Conversation Piece:

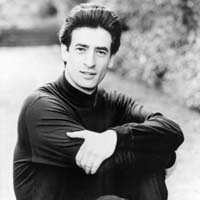

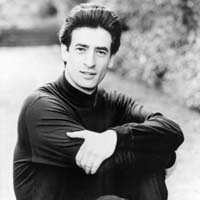

Conductor YAKOV KREIZBERG

By Bruce Duffie

Yakov Kreizberg was born in 1959 in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad),

Russia, and started taking piano lessons at the age of five.  He

studied conducting privately with Ilya A. Musin, (the renowned Professor

of Conducting from the St. Petersburg Conservatory), before emigrating

to the United States in 1976. There he was awarded conducting fellowships

at Tanglewood with Leonard Bernstein, Seiji Ozawa and Erich Leinsdorf,

and at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute, where he was invited back

as assistant to Michael Tilson Thomas.

He

studied conducting privately with Ilya A. Musin, (the renowned Professor

of Conducting from the St. Petersburg Conservatory), before emigrating

to the United States in 1976. There he was awarded conducting fellowships

at Tanglewood with Leonard Bernstein, Seiji Ozawa and Erich Leinsdorf,

and at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute, where he was invited back

as assistant to Michael Tilson Thomas.

Rapidly establishing a strong reputation in the United States, Kreizberg

won the Eugene Ormandy prize from the University of Michigan and in 1986

won first prize in the Leopold Stokowski Conducting Competition in New

York. From 1985 to 1988 he was Music Director of Mannes College Orchestra

in New York and from 1988 to 1994 he held a highly successful tenure as

General Music Director of Krefeld - Mönchengladbach Opera House and

the Niederrheinischer Sinfoniker. He then went to the Bournemouth

Symphony Orchestra, becoming Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor,

a post he relinquished in 2000. He has also been General Music Director

of the Komische Oper Berlin and Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of

the Jeunesses Musicales (World Youth Orchestra).

His debut at the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, when he conducted Jenufa,

received great critical acclaim. The Sunday Times called it, "One

of the most sensational debuts here in living memory," and he was asked

to return for the 1995 Festival to conduct Don Giovanni (which is

available on video) and in 1998 to conduct Katya Kabanová.

In the 1995-96 season, Kreizberg came to Chicago to lead Lyric Opera's

production of Don Giovanni. In between performances, I had

the great pleasure of chatting with this fine musician, and here is much

of what we talked about . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: I'd like to talk mostly about music and not

much about politics.

Yakov Kreizberg: Lovely. However, politics sometimes

have to be talked about as well. Politics as related to art and culture.

BD: OK, should politics invade the world of art and culture?

YK: (takes a deep breath) I'm afraid they do, don't they.

Let's face it, we're dependent on them.

BD: Is there any way of getting away from them?

YK: If subsidies are cut all together. We are nearly

to that point. Arts organizations in this country are suffering badly.

When good-quality middle-budget companies or orchestras are on the verge

of extinction or have gone under, it's a very dangerous situation, is it

not? We're seeing it in this country, and now it's becoming a global

problem. I'm very familiar with that because I've been living in

Europe for nearly eight years, and until now it's been on a silver plate

compared to the United States. But things are changing dramatically

now.

BD: You're Music Director in a couple of places. Would

your artistic decisions be very much different if you didn't have to worry

about financial support?

YK: Yes.

BD: How so?

YK: (ponders a moment) I think we would all have a lot more

courage to do projects which take courage to do, to perform works which

take courage to perform because you know that audiences around the world

are basically conservative. There are exceptions, but even in the

very big cities and cultural centers, audiences tend to be quite conservative.

BD: Now are you talking about the music alone, or also the

story content in operas?

YK: I'm talking about symphony and opera doing contemporary

music, contemporary art. A perfect example of that would be the music

of Janácek, and he is not even ‘contemporary.' In the minds

of many people around the world, he's probably someone who's still alive

today because they don't know the name.

