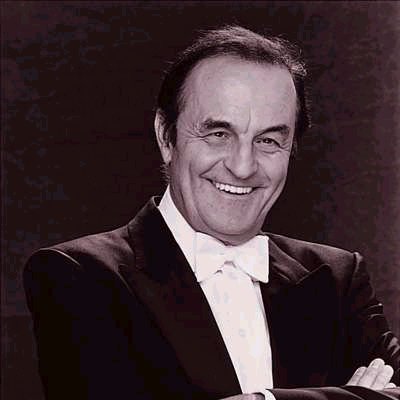

Conductor CHARLES DUTOIT

In Conversation with BRUCE DUFFIE

Conductor CHARLES DUTOIT

In Conversation with BRUCE DUFFIE

With a long and distinguished career already, the biography of conductor Charles Dutoit is filled with impressive details. In order not to omit anything of special significance, the following few paragraphs have been provided by his record company...

Throughout a career that has energetically spanned the globe and mined the riches of orchestral repertoire, Charles Dutoit has exhibited a passion for excellence and insatiable discovery. Renowned for polished and idiomatic interpretations of an eclectic array of musical styles, he regularly collaborates with the world's pre-eminent orchestras and soloists.Since his debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1980, Charles Dutoit has been invited each season to conduct all the major orchestras of the United States, including those of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, Pittsburgh and Cleveland. He has also performed regularly with all the great orchestras of Europe, including the Berlin Philharmonic and Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra as well as with all the London orchestras, the Israel Philharmonic and all the major orchestras of Japan, South America and Australia.

Charles Dutoit has also recorded extensively for Decca, Deutsche Grammophon, EMI, Philips, CBS, Erato and other labels with American, European and Japanese orchestras. His more than 170 recordings, half of them with the Montreal Symphony, have garnered more than 40 awards and distinctions around the world. For 25 years (1977 to 2002), Charles Dutoit was Artistic Director of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, a dynamic musical partnership recognized the world over.

Since 1990, he has been Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra's summer festival at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center in upstate New York. Between 1990 and 1999, he also directed the orchestra's summer series at the Mann Music Center in Philadelphia, and led them in a series of distinctive recordings. From 1991 to 2001, Charles Dutoit was Music Director of the Orchestre National de France with whom he made a number of critically lauded recordings and toured extensively on the five continents. In 1996, he was appointed Principal Conductor and in 1998, Music Director of the NHK Symphony Orchestra (Tokyo) with whom he has toured Europe 3 times, the United States, China and Southeast Asia.

When still in his early 20’s, Charles Dutoit was invited by Von Karajan to lead the Vienna State Opera. He has since conducted regularly at Covent Garden, the Metropolitan Opera and the Deutsche Oper in Berlin. He also led a highly acclaimed new stage production of Berlioz's masterpiece Les Troyens at the Los Angeles Music Center Opera. In 2003, he started to conduct a cycle of Wagner’s operas, The Flying Dutchman and the complete Ring Cycle at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires.

Charles Dutoit has always been interested in working closely with student orchestras and his frequent collaborations include the Orchestra of the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, the Julliard Orchestra in New York, the Civic Orchestra in Chicago and the UBS Verbier Festival Orchestra in Switzerland. He was Artistic Director of the Sapporo Pacific Music Festival for three seasons and is presently Music Director of the Miyazaki International Music festival in Japan and Music Director of the Canton international Summer Music Academy (CISMA) in Guangzhou (Canton), China. He has made ten documentary films for NHK Television in Japan for a series entitled Cities of Music featuring ten musical capitals of the world.

In 1988, Charles Dutoit was invested as Officier, and in 1996 as Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the government of France. In 1991, he was made Honorary Citizen of the City of Philadelphia. In 1995, the government of Québec named him Grand Officier de l'Ordre national du Québec. He is the recipient of two awards by the Canadian Conference of the Arts, both in recognition of his distinguished service and exceptional contributions to music in Canada. In 1998, Charles Dutoit was invested as Honorary Officer of the Order of Canada, the country’s highest award of merit whose honorary recipients include John Kenneth Galbraith, James Hillier, Nelson Mandela, The Queen Mother, Vaclav Havel and Boutros Boutros-Ghali.

