, Brazil, Portugal, and Holland. And his composing continued unabated until his health began to fail. His many honors include an honorary doctorate from Pacific Lutheran University (1969) and the Colorado Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts (1985). Although his heart seems to have lain principally in composition, the musicologist within him from his early European training never disappeared entirely. He published many critical-historical editions of music by Giuseppe Torelli (1658–1709) and the 17th-century Giacomo Perti (1661–1756), as well as related articles in The Musical Quarterly and the Journal of the American Musicological Society. |

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on June 25, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.