BD: Do

composers today not understand the voice?

BD: Do

composers today not understand the voice? EL: No. I make

here a very clear distinction

— and I have written about it

— that recordings should never be used by the

professional performer as a study aid or as a means to learn the

music. As such, recordings are absolute poison for the

professional who misuses them. For the public, I think they are a

great and lasting benefit.

EL: No. I make

here a very clear distinction

— and I have written about it

— that recordings should never be used by the

professional performer as a study aid or as a means to learn the

music. As such, recordings are absolute poison for the

professional who misuses them. For the public, I think they are a

great and lasting benefit. EL: It gives

you freedom, and I would broaden this by

saying it is not only for a musician, it is for any professional, even

in business. An orchestra organization is as any other

corporation, so I want you to take this as a broad statement, going

through the entire spectrum of our society and civilization. If

you are a member, no matter how high up, of an organization, between

you and your aims and objectives you have always to consider a number

of issues which are not entirely part of your aims. This is true

if that be public relations, if that be labor relations, if that be

personal relations, if that be overexposure or underexposure. In

show business, there’s all these things. If it is a board of

directors or whatever it is, you are not your own completely free

agent. Let us say you are a professional cook. If you have

your own little diner and you are alone in the kitchen, you decide what

menu to produce, how to produce it, what the portions will be, what the

price will be. You are in direct contact with your customers and

you gauge yourself as to what you want to produce and how it is

liked. If you are chef in a large, distinguished restaurant, you

may get a better salary and you have no risk, but you never are in

direct touch with your objective — how

your food sits with your audiences — because

you have so many in-between decisions which either you don’t make, or

to which you have to adjust, or which you pretend you make when it is

really made by others. This is the same if you are a cooking chef

or an orchestra chef or a bank president or head of a retail

chain. It makes absolutely no difference. You are an

independent, free person only if you are not affiliated with an

organization. This is my great wisdom-finding going up to age

seventy-five.

EL: It gives

you freedom, and I would broaden this by

saying it is not only for a musician, it is for any professional, even

in business. An orchestra organization is as any other

corporation, so I want you to take this as a broad statement, going

through the entire spectrum of our society and civilization. If

you are a member, no matter how high up, of an organization, between

you and your aims and objectives you have always to consider a number

of issues which are not entirely part of your aims. This is true

if that be public relations, if that be labor relations, if that be

personal relations, if that be overexposure or underexposure. In

show business, there’s all these things. If it is a board of

directors or whatever it is, you are not your own completely free

agent. Let us say you are a professional cook. If you have

your own little diner and you are alone in the kitchen, you decide what

menu to produce, how to produce it, what the portions will be, what the

price will be. You are in direct contact with your customers and

you gauge yourself as to what you want to produce and how it is

liked. If you are chef in a large, distinguished restaurant, you

may get a better salary and you have no risk, but you never are in

direct touch with your objective — how

your food sits with your audiences — because

you have so many in-between decisions which either you don’t make, or

to which you have to adjust, or which you pretend you make when it is

really made by others. This is the same if you are a cooking chef

or an orchestra chef or a bank president or head of a retail

chain. It makes absolutely no difference. You are an

independent, free person only if you are not affiliated with an

organization. This is my great wisdom-finding going up to age

seventy-five. EL: That is a

very, very interesting and good

question. I want to be very cautious about this because sometimes

composers need not be necessarily their best interpreters. There

are things on record in the rewritings of Stravinsky which prove that

he did things differently the moment he started conducting; these did

not necessarily improve things in the ways of tempi and in

transitions. I could go specifically into it, but it would make

no sense because you actually need examples at the blackboard or a

projecting machine to show the music. But let me assure you, I

have done this in my seminars for conductors to show how the later

versions of Stravinsky were affected by his own conducting.

