A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

In the Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (MGG) article on the American Symphony, Ludwig Finscher hails Gloria Coates’s symphonic works as “the spirit of an expressionistic-apocalyptic-mystical world view.” Kyle Gann writes of her chamber music, “The sparer context of these chamber works sounds solidly American…a rustic stolidity, a willingness to walk firmly forward off the beaten paths…an American through and through.”

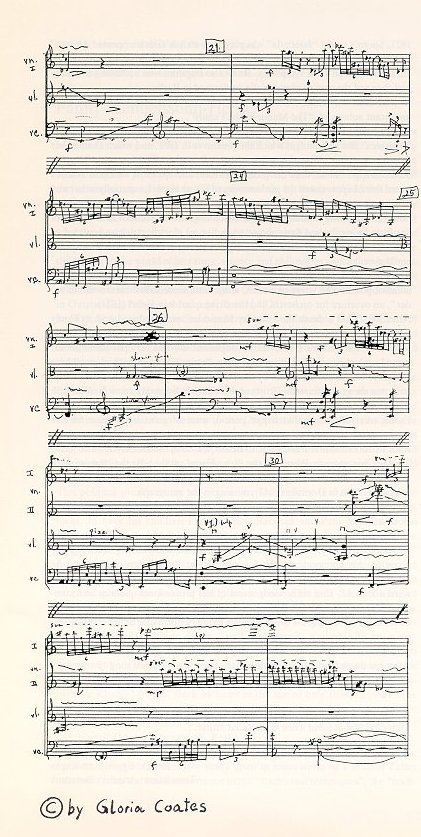

While maintaining a residence in the United States, Gloria Coates has lived in Europe since 1969 where she has promoted American music both in organizing a German-American Music Series (1971–1984), writing musicological articles, and producing broadcasts for the radio stations of Munich, Cologne, and Bremen. From 1975 to 1983 she taught for the University of Wisconsin’s International Programs, initiating the first music programs in London and Munich. She has been invited to lecture on her music with performances in India, Poland, Germany, Ireland, England, and the United States at Harvard, Princeton, Brown, and Boston Universities. Gloria Coates’s breakthrough came with the 1978 première of a work composed in 1973, Music on Open Strings, at the Warsaw Autumn Festival, a work for string orchestra in which the strings retune. It proved to be the most discussed work at the festival and throughout the European press. In 1986 it was a finalist for the KIRA Koussevitzsky International Award as one of the most important works to appear on record that year. Festivals and artists performing her compositions include March Music (Berlin Festival), New Music America (New York), Montepulciano Festival (Italy), Dresden Festival, Warsaw Autumn, Dartington (England) and the Aspekte Festival Salzburg, with artists such as the Kronos Quartet, the Kreutzer Quartet, and the Crash Ensemble Dublin. Orchestras to have performed her works include the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Polish Chamber Orchestra, Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra, Stuttgart Philharmonic Orchestra, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, St Paul Chamber Orchestra, Munich Chamber Orchestra, Radio Bucharest Orchestra, Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, and the New Century Chamber Orchestra of San Francisco. She has written 16 symphonies and other orchestral pieces, 9 string quartets, chamber music, numerous songs, solo pieces, electronic music, and music for the theatre.

|

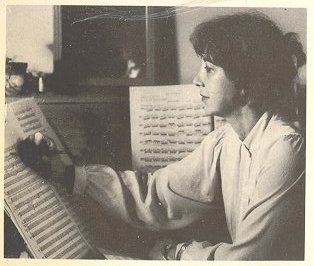

Born in, Wisconsin, Gloria Coates began

composing and experimenting with overtones and clusters at the age of

nine. Her musical intuition has led her to ever widening visions and

experiences. She considers both Alexander Tcherepnin, who encouraged

her composing since she was 16, and Otto Luening, to have been her

“gurus.” Her studies took her from Chicago and Louisiana (with a

Masters Degree in Composition), to New York’s Cooper Union Art School,

and Columbia University for postgraduate studies in music composition.

Born in, Wisconsin, Gloria Coates began

composing and experimenting with overtones and clusters at the age of

nine. Her musical intuition has led her to ever widening visions and

experiences. She considers both Alexander Tcherepnin, who encouraged

her composing since she was 16, and Otto Luening, to have been her

“gurus.” Her studies took her from Chicago and Louisiana (with a

Masters Degree in Composition), to New York’s Cooper Union Art School,

and Columbia University for postgraduate studies in music composition.  BD

BD BD

BD GC

GC