Kenneth Gaburo,

65; Composer and Teacher

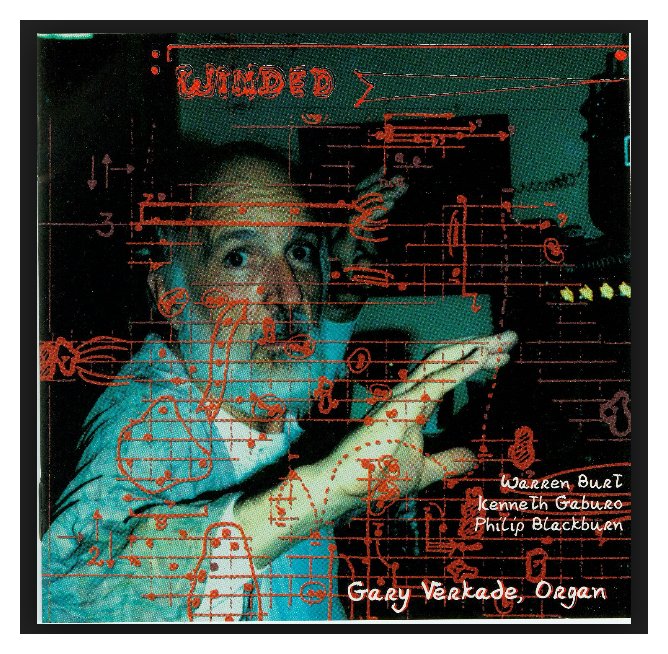

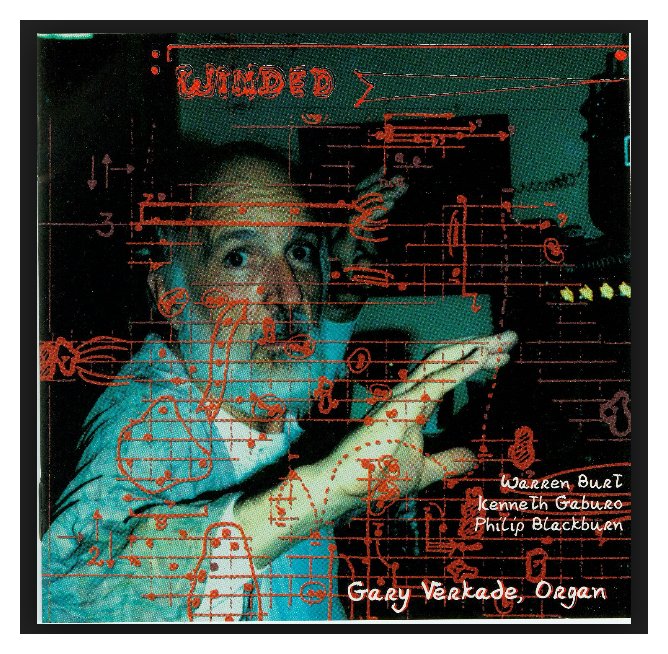

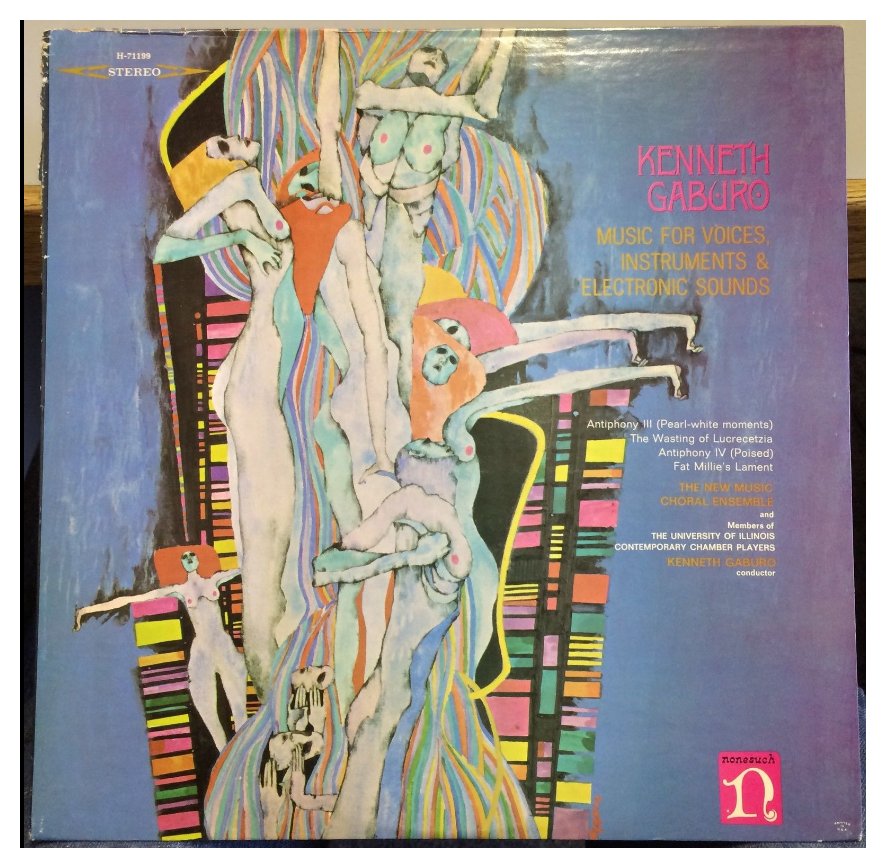

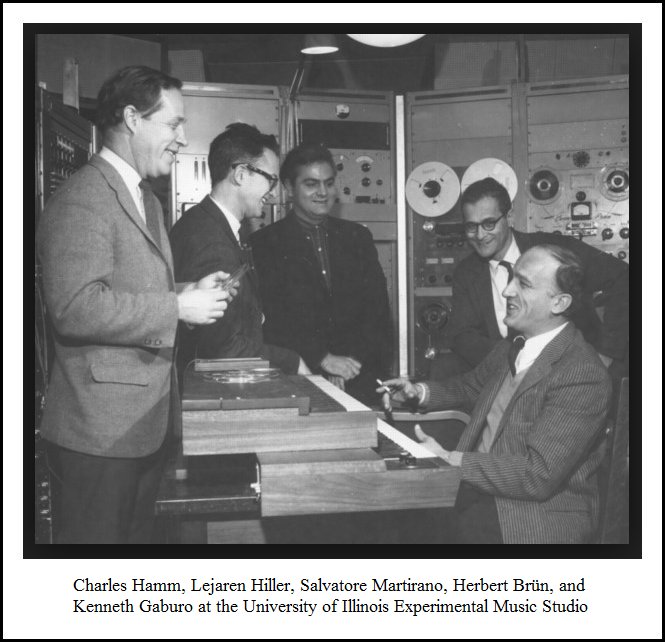

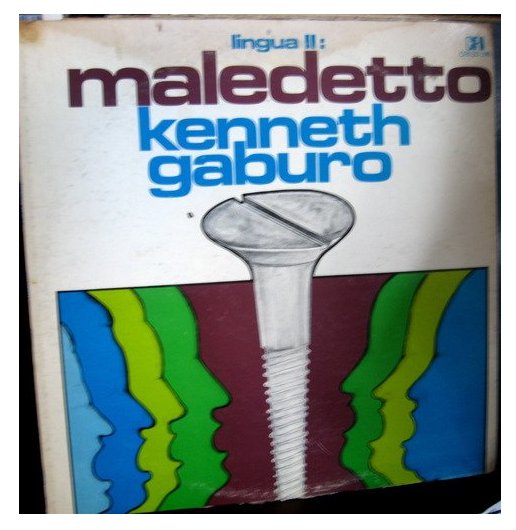

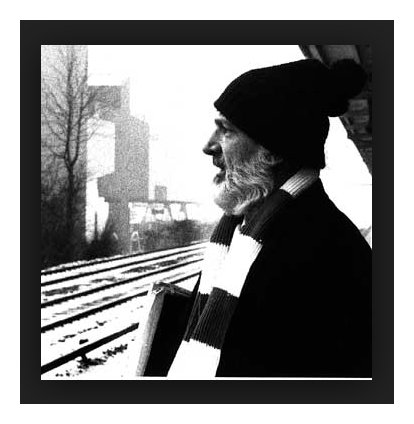

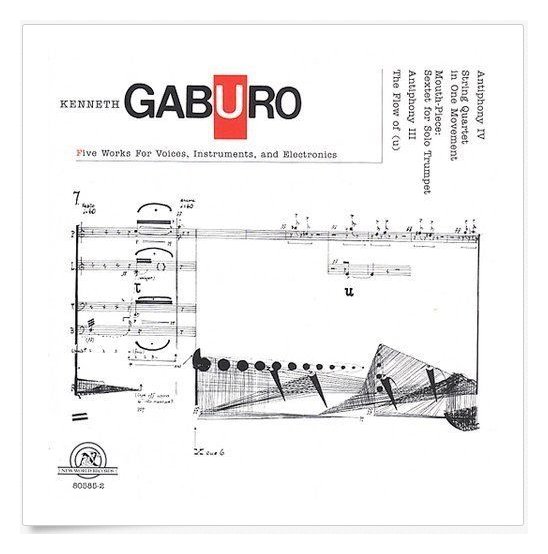

Published: January 29, 1993 in The New York Times Kenneth Gaburo, a composer, writer and teacher, died on Tuesday at his home in Iowa City, Iowa. He was 65. He died of bone cancer, said Philip Blackburn, a friend. Mr. Gaburo was a prolific composer of experimental vocal, chamber and instrumental works. He began his career as a proponent of Schoenberg's 12-tone system of composition, but later developed his own theory of "compositional linguistics," which explores the components of language as musical elements. Among his works are "On a Quiet Theme," which won the Gershwin Memorial Contest in 1954, and a set of "Antiphonies," which reflect his interest in electronic music. Mr. Gaburo was born in Somerville, N.J. He earned a master's degree from the Eastman School of Music and a doctorate from the University of Illinois, and studied in Rome on a Fulbright Scholarship. He won awards from the Rockefeller, Guggenheim, Koussevitzky and other foundations. He founded the New Music Choral Ensemble in 1960 and the Lingua Press Publishing Company in 