BD: Kicking

and screaming?

BD: Kicking

and screaming? MH: No. I grew

up in an era that people would not understand today. There was no

television and for a long time very little radio. In that period

of slower and more gracious living, your parents had visitors.

The first thing a person would say was, “Oh, hello, how are you?

Come in. Take off your hat and coat.” Now the first thing

they do is to turn on the television. In those days, you did have

conversation. You shared ideas. You talked; you

communicated and children provided the entertainment. You began

what they called a well-rounded education. Generally somewhere

between five and six you learned to play the piano. At some point

in the evening, you would play the piano for their friends, or in my

case, I played duets with my sister. That provided a moment’s

entertainment, and then more talking, more conversation, more

communication about how their children were doing, and discussion of

the teachers, this kind of thing. One doesn’t do that

anymore. Then there were the moments when you sang hymns or home

songs, because there was no other entertainment. The people

themselves provided the entertainment.

MH: No. I grew

up in an era that people would not understand today. There was no

television and for a long time very little radio. In that period

of slower and more gracious living, your parents had visitors.

The first thing a person would say was, “Oh, hello, how are you?

Come in. Take off your hat and coat.” Now the first thing

they do is to turn on the television. In those days, you did have

conversation. You shared ideas. You talked; you

communicated and children provided the entertainment. You began

what they called a well-rounded education. Generally somewhere

between five and six you learned to play the piano. At some point

in the evening, you would play the piano for their friends, or in my

case, I played duets with my sister. That provided a moment’s

entertainment, and then more talking, more conversation, more

communication about how their children were doing, and discussion of

the teachers, this kind of thing. One doesn’t do that

anymore. Then there were the moments when you sang hymns or home

songs, because there was no other entertainment. The people

themselves provided the entertainment. BD: Did you

know even when you were singing traditional mezzo roles like Amneris

that you would eventually be singing Aïda?

BD: Did you

know even when you were singing traditional mezzo roles like Amneris

that you would eventually be singing Aïda? BD: Let me turn the

question around, then. Was there any character that you played

that was perilously close to the real Margaret Harshaw?

BD: Let me turn the

question around, then. Was there any character that you played

that was perilously close to the real Margaret Harshaw? MH: Yes,

indeed.

MH: Yes,

indeed. MH:

Technically. I think they don’t take long enough.

They all want to start at the star level and I don’t think you can

build it that fast. The old singers did not build it that fast.

MH:

Technically. I think they don’t take long enough.

They all want to start at the star level and I don’t think you can

build it that fast. The old singers did not build it that fast. MH: Oh, I

would say it would probably have to be Azucena or possibly Amneris.