EL: That is a

very, very interesting and good

question. I want to be very cautious about this because sometimes

composers need not be necessarily their best interpreters. There

are things on record in the rewritings of Stravinsky which prove that

he did things differently the moment he started conducting; these did

not necessarily improve things in the ways of tempi and in

transitions. I could go specifically into it, but it would make

no sense because you actually need examples at the blackboard or a

projecting machine to show the music. But let me assure you, I

have done this in my seminars for conductors to show how the later

versions of Stravinsky were affected by his own conducting. EL: I don’t

know because thirty, forty, fifty years

ago what I heard was then all new to me. I did not have the

critical faculty — or the

uncritical faculty [laughs] — which

ever way you want. I had different ears and a different

receptivity. I could not answer this question honestly; I would

only have to speculate, and my speculation is that they were certainly

not worse. I cannot say that they were better because I don’t

think so. In a printed interview in Piano

Quarterly, I commented on an article in which the critic Harold

Schoenberg was very hard on the young pianists. He found little

merit in them when compared to the grand old masters such as Friedman,

Rosenthal, Pachmann, Rubenstein, etcetera, etcetera. I said that

I thought that was a little unfair. I don’t think that the young

ones are all missing in romanticism, or whatever Harold complained

about. I think the outward situation of the artist today has

changed, and I will say quite frankly what performers today take on in

scheduling themselves must have an adverse effect on their involvement

when they actually go up on stage. You cannot carry on the way

some of these people carry on — with

airplane rides and last-minute arrivals, with quick rehearsals and

meetings in between — and

then go on and do some of the challenging works of the music

literature. It cannot be as involved and as intense as when one

[pounds hand on table] sat and took one’s time and had preparation of

various kinds. Also, in one’s own inner life, I don’t think that

it is possible to carry on as some people carry on today.

EL: I don’t

know because thirty, forty, fifty years

ago what I heard was then all new to me. I did not have the

critical faculty — or the

uncritical faculty [laughs] — which

ever way you want. I had different ears and a different

receptivity. I could not answer this question honestly; I would

only have to speculate, and my speculation is that they were certainly

not worse. I cannot say that they were better because I don’t

think so. In a printed interview in Piano

Quarterly, I commented on an article in which the critic Harold

Schoenberg was very hard on the young pianists. He found little

merit in them when compared to the grand old masters such as Friedman,

Rosenthal, Pachmann, Rubenstein, etcetera, etcetera. I said that

I thought that was a little unfair. I don’t think that the young

ones are all missing in romanticism, or whatever Harold complained

about. I think the outward situation of the artist today has

changed, and I will say quite frankly what performers today take on in

scheduling themselves must have an adverse effect on their involvement

when they actually go up on stage. You cannot carry on the way

some of these people carry on — with

airplane rides and last-minute arrivals, with quick rehearsals and

meetings in between — and

then go on and do some of the challenging works of the music

literature. It cannot be as involved and as intense as when one

[pounds hand on table] sat and took one’s time and had preparation of

various kinds. Also, in one’s own inner life, I don’t think that

it is possible to carry on as some people carry on today. EL: Oh,

yes! You must never take certain things

for granted. From a different field, if you eat caviar three

times a day, it will take a few days and then first of all you’ll ruin

your stomach, and second of all you’ll be sick of caviar

— instead of looking forward to this great

privilege of this exquisite fish egg.

