RC: Basically, I

devote three-quarters of the season to the symphonic activity,

especially

in Amsterdam with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, and a quarter to the

Bologna Teatro Communale activity, for an opera production each

year. But I would say it’s something

which I like to do; I certainly do not regret to balance it that

way. After my American debut in

’74, I came back in ’76, ’78, and ’79 and in that time I was

conducting basically opera during the season. Although I am

Italian and it’s something I love and I would never leave, still I felt

it was time to balance it differently. Now the activity with the

Concertgebouw

Orchestra causes me to reduce categorically opera, and in this

respect I’m pretty pleased, so far.

RC: Basically, I

devote three-quarters of the season to the symphonic activity,

especially

in Amsterdam with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, and a quarter to the

Bologna Teatro Communale activity, for an opera production each

year. But I would say it’s something

which I like to do; I certainly do not regret to balance it that

way. After my American debut in

’74, I came back in ’76, ’78, and ’79 and in that time I was

conducting basically opera during the season. Although I am

Italian and it’s something I love and I would never leave, still I felt

it was time to balance it differently. Now the activity with the

Concertgebouw

Orchestra causes me to reduce categorically opera, and in this

respect I’m pretty pleased, so far. BD: Do you feel that

when you conduct a Mahler

symphony, you are in competition with the memory of Haitink or the

other previous conductors? [See my Interview with Bernard

Haitink.]

BD: Do you feel that

when you conduct a Mahler

symphony, you are in competition with the memory of Haitink or the

other previous conductors? [See my Interview with Bernard

Haitink.]  RC: I try to

reproduce the same intention in terms of

emotion and deep conviction of an interpretation. But I generally

try to

get more precision than in a live performance; more

precision in terms of performance itself, and also more precision in

terms of details. I’m a little bit maniacal in that respect, and

my recording company knows that very well, having been with them

exclusively for over ten years. And I think sometimes the beauty

of digital

sound is even a stronger temptation to go more and more into those

things, to be able to reproduce something that even the

concert is not able to. For instance, we might be able to pick up

small

details in the orchestration which sometimes, due to acoustical

reasons, you cannot pick up from the hall just by listening to a

concert. And the major difficulty, I think, is probably not only

that,

but the reproduction of emotions. That

sometimes is very difficult. I am not, as everybody else is now,

in

favor of live recordings. On the contrary, I am in favor of

studio

recordings, but in that respect, I know how difficult it is to

reproduce the degree of emotion compared the concert the night

before. When it happens — and it does

happen, indeed, thank God — it’s even more

intimate. Then the intimacy between conductor and

orchestra is even stronger, and the degree of interpretation of

emotion can be even higher if reproduced between the two of

you. It’s even more meaningful, somehow, and if the

microphone is there in that moment, then that really is the magic

moment.

RC: I try to

reproduce the same intention in terms of

emotion and deep conviction of an interpretation. But I generally

try to

get more precision than in a live performance; more

precision in terms of performance itself, and also more precision in

terms of details. I’m a little bit maniacal in that respect, and

my recording company knows that very well, having been with them

exclusively for over ten years. And I think sometimes the beauty

of digital

sound is even a stronger temptation to go more and more into those

things, to be able to reproduce something that even the

concert is not able to. For instance, we might be able to pick up

small

details in the orchestration which sometimes, due to acoustical

reasons, you cannot pick up from the hall just by listening to a

concert. And the major difficulty, I think, is probably not only

that,

but the reproduction of emotions. That

sometimes is very difficult. I am not, as everybody else is now,

in

favor of live recordings. On the contrary, I am in favor of

studio

recordings, but in that respect, I know how difficult it is to

reproduce the degree of emotion compared the concert the night

before. When it happens — and it does

happen, indeed, thank God — it’s even more

intimate. Then the intimacy between conductor and

orchestra is even stronger, and the degree of interpretation of

emotion can be even higher if reproduced between the two of

you. It’s even more meaningful, somehow, and if the

microphone is there in that moment, then that really is the magic

moment. BD: So then you’re

always trying to touch the soul of

the audience?

