A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: Is it ever good

enough?

BD: Is it ever good

enough? RC:

Absolutely. It’s a lot of different

acts, a lot of little stories which are two or three

minutes by a certain composer. If you sing some song by

Schumann, by Fauré, by Debussy, you jump to a genre which is

light and funny or heavy or dramatic

or sad. So it’s a kind of like being a clown in the circus.

When they laugh, they jump and they do

everything they are to do. We are a little bit like this in

recitals. We have to jump from two minutes of a sad

story, and then the next one is going to be a light one, a funny

one. The Fauré one is going to be French, and then we do

one in

German or Spanish and even English. So it is a kind of a

gymnastic, which is fun to do. I might say it is

a challenge, a fantastic challenge. But still, you are alone in a

certain way, with the music and the

accompanist, but really alone to create a little story, one after

another. If you sing Tosca, for instance, you are

Tosca all the way through, changing according to what’s

happening, but it is still this woman. In recital, it

is completely different. But for me, a recital which is

well performed, well done, is much more interesting than the

opera! For me it was a

fascinating world of imagination or creation. You are really

alone with the pianist and the music. On the stage in an opera,

you have a colleague, orchestra, costume, a wig, make up and so

on. You don’t show your real self. In

a recital, you have to be more open, more exposed.

RC:

Absolutely. It’s a lot of different

acts, a lot of little stories which are two or three

minutes by a certain composer. If you sing some song by

Schumann, by Fauré, by Debussy, you jump to a genre which is

light and funny or heavy or dramatic

or sad. So it’s a kind of like being a clown in the circus.

When they laugh, they jump and they do

everything they are to do. We are a little bit like this in

recitals. We have to jump from two minutes of a sad

story, and then the next one is going to be a light one, a funny

one. The Fauré one is going to be French, and then we do

one in

German or Spanish and even English. So it is a kind of a

gymnastic, which is fun to do. I might say it is

a challenge, a fantastic challenge. But still, you are alone in a

certain way, with the music and the

accompanist, but really alone to create a little story, one after

another. If you sing Tosca, for instance, you are

Tosca all the way through, changing according to what’s

happening, but it is still this woman. In recital, it

is completely different. But for me, a recital which is

well performed, well done, is much more interesting than the

opera! For me it was a

fascinating world of imagination or creation. You are really

alone with the pianist and the music. On the stage in an opera,

you have a colleague, orchestra, costume, a wig, make up and so

on. You don’t show your real self. In

a recital, you have to be more open, more exposed. BD: Did you change

your technique at all for a small

house or a big house?

BD: Did you change

your technique at all for a small

house or a big house? BD: What’s the purpose of music?

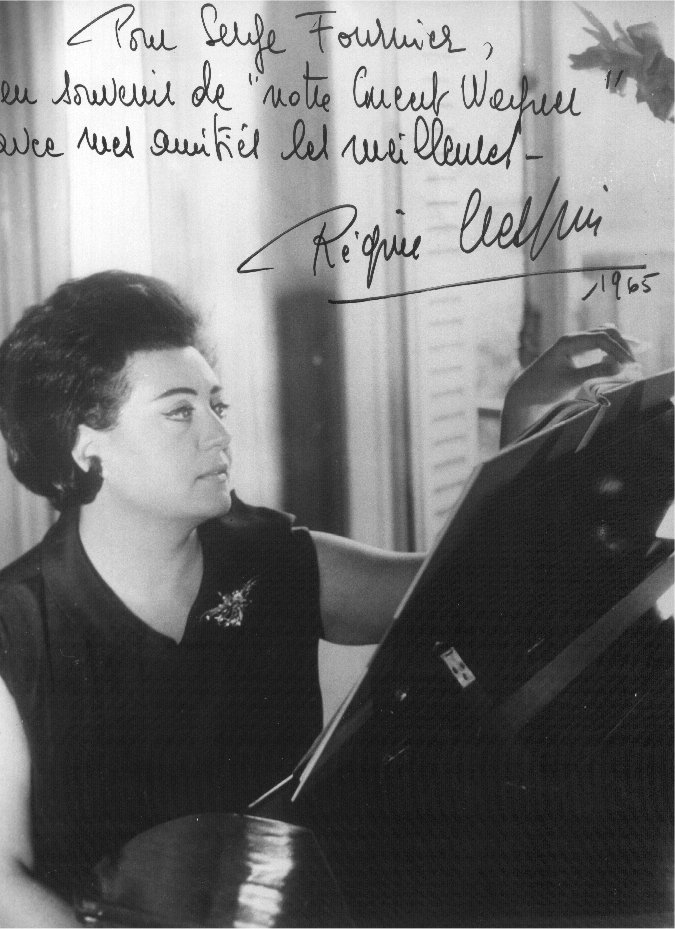

BD: What’s the purpose of music?Regine Crespin, French Opera Diva Dies at 80 by Tom Huizenga July 6, 2007 - Regine Crespin, one of France's greatest opera singers died Wednesday in Paris. She was 80 years old. Crespin was born in Marseilles and came to singing late, at age 16, a result of not passing the entrance exams for college. She made her opera debut in 1948 in Reims in the role of Charlotte in Massenet's Werther, and began to make a name for herself singing in other regional opera houses in France. Crespin's breakthrough came in Bayreuth, the German town which hosts the annual Wagner festival in the opera house built by the composer. When she sang for Wagner's grandson Wieland, who ran the festival, she had to perform Wagner's music in French as she had not learned the original German. She was hired, quickly got a German vocal coach, and made her Bayreuth debut in 1958 in the pivotal role of Kundry in Wagner's Parsifal. As her international career expanded Crespin began to make records. Critic John Steane has written eloquently about Crespin, calling her "one of the great singers on record." But, he points out, not everyone will be immediately drawn to her voice. "Her singing is an acquired taste that becomes addictive," he writes. "The voice itself (strong as it is, and beautiful at a pianissimo) is unlikely to register as particularly rich or pure or even as original." Among the records regarded as her best is the 1963 recording of the song cycle Les Nuits D'ete by Hector Berlioz. Steane focuses on the song "L'Absence," particularly the opening word "Reviens." Steane appreciates the care Crespin takes with that single repeated word, like a call out to a lover. "We feel the voice going out into the distance," he writes. "The first 'reviens' is shaded down to make the echo; the last syllable grows as a call sent out into a valley." Crespin had many triumphs in her career, including singing the role of the Marschallin in Richard Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier both on record—with conductor George Solti—and on stage. She also won rave reviews for her collaborations with soprano Birgit Nilsson, especially her portrayal of Sieglinde to Nilsson's Brunhilde in Wagner's Die Walküre at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. In her later years Crespin was an effective voice teacher, giving master classes at Mannes College of Music, in New York. |

This interview was recorded at the Opera House in Chicago on

March 29,

1996.

Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNIB two days later, and again in 1997. A portion

was also included in the group of Jubilarians

posted on the website of Lyric Opera

of Chicago to celebrate their 50th Anniversary. This

transcription was

made and posted on this

website in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.