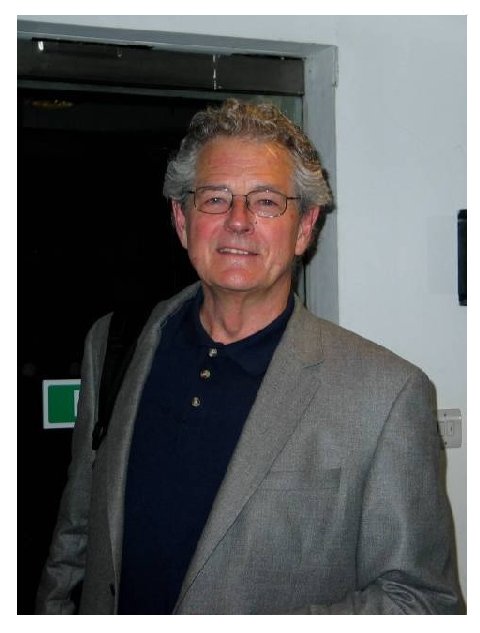

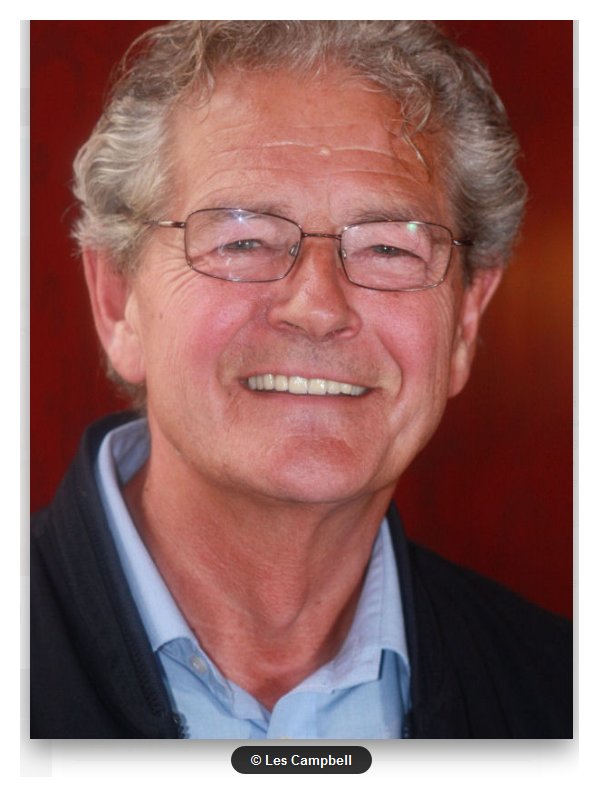

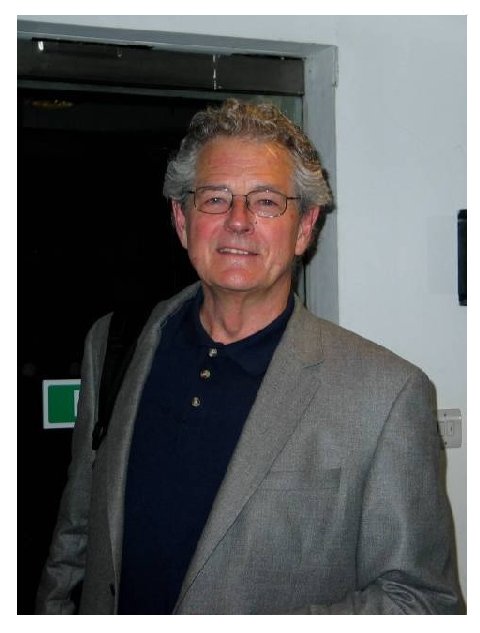

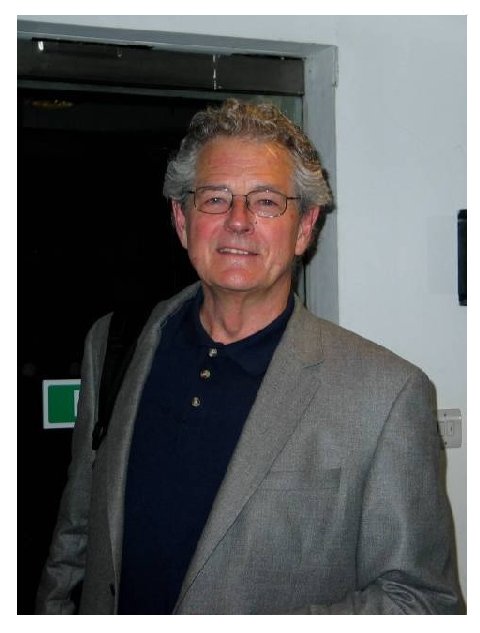

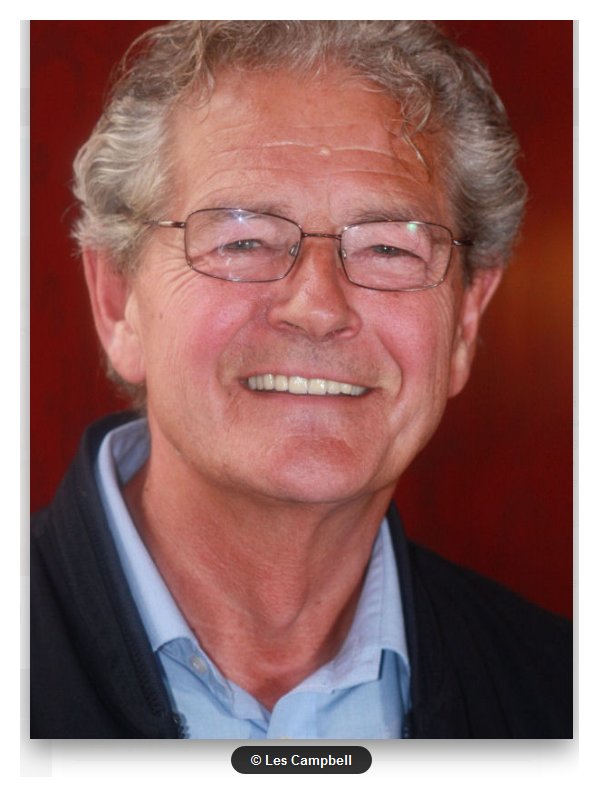

Bass Robert Lloyd

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

One of Britain greatest singers,

Robert Lloyd became the Principal Bass at the Royal Opera House, Covent

Garden in 1972. He has since sung an enormous range of repertoire with

the company and is now their senior artist.

