BD: You've sung both

the Don and Leporello?

BD: You've sung both

the Don and Leporello?|

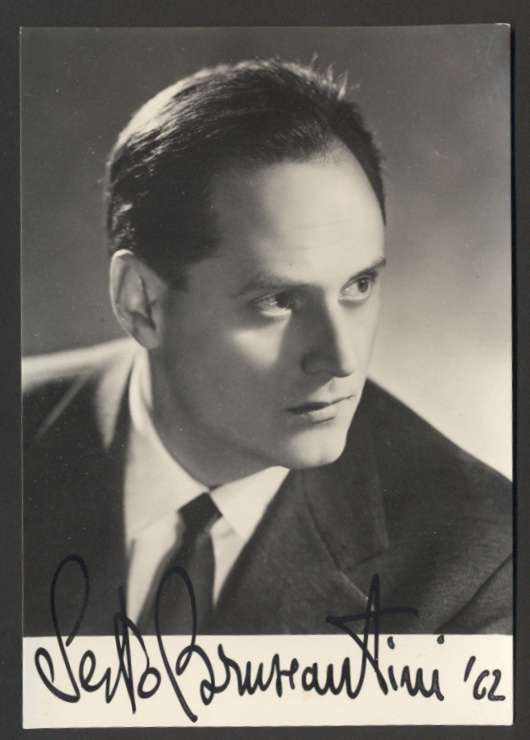

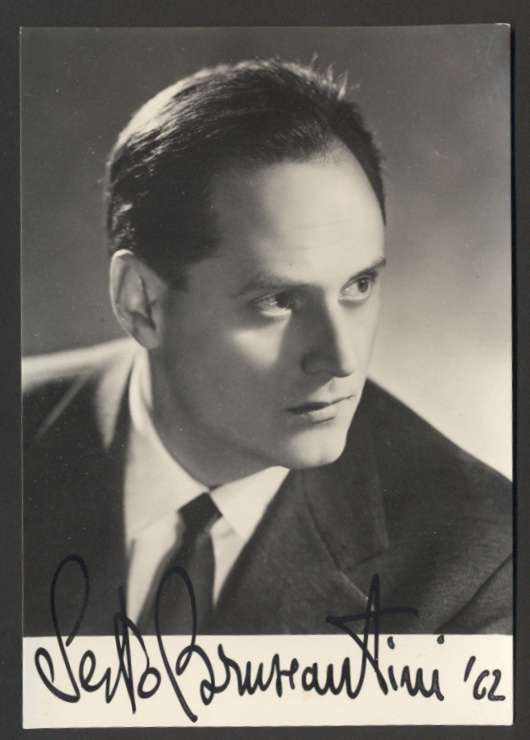

Sesto Bruscantini at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1961 - Figaro (Barber of Seville) [American Debut] 1963 - Malatesta (Don Pasquale) 1964 - Alfonso XI (La Favorita), Marcello (La Bohème), Dandini (La Cenerentola) 1965 - Marcello (La Bohème), Sharpless (Madama Butterfly), High Priest (Samson), Baritone (Carmina Burana), Ramiro (L'Heure Espagnol), Rigoletto (Rigoletto) 1966 - Zurga (Pearl Fishers), Germont (Traviata) 1968 - Malatesta (Don Pasquale) 1969 - Figaro (Barber of Seville) 1981 - Father Laurence (Romeo and Juliette) 1982 - Sharpless (Madama Butterfly) 1984 - Bartolo (Barber of Seville) 1985-86 - Sharpless (Madama Butterfly) |