BD: So that's off-putting?

YK: So that means it's probably something horribly modern,

and therefore we shouldn't risk it. It might be awful. Now

remember, we're talking here about some of the most beautiful music ever

written, and I think some of the most exciting opera in the entire literature.

It's music that is completely original. It's like no other composed

prior to that point. If we talk about people like Beethoven, we know

where he comes from, we know where his roots are and where he learned.

Even though he developed his own style, we also know who he learned from.

He didn't just appear on the face of the Earth. Janácek just

appeared on the face of the Earth, literally. His musical style and

his treatment of the language to which he set his music is like no other

in history. There is no precedent for that kind of writing.

When you have that sort of example, it's terribly exciting and terribly

interesting. He is so great and so innovative and so full of fantasy

because he was not constrained by any kinds of set forms before him.

He was literally searching for completely new ways. What we have

is an extraordinary composer who was like nothing before him and like nothing

after him. He is really in a school of his own, yet all over the

world today, even with educated audiences, it is very very hard to get

the audiences to come to hear his pieces. Perhaps Katya Kabanová

and Jenufa, which are the best-known of his operas, have somewhat

of a better time.

BD: And maybe Sinfonietta in the concert hall.

YK: Yes, because people have heard of it and it's been recorded

a number of times by important orchestras.

BD: Then, because you have this respect for him, do you jump

at the chance to do operas by Janácek?

YK: I do very much. I'm a great fan and have had marvelous

experiences performing some of his operas under the best conditions in

the world, namely at the Glyndebourne Festival in England. Working

with marvelous directors and first-rate orchestras and the very best singers

that there are for this repertoire and having lots and lots and lots of

rehearsal time, I've been a bit spoiled. But it's been a great experience

doing this sort of thing. Then I come to Chicago and you're doing

Makropoulos

Case, which is lesser-known! It's not easy to get the audiences

to come, but once they do come and see, they're satisfied. But it's

getting them to come.

BD: We have the advantage here because most of the seats are

sold on subscription. People get a package of eight operas and that's

one of them.

YK: You have the advantage. Nonetheless, the company

is not as happy because it's not completely sold out, which is the case

with Don Giovanni, which everybody knows and loves and there is

no risk involved. You know exactly what you are going to see.

When we talk about Janácek, we are not talking about anything that

is in any way new. So what happens to the composers whom nobody knows

or whom people have only heard of and don't know their music, their

symphonies, chamber music, operas? They don't go. Only people

who like to take a risk, people who like to be challenged by new things.

People who are interested in modern art, paintings, sculpture, architecture.

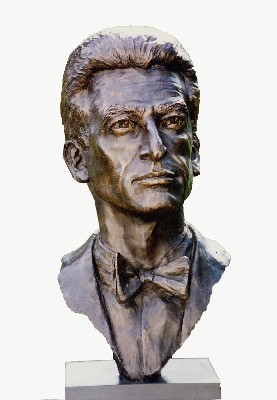

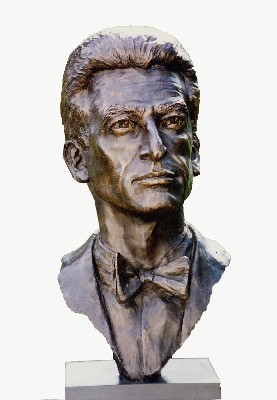

Bronze bust of Jakov Kreizberg by the British

artist Sally Derrick.

Proceeds from the sale of this piece went to the

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Endowment Trust

BD: Is it right to ask the tired businessman who's been beating

his brains out for 10 hours at the office to come to the opera house and

be challenged? Or should he come to the opera house and relax?

YK: I think an opera experience or a concert experience is

not just about relaxing. I think that people who really enjoy classical

music - whether it's of the past or contemporary - don't go to a concert

or the opera merely to relax. Of course, certain such outings are

going to have that aspect attached to them, but that is not the reason

why people are going. Our job is not to make them relaxed.