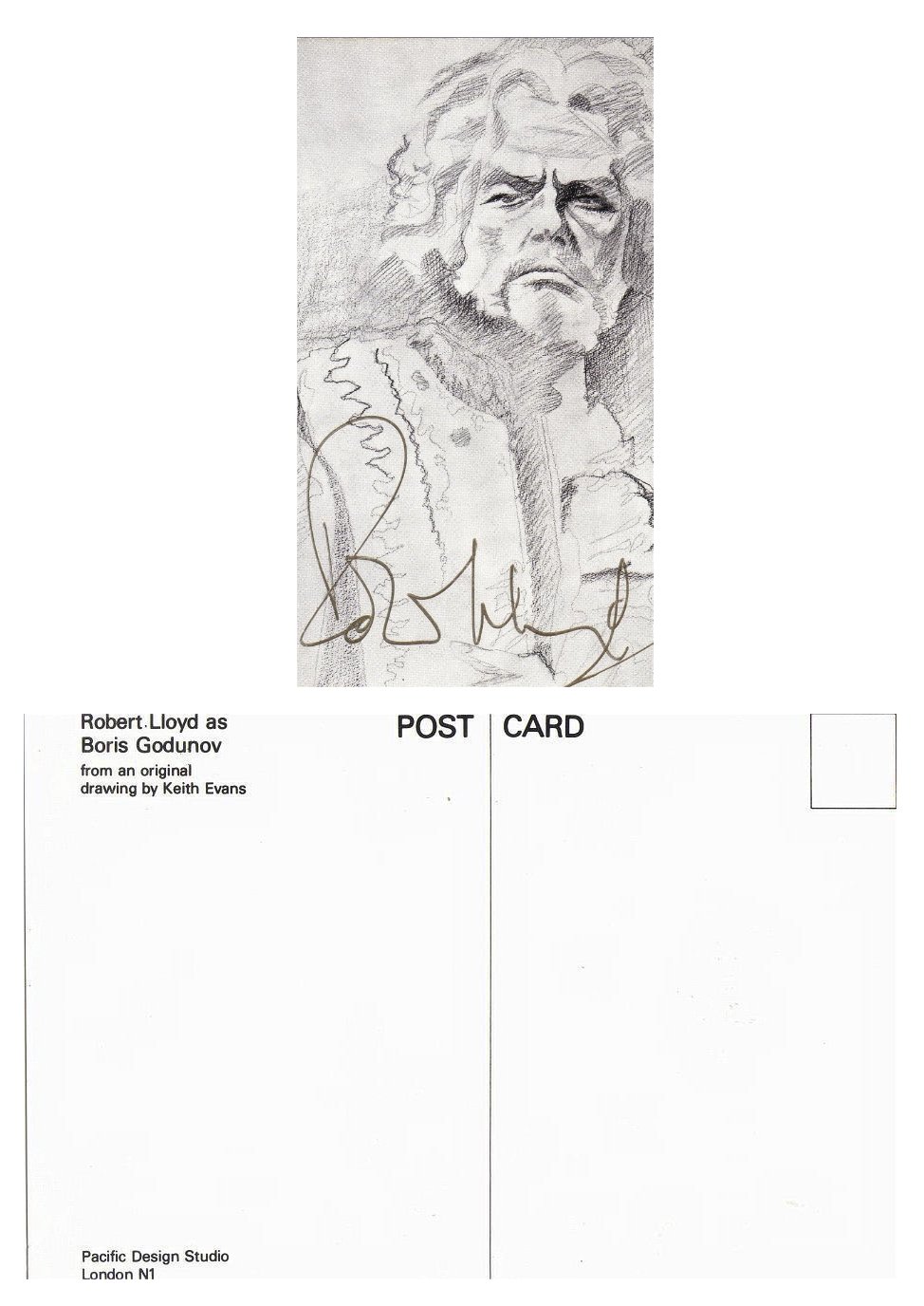

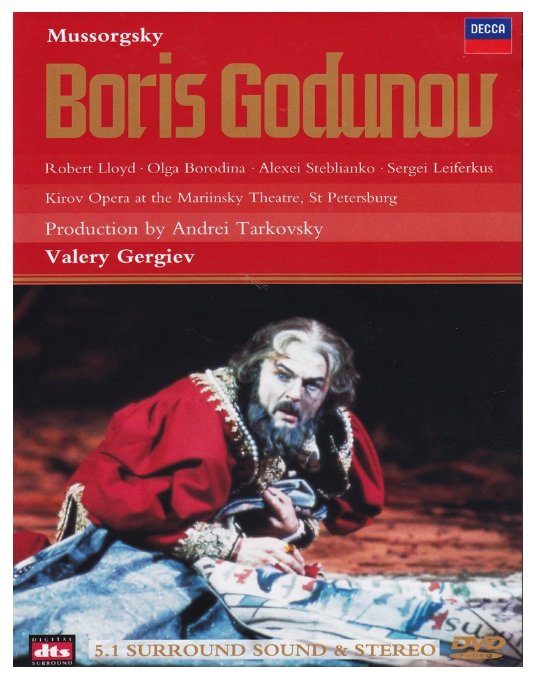

Robert Lloyd was the first British bass to sing the title role in Boris Godunov at Covent Garden and

made history when he sang the role with the Kirov Opera in St

Petersburg. He sings the great roles of his repertoire in Paris,

Salzburg and San Francisco and for many years has had a particularly

close association with the Metropolitan Opera, New York.

He has a vast discography of over seventy audio and video recordings.

In the 1991 New Year Honours List, Robert Lloyd was created a Commander

of the British Empire (CBE). Robert Lloyd collaborated with the artist

Pip Woolf and pianist Julius Drake in 1999 to produce a recital

/exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art in Wales of Schubert's

'Winterreise'. This

subsequently led to the production of a CD/book complete with

paintings, drawings and his personal score of the music.

|

Robert Lloyd made his debut in Chicago as Sarastro in The Magic Flute in January of

1991. He would later return for Don Diègue in Le Cid and also Fiesco in Simon Boccanegra.

Between performances in that first season, I had the pleasure of

meeting with the distinguished bass at his apartment. While

setting up the tape recorder, I explained the various purposes of the

interview. Besides including portions during broadcasts of

complete operas on Sundays, I celebrated “round

birthdays” of my guests with special programs. So I

asked him for his birthdate (March 2, 1940, which he gave me

accurately) and seemed amused by the idea . . . . . . .

Robert Lloyd:

It’s a very round number in my life — 1940

— beginning of the War in England and that’s when I was

born.

Bruce Duffie:

So now you are fifty, or almost at fifty-one. Are you where you

expected to be in your career?

RL: I’m

pretty well where I would have hoped to be, really. I’ve done

most of the roles that I want to do. There are one or two which

I’d still like to do, and one or two that I might venture upon,

slightly foolhardily, maybe. And I’m singing in all the greatest

opera houses in the world, so I can’t really complain. It worked

out quite well. For a bass, life is a good deal more orderly and

straightforward than it is for young women, or for tenors.

BD:

Really? Why?

RL: Because

we get more relevant the older we get. We’re always playing these

old men, gray bearded creatures I might say. We’re fathers and

priests, and symbols of authority.

BD: Fathers,

priests, and devils seem to always be the bass.

