|

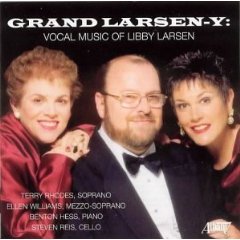

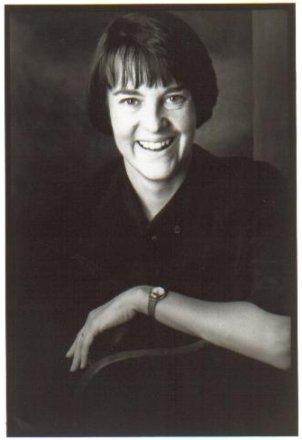

Libby Larsen (b. 24 December 1950,

Wilmington, Delaware) is one of America’s most performed living composers.

She has created a catalogue of over 400 works spanning virtually every genre

from intimate vocal and chamber music to massive orchestral works and over

twelve operas. Grammy Award winning and widely recorded, including over fifty

CD’s of her work, she is constantly sought after for commissions and premieres

by major artists, ensembles, and orchestras around the world, and has established

a permanent place for her works in the concert repertory.

As a vigorous, articulate advocate for the music and musicians of our time, in 1973 Larsen co-founded the Minnesota Composers Forum, now the American Composer’s Forum, which has become an invaluable aid for composers in a transitional time for American arts. A former holder of the Papamarkou Chair at John W. Kluge Center of the Library of Congress, Larsen has also held residencies with the Minnesota Orchestra, the Charlotte Symphony and the Colorado Symphony. |

BD: Do you view your music, then, as exploratory or reflective?

BD: Do you view your music, then, as exploratory or reflective? BD: I assume that you are overloaded with commissions, and

requests for pieces. How do you decide which ones you will accept,

which ones you'll postpone and which ones you'll say, "Never"?

BD: I assume that you are overloaded with commissions, and

requests for pieces. How do you decide which ones you will accept,

which ones you'll postpone and which ones you'll say, "Never"? LL: To me, the human voice is the ultimate instrument.

It's the most reflective, the most personal, the most infinite in its possibilities

and the most difficult to write for if you are not willing to accept the fact

that the human voice is a kinetic instrument. The composer needs to

approach it psychologically. For me, the joys of writing for it are

that it is infinitely expressive, especially now that we have microphones;

we can express the most intimate sigh along with the most noble high C, and,

we can mix them into the same piece if we want. So we are able to get

at the human voice in a way that we weren't before we had studios and technology.

LL: To me, the human voice is the ultimate instrument.

It's the most reflective, the most personal, the most infinite in its possibilities

and the most difficult to write for if you are not willing to accept the fact

that the human voice is a kinetic instrument. The composer needs to

approach it psychologically. For me, the joys of writing for it are

that it is infinitely expressive, especially now that we have microphones;

we can express the most intimate sigh along with the most noble high C, and,

we can mix them into the same piece if we want. So we are able to get

at the human voice in a way that we weren't before we had studios and technology. LL: I don't allow very much, actually; funny you should ask

that. I try to put as much on the page as I possibly can. I even

stopped writing articulation directions in any language other than English.

I now try to put everything on the score in American English.

LL: I don't allow very much, actually; funny you should ask

that. I try to put as much on the page as I possibly can. I even

stopped writing articulation directions in any language other than English.

I now try to put everything on the score in American English.This interview was recorded in Chicago on April 11, 1988. Portions

were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1990, 1995, 1997 and 2000; and

on WNUR in 2007. A copy of the audio tape was given to the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern

University. The transcript was made and posted on this website in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.