George Guest

Musical master who revitalised England's cathedral choirs

By John Gummer, The Guardian, Tuesday 3 December 2002

GG: No, it isn’t a requirement, but it’s obviously

a help to them if they do. They are aged seven or eight, not really

over nine. Quite a number of boys play a keyboard instrument, which

is obviously the piano, plus one other. So they play their instrument

or instruments, and then they have to do some ordinary reading — not music

sight reading, but reading of a piece of prose, because the words, for instances,

to the Psalms are very, very difficult, particularly with their archaic English,

and quite often are particularly difficult for anyone, especially to little

small boys. So a boy has to be pretty good at ordinary reading.

Then he goes off and is given an academic test by the headmaster of our Choir

School because the choristers have a great deal of singing to do and it’s

important that they don’t get behind in their general studies. So to

be a chorister at Saint John’s, a boy has to be very quick and very intelligent,

quite apart from his musical attributes. He has to have something of

a brain to get in.

GG: No, it isn’t a requirement, but it’s obviously

a help to them if they do. They are aged seven or eight, not really

over nine. Quite a number of boys play a keyboard instrument, which

is obviously the piano, plus one other. So they play their instrument

or instruments, and then they have to do some ordinary reading — not music

sight reading, but reading of a piece of prose, because the words, for instances,

to the Psalms are very, very difficult, particularly with their archaic English,

and quite often are particularly difficult for anyone, especially to little

small boys. So a boy has to be pretty good at ordinary reading.

Then he goes off and is given an academic test by the headmaster of our Choir

School because the choristers have a great deal of singing to do and it’s

important that they don’t get behind in their general studies. So to

be a chorister at Saint John’s, a boy has to be very quick and very intelligent,

quite apart from his musical attributes. He has to have something of

a brain to get in. GG: The choir has changed to a certain degree because

it’s taken all this time to build it up. Of course, public recognition

always comes some ten years after an actual reality of a standard of a choir

or of an orchestra, but now the fame of the choir does attract more and better

boys than was the case, say, thirty-five years ago. Overseas tours

also help a great deal. In the last five years we’ve covered Australia

twice, and Japan, and been to the USA on a number of occasions, as well as

Canada, Greece, Sweden, Spain, etcetera.

GG: The choir has changed to a certain degree because

it’s taken all this time to build it up. Of course, public recognition

always comes some ten years after an actual reality of a standard of a choir

or of an orchestra, but now the fame of the choir does attract more and better

boys than was the case, say, thirty-five years ago. Overseas tours

also help a great deal. In the last five years we’ve covered Australia

twice, and Japan, and been to the USA on a number of occasions, as well as

Canada, Greece, Sweden, Spain, etcetera. GG: I don’t think so. Again one’s playing

with words, I suppose. If one thinks of music as something which consists

of two elements — technique and emotion

— one of the sad and irritating businesses about being a choirmaster

is that the more you have of the one the less you have of the other.

The better the technique is and the more you work away at technique, the

less spontaneous a performance becomes and the more artificial it becomes.

On the other hand if you say, “Right, let’s have a completely emotional performance

of this. We will get lost in the emotion of the words and the meaning

of the words,” that is the time when some people tend to sing out of tune,

and points of technique go out the window. I suppose that’s the difference

between various top-class choirs — the balance and the relative percentage

between technique and emotion. You’ve got to assume a certain basic

technique, but there are many choirs that perhaps go too far in the business

of technique and become timid in their interpretation. If one really

thinks about the words, for example, of the Agnus Dei — Agnus

Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi — not Lamb of God who takes away my sins, but

the sins of the whole world, that is an extraordinary concept! Now

you cannot sing that, to my mind, in a cold, unemotional, matter-of-fact

way, although some choirs with an excess of technique would tend to do that

very thing. It all depends on whether you wish to admire a choir or

whether you wish to be moved by it. You admire technique but you’re

moved by emotion, and it’s nice to get the balance right, if possible, so

that people are pleased with the technique that they have but are also moved

by the interpretation.

GG: I don’t think so. Again one’s playing

with words, I suppose. If one thinks of music as something which consists

of two elements — technique and emotion

— one of the sad and irritating businesses about being a choirmaster

is that the more you have of the one the less you have of the other.

The better the technique is and the more you work away at technique, the

less spontaneous a performance becomes and the more artificial it becomes.

On the other hand if you say, “Right, let’s have a completely emotional performance

of this. We will get lost in the emotion of the words and the meaning

of the words,” that is the time when some people tend to sing out of tune,

and points of technique go out the window. I suppose that’s the difference

between various top-class choirs — the balance and the relative percentage

between technique and emotion. You’ve got to assume a certain basic

technique, but there are many choirs that perhaps go too far in the business

of technique and become timid in their interpretation. If one really

thinks about the words, for example, of the Agnus Dei — Agnus

Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi — not Lamb of God who takes away my sins, but

the sins of the whole world, that is an extraordinary concept! Now

you cannot sing that, to my mind, in a cold, unemotional, matter-of-fact

way, although some choirs with an excess of technique would tend to do that

very thing. It all depends on whether you wish to admire a choir or

whether you wish to be moved by it. You admire technique but you’re

moved by emotion, and it’s nice to get the balance right, if possible, so

that people are pleased with the technique that they have but are also moved

by the interpretation.