RL: There’s

only one devil, but I suppose there are several manifestations of

Mephistophele, so that’s true, yes. I always forget about him,

but I never think of the Gounod Mephistopheles as the devil. He’s

rather a charming lad, I think. [Laughs]

BD: Do you sing him?

BD: Do you sing him?

RL: Yes, I’ve

done it.

BD: Do you

also sing the Boito?

RL: No, I

haven’t done that one. I’ve done the Berlioz, but that’s really a

concert piece. I have actually the small part of Brander on stage

in a staging in London, but for the Mephistopheles I’ve only done that

in concert.

BD: You like

playing the Devil?

RL: Oh yes,

yes. As I say, he’s rather a charming chappy.

BD: Are you

making him, perhaps, too charming?

RL:

Hmm. I don’t think Gounod takes him terribly seriously.

[Both laugh] I’m not too sure Gounod takes anything terribly

seriously. It’s very difficult to make him genuinely

sinister. Probably the way to play that Mephistopheles is in the

old-style tradition, where they put spangles on their eyelids to make

them flash in the lights, and just play it up, really camp it up into

something rather sharp and brilliant. To play for the

heavyweight, lugubrious, sinister-ness doesn’t work.

BD: So it’s

right, then, that he actually loses in the end?

RL: Oh, sure!

Absolutely, yes.

BD: Does it

become a morality play, then?

RL: I suppose

it was designed to be something of a morality play. That sort of

thing wouldn’t have, I suppose, survived the censorship unless it had

an element of morality about it. I don’t think he could let the

Mephistopheles win, not on the Victorian stage.

BD: Should he

win?

RL: He seems

to, doesn’t he, quite a lot?

BD: He winds

up with Faust, but not Marguerite.

RL: I didn’t

mean in the opera, I meant in life in general. He seems to have

quite a degree of success.

BD:

Hmmmm! Should opera, then, be made relevant to preach to today’s

society and maybe get them back on the straight and narrow?

RL: It would

be nice if we could find a medium where we could communicate something

worth saying on the operatic stage. It’s a very powerful

medium. Unfortunately, the composers seem to have lost their

grasp of the audiences. It seems to me that composers

increasingly in this century have composed for one another rather than

for their audiences. I’ve been very impressed by the initiative

of the Chicago Opera in this with their “Towards the Twenty-First

Century.” I think that’s a marvelous idea, really

wonderful. People tend to think of the 20th Century as a century

of difficult compositions with strange and inaccessible

compositions. But in actual fact, some of the greatest pieces

that we regularly perform are, in fact, 20th Century. I mean, all

the Puccini pieces...

BD: But

that’s very early on.

