HS: What you try to do, always, is go beyond what

you see on the paper to find the real spirit of the music which is behind

any particular notation. From the outside, it may seem that people

who play early music on historical instruments, use historical technique,

play music according to the rules set down in the Baroque or the Renaissance

periods — all these different things which seem like a kind of rigorous set

of postulates that one must follow are actually are just normally part of

the language. For instance, if you’re reading Shakespeare, does it bother

you that the sentences fall into a certain rhythm? Does it bother you

that there are subjects and verbs in the sentences? No. These

are things that are naturally part of the language, and his language is an

eloquence and reflection that no one would actually use in this particular

form today. But it’s so intimately connected with the expression and

the sort of nobility of reflection that he incorporates, that this is all

one and the same. In the best of moments, I think one should experience

no limits at all in a certain instrument or a certain period, but rather

find total freedom. What we’re trying to do is find and communicate

this total freedom, and at the same time liberate the spirit that is behind

it.

HS: What you try to do, always, is go beyond what

you see on the paper to find the real spirit of the music which is behind

any particular notation. From the outside, it may seem that people

who play early music on historical instruments, use historical technique,

play music according to the rules set down in the Baroque or the Renaissance

periods — all these different things which seem like a kind of rigorous set

of postulates that one must follow are actually are just normally part of

the language. For instance, if you’re reading Shakespeare, does it bother

you that the sentences fall into a certain rhythm? Does it bother you

that there are subjects and verbs in the sentences? No. These

are things that are naturally part of the language, and his language is an

eloquence and reflection that no one would actually use in this particular

form today. But it’s so intimately connected with the expression and

the sort of nobility of reflection that he incorporates, that this is all

one and the same. In the best of moments, I think one should experience

no limits at all in a certain instrument or a certain period, but rather

find total freedom. What we’re trying to do is find and communicate

this total freedom, and at the same time liberate the spirit that is behind

it.  HS: I have done quite a lot with different early

instruments — plucked instruments — different

types of Renaissance lutes, Renaissance guitar, vihuela, Baroque guitar,

Baroque lute, theorbo, etcetera. These are instruments almost exclusively

with double strings. Whereas the modern guitar has single strings,

on the lute you will have two strings tuned to the same note, or in the case

of the basses, a lower note and a note an octave higher. So they’re

all part of a shared esthetic, which has quite a lot of variety from country

to country, from time period to time period, and in some cases even from

one composer to another within the same geographical and chronological area.

But there are certain basic aspects of the general aesthetic which are shared

by all these different instruments. In the first case, it

is lighter construction of the instruments themselves, and being lighter

constructed, the strings themselves are finer. They are thinner than

on a modern instrument, which is heavier. So being lighter and double-strung,

the sound is more transparent, more suggestive, has more overtones and not

as much fundamental. Being lighter, they also have a more speaking

quality, not in the sense of exact vowels and consonants — although these

are elements which one can certainly use in early instruments — but also the

level of sound production that an instrument has. There is also the

speaking-ness of following the rise and fall of the voice that one has when

one uses the language in a natural way. If we say in a natural way,

“Da-da-dum, ta-ta-tum,” there’s

even a gesture involved. “Da-da-dum,”

tandem, one can imagine that hand moving in a certain way, and it’s actually

this type of gesture and this type of clarity of declamation which is intimately

related to the language of these early plucked instruments.

HS: I have done quite a lot with different early

instruments — plucked instruments — different

types of Renaissance lutes, Renaissance guitar, vihuela, Baroque guitar,

Baroque lute, theorbo, etcetera. These are instruments almost exclusively

with double strings. Whereas the modern guitar has single strings,

on the lute you will have two strings tuned to the same note, or in the case

of the basses, a lower note and a note an octave higher. So they’re

all part of a shared esthetic, which has quite a lot of variety from country

to country, from time period to time period, and in some cases even from

one composer to another within the same geographical and chronological area.

But there are certain basic aspects of the general aesthetic which are shared

by all these different instruments. In the first case, it

is lighter construction of the instruments themselves, and being lighter

constructed, the strings themselves are finer. They are thinner than

on a modern instrument, which is heavier. So being lighter and double-strung,

the sound is more transparent, more suggestive, has more overtones and not

as much fundamental. Being lighter, they also have a more speaking

quality, not in the sense of exact vowels and consonants — although these

are elements which one can certainly use in early instruments — but also the

level of sound production that an instrument has. There is also the

speaking-ness of following the rise and fall of the voice that one has when

one uses the language in a natural way. If we say in a natural way,

“Da-da-dum, ta-ta-tum,” there’s

even a gesture involved. “Da-da-dum,”

tandem, one can imagine that hand moving in a certain way, and it’s actually

this type of gesture and this type of clarity of declamation which is intimately

related to the language of these early plucked instruments. BD: Does it please you that you have made a number

of recordings, so that your legacy will not just be the concerts you have

given, but also these recordings, which will presumably last?