Our job is to make the challenged. It's to make them interested.

It's to make them excited about what they are seeing and hearing.

It's to make them think about what they're seeing and hearing. It's

not just to give them a beautiful voice on the stage. If they just

want the beautiful voice, they'll buy a CD and listen to it in the privacy

of their own living room at the time that they want to listen to it - not

at 7:30 in the evening with thousands of other people. They can turn

off the recording when they want to and do something else or have a snack.

If they really just want to relax, they will go to bed or turn on the TV

or whatever it is that makes them relaxed. People go to the theater

for the whole package, which means all of those things - interesting staging,

not just voices but drama and music that go together in the positive way.

It all works together, not against itself, to form the theatrical and dramatic

experience which is challenging. It will, therefore, be a much more

satisfying experience than just feeling relaxed.

* * *

* *

BD: You've been talking about your job in presenting these

works. Let me go one step further - what is the purpose of music?

YK: A universal question, is it not? The purpose of

music is so multi-faceted that it cannot be answered with a simple statement.

A purpose is to do all those things. It is essentially to make a

person a better human being, and a better human being doesn't mean just

better than a neighbor, it means a more complete person. Music brings

emotion in us. Music brings feelings which we otherwise don't get

to experience in our life, or which are often shut off because of necessity.

We have a job which we do from 9 to 5 or whatever the hours are.

Music allows us to really find our inner self, to be free to search for

those things that we normally don't have the opportunity or the time to

search for. It opens up many, many doors within us. It opens

the doors to our soul, to our feelings, to humanity as a whole. It

can do many different things, but most importantly it uplifts.

BD: Is it at all a problem for you, as a musician, to have

your 9 to 5 job be in this musical realm?

YK: Fortunately for those of us who are musicians, we don't

have 9 to 5 jobs. For me, for example, as the Chief Conductor of

an opera house, my job starts most days at approximately 8:15 in the morning,

which is when I arrive at my office, and ends between 10:30 and 11 in the

evening, when I finish a performance. In between those hours, there's

going to be numerous rehearsals, very likely a performance, probably a

number of meetings, perhaps interviews, many other things.....

BD: In the end, is it all worth it?

YK: Absolutely. If it weren't, would I be doing it?

Let's face it, I was born in the former Soviet Union and I grew up there

and I didn't leave the country until I was sixteen years old.

BD: So it was all your formative years.

YK: Yes. Particularly in that society, which puts music

and culture on a pedestal, musicians and artists in general are very much

respected. When people go to a concert, they listen with reverence.

All musicians who have performed in Russia in the earlier days have always

enjoyed it. They didn't earn any fees and it didn't help their careers,

but they had the best audiences in the world because those audiences particularly

were appreciative of going to performance because they had such a hard

life, such a miserable existence. Going to a concert was their way

to fulfill their dreams, their fantasies, to put that system out of their

life for two hours and experience beautiful music. This was something

which was very, very important to those people. They would not have

traded that experience for anything else. For someone who grew up

in that system, you knew that if you chose to be a musician, you did not

choose it because it was going to give you fame or earn you astronomic

amounts of money. In that society, it simply didn't. Most musicians

were poor and they didn't have any fame. Except for the very few

fortunate, privileged ones, you were not allowed to travel abroad.

So, if you wanted to be a conductor, you would most likely end up in some

very small provincial town, somewhere far away from where you family was

or far away from where you grew up. It might be in Ukraine or Siberia

or who knows where, because that was your assignment. That was where

you were sent, and that was that. You didn't apply for another job.

You didn't have choices.

BD: Is that why you left?

YK: Amongst many other things, but the point I'm trying to

make is that I think most of us who chose this profession chose it for

the right reasons. We chose it really for the love of music and for

the conviction that it is something we wanted to do for the rest of our

lives because we passionately believed that it is beautiful and that it

is important.

BD: Have you returned to Russia since the breakup of the Soviet

Union?