Charles Dutoit was born in Lausanne, Switzerland and his extensive musical training included violin, viola, piano, percussion, history of music and composition at the Conservatoires and Music Academies of Geneva, Siena, Venice and Boston. A globetrotter motivated by his passion for history and archaeology, political science, art and architecture, Charles Dutoit has traveled and visited so far 172 countries. He maintains residences in Switzerland, Paris, Montreal, Buenos Aires and Tokyo.

In March of 1986, the Montreal Symphony hit the road again, and

Chicago was the final stop of their tour. On that busy day, I had

the pleasure of sharing a half hour with the Music Director at his hotel,

and here is what transpired . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: As a conductor, what do you expect from an audience that comes to one of your concerts?

Charles Dutoit: I expect them to listen carefully and to make as little noise as possible. Unfortunately, this is not possible in Canada because we have these hard winters and people are coughing all the time. In the heart of the winter that is very difficult, but I expect them to enjoy the program that we're giving them, especially trying to interest them in different fields and certain modern music as well.

BD: Then how do you balance programs with old works, new works, standard works, contemporary works, etc.?

CD: As Music Director in a city, you're responsible for educating the public. "Educating" is a big word, but you need to at least inform the people what's going on around them. So I try, of course. In this part of the world, we have some problems with the box office, so we have to be careful to have programs that are well-balanced so people will just come to the concerts. But I think it's essential that they're informed about what is going on. We just played a new concerto which was commissioned by Isaac Stern. We gave the North American premiere a month ago in Montreal, and repeated it three days ago in Boston and last night in Carnegie Hall. I found it interesting that the New York performance was sold out. Of course we also played some Tchaikovsky to balance the programs.

BD: Do you ever feel that you're force-feeding the public the new works?

CD: When we have to sell a hall with 3000 seats for two or three nights, you can't expect everybody to be interested in modern music. Everybody has a different imagination why they go to a concert. But still, if we don't do anything that will do it. That's my philosophy.

BD: Do you feel that concerts should be art, or should the by entertainment?

CD: It's a combination of both. For many people who go to a concert after a big day of work, hearing the music they know makes them love it. That's normal. On the other hand, we have the responsibility to cover the modern composers, to inform the public of new things, and if just ten people leave saying that they learned something, then, I think, it's a plus.

BD: Are there some modern works that really should take their place along with the Beethoven Symphonies and Mozart Concertos?

CD: Oh yes, sure. First of all, it depends on what you call "modern." I try to bring all sorts of new names who sound more modern, but I don't believe in "modern music concerts." I don't think it's healthy to build a program only around modern music and give these concerts for specialized crowds, for those who would just come because they are interested in modern music. I think you miss your goal in doing things like that. Those works should be put together with other pieces so the public could be informed and perhaps interested. This is they way the relation should be.

BD: Is it the same with romantic composers? Should there not be all-Beethoven concerts, or all-Brahms or all-Mozart?

CD: It depends on what you want to do. It's very possible to have an only Brahms or Beethoven concert. You have those every year, but you cannot have a series. If you have all Beethoven in the series, people ask, "What are you gonna do next?" You have got to save that for a few years. After all, this is the best music, you know.

* * * * *

BD: Do you conduct differently in concert and in the recording studio?

CD:

Not really, no. Our recordings are really live performances except

they don't take place in our hall. In Montreal, we record in a church

outside of the city, so it's a different acoustical environment.

But we have so little time that usually we can only do two takes and a

few corrections here and there. The only concern when I hear the

first take is to revise balance of the orchestra when I see things don't

sound the way they should. We work for a company that prefers to

have us balance the orchestra for them. Other companies don't care.

