A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

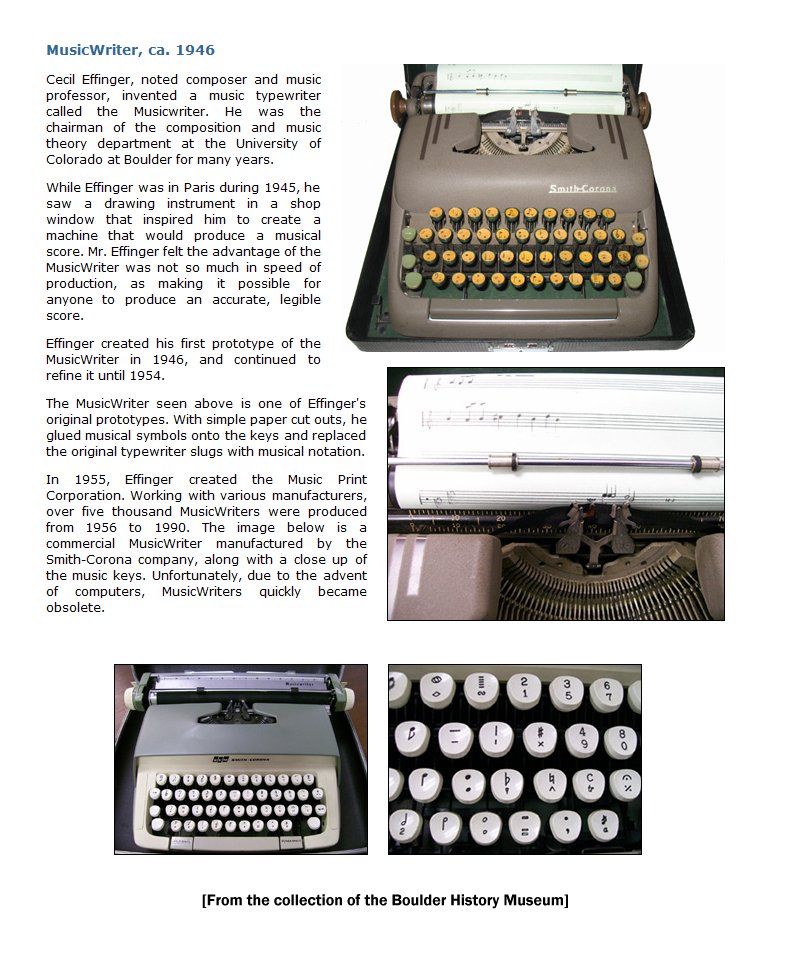

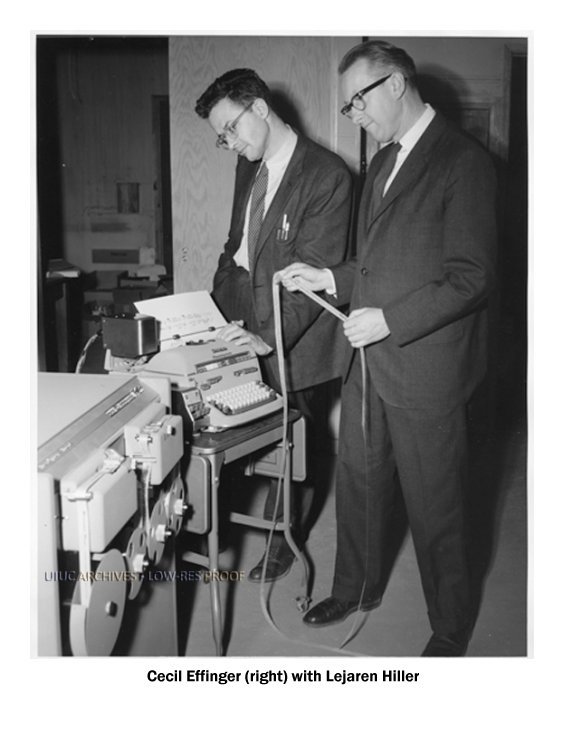

Cecil Effinger (b. 1914, Colorado Springs; d. 1990, Boulder, Colorado) As a young man in Colorado Springs, Cecil Effinger was exposed to such well-known composers as Igor Stravinsky, who came to the small Western town for its natural springs and dry climate. Effinger became an instructor of music at the Colorado College and the first oboist in the Denver Symphony Orchestra in 1935. In 1939, he studied composition with Nadia Boulanger at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau, France. During World War II, he served as director of the 506th Army Band, stationed at Fort Logan in Denver. Shortly thereafter he began teaching at the University of Colorado (CU) in Boulder, where he chaired the Theory and Composition Department for 33 years. He retired from CU in 1981 and served as composer-in-residence from 1981 to 1984. Effinger was a prolific composer. He wrote 31 orchestral works, 7 symphonies, 45 chamber works, 49 choral works, 6 quartets, 3 operas, 3 oratorios, and 3 cantatas. Effinger’s compositions reflect his love for the Western United States, bearing such titles as “The Old Chisholm Trail,” “Variations on a Cowboy Tune,” “Tone Poem on a Square Dance,” and “A Prairie Sunset.” In addition to his contributions to American music, Effinger was also an inventor, producing the musical typewriter in 1954 and the “tempowatch,” to measure tempi, in 1969. |

CE: No. [Both

laugh] It’s the part that I would like to counteract, if

possible, but I’m concerned about the musical appetite in this