Sesto Bruscantini

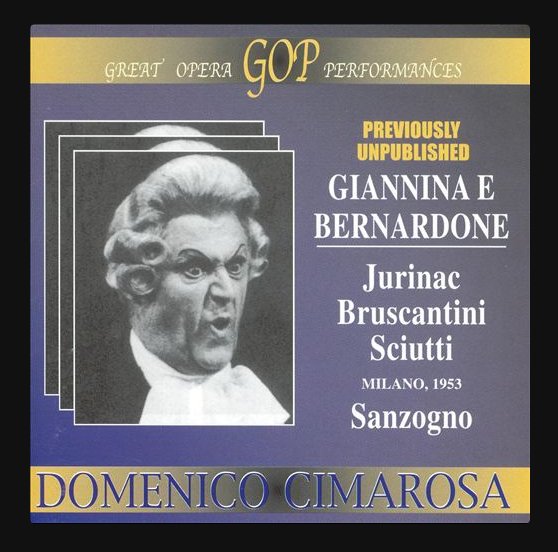

Sympathetic bass-baritone with a long career and an enormous repertory By Elizabeth Forbes, The Independent, 12 May 2003 During a career that lasted 45 years, the Italian bass-baritone Sesto Bruscantini acquired an enormous repertory that was notable for the range, musical and dramatic, of the roles that he sang, as well as for their number. At first a bass, specialising in the comic roles of Mozart, Rossini and Donizetti, he moved up the scale to baritone and even, for some years in the middle of his career, took on the high Verdi baritone roles. His voice was not huge, but so well projected that no strain showed, however florid or heavy the vocal line. But it was his skill in characterisation that enabled Bruscantini to sing so many roles in such different styles. He had a tremendous success at Glyndebourne in the 1950s, and at the Chicago Lyric during the 1960s, and sang at La Scala, Milan, the Rome Opera and many other Italian cities throughout his career. Sesto Bruscantini was born at Civitanova Marche in the Marche, in 1919. His father was a lawyer and Sesto also studied law, graduating from Macerata University in 1944. He had already won a singing competition at Florence, and in 1945 studied for a year in Rome with Luigi Ricci. To pay for his studies he wrote comments in verse on topical news for a weekly paper. After making his professional début in 1946 at Civitanova as Colline in La bohème, he spent a year at the Rome Opera School, singing small roles such as the Notary in Gianni Schicchi, and the First Nazarene in Salome. He also sang in many concerts and began a fruitful relationship with Italian Radio as Sulpice in Donizetti's La Fille du régiment. Bruscantini first sang at La Scala in 1949, as Don Geronimo in Cimarosa's Il matrimonio segreto, a role that would remain in his repertory for many years. In 1950 he sang Selim in Rossini's Il turco in Italia in Rome, with a stellar cast including Maria Callas, Cesare Valletti and Mariano Stabile. The following year he returned to La Scala for Dr Dulcamara in Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore, another role he would still be singing some 40 years later. He also sang Masetto in Don Giovanni. Nineteen fifty-one was the 50th anniversary of Verdi's death, and Bruscantini sang Baron Kelbar in Un giorno di regno for Radio Italiana. At Glyndebourne that summer of 1951 he made his début as Don Alfonso in Così fan tutte. Singing Fiordiligi was the Yugoslav soprano Sena Jurinac. The following year he moved to Guglielmo in Così fan tutte and also scored a huge success as Dandini in Rossini's La Cenerentola, both of which were quite definitely baritone roles. After leaving Glyndebourne he went straight to Salzburg, where he sang the title role of Donizetti's Don Pasquale. Later that year he sang his first Mozart Figaro in Le nozze di Figaro for Netherlands Opera. Early in 1953 he returned to La Scala for Leporello in Don Giovanni and Tadeo in Rossini's L'italiana in Algerì. Back at Glyndebourne that summer he repeated his wonderfully comic and elegant Dandini, and returned to Don Alfonso. In June he and Sena Jurinac were married in Lewes, appearing in Così fan tutte the same evening. They also sang together in the prologue to Ariadne auf Naxos by Richard Strauss, with Jurinac as the Composer and Bruscantini as the Music Master, an unusual excursion into German opera – he sang Papageno in The Magic Flute, but only in Italian. His marriage to Jurinac was at first a great success, but later they grew apart and the marriage was dissolved – with great difficulty on Bruscantini's side. In the summer of 1954 he sang Rossini's Figaro in Il barbiere di Siviglia at Glyndebourne, and with the company in Edinburgh took on Raimbaud in Rossini's Le Comte Ory. Meanwhile he was appearing in Genoa, Venice, Naples, Rome, Bologna and Lisbon. At Glyndebourne in 1955 he sang both Mozart's and Rossini's Figaro, demonstrating his ability to bring a character to vibrant life. He felt that the mainspring of Rossini's Figaro was money and that of Mozart's was love; a third Figaro, in Paisiello's Il