BD: So then you’re

always trying to touch the soul of

the audience? RC: Unfortunately,

yes, especially more and more in these days. And

I think this is a fashion which has to stop, because it could be the

death of opera, I believe, if the producer has more and more to say,

even more than the conductor, about opera, about staging, about how to

take over an interpretation. The major secret, I think, is really

to have a meeting and discussion between the conductor and producer

— much before the

production itself starts to exist — and just try

to talk

about the piece and exchange opinions

about it. That very often happens and very

seldom he maintains the promise. [Laughter] The meeting is

fantastic. You have a

wonderful understanding! One and a half years before it opens I

make my ideas clear. I

make sure I won’t interfere with this; I make sure I won’t interfere

with that. Then at the end, a big conflict starts. This is

really happening so damn often these days, and I think that’s a

great pity. My background is Italian and I am an opera animal, so

one of the

secrets why I am so happy to be Chief Conductor in Bologna is that we

have a way of

doing opera there which is absolutely against this horrible trend of

self-destructive feelings in terms of productions

and producers against conductors, and vice versa. It is

not a dictatorship on my part; it is really a

team working together and going ahead in the same direction. We are

really trying to not

only talk about each other’s idea, but to visualize the

production. After that first meeting a year and a half before the

scheduled opening date, we meet again six months later, going

back together with designs, with

the designer himself, and the costumes and so on, and try to really

conceive the whole thing together. This is a privilege which I

have in Bologna.