YK: Never. I have never been back, and it is now nearly

twenty years. Frankly, I don't really have time to go as a visitor

because my schedule is simply very, very difficult. I rarely am able

to get away for anything at all.

BD: I was going to ask if you leave enough time in your schedule

for rest for yourself, and for study of new scores.

YK: For rest for myself, much too little. It's really

not a good situation, and it's probably true for a lot of people, particularly

at the young age where I am. We all think we are invincible and we

have all the energy in the world. We are not invincible and we don't

have all the energy in the world, and it's a very dangerous situation because

so many young people burn out and start losing passion for music and for

the profession. They simply get tired. It is very, very important

to take time off. The reason why it is hard for us to do is because

there are always a lot of interesting and exciting offers and opportunities

(if you're good and if you're liked), and if you are in a position as a

Chief Conductor of a major European opera house, they function year-round.

They're only closed for six weeks in the summer and they do nearly 300

performances a year. That means that if you want to really be a part

of the organization and be effective and take care of things, you must

be there at least five or six months a year. That's a lot these days.

Most Chief Conductors are only there for so many weeks. Three months

is considered a good amount of time. I spend five to six months in

Berlin and I do it because I deeply believe it is necessary and it's very,

very important. It's bringing real results. Also I do it because

I love what I'm doing and I love the company. I'm very, very happy

to be there and be in that city where culture is deeply appreciated, where

audiences are so much younger.

BD: Since the wall has come down, have you noticed a different

kind of melding of East and West cultures?

YK: Yes. Absolutely. It's a melding, and at the

same time there is still a little bit of a wall left in the German mentality.

There is still a kind of separation between the East and the West.

The salaries have not yet been completely evened out. The level in

the East is still about 25% lower on the average, and the unemployment

is much, much greater because they've had to switch to the new system.

That means a lot of factories have closed and a lot of jobs are gone, and

a lot of people have not been able to find a job, or they have to be re-trained,

and that takes time. The old East German companies were inefficient

and were so heavily subsidized as to be ridiculous. Now they have

to take care of themselves, and those that are not efficient go under.

It's simply the way of the world. It's the free market. There's

been a lot of hardship and there is also, in a way, a different mentality.

East Germany and West Germany have been such for nearly 50 years, and the

new generations grew up on different sides of the wall, learning different

values, different mentality, different ways of doing things, different

views of life. In a way, they're not related to each other any more.

They are Germans, but they are two different cultures.

BD: They've lost this half-century.

YK: That's right.

* * *

* *

BD: You're Music Director at the Komische Oper in Berlin,

which is Walter Felsenstein's old house. Do you feel a great sense

of history being there?

YK: Absolutely. This is why I'm so happy. It's

a theater which is one-of-a-kind in all of the world. It's a theater

with such a tremendous staging-tradition. Harry Kupfer, who is a

disciple of Felsenstein, and who is now the Chief Stage Director for the

last twelve or thirteen years, is my partner with whom I do all of my new

productions. He is a real "Stage Director," not just somebody who

gives singers an instruction to go left or to right. It's so much

more than that. It's a complete experience. It's a complete

Musical Theater. After doing that, it's so hard for me to do operas

anywhere else because it's nearly always disappointing. It's no longer

a complete package, and I'm spoiled because I like that complete package.

For an audience member, this is what opera should be all about - not just

the voice and not just staging, but both.

BD: You should endeavor to have yourself and Kupfer hired

as a team to go around the world as guests in other houses.

YK: The problem with that is because I do so much opera there

in Berlin, it leaves me so little time to guest-conduct altogether.

So when I do guest-conduct, it's mostly concerts. When I do an opera

somewhere, it normally takes two to three months of being in that other

place. I just don't have that kind of time. Coming to Chicago

and doing Don Giovanni is an exception for me. I'm happy about

that restriction because I'd rather have my team and plenty of rehearsal

time. The other exception for me is the Glyndebourne Festival because

the working conditions are simply the best in the world. We have

seven or eight weeks for staging and we have the London Philharmonic.