EL: Oh,

yes! You must never take certain things

for granted. From a different field, if you eat caviar three

times a day, it will take a few days and then first of all you’ll ruin

your stomach, and second of all you’ll be sick of caviar

— instead of looking forward to this great

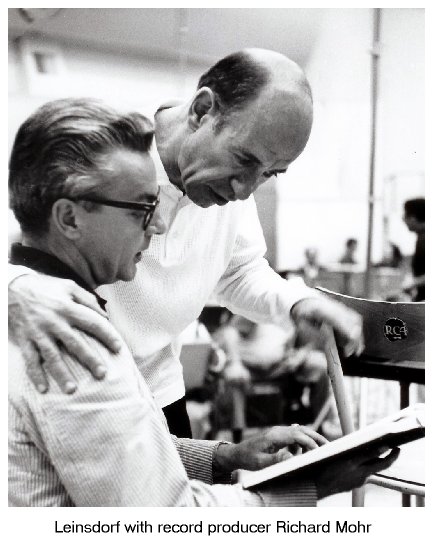

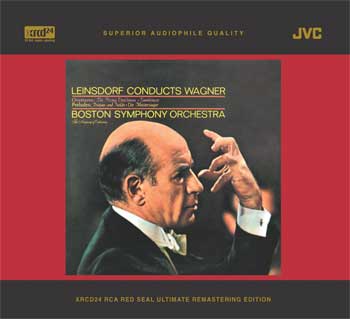

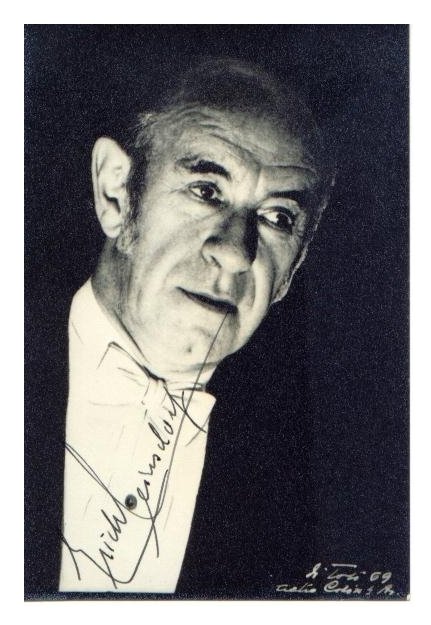

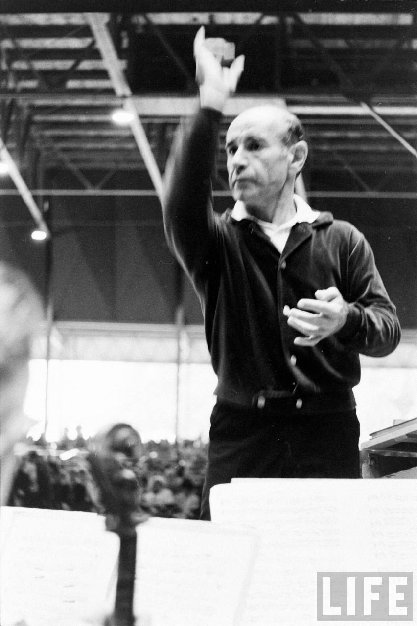

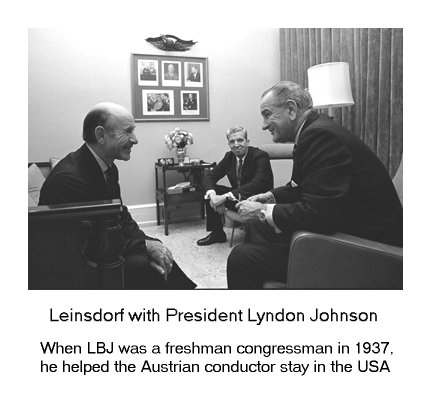

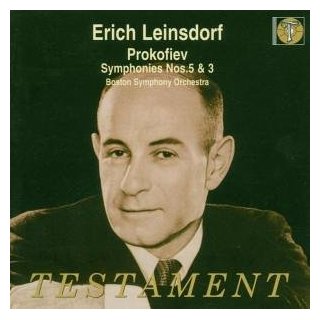

privilege of this exquisite fish egg.Erich Leinsdorf, 81, a Conductor of

Intelligence and Utility, Is Dead

By BERNARD HOLLANDPublished: Sunday, September 12, 1993, in The New York Times Erich Leinsdorf, a conductor whose abrasive intelligence and deep musical learning served as a conscience for two generations of conductors, died yesterday at a hospital in Zurich. He was 81 years old and lived in Zurich and Sarasota, Fla., and until recently also had a home in Manhattan. The cause was cancer, his family said. Mr. Leinsdorf's utilitarian stage manner and his disdain of dramatic effects for their own sake stood out as a not-so-silent rebuke to his colleagues in this most glamorous of all musical jobs. In addition, Mr. Leinsdorf -- in rehearsal, in the press and in his valuable book on conducting, "The Composer's Advocate" -- never tired of pointing out gaps in culture among musicians, faulty editing among music publishers and errors in judgment or acts of ignorance among his fellow conductors. He rarely named his victims, but his messages and their targets were often clear. Moreover, he usually had the solid grasp of facts to support his contentions. His long career continued until early this year, when his health deteriorated. After conducting the New York Philharmonic in January, he was forced to cancel performances the next month. Help From Toscanini Mr. Leinsdorf moved to this country from Vienna in 1937. Helped by the recommendation of Arturo Toscanini, whom he had been assisting at the Salzburg Festival, Mr. Leinsdorf made his conducting debut at the Metropolitan Opera a year later with "Die Walkure." He was 25 years old at the time. A year later he was made overseer of the Met's German repertory, and his contentious style -- in particular an insistence on textual accuracy and more rehearsal -- won him no friends among singers like Lauritz Melchior and Kirsten Flagstad. Backed by management, he remained at the Met until 1943. At the New York City Opera, where he became music director in 1956, Mr. Leinsdorf's demanding policies in matters of repertory and preparation made him further enemies, and he left a year later. His searches for permanent employment turned mostly to orchestras. After the briefest of tenures at the Cleveland Orchestra during World War II, Mr. Leinsdorf took over the Rochester Philharmonic and stayed for nine years. During that period, he and the orchestra made a series of admired low-budget recordings that brought Rochester to the music world's attention. Mr. Leinsdorf's last and most prestigious music directorship was at the Boston Symphony, where he replaced Charles Munch in 1962. No contrast in style could have been sharper: Munch had viewed conducting mystically, as a kind of priesthood; Mr. Leinsdorf's policy was to make performances work in the clearest and most rational way. Cool Objectivity Observers both in and out of the orchestra could not deny the