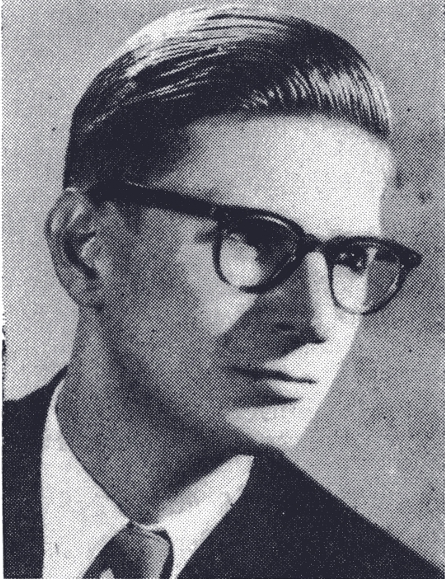

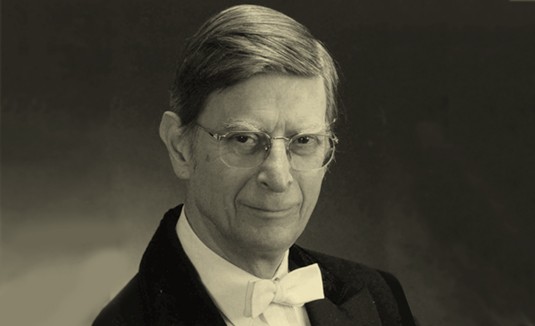

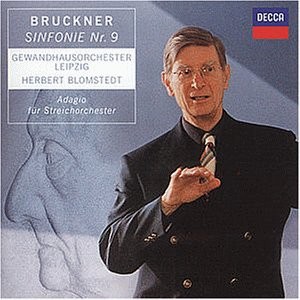

| Herbert Blomstedt (Conductor) Born: July 11, 1927 - Springfield, Massachusetts, USA The prominent American-born Swedish conductor, Herbert (Thorson) Blomstedt, was born of Swedish parents, and moved with his family to Sweden in 1929. He took courses at the Stockholm Musikhögskolan and at the University of Uppsala. After conducting lessons with Igor Markevitch in Paris, he continued his training with Jean Morel at the Juilliard School of Music in New York and with Leonard Bernstein at the Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood, where he won the Koussevitzky Prize in 1953. He also studied contemporary music in Darmstadt and renaissance and baroque music at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, and worked with Igor Markevitch in Salzburg. In February 1954 Herbert Blomstedt made his professional conducting debut with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, then was music director of the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra from 1954 to 1961. He subsequently held the post of first conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra from 1962 to 1968 while being concurrently active as a conductor with the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Copenhagen, where he served as chief conductor from 1967 to 1977. From 1975 to 1985 he was chief conductor of the Dresden Staatskapelle, with which he toured over twenty European countries, the USA (1979, 1983), and Japan. From 1977 to 1983 he was chief conductor of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Stockholm. Herbert Blomstedt also appeared as a guest conductor with principal orchestras of the world. As guest conductor, he has performed with orchestras such as the Berliner Philharmoniker, Münchner Philharmoniker, Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra and Israel Philharmonic Orchestra as well as NHK Symphony, of which he is Honorary Conductor. Herbert Blomstedt is Conductor Laureate of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra where he served as Music Director from 1985 to 1995, leading it at its 75th-anniversary gala concert in 1986 and on a tour of Europe in 1987. Throughout his tenure he and the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra repeatedly appeared to critical acclaim at major European concert venues and festivals including Edinburgh, Salzburg, Munich and Lucerne. From 1996 to 1998, he was Music Director of the NDR Sinfonieorchester Hamburg. With the season 1998-1999 he succeeded Kurt Masur as Music Director of the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, a post which he maintained until the end of the season 2004-2005. Having been appointed Honorary Conductor of this orchestra, he returns to Leipzig regularly. In 2006, he was awarded the title of Honorary Conductor by three more orchestras: the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra as well as the Bamberger Symphoniker, which he has been conducting since 1982. In addition, he continues guest conducting the world's most pre-eminent orchestras. His extensive discography includes over 130 works with the Dresden Staatskapelle, amongst them all symphonies of L.v. Beethoven and Schubert. With the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra Herbert Blomstedt recorded the complete works of Carl Nielsen. 1987 he and the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra signed up an exclusive contract with Decca and numerous of their recordings received major awards; his complete cycles of the symphonies of Jean Sibelius and Carl Nielsen enjoy reference standard. |

HB: No. The

composers have mostly taken care of that problem themselves. A

very long symphony, like one of the longer Bruckner symphonies or a

Mahler symphony, is very carefully planned to be able to be digested in

one mouthful, so to speak, in one evening. The diversion, the

diversity, is built into the piece. There is enough change and

difference of moods within the same style to keep everyone very alert.