The company really cares what goes on. You're in the middle of a

beautiful countryside with no time to be interested in anything else and

the only close place to go is London. So you're likely to spend all

your time in Glyndebourne thinking about your work and doing it.

It's a marvelous setting. Very beautiful. So I do like to go

there, but other than that, I rarely allow myself to do opera anywhere

else.

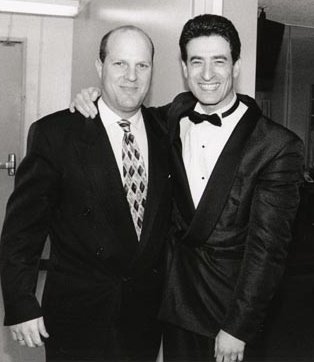

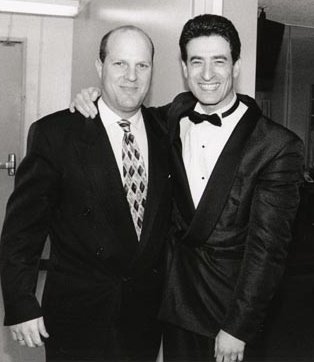

Kreizberg (right) with Evan Wilson,

principal violist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic

BD: Let me ask a dangerous question - is there such a thing

as a perfect performance?

YK: Frankly I don't know what a ‘perfect performance' would

be. Is there such a thing as ‘objectively perfect?' Perfect

for me might be seen as imperfect to you. Perfection is something

that can only be in your mind. You can determine what your goal is

and you can strive to achieve that goal. If you have high expectations

and if you work hard and want a lot, you will come closer to that goal,

but you're not likely to completely fulfill it. In a way that might

be a good thing. It's also very frustrating because I am nearly never

satisfied. I'm very, very critical of myself in the first place,

as well as orchestras or singers that I work with. I demand a lot

and I want a lot, and many people call me a perfectionist, but that simply

means that I will go as far as I can, and push people 150% of what I think

they can do. In the end, it doesn't mean that the result is going

to be perfect. It's only a question of how close you can get to your

dream. The more you expect, the further away you'll be from that

goal. It's going to be hard to reach such high goals.

BD: But you're always striving for them.

YK: Yes. It's a good thing because you're always motivated

to do more and to be better. At the same time, it's also frustrating,

particularly being a conductor. In a way you learn that the more

you know, the less you know. It's maddening. Sometimes it takes

a very, very long time to find an answer to a question that's been nagging

you. It can be years, and the moment you have solved it, you discover

two other problems to which you have absolutely no solution. You

live and work in the knowledge that no matter how long you live - and conductors

can live to be very old and not stop working - you have no chance to solve

all those problems or answer all those questions.

BD: Is it good to know that you will solve some problems,

even though you'll wind up with more, but different ones?

YK: Yeah. It's very, very satisfying when you finally

learn something new and solve a particular problem. You feel you've

accomplished something. There is nobody who can learn everything

there is to know, no matter who you are. Not Karajan, not Bernstein,

not whoever. And they knew it. They lived with the knowledge

that they would never know everything.

BD: Yet, as the conductor, you're expected to know everything

about this piece.

YK: You're expected to know more than the people you're working

with. If you don't, you have no business being there.

BD: Do you usually know more than the cast you're working

with?

YK: I certainly hope so. It's not really a question

for me to answer, but rather for the people who are working with me - the

orchestra or the director or the singers. I would certainly hope

that that is the case. I study my works very, very hard. I

know the scores backwards and forwards. The rest is all a question

of knowledge and talent and ability. We all have it to various degrees.

* * *

* *

BD: When you're putting a production together, do you get

all of your work done in the rehearsals so that each performance is approximately

the same, or do you leave something for the spark of the evening?