RC: Unfortunately,

yes, especially more and more in these days. And

I think this is a fashion which has to stop, because it could be the

death of opera, I believe, if the producer has more and more to say,

even more than the conductor, about opera, about staging, about how to

take over an interpretation. The major secret, I think, is really

to have a meeting and discussion between the conductor and producer

— much before the

production itself starts to exist — and just try

to talk

about the piece and exchange opinions

about it. That very often happens and very

seldom he maintains the promise. [Laughter] The meeting is

fantastic. You have a

wonderful understanding! One and a half years before it opens I

make my ideas clear. I

make sure I won’t interfere with this; I make sure I won’t interfere

with that. Then at the end, a big conflict starts. This is

really happening so damn often these days, and I think that’s a

great pity. My background is Italian and I am an opera animal, so

one of the

secrets why I am so happy to be Chief Conductor in Bologna is that we

have a way of

doing opera there which is absolutely against this horrible trend of

self-destructive feelings in terms of productions

and producers against conductors, and vice versa. It is

not a dictatorship on my part; it is really a

team working together and going ahead in the same direction. We are

really trying to not

only talk about each other’s idea, but to visualize the

production. After that first meeting a year and a half before the

scheduled opening date, we meet again six months later, going

back together with designs, with

the designer himself, and the costumes and so on, and try to really

conceive the whole thing together. This is a privilege which I

have in Bologna.| In this photo (at left) released

by

Teatro alla Scala, Italian conductor Riccardo Chailly, left, and

Italian film director Franco Zeffirelli acknowledge the applause at the

end of Giuseppe Verdi's "Aida" for the opening season at La Scala

theater, in Milan, Italy, Thursday, Dec. 7, 2006. Zeffirelli's return

to La Scala after more than a dozen years created an unprecedented

buzz: tickets reserved for sale online for all eleven showings of

"Aida'' sold out in a record two hours. The glitz and attention

surrounding the Milan season opener underlines La Scala's return to the

center of the cultural scene, not only in Italy, after several years

marked by tensions over the landmark opera house's management. (AP

Photo/Marco Brescia/Teatro alla Scala) |

RC: Someone once

said that music-making will certainly bring us to silence. I

don’t remember who stated that; it was a very important musician,

though. So important, that at that time, maybe ten or fifteen

years

ago when I heard such a statement, I thought, “My God, he’s

right! What a scary sentence.” The music, avant-garde music

especially, there is only way to go if you do not change — to go to

silence. I really deeply don’t believe it, and my activity in

Amsterdam with

the Concertgebouw Orchestra proves it, because we bring from three to

four world premieres a year. I think this

is a very important point to continue. You have to try to bring

to performances new languages, new identities of compositions

and composers. Music is, as I said, an indefinite art,

and many, many ways have to be discovered to compose. At the

moment there is a new wave in Italy and also in

Holland, of a Neo-Romantic. I think it is also in the

States. This could be one of the ways of discovering new

lines, new ideas, for avant-garde music. But I also like the

middle avant-garde, like

Rudolph Escher, who is a

very well-known Dutch composer who died a few years ago from

cancer. I think he was a very, very important composer. I

really like to devote my time, as far as my schedule allows me, to

discover new

composers as well as look into the so-called middle-aged composers,

like Petrassi or Dallapiccola.

RC: Someone once

said that music-making will certainly bring us to silence. I

don’t remember who stated that; it was a very important musician,

though. So important, that at that time, maybe ten or fifteen

years

ago when I heard such a statement, I thought, “My God, he’s

right! What a scary sentence.” The music, avant-garde music

especially, there is only way to go if you do not change — to go to

silence. I really deeply don’t believe it, and my activity in

Amsterdam with

the Concertgebouw Orchestra proves it, because we bring from three to

four world premieres a year. I think this

is a very important point to continue. You have to try to bring

to performances new languages, new identities of compositions

and composers. Music is, as I said, an indefinite art,

and many, many ways have to be discovered to compose. At the

moment there is a new wave in Italy and also in

Holland, of a Neo-Romantic. I think it is also in the

States. This could be one of the ways of discovering new

lines, new ideas, for avant-garde music. But I also like the

middle avant-garde, like

Rudolph Escher, who is a

very well-known Dutch composer who died a few years ago from

cancer. I think he was a very, very important composer. I

really like to devote my time, as far as my schedule allows me, to

discover new

composers as well as look into the so-called middle-aged composers,

like Petrassi or Dallapiccola. RC:

Sometimes. It used to be fun for me

probably because I started so young. In a way it’s becoming less

and less fun and more and more serious business. Sometimes it is

still a very moving art. I would say that the fun part probably

is related more to my past years than the present. But if you

asked me in terms of satisfaction, in terms of sometimes feeling that I

reach the goal of an interpretation, that happens more often now,

particularly since I became Chief Conductor of the Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra. There is really a very special

relationship and a very special understanding in music terms.

RC:

Sometimes. It used to be fun for me

probably because I started so young. In a way it’s becoming less

and less fun and more and more serious business. Sometimes it is

still a very moving art. I would say that the fun part probably

is related more to my past years than the present. But if you

asked me in terms of satisfaction, in terms of sometimes feeling that I

reach the goal of an interpretation, that happens more often now,

particularly since I became Chief Conductor of the Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra. There is really a very special

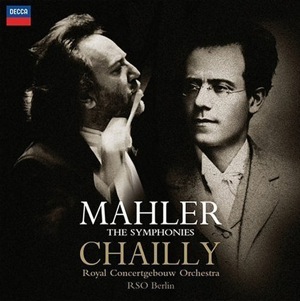

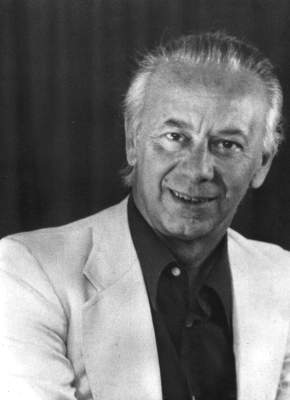

relationship and a very special understanding in music terms.Milan-born Riccardo Chailly

studied at the Conservatorio in Perugia,

Rome and Milan, specializing at the Siena summer courses with Franco

Ferrara. From 1982 to 1989, he was principal conductor of the Berlin

Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester, and from 1982 to 1985 principal guest

conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. From 1986 until 1993,

he led the Teatro Comunale of Bologna, where he conducted many greatly

successful opera productions. In 1986 he has been appointed chief

conductor and in 2002 conductor emeritus of the Royal Concertgebouw

Orchestra. From September 1999 to 2005 Riccardo Chailly was the Musical

Director of the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi. In

September 2005 Riccardo Chailly became chief conductor of the

Gewandhausorchester and music director of the Oper Leipzig. Riccardo Chailly is a conductor whose activities range

from the

symphonic to the operatic repertoire. He conducted the Berlin

Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic, the Leipzig Gewandhaus, the

London Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland

Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

and the Orchestre de Paris. He also performed at the world's most

famous opera houses, including La Scala in Milan (where he made his

debut in 1978), the Vienna State Opera, the Metropolitan Opera in New

York, the Royal Opera and Covent Garden in London (1979 debut), the

Bavarian State Opera in Munich and the Zürich Opera. In 1984,

Riccardo

Chailly opened the Salzburg Festival, where he also conducted the Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1988, 1996 and 1998. Has also conducted at

the city's Easter Festival. Riccardo Chailly is a conductor whose activities range

from the

symphonic to the operatic repertoire. He conducted the Berlin

Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic, the Leipzig Gewandhaus, the

London Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Cleveland

Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

and the Orchestre de Paris. He also performed at the world's most

famous opera houses, including La Scala in Milan (where he made his

debut in 1978), the Vienna State Opera, the Metropolitan Opera in New

York, the Royal Opera and Covent Garden in London (1979 debut), the

Bavarian State Opera in Munich and the Zürich Opera. In 1984,

Riccardo

Chailly opened the Salzburg Festival, where he also conducted the Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1988, 1996 and 1998. Has also conducted at

the city's Easter Festival.Riccardo Chailly led the Concertgebouw in numerous tours to the main European festivals (Salzburg, Lucerne, Vienna Festwochen, and London Proms) as well as to Japan, Korea, China, and North and South America. In 2001 he returned to conduct the Berliner Philharmoniker. In 2002 he led the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi in his first European tour, in France, Spain, Portugal and Switzerland, and in 2003 in Japan and Bruxelles, both with great success of critics and audience. In January 2004 he toured with the Orchestra to the Festival de Musica de Canarias. In May 2005 he led the Orchestra on a European tour to Croatia, Slovenia, Greece, Germany, Austria and Hungary. In 1994 Riccardo Chailly was entitled Grand'Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, and was made an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Music in London in 1996. During the 10th anniversary as chief conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in November 1998, he was knighted by Queen Beatrix, receiving the title of 'Knight in the Order of the Dutch Lion.' In Italy he was entitled, also in 1998, ‘Cavaliere di gran Croce della Repubblica Italiana’. In 2003 he received the “Antonio Feltrinelli” award by the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei of Rome, for his work as conductor in Italy. In November 2005 he was awarded his second Toblacher Komponierhauschen and the Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik by Germany. Riccardo Chailly has an exclusive contract with Decca. He has recorded a broad repertoire on CD which won many prizes, including Gramophone Awards, Diapasons d'Or, Edisons, the Academy Charles Cross Award, the Japanese Unga Knonotomo Award, the Toblacher Komponierhäuschen and several Grammy Nominations. Recently he was declared 'Artist of the year' by two important magazines, the French magazine Diapason and the British magazine Gramophone. With the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi he has recorded several CDs, including a new recording of orchestra transcriptions by Luciano Berio. September 2005 saw his first release as Kapellmeister of the Leipzig Gewandhaus with a live recording of his inaugural concert from the Gewandhaus itself featuring works by Mendelssohn. Future projects include Brahms Piano Concertos nos 1 & 2 with Nelson Freire in Spring 2006 and the Mendelssohn and Bruch Violin Concertos with Janine Jansen in Autumn 2006 – both are with the Leipzig GewandhausOrchester. Decca Records, November 2005

--

|

This interview was recorded at the Drake Hotel in Chicago on

September 28,

1990. Portions were used on WNIB

(along with musical examples) in 1993, 1998 and 1999. The

transcription was made in 2008 and posted on this

website in October of that year.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.