MH: Oh, I

would say it would probably have to be Azucena or possibly Amneris. MH: Always

the same technique, mm-hm. Yes. When you talk about

colleagues and getting along together as an ensemble and as a family,

there’s not too much of that today, but there was in my day. When

I first went to Covent Garden, many people gave out the free advice,

“You won’t have to sing as hard here. It’s not as big as the

Met.” Of course, by this time I would say, “Oh, that’s nice to

know,” or something like that, not believing it for a minute. But

two older and much smarter and more experienced artists than I

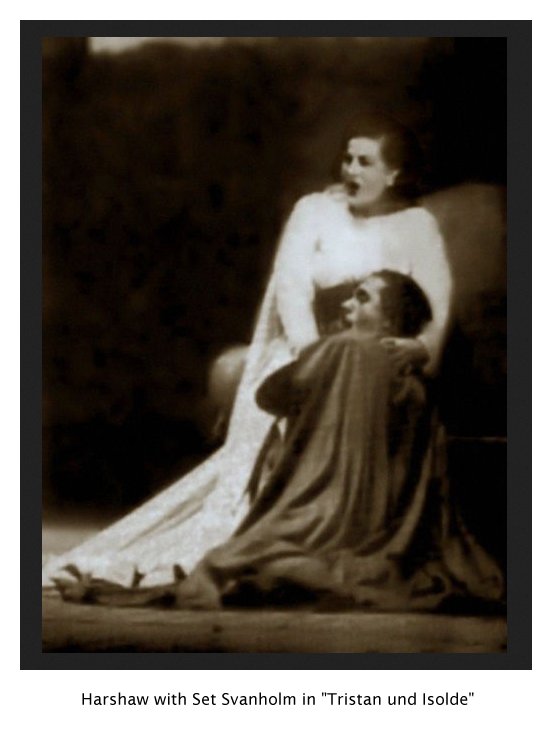

— Hans Hotter and Set Svanholm — came to me and said, “You

sing just the same in this house as you do back in the Met. Don’t

listen to these people.” I think the old Met was thirty-four

hundred seats and then they took some seats out. And as far as I

remember it was down to thirty-two hundred, and at that time Covent

Garden was about twenty-three hundred.

MH: Always

the same technique, mm-hm. Yes. When you talk about

colleagues and getting along together as an ensemble and as a family,

there’s not too much of that today, but there was in my day. When

I first went to Covent Garden, many people gave out the free advice,

“You won’t have to sing as hard here. It’s not as big as the

Met.” Of course, by this time I would say, “Oh, that’s nice to

know,” or something like that, not believing it for a minute. But

two older and much smarter and more experienced artists than I

— Hans Hotter and Set Svanholm — came to me and said, “You

sing just the same in this house as you do back in the Met. Don’t

listen to these people.” I think the old Met was thirty-four

hundred seats and then they took some seats out. And as far as I

remember it was down to thirty-two hundred, and at that time Covent

Garden was about twenty-three hundred.