YK: Karajan was once asked, "Do you get nervous or worried

before a performance?" And he said, "Why should I? We have

done all the rehearsals and all the preparation. Everybody knows

their job. What can possibly happen?" I think that answer is

somewhat simplistic because a lot can still happen, and, in fact, a lot

does happen and should happen. There are different things that can

happen, both positive and negative. After all, a live performance

is not a recording. Very often, when critics go to performance with

the need to write something about it, they will listen to a recording and

they'll arrive at the theater with a preconceived notion based on what

they heard, and they'll compare the performance with the recording.

The less familiar they are with the repertoire they're going to hear, the

more they will be influenced by the record. The sad thing about that

is that all performing is subjective. There is no such thing as an

objective interpretation. There is no such thing as ‘authentic' interpretation,

either. We have entered an era where it is fashionable to think that

certain performances, because they're conducted by certain conductors or

sung by certain singers or played by certain orchestras, are ‘authentic.'

But to come back to your question, everything is done in rehearsal to a

point. You have a musical and staging concept and hopefully they

function harmoniously with each other. You know the end goal.

You know the spirit you want to create, you know the tempo relationships

and the pacing and such. All of that has to be taken care of in the

rehearsals. But the performance is never going to be just a repetition

of what you have prepared. Obviously, the better the preparation,

the more secure and comfortable everyone is going to be because they understand

their job better. And when they understand their job better, they

are more free inside to make the kind of input and creativity which can

only take place by first having exercised discipline in the preparation.

Creativity cannot come out of chaos. All that comes out of chaos

is chaos. Creativity that comes out of disciplined preparation can

bring those dimensions that we are talking about. In each performance,

there are going to be different ones. There are not going to be any

two performances that are exactly the same, nor should there be.

Each time you are recreating a work, which, until the singer sings his

first note or the orchestra plays the opening phrase, is nothing more than

instructions on a printed page. So yes, there should be creativity

in every performance.

BD: How slavishly do you adhere to every mark on that page?

YK: That depends on how passionately I believe that the instruction

given to me is in the best interest of the music. I have done a lot

of contemporary music, including a number of first performances by living

composers, such as Aribert Reimann, and Siegfried Matthus (who are two

of Germany's leading composers), and Berhold Goldschmidt. I know

that the piece of music will only live if it is recreated by a creative

mind. There is no such thing as an authentic interpretation of any

of those pieces. Having done them with the composers present and

having often asked whether what I was doing was right or not, or getting

criticism from them of what I was doing, I sometimes did things completely

different from what was notated. I discussed with them why I was

doing it and they often agreed, or suggested that my feelings were correct

and it was better that way. This led me to believe that one mustn't

simply follow blindly every single marking. The notes, yes.

But tempo indications and dynamics and things like that are suggestions

which the composer at the time passionately believes are in the best interest

of the performance. But when preparing it, there can be other ideas

and considerations.

BD: So these ‘new' ideas are right for you in that production,

but would not be right for another conductor in another place?

YK: Perhaps another conductor has a different temperament.

These things all hang together and depend on your concept. A work

only comes alive by being seen through somebody's eyes. When you

and I look at a modern painting, I will see something different in it than

you will. The greater the painting, the more you and I will see in

it. The same goes for a piece of music. These composers will

often say to me their compositions come alive when you do them, and each

conductor should have his input. That's what makes them interesting.

If everyone does them exactly the same way, our world becomes stagnant.

People must see them in different light. I also know that from personal

experience because I've done some composing myself. I don't claim

to be talented in composition, and in fact gave up composing when I realized

I didn't have enough talent for it. But I spent several years in

my teens studying composition in Russia, and several of the works were

performed.

BD: So that gives you more of an understanding of the composer.

YK: Absolutely. It was an invaluable experience because

I understand how the work is put together.

BD: Is this some advice you have for young conductors - to

do a little composing?

YK: I think it would not hurt anybody to learn how the creative

process takes place, how the work comes into being on the paper, and then,

if possible, seeing it performed, seeing it created, being there for the

rehearsals. You learn more about your own composition, you learn

that what you wrote down might not necessarily be the best suggestion.