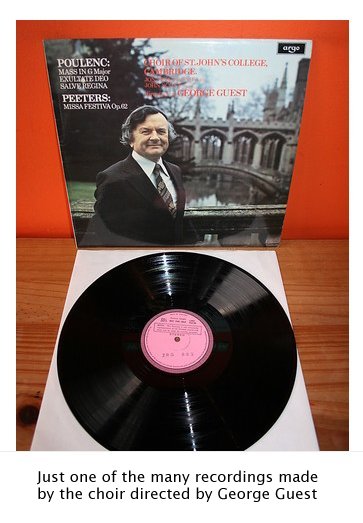

George GuestMusical master who revitalised England's cathedral choirs By John Gummer, The Guardian, Tuesday 3 December 2002 George Guest, who has died aged 78, was the pre-eminent English choral director of the 20th century, responsible in large part for the survival of the cathedral choir and the astonishing quality of its output. A man of exuberant richness - a Welsh nationalist living in Cambridge, who revolutionised the performance of French music with one of the greatest English choirs - he drew on these apparent contradictions to sustain his vast creative talent. Born in Bangor, Guest went to the city's Friars school, and was a chorister at its cathedral for two years. At the age of 11, he became a chorister at Chester Cathedral, and studied at the King's school. The severe reprimand he received for flicking paper balls across the cathedral nave during matins did not prevent his appointment as sub-organist in 1946, after four years' war service in the RAF. It was entirely fitting that Guest should start his career in the cathedral city that straddles the English and Welsh border; he possessed an innate understanding of the Anglican liturgy and the choral tradition that articulated it, and yet it was a Welsh voice that sung from his heart. Nevertheless, his tenure at Chester was short: in 1947, he went to St John's College, Cambridge, as organ scholar. Here, the choir had enjoyed 10 years of direction from two of the choral world's great luminaries, Robin Orr and Herbert Howells. When, in 1951, Orr decided to leave to concentrate on composition, he persuaded a reluctant college council to take on the young organist. Guest was to surprise and stimulate the old dons: he proved himself a charismatic teacher and intelligent musician, well liked by the clergy and a healthy influence on the college council. He immediately started laying the foundations for a professional choir. The choir school moved into new premises, while, in the rehearsal rooms, Guest set to work improving the sound and ability of the 16 boys and 14 undergraduate choristers. Down the road at King's College, Sir David Willcocks was also transforming choral standards. [Note: See my interview with Sir David Willcocks. BD.] The inevitable rivalry was seen at its best on the football pitch, when Guest and the choral scholars played a mean game, especially against the old enemy, when Guest and Willcocks made a point of marking each other. Guest's inspirational - and often ruthless - direction took the St John's College choir to a new artistic level, so much so that, in 1958, it made the first of its 60 recordings, of Mendelssohn's Hear My Prayer, for the Argo label. Guest's discography was to be unmatched by any other English choral director. Recordings were important to Guest, as he believed passionately in taking choral music outside the confines of church and chapel. Thus, he also exploited radio, on which his choir sang regularly from the mid-1950s onwards; an Ash Wednesday service including Allegri's Miserere Mei attracted particular attention. But it was the daily ritual of the college evensong that allowed Guest to develop a unique choral sound. He rejected the ethereal and breathy vocals that were prevalent in the great cathedral choirs, and were typified by the sound at King's. Instead, he developed a more gripping continental timbre - passionate, poised and direct. It was no coincidence that he came to champion the work of 19th-century and contemporary French composers, an association that culminated in two of his most celebrated discs, Duruflé's Requiem (1974) and Music By Gabriel Fauré (1975). The former elicited a warm letter of congratulation from the composer, as did Guest's recording of the Messe Solennelle of Jean Langlais, by the great, blind organist of St Clothilde, Paris. Langlais ecstatically proclaimed: "I admire everything - the style, the tempi, the voices, the organist, and the conductor. Let me tell you of my deepest gratitude and admiration." Guest's vigorous interpretations of the Haydn masses also won him much praise: indeed, prime minister Edward Heath chose the recordings made with the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields as his gift to the Pope on his visit to the Vatican in 1972. Despite the excitement of taking his choir to perform to a packed Sydney Opera House, or broadcasting to millions around the world in the Advent carol service, Guest never minded that some of his finest performances were heard by only three or four people shivering at the back of a neo-gothic chapel on a dark November evening: the choir performed for God, not for an audience. Informed by a quiet but profound spirituality, he was to direct the music for 40 years until his retirement in 1991, displaying a constant loyalty to St John's and to Cambridge, where he was university organist (1974-91) and lecturer (1956-82). Under his tuition, Stephen Cleobury of King's College, John Scott of St Paul's, David Hill of Winchester, Adrian Lucas of Worcester, and Sir David Lumsden of New College, Oxford, began the careers that have produced a golden age in the English choral tradition. Guest often remarked that you can only reach a man's head through his heart. It is not therefore surprising that, as the years went on, the chanting of the psalms became an ever more considered and thoughtful meditation. He realised that the Anglican evensong was the Church of England's greatest gift to the Christian world. It was his genius to give a unique and abiding expression to that liturgy that will live for generations to come. He is survived by his wife Nan, son David and daughter Elizabeth. · George Howell Guest, choirmaster and organist, born February 9 1924; died November 20 2002 |

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on September

3, 1986. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB

in 1989, 1994 and 1999. The transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.