They put up a forest of microphones and have sixteen tracks, and then they

manipulate the sound the way they like in the studio and remix completely

the orchestra. We prefer to have a natural sound. Therefore,

I have to adjust these problems immediately.

CD:

Not really, no. Our recordings are really live performances except

they don't take place in our hall. In Montreal, we record in a church

outside of the city, so it's a different acoustical environment.

But we have so little time that usually we can only do two takes and a

few corrections here and there. The only concern when I hear the

first take is to revise balance of the orchestra when I see things don't

sound the way they should. We work for a company that prefers to

have us balance the orchestra for them. Other companies don't care.

They put up a forest of microphones and have sixteen tracks, and then they

manipulate the sound the way they like in the studio and remix completely

the orchestra. We prefer to have a natural sound. Therefore,

I have to adjust these problems immediately.

BD: Do those other companies, which use the sixteen tracks, take the control of the orchestra out of your hands?

CD: Mostly, yes. I would not like to do that. I have done several recordings on sixteen tracks and I don't think it's successful at all. If you don't do it the way they want, they just push a button and all of a sudden you have things getting in or getting out, and what emerges is artificial. I have no real control of the final result, and I don't think it's good at all.

BD: Are those kinds of recordings frauds?

CD: Well, yes and no. It is in a way, but it's the final result which counts. If you're satisfied with the final result, why not? For instance, jazz music is recorded that way, but they have specific effects and things like that which they put in one channel. Personally, I think that an orchestra has a certain sound which you can preserve, and the recording company should try to record the sound of that orchestra. They should be more careful in finding the right environment to record the orchestra instead of doing it later by themselves. In Montreal, we're lucky to record in that church, but the orchestra sounds beautiful there. London Records have lots of technique, and they record that sound there in the most musical way. There is no manipulation. If you hear something too loud in one of our recordings, it's not the engineers' fault, it's our fault.

BD: Blame the conductor rather than the producer.

CD: Yes, that's right.

BD: Do you then try to get that same sound you hear in Montreal when you tour to Carnegie Hall or Orchestra Hall or other places?

CD: Well, we usually go home very frustrated because we find all these beautiful halls in the states and we don't have that in Montreal. Mind you, our hall is not bad except that it is not a concert hall but rather it's a so-called multi-purpose hall. It's a little too bright and clear, and lacks warmth. The other day we played in Boston and last night in Carnegie Hall, and those halls make our lives so easy. The musicians can relax and really play. They don't have to rape their instruments to get more sound out of them. It's really beautiful how civilized the sound can be in a hall that responds so well. When we record in our church, we have the same problem. There's a low brilliancy like I'm talking about.

BD: Do you bring your own dampers or cloth drapes or acoustical baffles to try to help the sound in the recordings?

CD: No. In the recording studio there is nothing except a curtain somewhere because there's a little too much reverberance when we have a small group. It depends upon how large the orchestra will become, but it's really nothing. We just concentrate on the reverberance. The quality of the sound is basically there. We don't have that quality in Montreal. Orchestra Hall, here in Chicago, is beautiful and the concerts are brighter than in Carnegie Hall or in Boston. It's a wonderful hall here.

BD: You have conducted the Chicago Symphony...

CD: ...but never in this hall, only at Ravinia. I did bring my orchestra here several years ago. [Note: In the years since this interview, Dutoit has conducted the Chicago Symphony in Orchestra Hall on several occasions.]

BD: Do you try to get the same sound from your orchestra as you get from the Chicago Symphony?

CD:

No, no, because we have a different sound altogether. They have certain

characteristics of sound. It's a ritual that the Chicago Symphony

sounds a little like the hall, or vice versa. The hall sounds a little

like the Chicago Symphony. There's an osmosis between the hall and

the orchestra, like there is in Boston or Vienna. I think it's true

when an orchestra plays all the time in the same environment, they have

the sound in their ear and in their mind. Even when they are traveling,

they try to recreate the sound they are used to. It takes a little

adjustment. This is also true in our case, except that I basically

think the Montreal Symphony produces less sound altogether than the Chicago

Symphony. I'm not trying to have a powerful sound. Powerful,

yes, but it's not as powerful as Chicago. The Chicago Symphony has

an enormous sound.

