Karlheinz Essl

interviewed by

Bruce Duffie

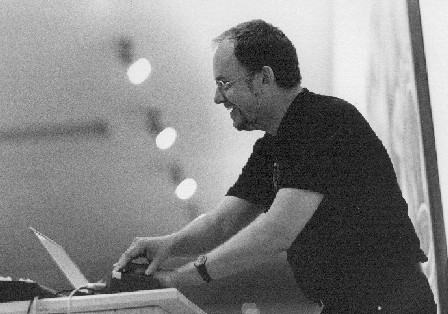

What you are about to read is an interview with composer Karlheinz Essl, which took place in Chicago in March of 1997. Portions of this conversation - along with musical examples - were broadcast in August, 2000, as part of my ongoing series devoted to living composers.

At the end of 2005, the composer himself made this transcription of our chat. He slightly edited what was said and I have made my usual modifications which do not alter the thoughts and ideas, but make them more readable in this visual format. When communicating with Essl, he made it clear to me that these comments do not represent his current feelings, but were how he responded to my questions at the time of our meeting. However, like any creative mind, this process will continue to grow and expand, and any reactions will, of necessity, represent a snapshot of that isolated moment.

Just as an earlier composition will always be of interest, this interview will contribute toward our understanding of the inner workings of the ongoing progress, and should be regarded only as such. For his current thoughts and feelings, visit his website which is updated as he sees fit.

Here, then, is what was said on that visit to the Windy City about a

decade ago . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You started out to be a chemical engineer, then you turned to music. Why did you get out of chemistry?

Karlheinz Essl: Music has a lot to do with chemistry. During my studies of chemistry I was already very active in music, but when I started, it became clear to me that I didn't want to go into business afterwards. So I began studying musicology. At the same time I passed my entrance examination at the University of Music in Vienna and I became a student of Friedrich Cerha.

BD: He is best known for completing Lulu, but he is also a composer in his own right.

KHE: Cerha is a fantastic composer, but he is most widely known for his work on of Lulu.

BD: Music often has to do with mathematics, but you say that it has something to do with chemistry. Is that widely known or just something you discovered?

KHE: Well, it's a nice metaphor. Music exists as little atoms and molecules which are combined with each other, forming new complexes, new entities. In this respect there are some relationships between the concepts of chemistry (or science) and of music - as I see it. This is not the traditional concept of music. It's more like viewing music as sound happening in space. The organization of sound has sometimes to do with the way protons and neutrons are forming new elements by confronting each other.

BD: Are they forming the new elements in the air, or in your brain?

KHE: Of course sound happens in the air - this is its medium. But it becomes music only by listening to it, and listening is a not passive way of deciphering a given code. It is a creative act of perception. In fact, by listening we compose the music in our brain and our heart. As a composer, I do not merely supply a certain code which has to be deciphered by the audience, but rather I open structure which can create different musics in the ear, the brain or the heart of the listener.

BD: Do you expect the listener to put something into your music before it really becomes something?

KHE: I don't expect people to have a certain knowledge or training. The only thing that I hope for is that my audience has an open heart and lets things happen.

BD: Are you aware that it will impact differently on each different listener?

KHE: It is a medium of communication and gives us some knowledge about ourselves. Music, which is so much related to time, is a very nice metaphor of our living and of the struggles in our life that we have. It also has a strong metaphysical component, but sort of abstract. The real life is happening on earth, but music is takes place in the space, outward of our existence.

BD: Does it surprise you what kind of reaction it generates in various audience members?

KHE: Perception is always different, but often the reactions are very emotional with my music. The best basis is if people don't know too much about my technical involvement, or how I manage to come to this music. When they listen to it, however, they normally witness that they have been emotionally touched.

BD: The music is the music and not the process to get to the music?

KHE: Well, what's the music? Amusing... Amusing music... This is Gertrude Stein, isn't it? What is music? It's something fluid, something that is given, but also something that has to be fulfilled by the listeners.

BD: You are giving them something that is almost ready?

KHE: It is ready, but it gets its fulfillment only by the act of listening. It's like a cheque. If I give you a cheque, it is already worth the money, put you have to go to the bank and give it to the cashier in order to be able to spend it and use the money.

* * * * *

BD: Is the music that you write for everyone?

KHE: Principally yes, but it is not elitist. As I said before, the only thing I demand is an open heart and open ears. When I compose music, I don't have a certain audience in mind. I just want to let a vision become true, and I work very hard to achieve it. I think that's a process that never gets entirely to the goal. It's always approaching towards an idea. So, in speaking for myself and my colleagues, we have to compose all our life in order to come closer and closer to that goal. It's always a little step further.