HB: No. The

composers have mostly taken care of that problem themselves. A

very long symphony, like one of the longer Bruckner symphonies or a

Mahler symphony, is very carefully planned to be able to be digested in

one mouthful, so to speak, in one evening. The diversion, the

diversity, is built into the piece. There is enough change and

difference of moods within the same style to keep everyone very alert. HB: One of the

nicest things in America today is the composer-in-residence program,

where a composer becomes attached to a symphony orchestra for a period

of time — two years, three, four years, any time

that is agreed upon — and during this time he

lives with the orchestra practically. He listens to the concerts,

gets impulses from the players, acts as advisor on the question of new

music for the repertoire for the orchestra, and perhaps most important,

writes pieces for the orchestra — at least one piece a year that is

then performed by the orchestra. He knows that he has some secure

performances, and even takes them on tour abroad. It’s a large

commitment that the orchestra makes that should stimulate the composer

very much. Then the composer, on the other hand, influences the

players and the conductor. He should be full of the concerns of

the modern situation, the actual situation for composers today.

HB: One of the

nicest things in America today is the composer-in-residence program,

where a composer becomes attached to a symphony orchestra for a period

of time — two years, three, four years, any time

that is agreed upon — and during this time he

lives with the orchestra practically. He listens to the concerts,

gets impulses from the players, acts as advisor on the question of new

music for the repertoire for the orchestra, and perhaps most important,

writes pieces for the orchestra — at least one piece a year that is

then performed by the orchestra. He knows that he has some secure

performances, and even takes them on tour abroad. It’s a large

commitment that the orchestra makes that should stimulate the composer

very much. Then the composer, on the other hand, influences the

players and the conductor. He should be full of the concerns of

the modern situation, the actual situation for composers today. HB: No, where it

should go. It is the general frame of laying down tempos,

balances, phrasings, articulations, and so on, and then at the concert,

small but very important variations of this is taking place all the

time. Not a single concert is the same. If you repeat the

program four times, as we do regularly in Chicago, no two performances

will be alike.

HB: No, where it

should go. It is the general frame of laying down tempos,

balances, phrasings, articulations, and so on, and then at the concert,

small but very important variations of this is taking place all the

time. Not a single concert is the same. If you repeat the

program four times, as we do regularly in Chicago, no two performances

will be alike. BD: I assume that

the baton technique is the least of your worries.

BD: I assume that

the baton technique is the least of your worries. HB: Perhaps you

could say that. But I think some of them got to love music as a

result of this. What was the device of the Roman Emperors? “Give

the people bread and circuses and they will not revolt.”

The Saxonian kings cared for their people, gave them jobs and bread and

defended their borders, but they also gave them entertainment of a high

order. Especially for their visitors who wanted to see their

splendor, they put on the very best. It’s like a parade of the

greatest names when you look at the history of the orchestra.

Their first music director was Johann Walter, who was the musical

collaborator of Luther. The first German opera was written by

Heinrich Schütz, who is mostly known as a composer for the church

a hundred years before Bach. He was in charge of the various Staatskapelle for over fifty

years. Of course, at that time the orchestra was not a symphony

orchestra; it was a royal chapel of players and singers, at times very

small. That was the time of the Thirty Years War. Sometimes

the glorious opera orchestra would go down to just a few members, a few

singers and players, but it was continuous, and that is why the Dresden

Staatskapelle has a long history. It was continuous all the time.

HB: Perhaps you

could say that. But I think some of them got to love music as a

result of this. What was the device of the Roman Emperors? “Give

the people bread and circuses and they will not revolt.”