CD:

No, no, because we have a different sound altogether. They have certain

characteristics of sound. It's a ritual that the Chicago Symphony

sounds a little like the hall, or vice versa. The hall sounds a little

like the Chicago Symphony. There's an osmosis between the hall and

the orchestra, like there is in Boston or Vienna. I think it's true

when an orchestra plays all the time in the same environment, they have

the sound in their ear and in their mind. Even when they are traveling,

they try to recreate the sound they are used to. It takes a little

adjustment. This is also true in our case, except that I basically

think the Montreal Symphony produces less sound altogether than the Chicago

Symphony. I'm not trying to have a powerful sound. Powerful,

yes, but it's not as powerful as Chicago. The Chicago Symphony has

an enormous sound.

BD: Do you adjust the specific sound you want to the repertoire you're playing?

CD: Yes, you have to. Absolutely. But this, of course, is style again. We always talk about the sound of an orchestra and I think that it's not correct. We should talk about the sound of the music we play. We agree that playing in a certain environment, you develop a certain sound of your hall and it is also the sound of your conductor. Every conductor has a certain insight of a certain sound which he tries to get, especially when he works often with the same orchestra. Little by little, this sound becomes more obvious, but basically we all do try to find the sound of the music we play. This seems to be obvious, but it's not always the case that so-and-so plays a certain sound for Schumann and another sound for Brahms. I picked those two composers because I think they are very close.

BD: Moreso than Schumann and Debussy.

CD: Yes. Schumann and Debussy are two different cuisines, but within the same cuisine, you have different sorts of sounds. Schumann's has more fervor and Brahms is more full. Whenever I conduct a Schumann symphony, I always try to have a different atmosphere and a different sound than I would in a Brahms symphony. Schumann has more fervor, more tension than Brahms, who is more relaxed.

BD: Does the sound you're able to produce, or the sound you are trying to get, have an impact on your choice of repertoire?

CD: No, I think it's eventual. When we started to make recordings with the orchestra, we had to find a strategy because there are so many recordings on the market today and I had personally done quite a few. But in order to make this operation successful in Montreal. we had to find something which was going to be successful. When you start a new thing, it's better to hit the front page than to stay between all the time. Montreal has a certain French flavor, they use the French language, I was born in Lausanne, and my mentor was Ernest Ansermet, who had been closely associated with the Suisse Romande Orchestra from the beginning of this century and was an exclusive London artist for thirty five years. When he died, there was a big gap in the catalogue, so we tried to find a way to fill that gap while creating a general sort of thing.

BD: Do you still feel you are trying to fill his shoes?

CD: Perhaps. We started to record Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé and once that was decided, I prepared the orchestra to play that piece. It had to be successful. It was very successful, and we eventually recorded all the works by Ravel. Obviously, I prepared the orchestra for a success in that repertoire. Now we have changed a little, but I still think, from that experience, the orchestra has a certain clarity of sound, a definition, and strong feelings for differentiations, and a subtle use of colors, maybe more than other orchestras. It's a very well-balanced orchestra in that sense. I'm not talking about balancing the sound, such as the need for less brass or less percussion. It's not as simple as that. The balance of an orchestra is very subtle. If you have a chord with two horns and two clarinets and two bassoons, and one of those instruments plays their note too softly, then the whole chord doesn't sound correctly. As you know, each note develops an enormous amount of harmony and in order to achieve that bunch of harmonies that we need to produce a color, we have to be very careful in having the most impeccable balance within these chords. The intonation must be extremely good, so all these harmonies develop that flavor together instead of conflicting each other. That is what creates that kind of sound. These are technical things, but there are hundreds of things like that which are so important in our profession.