benefits of Mr. Leinsdorf's discipline, but there were some who were hostile to what they perceived as an objectivity that could hardly be called heartwarming. Perhaps his principal achievements with the Boston Symphony were not in Boston but at the Tanglewood Music Festival, where he presided over the orchestra's summer season in the Berkshires. There Mr. Leinsdorf introduced 32 works, including Benjamin Britten's "War Requiem," and began a Prokofiev cycle. He also worked closely with Tanglewood's conducting students. The administrative and social burdens of the music director's job became increasingly onerous to him, however, and not enjoying total enthusiasm from the press, he stepped down after the 1968-69 season. "Only six years earlier," he remarked at the time, "I had been overjoyed at being asked to a position considered one of the most prestigious in my profession, and now I could only hope to get out with my health intact." Subsequently, Mr. Leinsdorf found happiness as a guest conductor, touring the world's major orchestras, working with them for several weeks at a time and avoiding the burdens of a permanent position. Although his performances were rarely dramatic or even rousing, he brought to music a kind of rectitude that at its best provided an antidote for orchestra musicians and listeners used to flamboyant and often empty conductorial salesmanship. One American orchestra manager a few years ago responded to musicians' grumblings over Mr. Leinsdorf's rehearsal manner by saying that he was "good for my orchestra." And so he probably was. Played for Webern Erich Leinsdorf was born in Vienna on Feb. 4, 1912, to Ludwig Julius and Charlotte Loebl Leinsdorf. His father, an amateur pianist, died when Mr. Leinsdorf was 3 years old. Mr. Leinsdorf was already a good pianist by age 7. As a teen-ager he studied the cello, musical theory and composition at the University of Vienna and at the city's Music Academy. He was a rehearsal pianist for Anton Webern when that most ascetic of composers was conductor of a chorus known as the Singverein der Sozialdemokratischen Kunstelle; there he made his professional piano debut in a performance of "Les Noces" by Stravinsky. Aside from the early Rochester recordings, Mr. Leinsdorf recorded extensively for the RCA label, including full operas, all the Mozart symphonies, other items from the standard repertory, and modern works by Elliott Carter, Alberto Ginastera and others. Mr. Leinsdorf's first marriage, to Anne Frohnknecht, ended in divorce. He is survived by his wife of 25 years, the former Vera Graf, and five children from his first marriage: David I. of Crested Butte, Col., Gregor J. of Manhattan, Joshua F. of Atlantic Highlands, N.J., Deborah Hester Reik of Hartford, Jennifer G. Belok of Belmont, Mass., and 10 grandchildren. A version of this obituary; biography appeared in print on Sunday, September 12, 1993, on section 1 page 58 of the New York edition. |

These interviews were recorded in

Chicago on March 19, 1983, and December 15, 1986. Portions were

used (along with

recordings) on WNIB in 1987, 1989, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1997

and 1999. The first interview was transcribed and published in Wagner News in June of 1984.

It was re-edited along with the second interview which was

transcribed and posted on this website in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award-winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.