1974, both of which focused on 20th-century experimental music. He also established the Institute of Cognitive Studies, in 1982, and taught at several colleges, including the University of California at San Diego and the University of Iowa. He is survived by his companion, Carmen Grier; two sons, Mark, of Brookings, Ore., and Kirk, of Minneapolis, and a daughter, Lia, of Los Angeles. |

KG: Not that, but what didn’t work for a long time

is that the audience these days is simply not prepared for the kind of stuff

that I’m doing. It’s not even avant-garde; it’s really radical, and

I consider it a primitive kind of thing, mainly really very fundamental,

and very basic. It’s no longer theoretical. There are theories

here and there, but it really does come from concrete things like people,

and the earth, and problems, and stuff like that. So it’s not what

an audience usually expects. It seems to me to be obvious that it’s

a theater piece. There are lights; there are dimmers. He comes on and

off stage — all the trappings that make it appear to be a theatrical piece.

There’s language; there really is a character. In this case he goes

through four changes of character.

KG: Not that, but what didn’t work for a long time

is that the audience these days is simply not prepared for the kind of stuff

that I’m doing. It’s not even avant-garde; it’s really radical, and

I consider it a primitive kind of thing, mainly really very fundamental,

and very basic. It’s no longer theoretical. There are theories

here and there, but it really does come from concrete things like people,

and the earth, and problems, and stuff like that. So it’s not what

an audience usually expects. It seems to me to be obvious that it’s

a theater piece. There are lights; there are dimmers. He comes on and

off stage — all the trappings that make it appear to be a theatrical piece.

There’s language; there really is a character. In this case he goes

through four changes of character. BD: Are you expecting the audience, then, to have

as much sophistication as you have in order to appreciate your music?

BD: Are you expecting the audience, then, to have

as much sophistication as you have in order to appreciate your music? KG: Well, this testimony project that I’ve been

doing has been more than an education. It’s been almost debilitating.

About six years ago I decided I had to take on, in my own kind of way, the

whole issue. It comes out of the whole human rights movement; it comes

out of the idea of humankind. The nuke thing is the worst act that

has been perpetrated thus far against humankind, against life itself.

So I’m concerned about life, the life of the earth, the life of all living

things, and it happens to be that taking on nuke is one part of it.