RL: That’s

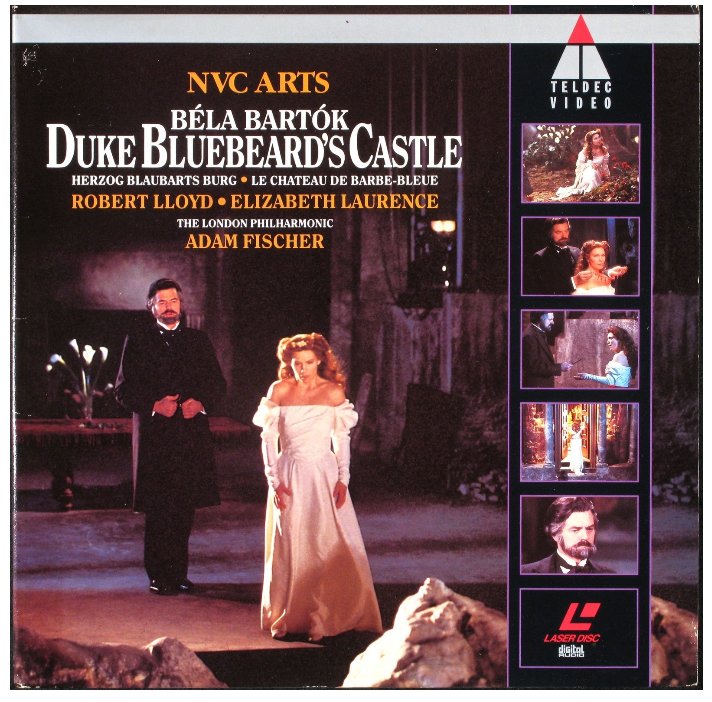

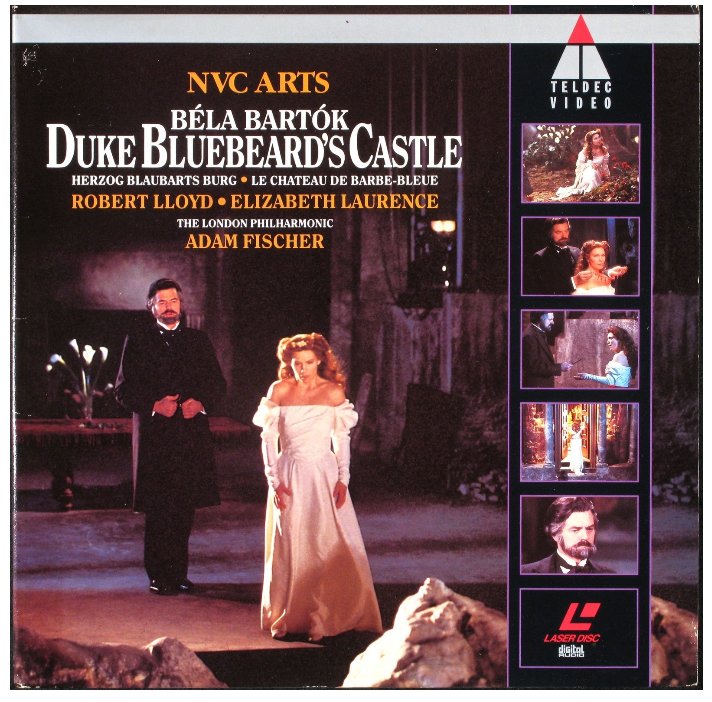

right, and Bluebeard’s Castle,

which is perhaps one of the most intelligent operas I’ve ever

performed. Peter Grimes

is a sensational masterpiece. There’s a lot of stuff there in the

20th Century, but somewhere in the middle we lost our way. We

didn’t communicate with the audiences properly.

BD: Do you

have some advice for composers who want to write for the human voice?

RL: It’s a

bit sort of cliché. I’m not really able to give advice; I

can only speak from my experience, and that is that I do believe that

the human voice is an exceedingly exciting instrument. It’s got

so much opportunity for range, color, excitement and nuance, that it’s

sad when a modern composer treats it as a percussion instrument or an

instrument of the orchestra, not consulting the essential richness of

color in the human voice. It only has that color when it expands

fully, when it’s being used fully and sonorously to its maximum.

With a great deal of modern music, you just can’t do it. You

can’t use the voice fully. It’s being used as a staccato

instrument, which I think denies its very nature.

BD: So really

you want the composer to exploit the powers of the voice more than they

do?

RL: I do,

very much so, yes. And of course, to some extent that means

writing tunes. [Laughs] There’s nothing quite to compare

with a tune. It’s a bit like talking about novels or any art form

really. The form it takes is so important. The essence of a

good novel is the story line. The characterization and the

dialogue and all those other things are extremely important, but the

story line is what really holds the audience. That’s what we need

in opera. We need to look at opera for what it really is.

It’s a fantastic medium for conveying high-powered emotion through the

human voice. You’ve got to use the human voice to the maximum to

realize its real nature. That’s my feeling.

BD: Are you

optimistic about the future of opera?

RL: I get

little, maybe one or two glimmers of hope. It’s been a bit of a

dark period all the time I’ve been singing. I’ve very much

regretted the fact that I haven’t been able to find modern composers

that I feel I can relate to.

BD: Because

you’d like to find someone to champion?

RL: That’s

right, absolutely. I would like to feel like a creative

artist. I would like to take part in something new. I would

like to say something. I would like to communicate important,

urgent messages to my public, but it’s really not possible to do

that. It’s such a shame that the great issues of our day are not

explored in opera. Apartheid, nuclear holocaust, all the various

holocausts of the last fifty years aren’t explored in opera.

These are tremendous subjects with a lot of the things that voices are

good at expressing — like pain, joy and

conflict. So yes, I’d love to find some vehicle for that.

BD: Are there

not enough vehicles in what’s already been written of past problems,

which may or may not have been solved already?

RL: What

they’re trying to do is reinterpret past operas to make them creatively

relevant to the present by changing the period, by changing the

costumes, by updating it as they call it, and that seems pretty

unsatisfactory to me. Sometimes it works. Just occasionally

it works sufficiently to make the whole process really interesting and

not something you can dismiss out of hand. But it works very

infrequently, and it seems to deny very much the nature of opera.

BD: But

leaving it in the correct period with costumes and staging that would

be completely relevant and completely straightforward for the piece, do

you enjoy re-creating these pieces that have been around for a hundred

or two hundred years?

RL: Oh,

sure. Oh, absolutely! They are wonderful things, and of

course they don’t have to be completely in period. I can quite

see that to do, for instance, Rigoletto

in medieval costumes, with the clown with his jangly bells and

things. But once you’ve seen it like that a few times, it does

pall a little. There’s a case for doing it like that from time to

time, of course, because it has a kind of historical quality,

especially in an environment where you’re not actually in touch very

much with medieval history, like the United States. It’s really

quite important that you see things in period costume. In Europe,

though, it palls us after a while, but there is no need for it to be

any specific period. It just doesn’t have to be in Nazi costumes

as far as I can see it.