The Saxonian kings cared for their people, gave them jobs and bread and

defended their borders, but they also gave them entertainment of a high

order. Especially for their visitors who wanted to see their

splendor, they put on the very best. It’s like a parade of the

greatest names when you look at the history of the orchestra.

Their first music director was Johann Walter, who was the musical

collaborator of Luther. The first German opera was written by

Heinrich Schütz, who is mostly known as a composer for the church

a hundred years before Bach. He was in charge of the various Staatskapelle for over fifty

years. Of course, at that time the orchestra was not a symphony

orchestra; it was a royal chapel of players and singers, at times very

small. That was the time of the Thirty Years War. Sometimes

the glorious opera orchestra would go down to just a few members, a few

singers and players, but it was continuous, and that is why the Dresden

Staatskapelle has a long history. It was continuous all the time. BD: Is the

temptation great to give more and more concerts, and overwork the

orchestra?

BD: Is the

temptation great to give more and more concerts, and overwork the

orchestra? HB: [Laughs]

Well, every orchestra is so different. Everybody knows that the

Chicago Symphony is a great orchestra, and I love the orchestra, but

it’s not the Dresden Orchestra, neither is the Dresden Orchestra the

Chicago Symphony. Also the San Francisco Symphony is a wonderful

symphony, but it’s not the Chicago Symphony.

HB: [Laughs]

Well, every orchestra is so different. Everybody knows that the

Chicago Symphony is a great orchestra, and I love the orchestra, but

it’s not the Dresden Orchestra, neither is the Dresden Orchestra the

Chicago Symphony. Also the San Francisco Symphony is a wonderful

symphony, but it’s not the Chicago Symphony. HB: If you want a

yes or no, I cannot answer the question! [Both laugh]

Conducting gives me immense joy for many reasons. First of all, I

can deal with the greatest music. Some of the greatest music is

written for the orchestra. A great deal of the greatest music is

written for orchestra. There’s lot of wonderful music written for

string quartets, for the piano, as we all know, but some of the

greatest composers have reserved their greatest efforts for the

orchestra. I think that’s undisputed. That’s a great

privilege. Then there is the joy of dealing with absolute

masterworks and dealing with orchestras that are so refined and so

wonderfully equipped with wonderful musicians — as

for instance the Chicago Symphony. It puts its stamp on every

musician that is associated with this kind of music and with this kind

of musician. How can you devote your life to studying Beethoven

symphonies or Bruckner symphonies without being a little bit colored by

the object of your love? I’m not saying that we are perfect and

that we are any way saints, but I cannot imagine what our life would be

without it. It has put its stamp on our values, on our sense of

beauty, and we are so much richer with it. For the conductor

especially there is special satisfaction of being, in a very special

way, in the midst of all this music-making. We get to look into

the eyes of a hundred musicians who all love the same music we are

doing with the same fervor, and have only one desire which is to make

as a rich and fully experienced and perfect a performance as

possible. These are musicians who are willing at any moment to

sacrifice his or her own vanity — which we all have — for the sake of a

neighbor who happens to have a solo right now, and to wait for your

opportunity a couple of bars later when it’s your turn, not only

because the conductor demands it but because the music demands

it. To see the musicians experience this and who are willing to

subdue personal likes or dislikes for a moment for the common value, to

see how this is done with absolute conviction and abandon is a

wonderful experience! I feel always very attached to my

musicians. Making music with them is like touching their most

holy parts. How could it be otherwise? The emotional

contact is so intense that it’s unforgettable. That’s why I

cannot forget a musician that I have played with. It’s like being

married to this person when we have made music together, and that is a

very special joy. But all this, of course, also has its

hardships. It’s enormous hard work. You have to sacrifice

many other things, perhaps things that you also love to do, such as

being able to devote more time for hobbies, or above all, for your

family. You have to concentrate on one thing, then arrange a set

of priorities in a way that is sometimes painful for yourself and also

for your family and others. So it’s not a dance on roses.

You also have to cope with failure. After all, a hundred

musicians can make a hundred more mistakes than one musician. The

apparatus is so complicated! It takes lots of skill and some luck

to make it work, and as time goes on we get more and more sensitive to

the mishaps that happen. Our standards become very high. I

don’t mean that in a haughty way at all; we just simply notice more

mistakes the more experience we get. We have to cope with

that. It’s really terrible to have the feeling after every

concert that this was not so good, this was not so good, this was not

so good, this could have been better. If that dominates our

feeling, conducting is a nightmare.

