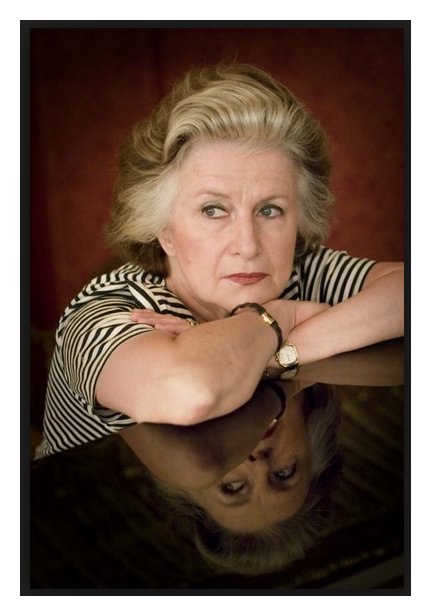

| Joanna Bruzdowicz comes from a

musical family: her father was an architect and cellist, her mother a

pianist. Bruzdowicz started her musical career as a child prodigy when

she began to compose at the age of six. Interestingly, she later

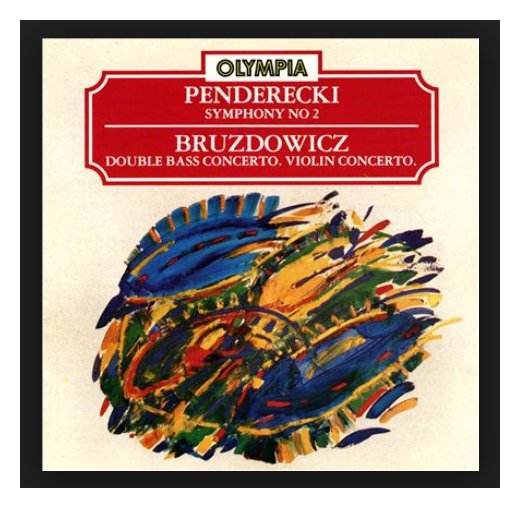

dedicated much of her efforts to promoting music for the youth. She studied at the Warsaw Music High School, at the State Higher School of Music (composition with Kazimierz Sikorski and piano with Irena Protasewicz and Wanda Łosakiewicz); she earned her M.A. in 1966. She traveled to Paris to continue her studies on a scholarship from the French government and became a student of Nadia Boulanger, Oliver Messiaen and Pierre Schaeffer (1968-70). While in Paris, she joined the electro acoustic Groupe de Recherches Musicales and wrote her doctoral thesis Mathematics and Logic in Contemporary Music at the Sorbonne. After completing her studies in France, she settled in Belgium and established herself as a composer there. She recently moved to southern France. Bruzdowicz was amongst the Polish female students of the most famous teacher of composition in the 20th century, Nadia Boulanger. The group also included Grażyna Bacewicz, Anna Maria Klechniowska, Bernardetta Matuszczak, Barbara Niewiadomska, and Marta Ptaszyńska. Boulanger's advice was very firm and non-compromising: she insisted that composers have no right to self-pity or self-indulgence, but solely the right to work, work, work. This principle was internalized by her most talented students, such as Bacewicz, Bruzdowicz or Ptaszyńska, and expressed in their intensely focused work habits that resulted in the high volume and quality of their output. As a composer she devoted her attention to opera, symphonic and chamber music, works for children, and music for film and television. She wrote four concerti and numerous chamber pieces, as well as over 25 hours of film music. Her compositions are featured on 12 CDs and over 20 LPs; she has been featured in TV programs produced in Belgium, France, Germany and Poland. Bruzdowicz's music has been praised for its "poetic palette of sound" and its qualities of being "ultramodern and refined" while remaining expressive and personal. Her output includes several operas which brought to the stage some of the greatest works of European literature (e.g. The Penal Colony, after Kafka, 1972; The Women of Troy after Euripides, 1973; and The Gates of Paradise, after Jerzy Andrzejewski, 1987). Bruzdowicz was the only Polish composer and the only woman selected to the final round of 12 composers who were invited to create a new Hymn for the Vatican (a French composer won). Her Stabat Mater written in 1993 for a special ceremony held at Forest Lawn Memorial in Glendale, California (unveiling in a restored theatre Jan Styka's monumental panorama of the Crucifixion, commissioned by Paderewski) was attended by the representatives of the city and county, and the Polish government, among over one thousand guests. This choral work is dedicated to PMC founder Wanda Wilk. In 2001 Bruzdowicz received the highest distinction from the Polish government—the Order of Polonia Restituta—for her contributions to Polish culture. Promoting Polish music is her passion and she has produced hours of radio programs devoted to this subject for radio stations in France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain and the U.S. She is a co-founder of various musical organizations: Chopin-Szymanowski Association in Belgium, Jeunesses Musicales in Poland, GIMEP in France, and International Encounters in Music in Catalonia. Thanks to her efforts, numerous Polish composers received their first performances in Europe and the U.S. One of her most notable projects was a special concert held in December 1985 during the Year of European Music; the concert was devoted to the "forgotten Europe," that is its Eastern part. The Belgium Radio Orchestra performed works by Szymanowski, Shostakovich, Dvořák and Bartók. A live recording from this concert was reviewed across Europe. Active as a founder and board member of the Polish section of Jeunesses Musicales, she is also founder and President of the Frederic Chopin and Karol Szymanowski Society of Belgium, and Vice-President of the International Federation of Chopin Societies. Joanna Bruzdowicz was the second composer to offer her manuscripts to our collection; she was preceded in this sign of generosity only by Witold Lutosławski. The manuscripts of her works were included in the Manuscript Exhibition held at the PMC in October 2000. -- Biography from the

Polish Music Center of USC website

|

JB: Yes, in

everything. It’s one of the most

beautiful cities. It’s a wonderful city. It’s a mixture of

everything. It’s

a mixture of people of many, many origins. Not just that I

am very proud to be from central Europe, but I think it’s a central

European culture dominating Chicago, with a lot of Polish, German,

Italian, and many others bringing a whole culture for everybody.