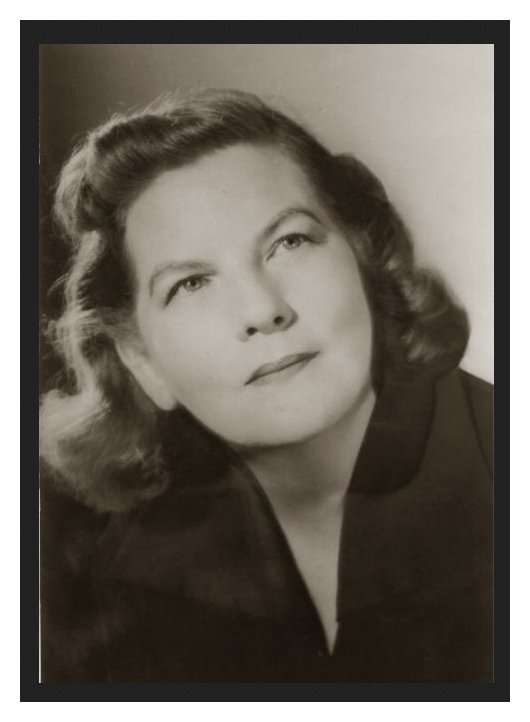

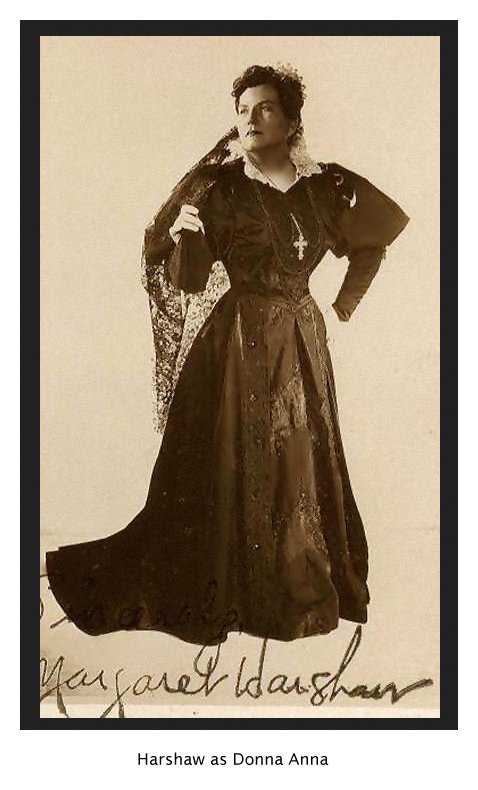

Margaret Harshaw Dies at 88; A Wagnerian Opera Singer

Ms. Harshaw sang at the Metropolitan Opera for 22 seasons, from November 1942, when she made her debut as the Second Norn in Wagner's ''Die Götterdämmerung,'' until March 1964, when she gave her final performance as Ortud in ''Lohengrin.'' Because she spent the first nine years of her Met career as a mezzo-soprano and then switched to soprano roles, she sang more Wagner roles than any other singer in the Met's history. These include 14 roles in the ''Ring'' operas, in which she began as a Rhinemaiden and eventually sang all three Brünnhildes, as well as both Senta and Mary (in the same season) in ''Die Fliegende Holländer,'' Isolde in ''Tristan und Isolde,'' Magdalene in ''Die Meistersinger,'' Kundry in ''Parsifal'' and Elisabeth and Venus in ''Tannhäuser.'' Miss Harshaw was born in Philadelphia in 1909 and began singing in church choirs as a child. From 1928 to 1932, she sang alto with the Mendelssohn Club, a chorus that performed with Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra. A series of competition victories in the early 1930's led to performances in Philadelphia, Washington and New York City, all before she enrolled at the Juilliard Graduate School to begin her formal studies with Anna Schoen-René in 1936. In March 1942, Miss Harshaw won the Metropolitan Opera's Auditions of the Air, and she began her career at the house at the start of the next season. In 1950 Rudolf Bing, the Met's general manager, was looking for a dramatic soprano to succeed Helen Traubel, particularly in Wagner roles, and persuaded Ms. Harshaw to switch to the higher range. She did so with notable success: her recordings as a soprano show her to have a clear timbre and considerable power. All told, she sang 375 performances of 39 roles in 25 works at the house and was heard in 40 of the Met's weekly live broadcasts. Her non-Wagner roles at the Met included four in Verdi works -- Amneris in ''Aïda,'' Ulrica in ''Un Ballo in Maschera,'' Mistress Quickly in ''Falstaff'' and Azucena in ''Il Trovatore'' -- as well as Donna Anna in Mozart's ''Don Giovanni,'' Gertrud in Humperdinck's ''Hansel und Gretel,'' Geneviève in Debussy's ''Pelléas et Mélisande'' and Herodias in Strauss's ''Salome.'' Ms.

Harshaw also sang at Covent Garden, Glyndebourne, the San Francisco

Opera, the Paris Opera and with companies in Philadelphia, Cincinnati,

New Orleans, San Antonio, Pittsburgh and Houston. She also made several

Latin American tours and was a soloist with many of the major American

orchestras. Roles she sang outside the Met include Dalila in

Saint-Saens's ''Samson et Dalila,'' Leonore in Beethoven's ''Fidelio''

and the title roles in Puccini's ''Turandot'' and Gluck's ''Alceste.'' |

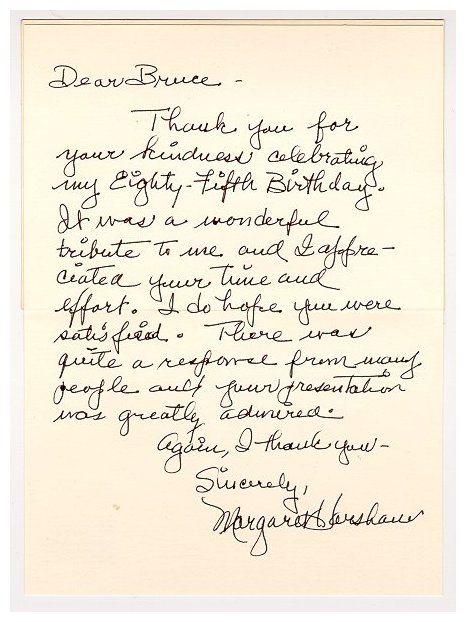

This interview was recorded at the home of Margaret Harshaw in

suburban Chicago on January 17, 1994. Portions were used (along

with recordings) on WNIB later that year and again in 1999. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award-winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.