BD: In other

words, if you’re going to do a Nazi opera, write a Nazi opera?

RL:

Precisely, yes. I saw a performance of Rossini’s Mosè at the London Coliseum

where people were going around with Tommy guns and wearing gray striped

suits. It didn’t line up with Rossini’s formal musical

construction with lots of florid writing. It just wasn’t

consonant with the music in any way.

BD: So

everything has to agree — the colors, the staging, the music, the

drama. Everything has to be a unit for you?

RL: Yes,

indeed. I think any director of opera has to listen very, very

intently to the music and let his interpretation of the piece grow out

of the music. The problem that we run into a great deal is

because there are a lot of opera directors nowadays who come from the

straight theater, they tend to look only at the text, or at least

predominantly at the text. They construct their production

edifice from the text. Now you know as well as I know that a lot

of texts in operas are pretty absurd and very limited. It is in

the nature of music that it releases the undertones and the overtones,

the nuances and the colors and the emotions that go inside a very

simple text. Music makes any text much bigger than it really

is. I always think of the text as a kind of seed, and out of that

the whole tree of the musical form grows. But it’s only the

starting point; it’s not something that you can put too much weight

upon as it is, and that’s the problem with most modern directors.

They read only the text.

BD: Where is

the balance, then, between the music and the drama?

RL: There’s

no way I can generalize about that. You have to take a specific

example and start listening a lot to the music until it becomes part of

your muscle structure. Another problem that modern directors have

is that a lot of them don’t quite understand how much the music becomes

part of the psyche and the muscle structure and the reflex system of

the singers. Sometimes we turn up to rehearsals and we are being

encouraged to do something in a particular way which runs counter to

everything the music says to us. That puts us under tremendous

stress! I mean real, real stress. That’s real ulcer country

when that happens. [Laughs] I’ve come to understand that’s

partly because the producers don’t have that same actual physical

reflex, a physical reaction to the music, because they don’t know the

music so well. The singer lives with the music for a year or

more, and if you’ve done a role a few times then you’ve lived with it

for many years. Even if it’s new, you would have lived with it

for several months.

BD: And no

matter what you’re doing, you’re still living with the same music!

RL: That’s

right, yes. It has its own rhythm and its own shape, and it

suggests movements to you. You’re always reacting to the music as

it presents itself. The producer isn’t doing this; he’s standing

outside the scene looking in, and that’s a source of an awful lot of

difficulties. I don’t think all this has quite hit the States

yet, but with Peter Sellars it’s coming. I think the opera world

in the States is going to have a difficult time for the next few years.

BD: Or are we

going to skip it? Are we going to see what it’s doing to Europe,

and decide we don’t want this coming over?

RL: It may be

that you pick up the good bits. That’s possible, yes. That

would be a very shrewd thing to do. [Both laugh]

*

* *

* *

BD: When

you’re on stage, are you portraying a character or do you actually

become that character?

