A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

DC: Sure, but I’m

not the one to be

pleased; he’s the one.

DC: Sure, but I’m

not the one to be

pleased; he’s the one. DC: Yes, in

general. In my opinion, the best sound of the recorded

concertos that I have done are the Haydn concertos. It was a

phenomenal recording studio, just a small dancehall in Vienna called

Casino Zogernitz. If you drove past this place, you wouldn’t

recognize anything about what it is. It used to be a dance hall,

but there’s millions of dollars of equipment in there now. The

sound

in that place was wonderful. Similarly, I like the sound on our

recording of Mahler

Eighth with Solti in the

Sofiensaal. But for the Haydn they had put the mikes in a very

good place

in front of me, and a reflective surface behind me. The sound was

as I imagine I would really like to sound if I were listening to myself

in a wonderful concert hall, which is possible only in my imagination.

DC: Yes, in

general. In my opinion, the best sound of the recorded

concertos that I have done are the Haydn concertos. It was a

phenomenal recording studio, just a small dancehall in Vienna called

Casino Zogernitz. If you drove past this place, you wouldn’t

recognize anything about what it is. It used to be a dance hall,

but there’s millions of dollars of equipment in there now. The

sound

in that place was wonderful. Similarly, I like the sound on our

recording of Mahler

Eighth with Solti in the

Sofiensaal. But for the Haydn they had put the mikes in a very

good place

in front of me, and a reflective surface behind me. The sound was

as I imagine I would really like to sound if I were listening to myself

in a wonderful concert hall, which is possible only in my imagination. BD: [Laughs]

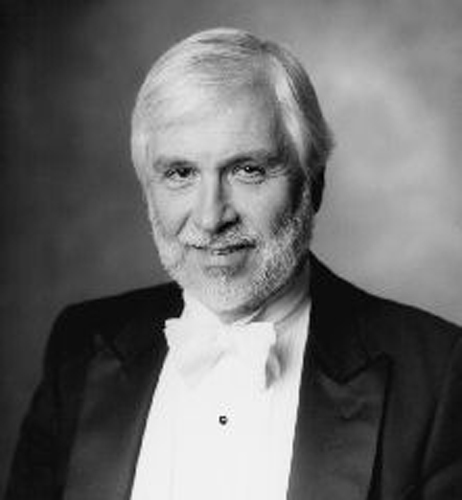

BD: [Laughs]| DALE CLEVENGER , principal horn of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since February 1966, is a versatile musician in many areas. He is a graduate of Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh. His mentors are Arnold Jacobs and Adolph Herseth. Before joining the Chicago Symphony, Mr. Clevenger was a member of Leopold Stokowski's American Symphony Orchestra and the Symphony of the Air, directed by Alfred Wallenstein, and was principal horn with the Kansas City Philharmonic. He has appeared as soloist with orchestras worldwide, including a recent solo engagement with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Daniel Barenboim, conductor. He has taken part in many music festivals: Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival, Florida Music Festival, Sarasota, Marrowstone Music Festival, Port Townsend, Washington, and Affinis Music Festival, Japan. His conducting career has included guest appearances with the New Japan Philharmonic, Tokyo, the Louisiana Philharmonic, the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, the Florida Symphony, Tampa, the Civic Orchestra Chicago, the Toronto Conservatory Orchestra, the Northwestern University Summer Symphony, the Santa Cruz Symphony, California, the Western Australia Symphony Orchestra, Perth, the Aguascaliente Symphony Orchestra, Mexico, and the Osaka Philharmonic Orchestra. |

This interview was recorded in a rehearsal room at Orchestra

Hall in Chicago, on October

16, 2003.

Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNUR a month later. This

transcription was

made and posted on this

website in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.