BD: And whenever you made this little step you find there is another little step ahead?

KHE: Of course. And every step I take also shifts my horizon. I will see a little more. Sometimes I'm also able to make a little jump and then I see 10 centimeters further which also gives me more ideas. This has something to do with the tragedy of life. As human beings, at least in our culture, we are forced constantly to continue walking, gaining wisdom and development. That's the way we live, but I can imagine that's not the only way of living. There could be other possibilities of more contemplative ways of living, like in former ages. Sometimes I ask myself, "How did people live in the Stone Age?"

BD: And we had to go through it in order to get here. Do you think we will survive on this earth long enough to where this age we're living in now would be considered a Stone Age?

KHE: I am afraid not. I am very skeptical about it. I hope my children will survive, but I have no longer-range perspective.

BD: Well, with whatever time we have left, are you optimistic about the future of music on Earth?

KHE: I have no concerns about the future of music, because music will go on forever. But I am very concerned about the future of our living on Earth. There are a lot threatening facts. In the arts, we are sometimes very much outside those things, so we reflect them of course. Sometimes an artist has the gift of prophecy to see things in advance, to express it and to find a symbolic representation of these things that could warn us.

BD: Does all of this manifest itself in your music, or is it something that you keep separate from your music?

KHE: I think it should manifest itself, but normally I don't speak about these things.

BD: Why not?

KHE: I hold with what Wittgenstein said, "What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence." That's also the reason why I make music. There are things which you cannot express in words. That's the justification of making arts and music.

* * * * *

BD: You compose. Do you also teach?

KHE: Yes.

BD: What kind of advice do you have for the next generation of composers?

KHE: I would say, "Be alert and sober, have an open mind, challenge your mind, step across borders, and don't trust yourself too much."

BD: Trust others, you mean?

KHE: No. Be always critical, and always strive going beyond the step that you can take. Don't be content with what you already have achieved.

BD: I see. Don't become complaisant. Are you pleased what you see on the paper of your students, the scores that they are coming up with?

KHE: I see a will and a goal and an interest, but of course I also see the problems. Generally, my students are very enthusiastic. Even if they come with some very immature stuff, I know that through the process of work it can become something elaborated and worthwhile.

BD: I assume you get commissions for your works. When you get an offer to write a piece, how do you decide "yes, I will work on it" or "no, I will turn it aside?"

KHE:

It depends mostly on my time.

KHE:

It depends mostly on my time.

BD: You don't have all the time in the world that you want???

KHE: No! I have a family with two children, I am teaching, I am organizing concerts...

BD: Well, let me turn the question around. Do you get enough time to compose?

KHE: I have to take it. As a student, when I was finishing my studies, there was a period where I had to compose many pieces for my final examination. In those two years I was composing day and night, but this is not possible anymore. Normally I compose in phases - two or three month where I mostly compose, and afterwards there is a pause where I have to do other things.

BD: Well, when you get to the point where you have some time to compose, are the ideas there, or do you have to struggle to find the ideas?

KHE: The ideas come mostly from the commissions. Recently someone asked me to write a piece for an orchestra known for their fantastic percussion players. So I suggested to compose a piece for orchestra and 3 percussionists which are not sitting on the stage, but are placed within the audience. I am very much interested in the spatial aspect of music. Immediately I got ideas and imaginations for this piece. For me the instruments and their combinations are very important. Sometimes I challenge myself to finding very bizarre combinations. The Australian "Elision Ensemble" recently asked me for a piece. They have a fantastic guitar player who also plays the electric guitar, and I also played this instrument during my teenage years. I am still fascinated by this instrument but I think it is very difficult to use in the context of non-pop music because the instrument is so much related to this. This was a real challenge. So I used an electric guitar (as a plucked instrument), a saxophone (as a blown instrument), percussion (beaten instruments) and a double bass (which is bowed). One instrument of each kind, but all coming from a Pop context, although I wanted to write a piece that has nothing to do with popular music.

BD: So this would have completely displeased the Pop audience?

KHE: I don't know. Maybe they would have liked it. I wanted to maintain this kind of sound quality. With these instruments you can get an enormous spectrum of sounds, and also form expressions that come with certain types of Pop music I was listening to when I was younger. Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, etc.