BD: As the conductor, are you expected to know all of the subtleties of every instrument all the way down the line?

CD:

Yes, absolutely. I have to. I think a conductor is also a trainer.

An orchestra is an instrument and you need somebody to play this instrument.

When you get a hundred musicians, you can say, "How wonderful, they play

by themselves." It is true, and they will develop a common way of

playing, but if you do not work with an orchestra, it cannot go up.

It's like a great virtuoso who doesn't practice any more. You have

to clean the orchestra constantly to keep things going and improving.

CD:

Yes, absolutely. I have to. I think a conductor is also a trainer.

An orchestra is an instrument and you need somebody to play this instrument.

When you get a hundred musicians, you can say, "How wonderful, they play

by themselves." It is true, and they will develop a common way of

playing, but if you do not work with an orchestra, it cannot go up.

It's like a great virtuoso who doesn't practice any more. You have

to clean the orchestra constantly to keep things going and improving.

BD: Is conducting something that can be taught in a conservatory, or must you learn by doing it?

CD: I think it's a matter of inclination first of all. It also depends on how much you know about the job. It takes years and years and years to know that conducting is not waving in front of an orchestra and animating until something works. If you're a guest conductor and you enjoy that, you go and face a wonderful orchestra and try to have as much pleasure as possible and make a good concert. But if you are the Music Director, you're responsible for an orchestra. Especially if you have young people, you have to educate these people. They have to fit in one school. One has to find a common way to play a certain score or a certain style, and this is up to the conductor because everybody has a different opinion about these things, or a different approach, or different reasons to think it should be that way or another way. The conductor actually develops a kind of habit to go straight to the point as efficiently as possible and as quickly as possible.

BD: Are there some orchestras where it is more of a collaborative effort rather than a dictatorial position?

CD: The great orchestras of the world have their own personality and you work with them to make the best music possible in the moment, on the spot. I think the dictatorship is really over. It doesn't exist any more.

BD: Are there some pieces which are rarely played that you feel should be put back into the repertoire?

CD: Oh yes, there are many. There are so many. The problem is it's very difficult to play everything because the repertoire is huge. In the past couple of years in Montreal, we've done so many different things that today, when we play a simple early Beethoven symphony once in awhile, it seems like it's a new piece, which is refreshing. And there are many modern pieces which should be played. We cannot just repeat everything, but it depends if you have time to bring things back. We have just so many weeks with so many concerts, so unless you decide that you will play one particular symphony every four years just to see what the conductor will do with it, a lot of music is neglected. Take Haydn, for instance. He has given us so many symphonies that are the most beautiful pieces ever written. I don't know any orchestra that has played all of them. And there are so many things in the modern repertoire which are totally neglected after having been performed once. The Tourangalîla-Symphonie by Messiaen is a big work that is played too rarely. It's a wonderful piece, but it's long. I could tell you of a hundred others like that.

BD: Is it the responsibility of the Music Director or the orchestra management to commission new works?

CD: I think it's a collaboration, but basically the Music Director is in charge of those projects, and then the management must find a way to finalize them.

* * * * *

BD: Have you done some operas?

CD:

I'm not an opera conductor at all. I do it as a hobby. I like it,

I love it, but I started in the orchestra myself being a violinist and

a viola player, and I work as a symphony conductor more than as an opera

conductor. I have not done many operas, but I've tried to do something

new each year. If it's not in the opera house, then it's a recording.

I have to learn all these things. I will never be somebody who will

work at the Met or Covent Garden or La Scala and conduct fifteen operas

in a season because it's not my profession. But I love to do opera,

and have done most of the Puccini operas. I have done a lot of operas

in concert including Pelléas et Mélisande, as well

as big acts of Wagner. I've done Tales of Hoffmann and Faust,

and I would love to do the Mozart operas. I was very scared to do

these because I think they are among the highest achievements of our civilization

and somehow I never felt I could do them justice. I have to live

a little more. I've done so much Mozart that I think I really should

turn the page.