BD: Does it please you that you have made a number

of recordings, so that your legacy will not just be the concerts you have

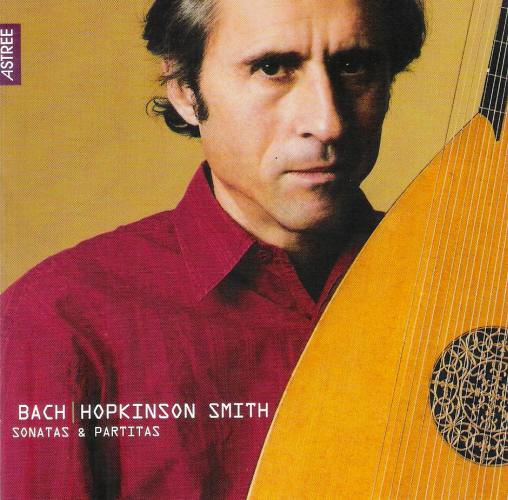

given, but also these recordings, which will presumably last? HS: I made a recording which came out at the beginning

of the Bach Year 2000 of my lute versions of The Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin

by Bach. I prefer not to use the words ‘lute transcriptions of the

originals for violin.’ I prefer to circumvent the issue by saying ‘lute

versions of pieces based on the violin versions’, because

the violin versions themselves are so often not born on the instrument themselves,

but come from some musical ideal above and beyond any instrument. In

Bach’s lifetime, some of these works were adapted for other instruments by

Bach himself, and by instrumentalists in his circle including

his son and son-in-law. So it seems a natural extension

of these works themselves to try them on the lute. There’s an interesting

anecdote, related by a contemporary of Bach, that often in the evenings he

would sit down at the clavichord and play the Sonatas and Partitas for Violin, extemporizing

the voices and harmonies which are impossible on the violin. It’s no

mystery to a lute player why he would choose the clavichord, because of all

the keyboard instruments, this is the one with the musical language closest

to the lute in terms of touch, dynamics and intimacy. The work I did

with the Sonatas and Partitas took

me several years, and I played them all in concert before I recorded them.

It was an extremely creative and gratifying project because when one is playing

so much Bach, one sort of lives artistically — and I

think a little bit in some other way — on a different

plane of existence. As Stravinsky said, “Bach

is our greatest European composer,” and I think almost

anyone would agree. There are so many instances in the Sonatas and Partitas, especially in contrapuntal

passages, where the music seems to be almost not for the violin, but against

the violin. Often the violinist is reduced to an awkwardness of bowing,

trying to play different voices at the same time with a bow primarily intended

for playing a single line on single string. Although there are other

examples of polyphonic playing on the violin from Germany in the generation

before Bach, the demands of the Sonatas

and Partitas really seem to go beyond the instrument in several cases.

Anyway, I think it’s worth listening to the more peaceful approach, the more

non-violent approach that the lute can bring to these works.

HS: I made a recording which came out at the beginning

of the Bach Year 2000 of my lute versions of The Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin

by Bach. I prefer not to use the words ‘lute transcriptions of the

originals for violin.’ I prefer to circumvent the issue by saying ‘lute

versions of pieces based on the violin versions’, because

the violin versions themselves are so often not born on the instrument themselves,

but come from some musical ideal above and beyond any instrument. In

Bach’s lifetime, some of these works were adapted for other instruments by

Bach himself, and by instrumentalists in his circle including

his son and son-in-law. So it seems a natural extension

of these works themselves to try them on the lute. There’s an interesting

anecdote, related by a contemporary of Bach, that often in the evenings he

would sit down at the clavichord and play the Sonatas and Partitas for Violin, extemporizing

the voices and harmonies which are impossible on the violin. It’s no

mystery to a lute player why he would choose the clavichord, because of all

the keyboard instruments, this is the one with the musical language closest

to the lute in terms of touch, dynamics and intimacy. The work I did

with the Sonatas and Partitas took

me several years, and I played them all in concert before I recorded them.

It was an extremely creative and gratifying project because when one is playing

so much Bach, one sort of lives artistically — and I

think a little bit in some other way — on a different

plane of existence. As Stravinsky said, “Bach

is our greatest European composer,” and I think almost

anyone would agree. There are so many instances in the Sonatas and Partitas, especially in contrapuntal

passages, where the music seems to be almost not for the violin, but against

the violin. Often the violinist is reduced to an awkwardness of bowing,

trying to play different voices at the same time with a bow primarily intended

for playing a single line on single string. Although there are other

examples of polyphonic playing on the violin from Germany in the generation

before Bach, the demands of the Sonatas

and Partitas really seem to go beyond the instrument in several cases.