This

mixture shows the interest for culture coming from this part of

Europe to be involved in art and

music atmosphere.

JB: Yes, in

everything. It’s one of the most

beautiful cities. It’s a wonderful city. It’s a mixture of

everything. It’s

a mixture of people of many, many origins. Not just that I

am very proud to be from central Europe, but I think it’s a central

European culture dominating Chicago, with a lot of Polish, German,

Italian, and many others bringing a whole culture for everybody.

This

mixture shows the interest for culture coming from this part of

Europe to be involved in art and

music atmosphere. JB: It’s my form of

four seasons. The

exact name of this piece is Four

Seasons Greetings. It’s my

salutation to the United States, at the same time it’s season’s

greetings, and it was a kind of dedication for United

States. Every season has a title and another

soloist. The chamber orchestra is exactly the same number

of musicians as in the Vivaldi Four

Seasons. For spring, called Bridges of

Venice, we have two solo violins; for summer,

called Western Ballad and

dedicated to United States completely, we

have piano four hands; the autumn is Tropic

of Capricorn, and because

the Tropic of Capricorn is going across Brazil it’s like a samba for

flute and chamber orchestra; and the fourth part, winter, is

called Indian Trail, and was

played the first time by a

very good, very famous marimba player from Canada, and its part is

dedicated to her and to Canada. So it’s very snowy and very

cold. [Both laugh]

JB: It’s my form of

four seasons. The

exact name of this piece is Four

Seasons Greetings. It’s my

salutation to the United States, at the same time it’s season’s

greetings, and it was a kind of dedication for United

States. Every season has a title and another

soloist. The chamber orchestra is exactly the same number

of musicians as in the Vivaldi Four

Seasons. For spring, called Bridges of

Venice, we have two solo violins; for summer,

called Western Ballad and

dedicated to United States completely, we

have piano four hands; the autumn is Tropic

of Capricorn, and because

the Tropic of Capricorn is going across Brazil it’s like a samba for

flute and chamber orchestra; and the fourth part, winter, is

called Indian Trail, and was

played the first time by a

very good, very famous marimba player from Canada, and its part is

dedicated to her and to Canada. So it’s very snowy and very

cold. [Both laugh] JB: Yes, and I’m

using several saxophones in my

film music all the time. I have wonderful musicians to play

saxophone in Poland. They are really wonderful jazz men, and also

classical musicians. So I dream to find the time and to write a

concerto for one of them, but even without commission I’d like

to do it. I have no time now. The most important

works for me always are the operas.

JB: Yes, and I’m

using several saxophones in my

film music all the time. I have wonderful musicians to play

saxophone in Poland. They are really wonderful jazz men, and also

classical musicians. So I dream to find the time and to write a

concerto for one of them, but even without commission I’d like

to do it. I have no time now. The most important

works for me always are the operas. JB: Not too

often. Once I was obliged to do it with my First String Quartet because Agnes

Varda, the French film director, wanted this quartet as music for her

Vagabond film. It was a

very famous film winning the prize of the Los Angeles Film Critics as

the best foreign

film. It also won the Golden Lion in Venice. Varda had 35

or 36 records with string chamber music from 20th century,

and she found my string quartet. So she asked me to write fifteen

minutes of variations because she made a choice of many fragments of

this

record. But she wanted more music for special places in her

film, so I was obliged to return to my string quartet and to

write it. I was not happy because I hate to return to something

which is finished. I am so happy

to finish a work and to close the score and just pass it along and have

it performed.

JB: Not too

often. Once I was obliged to do it with my First String Quartet because Agnes

Varda, the French film director, wanted this quartet as music for her

Vagabond film. It was a

very famous film winning the prize of the Los Angeles Film Critics as

the best foreign

film. It also won the Golden Lion in Venice. Varda had 35

or 36 records with string chamber music from 20th century,

and she found my string quartet. So she asked me to write fifteen

minutes of variations because she made a choice of many fragments of

this

record. But she wanted more music for special places in her

film, so I was obliged to return to my string quartet and to

write it. I was not happy because I hate to return to something

which is finished. I am so happy

to finish a work and to close the score and just pass it along and have

it performed.© 1991 Bruce Duffie

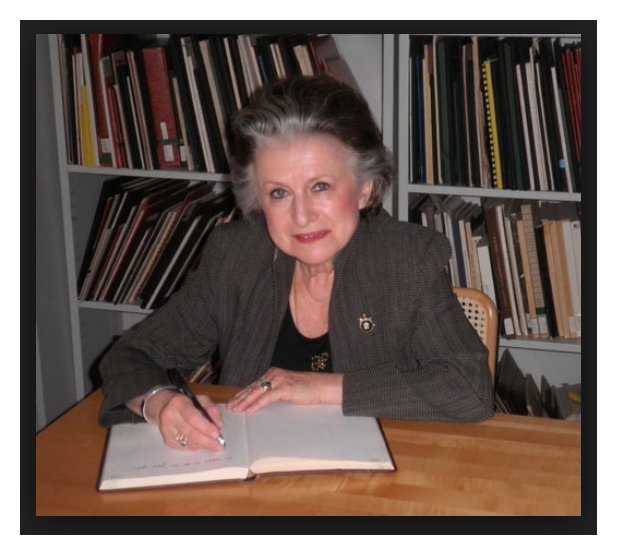

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 7, 1991.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993 and 1998.

This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.