But the base is really how life is, and what we’re losing in terms of CO2

in the atmosphere, in terms of acid rain. We can’t really talk about

quality of life in the same way we could twenty or thirty years ago.

It’s not the same. I’m concerned about that, so about six years ago

I really could not be quiet about that. I’ve always been political

on specific things, but this is like the Grand One. This is it!

We’re talking about your life and my life. I started a television series

— which began in Schenectady — using a VCR to tape interviews one-on-one.

The person that I’m asking a particular question of faces the camera and

the mike, and answers the question. The face is full. It’s a

tight shot, so their face fills the entire screen. They’re asked a

question, which I’ll mention in a moment. They are also invited to

ask the question of the very next person, so what happens is very interesting.

First of all, person A answers the question verbally. Often times the

expressions on their face betray what they’re saying, but at least there

are already two languages — the whole gestural language

and the verbal language. Then when they ask the question of somebody

else, it’s very different in the way they weight the words. So this

is like three in one. I now have done 600 of those one-on-one interviews

with people from kids to old folks, to various ethnic groups, to college

students, to people who were bums, to the far right, to the far left.

I’ve had some very large difficulty with certain ethnic groups who just don’t

think that it’s their problem. They think that it’s Whitey’s problem

or something like that, so they’re difficult. But that all happened,

and it’ll be part of a large installation some time. One of the channels

on this percussion piece, which is part of this installation, has extractions

from some of these testimonies. That’s what drives Steve Schick to

go through these various psychological changes. It’s the way in which

certain people answer these questions which he personally had trouble with

when he first started the piece. He had to go through a whole bunch

of changes to really become convincing about it, because he really was one

of these people who said, like so many have in this interviewing process,

“What is one person? What can one person do? I can’t do anything

about it.” That’s a very common one, but the most common one for old

people and young, if you really probe it deep enough, is, “I don’t think

I have a future.”

KG: Well, this testimony project that I’ve been

doing has been more than an education. It’s been almost debilitating.

About six years ago I decided I had to take on, in my own kind of way, the

whole issue. It comes out of the whole human rights movement; it comes

out of the idea of humankind. The nuke thing is the worst act that

has been perpetrated thus far against humankind, against life itself.

So I’m concerned about life, the life of the earth, the life of all living

things, and it happens to be that taking on nuke is one part of it.

But the base is really how life is, and what we’re losing in terms of CO2

in the atmosphere, in terms of acid rain. We can’t really talk about

quality of life in the same way we could twenty or thirty years ago.

It’s not the same. I’m concerned about that, so about six years ago

I really could not be quiet about that. I’ve always been political

on specific things, but this is like the Grand One. This is it!

We’re talking about your life and my life. I started a television series

— which began in Schenectady — using a VCR to tape interviews one-on-one.

The person that I’m asking a particular question of faces the camera and

the mike, and answers the question. The face is full. It’s a

tight shot, so their face fills the entire screen. They’re asked a

question, which I’ll mention in a moment. They are also invited to

ask the question of the very next person, so what happens is very interesting.

First of all, person A answers the question verbally. Often times the

expressions on their face betray what they’re saying, but at least there

are already two languages — the whole gestural language

and the verbal language. Then when they ask the question of somebody

else, it’s very different in the way they weight the words. So this

is like three in one. I now have done 600 of those one-on-one interviews

with people from kids to old folks, to various ethnic groups, to college

students, to people who were bums, to the far right, to the far left.

I’ve had some very large difficulty with certain ethnic groups who just don’t

think that it’s their problem. They think that it’s Whitey’s problem

or something like that, so they’re difficult. But that all happened,

and it’ll be part of a large installation some time. One of the channels

on this percussion piece, which is part of this installation, has extractions

from some of these testimonies. That’s what drives Steve Schick to

go through these various psychological changes. It’s the way in which

certain people answer these questions which he personally had trouble with

when he first started the piece. He had to go through a whole bunch

of changes to really become convincing about it, because he really was one

of these people who said, like so many have in this interviewing process,

“What is one person? What can one person do? I can’t do anything

about it.” That’s a very common one, but the most common one for old

people and young, if you really probe it deep enough, is, “I don’t think

I have a future.” KG: Music is going every which way in a pluralistic

society, such as we are here. Since the whole business of cross-over

began five or ten years ago, serious musicians are beginning to incorporate

rock or grass root kind of stuff, bluegrass music or whatever in their pieces.