Anyway, I think it’s worth listening to the more peaceful approach, the more

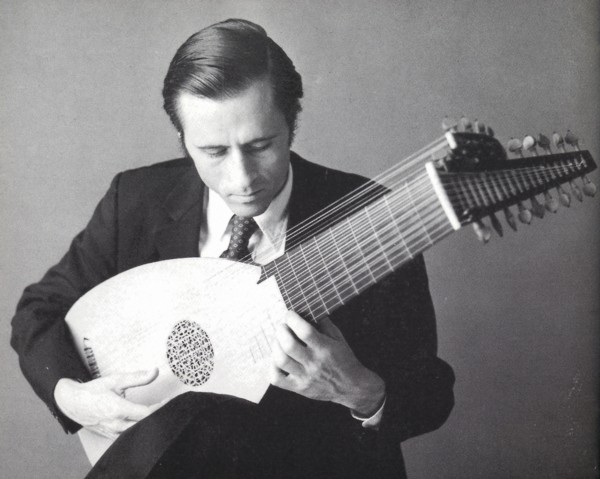

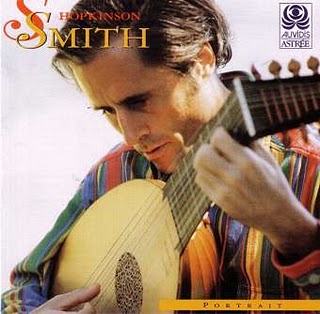

non-violent approach that the lute can bring to these works. | The American lutenist, Hopkinson Smith,

began as a teenager he began to study the classical guitar and in his early

20's, he became acquainted with the lute which he started to learn by himself.

He majored in musicology at Harvard and graduated with honors in 1972. In 1973, Hopkinson Smith came to Europe to devote himself to the lute in earnest. He worked in Catalonia with Emilio Pujol, a profound pedagogue in the 19th century tradition who instilled in him a sense for higher artistic values, and in Switzerland with Eugen Dombois whose sense of happy organic unity between performer, instrument and historic period has had a lasting effect on him. From the mid 1970's, he was involved in various ensemble projects including the founding of the ensemble Hesperion XX and a ten-year collaboration with Jordi Savall. This collaboration led to important experiences in chamber music which were a creative complement to his work as a soloist. Since the mid 1980's, Hopkinson Smith has focused principally on solo music for early plucked instruments. These include the vihuela, Renaissance lute, theorbo, Renaissance and Baroque guitars and the Baroque lute. In so doing has delved ever deeper into rediscovering the legendary powers of persuasion of the lute in former times: its noble eloquence and rhetorical clarity arising not only from great beauty and purity of sound, but above all from an infinite variety of nuances of touch and color of tone that gives its voice the immediacy of the spoken word. Smith's playing is frequently noted by reviewers for its tastefulness and expertise, while also being warm and always consciously expressive no matter what type of piece he is playing. With his recitals and a series of over 20 solo recordings, Hopkinson Smith continues to rediscover and bring to life works that are among the most expressive and intimate in the entire domain of early music. These include Renaissance fantasies, variations and dances of the vihuela and lute repertoires (Milan, Narváez, Mudarra, de Rippe), the avant garde contrasts of early Baroque Toccatas (Kapsberger), the super-refined 17th century French lutenists (Denis Gaultier, Vieux Gaultier, Mouton, Dufaut, Gallot, de Visée), Spanish music for S-course guitar rising directly from the popular tradition (Sanz) and from court circles (Guerau) and the flowering of the lute in central Europe in the high baroque both as a solo instrument (Sylvius Weiss), and in concertos with string accompaniment (Johann Friedrich Fasch, Hagen, Haydn, and Kohaut). Projects involving the music of J.S. Bach have been a recurring theme for Hopkinson Smith. His recording of the official lute works has been complemented by his own lute arrangements of the cello Suites (1992) and of the Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin (1999). The latter recording has been called 'arguably the best you can buy of these works - on any instrument' by Gramophone magazine. Internationally recognized as a leading personality in the field of early music and one of the world's great lutenists, Hopkinson Smith gives concerts and master-classes throughout Western and Eastern Europe, Asia, Australia and North and South America. He currently lives in Basel, Switzerland, where he teaches at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. |

This interview was recorded in Evanston, IL, on April 16, 2003. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNUR soon thereafter. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.