Perhaps the performer, who is creative, might find a better way of expressing

your music than you yourself thought possible. You will learn a lot

from it. I also have listened to other composers performing their

works, whether as conductors or as instrumentalists. When you do

that, you see how much they do differently from what they themselves put

down. That's what the creative process is all about. Hearing

the music in your head and writing it down is different from conducting

an orchestra or playing that same piece on an instrument. It feels

different. When I conduct a work, I'm more likely to conduct it in

a different tempo than when I hear it in my head. In the case of

performing the work, you have a physical connection to the music.

You have a physical connection to the sound. For the same reason,

when I play the piano, I will play certain compositions differently than

when I hear them in my own head. There is a physical relation to

the instrument and it changes things.

BD: I wonder if that will change in you as you get older and

get more experienced. Perhaps you will have more of that physical

feeling in your head when you are alone.

YK: It probably will, and probably has over the years.

But I think there will always be a difference between when you are just

thinking of it and when you are physically creating the sound. The

physical factor is simply that important.

* * *

* *

BD: Are you at the point in your career that you want to be

right now?

YK: (ponders a bit) I have never thought of career-movements

corresponding with a certain age. I have never had a sort of goal

to be at a certain place by a certain age. I'm sure there are people

who think about it that way. "When I am forty, I want to be Chief

Conductor of So-and-So Symphony," or whatever. I was never really

interested in that sort of thing. As I said earlier, I decided to

become a musician, or rather it was decided for me when I was five years

old. My parents took me to a teacher who said I must study music,

and that was that.

BD: Did you ever regret that?

YK: Never! How can I regret it? It's the most

beautiful thing I could ever do. (Laughing) It's probably the only

thing I could ever do! But I've never thought in terms of ‘career'

or in terms of ‘accomplishments.'  Obviously,

I always wanted to grow and be better, because you always feel limited

by your own knowledge. I was never very keen to make a quick splash.

It would have been relatively easy because if you are young and if you

are talented, it's really not all that difficult if you're in the right

place at the right time. You can jump in for somebody who is ill,

or go and conduct one or two repertoire performances in a European opera

house, put them on your resume and progress that way. I didn't feel

that was right for me. I felt that I was a slow learner, even though

to most people I was an incredibly fast learner. You could put a

score in front of me and I could play it for you on the piano. I

learned that when I was a teenager. I could sight-read anything.

I used to accompany singers. When I came to New York at age sixteen,

I used to play in all the voice studios. I made my living that way

and put myself through college.

Obviously,

I always wanted to grow and be better, because you always feel limited

by your own knowledge. I was never very keen to make a quick splash.

It would have been relatively easy because if you are young and if you

are talented, it's really not all that difficult if you're in the right

place at the right time. You can jump in for somebody who is ill,

or go and conduct one or two repertoire performances in a European opera

house, put them on your resume and progress that way. I didn't feel

that was right for me. I felt that I was a slow learner, even though

to most people I was an incredibly fast learner. You could put a

score in front of me and I could play it for you on the piano. I

learned that when I was a teenager. I could sight-read anything.

I used to accompany singers. When I came to New York at age sixteen,

I used to play in all the voice studios. I made my living that way

and put myself through college.

BD: Did you learn from those voice teachers almost as much

as the singers did?

YK: Absolutely. In a way, that's why opera was such

a natural thing for me to do because I had a feeling for voice and a feeling

for singers. I did chamber music, too, but the voice was more.

Things were easy for me, but for what I wanted for my musical ambition,

I felt that I was slow. I felt that I needed a lot of time, and I

didn't want to make a quick ‘career' jumping in for sick conductors and

doing a few routine performances (with no rehearsal) in the opera where

the orchestra wouldn't remember me at all the next day. I decided

that the right way for me was the slow way, where I would learn how an

opera house is put together, how it works - administrative things - learn

the repertoire slowly, to do a lot of performances in the provinces, which

is what nearly all the great conductors of the past had done.