BD: Well, if you grew up with Jimi Hendrix and The Doors, why did you abandon them and go into concert music?

KHE: There was a time when I was fed up. I was not any more interested in such kind of music. But before this saturation happened, I came across Stockhausen. When I was 15 I found his writings in our public library. At this time I was playing in a band and we were interested in having a synthesizer, but they were so horribly expensive that we ended up watching them in the music store. If we had had $100,000 we would have bought one. Then I stumbled upon Stockhausen's texts about his engagement in Electronic Music in the 1950s, and I was completely absorbed. Although his articles (in the first two volumes of his "Texte") are very technical, they were, nevertheless, striking. I bought a record of Stockhausen's Kontakte and there were two versions on it - one with electronics, percussion and piano, and the other side only the electronic part. I preferred the pure electronic version by far. I was listening thoroughly to the music and was studying the score, which was huge. So, I became a follower of Stockhausen.

BD: This has nothing to do with the fact that you share his first name?

KHE: That must be pure chance. But my son has the same name as one child of Stockhausen: Simon. I once met Stockhausen and we spent an evening together. It was strange. As a person he is very closed and self-centered.

BD: It sounds like he disappointed you in some of your expectations.

KHE: I had no expectations in this respect because he didn't ever interest me as a person. I was only interested in his music.

BD: Does it bother you if the concert audience is not interested in you, but only in your music?

KHE: No, it does not bother me, but I am always happy if a personal contact happens, if the spark ignites. But that's not the normal thing. However, if it happens, it's something very special, very precious.

* * * * *

BD: Do most of your scores incorporate electronics?

KHE: Not at all. The electronics are only a small segment. I normally do instrumental music in the domain of chamber music and orchestra.

BD: When you are writing a score and you've got it all down and you have gotten to the end and you have put in all the fine touches - how do you know when it is done?

KHE: The end is always clear from the very beginning. The formal plane is the first thing I do. There is no writing, writing, writing and then the end. The beginning and the end are always very clear, and I have to find a way of composing through those starting points.

BD: That is the end of the music. But how do you know when you are finished putting in all of the little marks and making the adjustments?

KHE: Well, there is a certain point where everything is elaborated in a way that you would not achieve more quality by adding some details. When the score is done and the parts have been written, then comes the phase of rehearsing where some adjustments need to be done. This is a process that never ends. I have had some pieces done several times and at each rehearsal we discover some wrong accidentals or missing slurs. It's never completely perfect. Not even interpretation is always perfect.

BD: Is that something you really want? I assume you don't want every performance to be a repeat of the last.

KHE: No, it should be a new way of reading, of "interpretation" in the best sense of the word.

BD: Are there ever times when the performers find little brilliances in your score that you didn't know you had hidden there?

KHE: Experienced musicians do not deal so much with compositional details. They look more towards bigger formal aspects even when they find some passages very difficult to play.

BD: But if you are listening to a rehearsal or even a performance, might you hear something think, "Oh, I don't realize that I had put that in there!"

KHE: Yes, this happens. I think it is important with any music that it has some secrets that even the composer does not know.

* * * * *

BD: Are you basically pleased with the performances you've heard of your works over the years?

KHE: Generally, I am pleased.

BD: We were mentioning momentarily one the fine violinists, Irvine Arditti. Is it pleasing to you if someone of that stature elects to play one of your pieces?

KHE: Of course! In fact I've known Irvine Arditti for more that 10 years and we really became good friends, also with the whole ensemble. Every time they are in Vienna we go out for dinner, or we see each other at some festivals. They played two string quartets of mine, and then I composed a violin piece which I gave to Irvine. I was very happy to hear that he wants to play it.

BD: Is it easier or harder to write for someone who is close to you?

KHE: It's much easier, because I know how he plays and how he feels and I can put this into the music. Once I was commissioned to write a piece for a percussion player whom I didn't know. The only thing I heard was that he was not very good. So I tried to make a percussion piece which was simple to perform, but it turned out that it was horribly difficult. Perhaps it would have been easier if I had know the person before.

BD: But if you write for one set of capabilities, does that eliminate it from the capabilities of someone else?

KHE: If you write for a specific person, the piece that emerges might have a certain quality because there exists a relationship and a knowledge of each other. Other instrumentalists, however, can take this piece and make it their own.

BD: Are there enough musicians these days playing New Music?

KHE: Yes.

BD: So it is not hard to get performers interested in doing new works?

KHE: No, at least not in my case. I have lots of contacts and I am very much interested in collaboration with musicians.