RL: Ah well, people

vary on that. My family tend to think I become the character, but

I like to think I portray it. I don’t know whether everybody has

to work this way in order to get a good result, but the way I work is

that I have to find the character. I have to find the personality

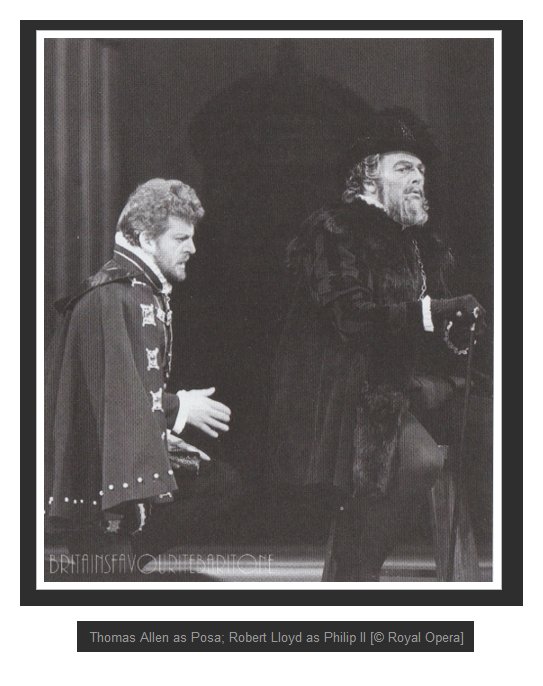

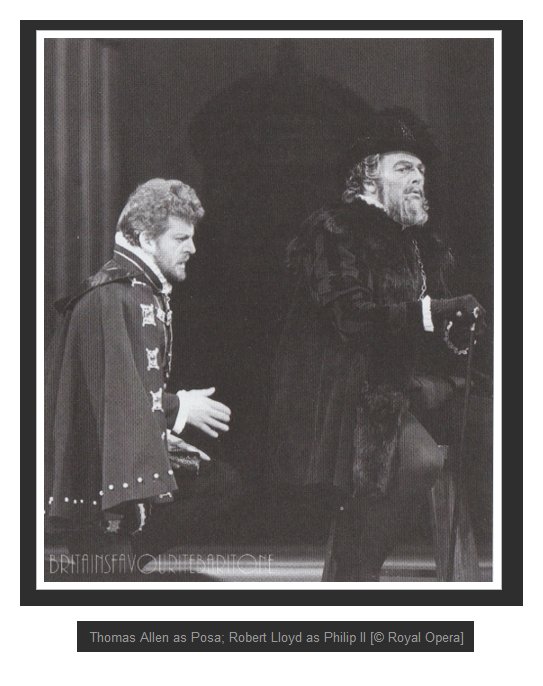

in myself at some stage during rehearsals. King Philip I always

think of as a tyrant who is a tyrant because he’s fundamentally a

wimp. He lashes out at everything in a rather uncontrolled

fashion because he deeply distrusts his own real inner core. So I

look for those characteristics in myself and write it out from

there. By the time I arrive on the stage for the first night,

I’ve discovered this character. I’ve photocopied him, as it were;

I can reproduce him at will. But I don’t think at the time, on

the stage on the first night, I’ve been King Philip. I’m doing a

duplicate version of something I discovered in rehearsal.

RL: Ah well, people

vary on that. My family tend to think I become the character, but

I like to think I portray it. I don’t know whether everybody has

to work this way in order to get a good result, but the way I work is

that I have to find the character. I have to find the personality

in myself at some stage during rehearsals. King Philip I always

think of as a tyrant who is a tyrant because he’s fundamentally a

wimp. He lashes out at everything in a rather uncontrolled

fashion because he deeply distrusts his own real inner core. So I

look for those characteristics in myself and write it out from

there. By the time I arrive on the stage for the first night,

I’ve discovered this character. I’ve photocopied him, as it were;

I can reproduce him at will. But I don’t think at the time, on

the stage on the first night, I’ve been King Philip. I’m doing a

duplicate version of something I discovered in rehearsal.

BD: Now of

course Philip is actually an historical figure. Does your study

process change when you’ve got someone you can really see and know in

history, as opposed to a fictional character that’s made up out of some

librettist’s mind?

RL: When I

first started these lead characters, I had to make some

decisions. I started life as a historian myself, so I thought the

serious and earnest and intelligent thing to do was to look at these

characters historically to discover the operatic character. But

then I discovered that the operatic characters are so far from any sort

of historical context. [Both laugh] Don Carlos, for

instance, if I remember correctly, would be a ten year-old half wit

rather than a forty year-old tenor if historical accuracy was being

consulted. So I tend to look at the period for background color,

but not the historical identities of the characters because they’re

misleading. If you go along and try to do King Philip as you

discover him, then it doesn’t work for you. You have to actually

look at the music and see what it says. Listen to the music;

start from there.

BD: So, you

have to do King Philip as Verdi and the librettist discovered him?

RL: That’s

right, yes. They’re figments of the imagination, really.

They’re not genuine historical characters at all. They’re so

circumscribed by the mood Verdi happened to feel in that day. He

wrote tunes according to his feeling. He didn’t write tunes

according to his historical research on the character.

BD: Coming

back briefly to what we were talking about earlier, if he were to start

to do an opera on Apartheid and you had to write a character of Mandela

or somebody else involved in that whole movement, the people today

would know enough about him that they would know when the character

deviates from real life. So you wouldn’t have that kind of

expansion and expandable liberties.

RL: That’s

true, yes, but you would be writing now about Mandela from a point of

view that knows Mandela reasonably from the media. When Verdi was

writing, he didn’t know Philip II. He was at the same sort of

distance from Philip II that we are, and that makes the

difference. In any case, I’m not sure that music is so good at

doing pen portraits of people. It creates emotional moods.