country. On the one hand, there are people listening to good

music in droves — more than ever before in history, probably,

due to radio and recordings and so forth. But also, I think

there’s a massive population that is getting a little tired of some of

the less demanding musical utterances. They are more interested

in being

challenged, and therefore are interested in the kind of music we’re

interested in — the so-called, for want of a

better term,

“classical.” I know

some folk tunes that are classical, and I know

some cowboy tunes and some pop tunes that are classics, so it’s a wrong

word, really.

CE: No. [Both

laugh] It’s the part that I would like to counteract, if

possible, but I’m concerned about the musical appetite in this

country. On the one hand, there are people listening to good

music in droves — more than ever before in history, probably,

due to radio and recordings and so forth. But also, I think

there’s a massive population that is getting a little tired of some of

the less demanding musical utterances. They are more interested

in being

challenged, and therefore are interested in the kind of music we’re

interested in — the so-called, for want of a

better term,

“classical.” I know

some folk tunes that are classical, and I know

some cowboy tunes and some pop tunes that are classics, so it’s a wrong

word, really. BD:

You’ve written a great deal of choral and solo vocal music.

Tell me the joys and sorrows of writing for the human

voice.

BD:

You’ve written a great deal of choral and solo vocal music.

Tell me the joys and sorrows of writing for the human

voice.