barbiere, which was also in his repertory, was the only one motivated, like the Beaumarchais original, by revolutionary politics. Bruscantini gained another baritone role in Malatesta in Don Pasquale at Genoa in 1958, but early the following year reverted to Pasquale at La Scala. In 1959 he appeared at the Royal Festival Hall in London with the Virtuosi di Roma in three 18th-century comic operas, as Uberto in Pergolesi's La serva padrona, as Don Bucefalo in Fioravanti's Le cantatrici villane and in the title role of Il maestro di cappella by Cimarosa, a one-man show that peopled the stage with imaginary characters and always brought the house down. Nineteen-sixty was a milestone in Bruscantini's career. In February and March he sang the four baritone villains in Les Contes d'Hoffmann and Marcello in La bohème at the San Carlo, Naples. Then at Glyndebourne in the summer he took on his first Verdi baritone role, Ford in Falstaff. He repeated Ford at Edinburgh and in Turin, then in November [of 1961] he made his US début in Chicago as Rossini's Figaro. In 1962 he sang his first Posa in Verdi's Don Carlos at Trieste. Other high baritone roles followed, and in 1965 another new Verdi role, Renato in Un ballo in maschera, at Florence. This was followed by Giorgio Germont in La traviata at Genoa in 1966. The elder Germont was perhaps Bruscantini's finest baritone characterisation. He sang it in Madrid, Chicago, Palermo and Parma, during the 1960s, and at Marseilles in 1971, with Renata Scotto as Violetta. The depth of feeling he brought to the role was unique in my experience, and he evoked enormous sympathy for a personage who is often taken to be unsympathetic. Bruscantini made a very belated Covent Garden début in 1971 as Rossini's Figaro. He returned to London in 1974 as Malatesta in Don Pasquale, which was very well received. In 1976 his fine rendering of Simon Boccanegra in the original, 1857 version of Verdi's opera was broadcast by the BBC on New Year's Day, and the following month he sang his first Falstaff with Scottish Opera in Glasgow. Though he made the fat knight a lonely, rather sad old man, he lit the performance with many sly touches of humour. In 1977 Bruscantini made the first of three visits to the Wexford Festival, during which he directed the operas as well as singing in them. A triple bill of Il maestro di cappella, La serva padrona and Ricci's La serva e l'ussero was followed in 1979 by Crispino e la comare by the Ricci brothers, and in 1981 by Verdi's Un giorno di regno, in which Bruscantini sang Baron Kelbar, exactly 30 years after singing the role for Radio Italiana. In 1980 the 60-year-old Bruscantini made his début at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, as Taddeo in L'italiana, followed by Dr Dulcamara in L'elisir d'amore. He continued to sing throughout the 1980s, appearing at Salzburg three years running as Don Alfonso in Così fan tutte. At Houston he took on Dr Bartolo in Il barbiere. He returned to Glyndebourne in 1985 as Don Magnifico. In 1986 he sang Iago (never one of his best roles) at Dallas in an emergency and obtained a new Rossini role at Bordeaux, Asdrubale in La pietra del paragone. In 1988 he sang Don Alfonso in Los Angeles, the four villains in Madrid. In 1989 he sang Michonnet in Rome. In 1990, also in Rome, he sang a new role, the Magistrate in Werther, and sang a final Don Alfonso in Macerata. He was 70. After retiring from the opera stage, he started a school of singing in Civitanova. Sesto Bruscantini, opera singer, director and teacher: born Civitanova Marche, Italy 10 December 1919; married first 1953 Sena Jurinac (marriage dissolved), second Angela Pallota; died Civitanova Marche 4 May 2003. |

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at his apartment in Chicago on

December 9, 1981. The translation was provided by Marina Vecci of

Lyric Opera of Chicago. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB in 1989, 1994, and 1999. The

transcription was made and published in Opera Scene in December,

1982. It was re-editied, photos, bios and links were added, and

it was posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.