CD:

I'm not an opera conductor at all. I do it as a hobby. I like it,

I love it, but I started in the orchestra myself being a violinist and

a viola player, and I work as a symphony conductor more than as an opera

conductor. I have not done many operas, but I've tried to do something

new each year. If it's not in the opera house, then it's a recording.

I have to learn all these things. I will never be somebody who will

work at the Met or Covent Garden or La Scala and conduct fifteen operas

in a season because it's not my profession. But I love to do opera,

and have done most of the Puccini operas. I have done a lot of operas

in concert including Pelléas et Mélisande, as well

as big acts of Wagner. I've done Tales of Hoffmann and Faust,

and I would love to do the Mozart operas. I was very scared to do

these because I think they are among the highest achievements of our civilization

and somehow I never felt I could do them justice. I have to live

a little more. I've done so much Mozart that I think I really should

turn the page.

BD: Do you have to start understanding the voice before you can do operas?

CD: Of course, yes. But I work a lot with voices through all the concert repertoire. I was actually a Chorus Master myself in Switzerland, and I have done all the oratorio repertoire, and the Beethoven Mass, the Bach Passions, the Brahms Requiem, the Verdi Requiem. So it's not that, but you develop a different approach if you were totally and completely in the opera world. But after all, there is only one way to look at it, and that is to make music, because whatever you do, you make music. And whether you are in the pit or on the concert platform, its the same thing, the same approach. You are bound to have some little problems in your performance which have nothing to do with music, things like synchronizing certain elements on stage. It's a little more impossible sometimes, maybe, but I think it's purely making music or music-making.

BD: There's just the added dimension of the theatrical stage?

CD: I would like to say that I find conducting operas easier, in a way, than conducting a pure symphony. If you do an opera, you know what the music means because it has been composed on a certain drama to illustrate some scene. And when you are conducting a dramatic opera, you are the stage and everybody needs support. And they're supporting you as well. Now, when you do a symphony, it demands much more from your imagination because it's more abstract.

BD: Even a programmatic symphony?

CD: Yes, in a way. If you think of a symphony by Liszt, you can follow the program really clearly. But even with the Symphonie Fantastique of Berlioz, there is a program that you think of when you're listening. You know the peaks, you know whatever it is he wants to do, but the music is still pure.

BD: So it's open to more interpretation, then?

CD: Yes, more imagination. You've got to get into it, you know.

BD: How do you feel about making cuts in scores?

CD:

No cuts. Absolutely no cuts. Today we're a little bit crazy

because people are making all these repeats. I don't know whether

this is right or not, but it seems that we are in a period when everybody

should make all the repeats. I think it is a fashion. But cutting

is different. You know, though, some cuts are suggested by the composer.

I suppose some composers were so used to these kinds of problems that they

preferred to make the cuts themselves. In many of his works, Liszt

prepared possibilities to make cuts. Rachmaninoff recorded his Third

Piano Concerto with cuts himself. Maybe people were less fussy

than we are today, but basically I think we should not make cuts.

In the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, there are certain little editings

which I find totally stupid, but they are traditional. Small adjustments,

four bars here, eight bars there, made by Auer at the time of the premiere.

But I encourage young people today to just try to play the original.

It's the same in the Lalo Symphonie Espagnol. It has five

movements, but tradition has it to only play four. Somebody had this

crazy idea idea one day and it was even taught that way at the Conservatory.

Today, I refuse to do that work with a soloist who wants to play only four

movements. I think it's abnormal. It was meant as a piece in

five movements and that's it. I refuse, or I change the program.

CD:

No cuts. Absolutely no cuts. Today we're a little bit crazy

because people are making all these repeats. I don't know whether

this is right or not, but it seems that we are in a period when everybody

should make all the repeats. I think it is a fashion. But cutting

is different. You know, though, some cuts are suggested by the composer.