BD: So now you're Chief Conductor and you're putting all this

knowledge and experience to work.

YK: Yes, but before I was Chief Conductor in Berlin, I was

Chief Conductor of Krefeld - Mönchengladbach, a middle-size provincial

opera house, a very good "B" theater. Karajan had spent several years

in Ulm, which was much smaller, where he conducted all the operas and operettas

- the good ones as well as the trashiest ones because he felt that that

was the most difficult thing a conductor could do. And he did that

for the experience.

BD: So it's easier to make music out of Mozart than it is

out of a piece of trash?

YK: Oh believe me it's hard enough to make music out of Mozart,

but taking a third-rate operetta, which people don't take seriously anyway,

which has horrible traditions and is usually sung very badly, taking that

and being disciplined about it and making something out of it is incredibly

hard, and you learn a lot doing it. He did that and then moved to

a somewhat larger theater - Aachen - and I think he spent four or five

years there, and that's still smaller than Krefeld - Mönchengladbach.

Only then did he go to Berlin. He spent that time turning those theaters

into better ones than when he first got there. This is what I wanted

to do. So when I got an offer to move to Germany as a 28-year-old

to be the youngest Chief Conductor of any German opera house, I jumped

at the opportunity. I spent six long, hard years doing all of that

there. After two or three years, I could have done things that were

much more visible and people asked me why I stayed there, and I said that

I hadn't completed my education. By the end of six years, I really

had done everything I could at that level, and I felt ready to move to

Berlin.

= = = = = = =

- - - - -

= = = = = = =

©Bruce Duffie

Published in The Opera Journal June, 2002

Be sure to visit Bruce Duffie's Personal

Website [ http://www.bruceduffie.com ]

and send him E-Mail[

duffie@voyager.net ]

He

studied conducting privately with Ilya A. Musin, (the renowned Professor

of Conducting from the St. Petersburg Conservatory), before emigrating

to the United States in 1976. There he was awarded conducting fellowships

at Tanglewood with Leonard Bernstein, Seiji Ozawa and Erich Leinsdorf,

and at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute, where he was invited back

as assistant to Michael Tilson Thomas.

He

studied conducting privately with Ilya A. Musin, (the renowned Professor

of Conducting from the St. Petersburg Conservatory), before emigrating

to the United States in 1976. There he was awarded conducting fellowships

at Tanglewood with Leonard Bernstein, Seiji Ozawa and Erich Leinsdorf,

and at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute, where he was invited back

as assistant to Michael Tilson Thomas.

Obviously,

I always wanted to grow and be better, because you always feel limited

by your own knowledge. I was never very keen to make a quick splash.

It would have been relatively easy because if you are young and if you

are talented, it's really not all that difficult if you're in the right

place at the right time. You can jump in for somebody who is ill,

or go and conduct one or two repertoire performances in a European opera

house, put them on your resume and progress that way. I didn't feel

that was right for me. I felt that I was a slow learner, even though

to most people I was an incredibly fast learner. You could put a

score in front of me and I could play it for you on the piano. I

learned that when I was a teenager. I could sight-read anything.

I used to accompany singers. When I came to New York at age sixteen,

I used to play in all the voice studios. I made my living that way

and put myself through college.

Obviously,

I always wanted to grow and be better, because you always feel limited

by your own knowledge. I was never very keen to make a quick splash.

It would have been relatively easy because if you are young and if you

are talented, it's really not all that difficult if you're in the right

place at the right time. You can jump in for somebody who is ill,

or go and conduct one or two repertoire performances in a European opera

house, put them on your resume and progress that way. I didn't feel

that was right for me. I felt that I was a slow learner, even though

to most people I was an incredibly fast learner. You could put a

score in front of me and I could play it for you on the piano. I

learned that when I was a teenager. I could sight-read anything.

I used to accompany singers. When I came to New York at age sixteen,

I used to play in all the voice studios. I made my living that way

and put myself through college.