HB: If you want a

yes or no, I cannot answer the question! [Both laugh]

Conducting gives me immense joy for many reasons. First of all, I

can deal with the greatest music. Some of the greatest music is

written for the orchestra. A great deal of the greatest music is

written for orchestra. There’s lot of wonderful music written for

string quartets, for the piano, as we all know, but some of the

greatest composers have reserved their greatest efforts for the

orchestra. I think that’s undisputed. That’s a great

privilege. Then there is the joy of dealing with absolute

masterworks and dealing with orchestras that are so refined and so

wonderfully equipped with wonderful musicians — as

for instance the Chicago Symphony. It puts its stamp on every

musician that is associated with this kind of music and with this kind

of musician. How can you devote your life to studying Beethoven

symphonies or Bruckner symphonies without being a little bit colored by

the object of your love? I’m not saying that we are perfect and

that we are any way saints, but I cannot imagine what our life would be

without it. It has put its stamp on our values, on our sense of

beauty, and we are so much richer with it. For the conductor

especially there is special satisfaction of being, in a very special

way, in the midst of all this music-making. We get to look into

the eyes of a hundred musicians who all love the same music we are

doing with the same fervor, and have only one desire which is to make

as a rich and fully experienced and perfect a performance as

possible. These are musicians who are willing at any moment to

sacrifice his or her own vanity — which we all have — for the sake of a

neighbor who happens to have a solo right now, and to wait for your

opportunity a couple of bars later when it’s your turn, not only

because the conductor demands it but because the music demands

it. To see the musicians experience this and who are willing to

subdue personal likes or dislikes for a moment for the common value, to

see how this is done with absolute conviction and abandon is a

wonderful experience! I feel always very attached to my

musicians. Making music with them is like touching their most

holy parts. How could it be otherwise? The emotional

contact is so intense that it’s unforgettable. That’s why I

cannot forget a musician that I have played with. It’s like being

married to this person when we have made music together, and that is a

very special joy. But all this, of course, also has its

hardships. It’s enormous hard work. You have to sacrifice

many other things, perhaps things that you also love to do, such as

being able to devote more time for hobbies, or above all, for your

family. You have to concentrate on one thing, then arrange a set

of priorities in a way that is sometimes painful for yourself and also

for your family and others. So it’s not a dance on roses.

You also have to cope with failure. After all, a hundred

musicians can make a hundred more mistakes than one musician. The

apparatus is so complicated! It takes lots of skill and some luck

to make it work, and as time goes on we get more and more sensitive to

the mishaps that happen. Our standards become very high. I

don’t mean that in a haughty way at all; we just simply notice more

mistakes the more experience we get. We have to cope with

that. It’s really terrible to have the feeling after every

concert that this was not so good, this was not so good, this was not

so good, this could have been better. If that dominates our

feeling, conducting is a nightmare.

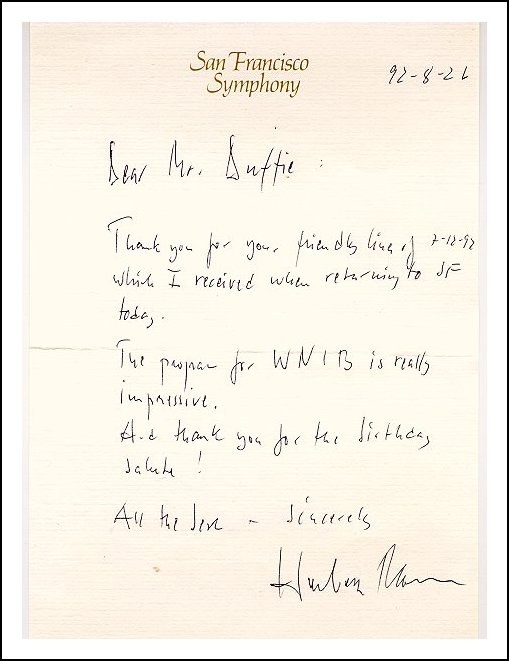

This interview was recorded backstage at Orchestra

Hall in Chicago on January 8, 1988. Sections

were used (along with

recordings) on WNIB in 1990, 1992 and 1997.

It was transcribed

and posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.