I suppose some composers were so used to these kinds of problems that they

preferred to make the cuts themselves. In many of his works, Liszt

prepared possibilities to make cuts. Rachmaninoff recorded his Third

Piano Concerto with cuts himself. Maybe people were less fussy

than we are today, but basically I think we should not make cuts.

In the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, there are certain little editings

which I find totally stupid, but they are traditional. Small adjustments,

four bars here, eight bars there, made by Auer at the time of the premiere.

But I encourage young people today to just try to play the original.

It's the same in the Lalo Symphonie Espagnol. It has five

movements, but tradition has it to only play four. Somebody had this

crazy idea idea one day and it was even taught that way at the Conservatory.

Today, I refuse to do that work with a soloist who wants to play only four

movements. I think it's abnormal. It was meant as a piece in

five movements and that's it. I refuse, or I change the program.

BD: What other advice do you have for young performers coming along?

CD: Pianists or violinists are more fortunate than conductors because, if they are gifted, they can call for an audition and be heard by a conductor or a manager. They have the possibility to be heard and eventually get some concerts. For a conductor, it's much more difficult because a conductor without an orchestra is nothing much. What I would like to say is that people seem to be more and more involved in making a career as such. Teaching is also taught, and in a profession like ours, you have to make a career one way or the other. I think our society is a little dangerous at this point because it tends to squeeze the lemon much too early. I see many young people without much knowledge of what the world is all about, with a very limited culture in general, going around the world living the international life from one concert hall to the next. They take on this so-called first class, jet-set life, and once you start, you have no time to really think about what you do, to read and to have this intellectual and cultural equipment which is so essential to develop. Therefore, I find it very sad to see some of these young people once they start their career. They don't have enough inside to develop, to be able to cope with that.

BD: Are they burning themselves out?

CD:

Yes. It's the system that builds them and they're ill advised.

I think they should have people who really care about their prospect of

life a little more. It seems that they are advised by people who

want them to make big careers as soon as possible. I find it very

dangerous, and it's very depressing to see a certain emptiness in their

musical work. I think that is something which should be changed.

They should go back to certain values out of that person's past.

CD:

Yes. It's the system that builds them and they're ill advised.

I think they should have people who really care about their prospect of

life a little more. It seems that they are advised by people who

want them to make big careers as soon as possible. I find it very

dangerous, and it's very depressing to see a certain emptiness in their

musical work. I think that is something which should be changed.

They should go back to certain values out of that person's past.

BD: Is this the fault of the teachers, the managements or the performers themselves?

CD: It's a combination of everything. Certainly not the teacher, though. There are some good teachers and some less good teachers, but today, too much drive is placed on the direction toward a career as such, and not enough bounce. They need to make it and also develop as human beings.

BD: Is this problem peculiar to music, or is it something that is general in the whole world today?

CD: Of course we all know people who specialize, especially in the scientific field. But young people today who have talent go very soon to a music school and make it their general education. They win a competition and make a career and they never try to catch up with that. It's more dangerous in our field, I believe.

BD: Despite that, are you optimistic about the future of music?

CD: Oh yes, absolutely. As performers, we are so

privileged to do what we do. I think it's the most wonderful thing

to be a musician. What would society be without music? It's

unthinkable in the civilized world. When the world wants to stay

civilized and develop and find higher values, music is wonderful.

=== === === === ===

- - - - - - - - - - - -

=== === === === ===

Winner of the ASCAP/Deems Taylor Broadcast Award in 1991, Bruce Duffie spent 25 years with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago. His series of programs featuring music and interviews with composers and performers was a popular favorite, and now continues on WNUR-FM, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio. Many of the interviews have been published in magazines and journals over the years, and some are now being posted on this website.

For more information, including a complete list of his guests and links

to those which have been transcribed and posted, visit Bruce

Duffie's Website. He also responds to E-Mail

messages.

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This interview was held in Chicago on March 26, 1986, and portions were

aired on WNIB several times, and once on WNUR. The material was also

used aboard Northwest Airlines in 1988, and was first posted on this website

in October of 2006.