The kind of mixtures are endless and various. Also, with the availability

now of various kinds of synthesizers, with canned software programs where

you have stored wave forms — so you can get trumpet

sounds out, you can get violin sounds out — you can

play around with that stuff. So it’s becoming much more mimetic, which

is one of the grand old Aristotelian kind of complaints, that mostly the

thing that stops our imagination, the thing that stops us from growing, could

stop us from growing, is to imitate. Kids begin by imitating.

We learn by imitating. Most of the music that I hear is an imitation

of imitation of stuff that already exists. It’s not difficult at all

anymore to have a synthesizer, which you get for $2000, simulate an orchestra.

That part, I think, is really dangerous — not because

in itself it is intrinsically good or bad; it’s fun and games and stuff like

that; it’s like the videogames — but to the extent

that it nulls the imagination. We really have to have imagination to

get on with the problems of the world.

KG: Music is going every which way in a pluralistic

society, such as we are here. Since the whole business of cross-over

began five or ten years ago, serious musicians are beginning to incorporate

rock or grass root kind of stuff, bluegrass music or whatever in their pieces.

The kind of mixtures are endless and various. Also, with the availability

now of various kinds of synthesizers, with canned software programs where

you have stored wave forms — so you can get trumpet

sounds out, you can get violin sounds out — you can

play around with that stuff. So it’s becoming much more mimetic, which

is one of the grand old Aristotelian kind of complaints, that mostly the

thing that stops our imagination, the thing that stops us from growing, could

stop us from growing, is to imitate. Kids begin by imitating.

We learn by imitating. Most of the music that I hear is an imitation

of imitation of stuff that already exists. It’s not difficult at all

anymore to have a synthesizer, which you get for $2000, simulate an orchestra.

That part, I think, is really dangerous — not because

in itself it is intrinsically good or bad; it’s fun and games and stuff like

that; it’s like the videogames — but to the extent

that it nulls the imagination. We really have to have imagination to

get on with the problems of the world.  KG: There are two. There was one that I did

in 1954 that’s based on the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, The Snow Queen, and then there was one

about ten years later. I was just out of school. It’s not the

typical form. I used a lot of kids in it, and I wanted them to really

sing as if they were trained opera singers, so that was fun. But I

worked with a playwright for the first time, and so it was actually a play

that could have been staged without me. Because we were colleagues

in the same campus, it kind of grew together, so every once in a while we’d

talk about the possibility of music here or there. Eventually it became

an opera, but it was written in a way by a play, and that was my beginning

with theater. It was written for two pianos and some percussion, which

is nice. There was no orchestra. It has lots of interesting things,

but it was a very literal translation of The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen.

However, I really consider the work that began to really reflect me more

than it reflected who I’d studied with probably didn’t begin until about

’55 or ’56.

KG: There are two. There was one that I did

in 1954 that’s based on the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, The Snow Queen, and then there was one

about ten years later. I was just out of school. It’s not the

typical form. I used a lot of kids in it, and I wanted them to really

sing as if they were trained opera singers, so that was fun. But I

worked with a playwright for the first time, and so it was actually a play

that could have been staged without me. Because we were colleagues

in the same campus, it kind of grew together, so every once in a while we’d

talk about the possibility of music here or there. Eventually it became

an opera, but it was written in a way by a play, and that was my beginning

with theater. It was written for two pianos and some percussion, which

is nice. There was no orchestra. It has lots of interesting things,

but it was a very literal translation of The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen.

However, I really consider the work that began to really reflect me more

than it reflected who I’d studied with probably didn’t begin until about

’55 or ’56. KG: Yes, and that’s wonderful. It’s a growing

number. That’s not a problem but it is when you consider that a university

such as Northwestern, or probably three or four of them in this country,

graduate ten or so composers a year. It is an awful lot.

KG: Yes, and that’s wonderful. It’s a growing

number. That’s not a problem but it is when you consider that a university

such as Northwestern, or probably three or four of them in this country,

graduate ten or so composers a year. It is an awful lot.© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 9, 1987.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1991 and 1996, and on WNUR in 2002 and

2013 This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.