BD: Are you at the point of your career that you want to be at this age?

KHE: Yes. At this age, yes.

BD: Do you have the rest of your career laid out?

KHE:

I don't know yet, but I am acknowledged in Austria as one of the young

composers, and I am about to extend this to Europe and the States. When

you're a very young composer - in your mid twenties - people will help

you a lot. Radio people are always looking for new talents. At this

time it is quite easy to get performances. But then, after three or four

years, you must really prove that your are good, and if you don't pass

the test, you are completely forgotten.

KHE:

I don't know yet, but I am acknowledged in Austria as one of the young

composers, and I am about to extend this to Europe and the States. When

you're a very young composer - in your mid twenties - people will help

you a lot. Radio people are always looking for new talents. At this

time it is quite easy to get performances. But then, after three or four

years, you must really prove that your are good, and if you don't pass

the test, you are completely forgotten.

BD: So, you've jumped over a couples of hurdles and you have made it to the next level?

KHE: Fortunately. At one time, the music curator from the Vienna Konzerthaus told me, "Karlheinz, I must tell you something. You are in a very critical situation. In Austria you are too known for someone to do something for you, and outside Austria you are completely unknown. You have to do something." I asked what I should do, and he said he didn't know. Shortly afterwards I got a telephone call from Risto Nieminen, the artistic director of IRCAM, who told me that he has seen some of my scores, that he ws interested in my music and wanted to meet me. A month later we met in Vienna, and he gave me a commission to work out at IRCAM - a piece for chamber ensemble and electronics. I started to work on it in 1992 at IRCAM for a period of one year. In connection with this commission there was a little tour with the "Nieuw Ensemble" of Amsterdam who played the premier of this piece, called Entsagung. Afterward we performed it in Rotterdam, Utrecht, Paris and finally in Vienna at the festival WIEN MODERN. During these performances the piece developed very nicely.

BD: So that's really the way to do it - to become known and then go away, and then come back?

KHE: That's theoretically the way to do it, but normally you cannot choose it yourself. You need an invitation from outside.

BD: So there is really a bit of luck involved...

KHE: It is luck, of course.

BD: But you have to be prepared when the luck comes.

KHE: Yes. And another thing was that I came in contact with Darmstadt in 1990. Friedrich Hommel invited me there as a composer-in-residence. This, however, meant something different that one might expect. Hommel invited 40 composers, and each one had the chance to present a piece in a concert and to give a lecture. You were expected to be around and discuss your work with the other composers and musicians. At this time it was a fantastic situation in Darmstadt. I went there three times and met composers of my generation from all over the world which resulted in a very nice network of contacts that still exists.

BD: Is there a competition or is there a special camaraderie amongst composers of that generation?

KHE: At the days of Hommel, I didn't feel much competition, but lots of camaraderie. I made composer friends in Britain and France. We are still in contact and see each other and look at each other's scores and discuss them. This normally happens in smaller contexts, say in Vienna among young composers, but there is also a strong competition. But if this were to happen more globally, there would be less competition. Everyone is doing his own work in his own place.

BD: There is more room in a global space. Are there too many composers around today?

KHE: No. Its okay. Quite enough.

BD: One last question: Is composing fun?

KHE: No, it's pain. It's a real pain.

BD: In the end, is it worth it?

KHE: It's worth it, absolutely. But if I could choose, I would not do it again.

BD: You'd go back to chemistry?

KHE: No. Perhaps to literature.

BD: Or be a rock star!

KHE: Yes! Hahaha... If I only could sing better! To be serious, composing is a pain, but also a lust which brings great satisfaction. So it's both. The beginning of a new piece is always painful, but once you are in it, it becomes an incredible spiritual experience.

BD: Thank you for your music so far, and thank you for coming to Chicago!

KHE: It's a pleasure for me to be here.

= = = = =

= =

- - - - - - - -

= = = = =

= =

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final hours as a classical station in February of 2001. His series of programs with interviews of musicians won for him the ASCAP/Deems Taylor Broadcast Award in 1991. Besides his on-air work, many of the conversations have been published in magazines and journals, and he now continues his radio work on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his Personal Website which has more information, photos of the radio station as well as transcripts of a few interviews. He also welcomes E-Mail and enjoys hearing from people who find his material on the internet.

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

Recorded: March 2, 1997 in Chicago

Broadcast: August 19, 2000 on WNIB

Transcription: December, 2005 by KHE

Posted on this website: August, 2006