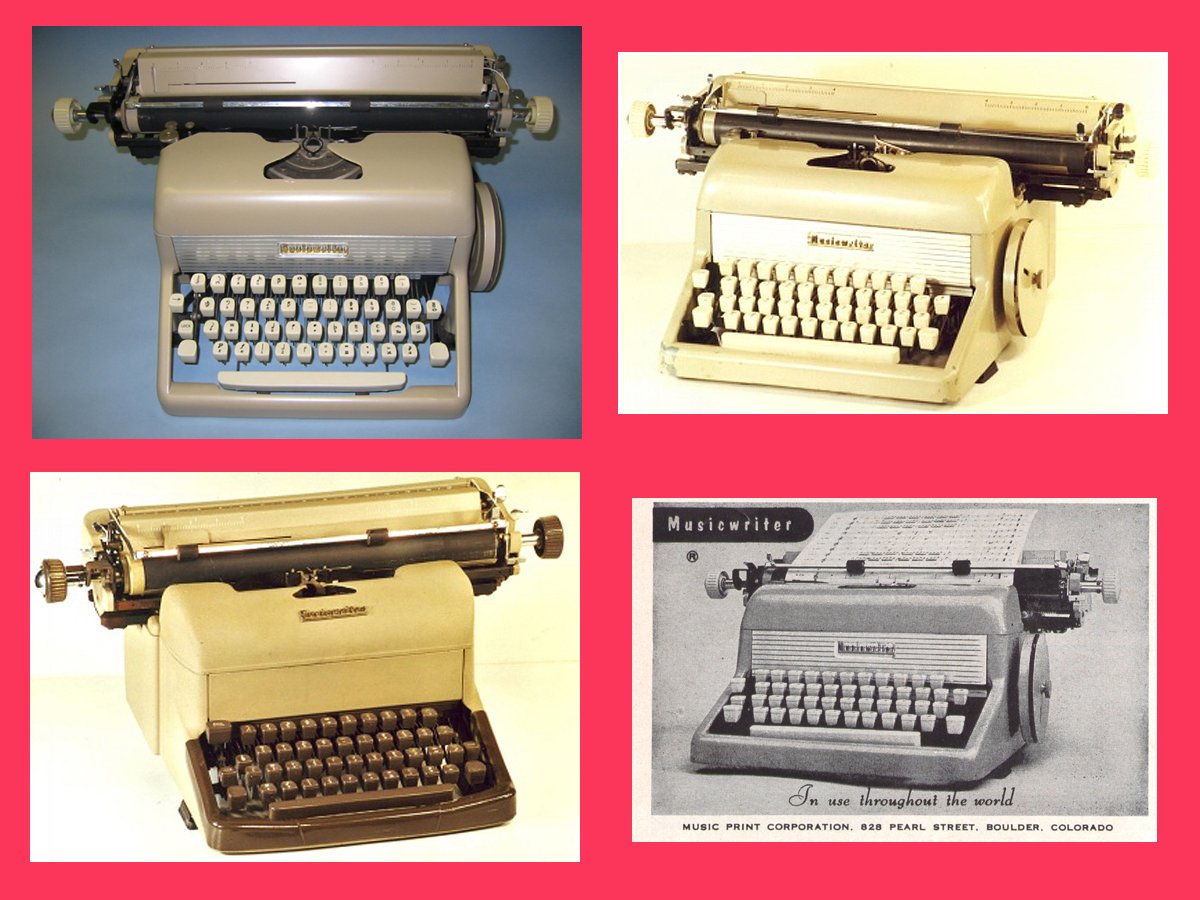

Music: Notes by Typewriter

Time Magazine, Monday, July 11, 1955 After four reels of struggle and starvation, the Young Composer manages to play snatches from his symphony for the Great Conductor, who is entranced. "We will perform it at Edinburgh next month," he promises, and the average moviegoer can go home happily confident that the Young Composer is over the last hurdle on the highroad to success—and perhaps even to Hollywood Bowl. But composers in the audience will have one more worry about the hero: Where will he get the $1,000 or so to pay for having his symphony copied so that it can be played by an orchestra? Cecil Effinger. 40, a music professor at the University of Colorado, whose own compositions, including three symphonies, are well known in the Mountain. States, has been thinking about the $1,000 question since 1945. One day in Paris, he saw an unusual typewriter in a store window, and it got him speculating about a typewriter for music. After investigating and discarding other designs, Effinger came forth last week with a typewriter of 79 characters and a carriage that can be moved freely to produce the most complicated kind of notation. With a little practice, Effinger claims, typists will average about 60 characters a minute (manual copyists average 45). But the advantage, he believes, lies not so much in speed as in an amateur's ability to produce an accurate, legible score suitable for reproduction or for instant use on a music stand. Estimated cost of Effinger's machine: $300. Composer-inventor Effinger expects his biggest market to be the field of education. "Copies are being made in schools every day," he says, "making up examinations, making theses, and so on.'' He warns enthusiastic musical illiterates not to "expect a rush of composers suddenly to sit down behind desks with cigarettes dangling out of their mouths and begin pouring out a ream of symphonies on these machines. The Music Writer will simply be used instead of a pen when it comes to making finished copies." |

CE:

It’s sharp, too.

CE:

It’s sharp, too. CE: Oh,

yes! Oh, yes. I have a wonderful story... There’s all

this talk about computers right

now. I heard this story just this week about an electronics

convention, where there were computers and more computers and robots

and all of this stuff at this trade

show. A manufacturer took a booth, and his sign said, “The

world’s most powerful word processor.” He had

half a million pencils in his display! [Both laugh

heartily] Nothing more powerful than the pencil and the

eraser! Oh of course, you don’t sit at the typewriter; the

typewriter does final copy.

CE: Oh,

yes! Oh, yes. I have a wonderful story... There’s all

this talk about computers right

now. I heard this story just this week about an electronics

convention, where there were computers and more computers and robots

and all of this stuff at this trade

show. A manufacturer took a booth, and his sign said, “The

world’s most powerful word processor.” He had

half a million pencils in his display! [Both laugh

heartily] Nothing more powerful than the pencil and the

eraser! Oh of course, you don’t sit at the typewriter; the

typewriter does final copy.

This

interview was held in Chicago on April 4, 1988. Portions were

used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1989, 1994, and 1999. The

transcription was made in 2010, and posted on this

website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.