It creates the environment in which people happen. A very good

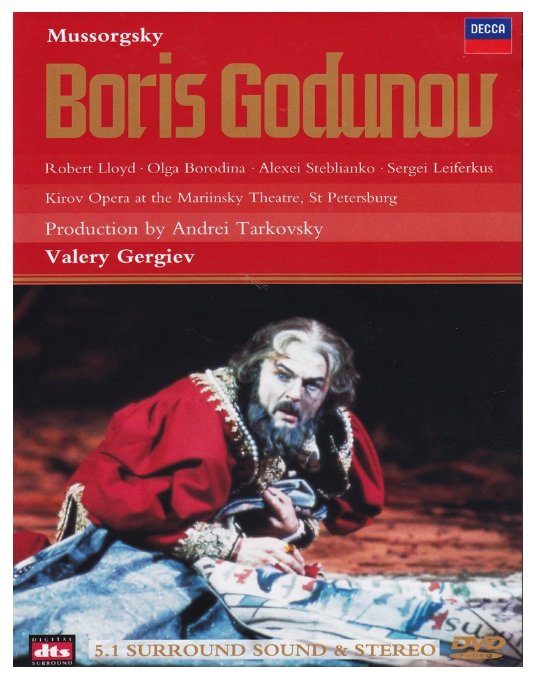

example is Boris Godunov.

I think it’s absolutely astounding opera. The more I do it, the

more I think it’s quite wonderful.

BD: Besides

the title character, have you also sung Pimen and Varlaam?

RL: No.

I studied Pimen and understudied it once at Covent Gardens. I got

to know him quite intimately. Varlaam doesn’t really interest me

at all. It’s not the sort of thing I do.

BD: It’s got

a fun song.

RL:

Yes. [Both laugh] It puts me in mind of a famous bass at

Covent Garden. I don’t know if he ever sang here — David Ward.

BD: We know

of him, but he never sang here.

RL: He was a

splendid gentleman, a really much-loved singer. I remember one

day he was asked to sing Rocco in Fidelio

by the conductor Joseph Krips, and his reaction was very

characteristic. He said, “What, me play a peasant???” [Both

laugh]

BD: He was

all nobility.

RL:

Yes. Basses tend to fall into that frame of mind, you know.

Anything less than a king is a bit in for a dig. No, the only

person that did those three roles was Boris Christoff. He created

a kind of precedent that nobody could quite live up to because he only

did it on record. He didn’t do it in real life.

BD:

Right. Occasionally, for instance, the American bass Paul Plishka

alternates. Some nights he’ll sing Boris and some nights he’ll

sing Pimen.

RL: It suits

him to do that, but I don’t. I don’t fancy myself as Pimen

really. Perhaps one day when I’m genuinely old — as

opposed to just fifty, nearly fifty-one — I

might be interested in Pimen. But once you’ve played Boris, I

think Pimen must be pretty uninteresting.

BD: Boris has

those five wonderful scenes, huge scenes on the stage.

RL: Yes, but

what I was thinking about him was that in a sense he’s not an accurate

portrayal of a historical character either. His historical

evolution on the operatic stage has distorted the nature of Boris

Godunov quite a lot. The Chaliapin-esque tradition, pursued by

Boris Christoff of making him into some sort of extraordinary ogre with

a big, black beard, is not in any sense historical accuracy. Nor

in fact do I find it very accurately representing Mussorgsky’s

music. Mussorgsky makes him a much more sensitive character than

the Chaliapin tradition makes him. Boris was a very great

man. I think the analogy between Boris Godunov and Gorbachev is

fabulous. It makes fascinating study! I went this year to

Leningrad to sing Boris with the Kirov Opera.

BD: Were you

accepted?

RL: Well, I was

obviously very nervous. I didn’t know how they would accept me

because I went as a bit of a package deal with the Tarkovsky production

of Boris, which we did at

Covent Garden. I don’t know whether Andrei Tarkovsky’s a known

character in the States, but he’s an icon. He’s a real saint in

Russia now, and he’s the doyen, really, of art movies throughout

Europe. He developed a style of art movie. I’m a little out

of my depth when talking about art movies, but it’s extremely literary

and poetic. It shows scant interest in the normal conventions of

cinema, like moving the plot along, or having clearly identified

characters and so on. What he tries to do is to paint almost

abstract paintings, or write obscure, abstract poetry on the

screen. It’s an extraordinary achievement, very compelling.

RL: Well, I was

obviously very nervous. I didn’t know how they would accept me

because I went as a bit of a package deal with the Tarkovsky production

of Boris, which we did at

Covent Garden. I don’t know whether Andrei Tarkovsky’s a known

character in the States, but he’s an icon. He’s a real saint in

Russia now, and he’s the doyen, really, of art movies throughout

Europe. He developed a style of art movie. I’m a little out

of my depth when talking about art movies, but it’s extremely literary

and poetic. It shows scant interest in the normal conventions of

cinema, like moving the plot along, or having clearly identified

characters and so on. What he tries to do is to paint almost

abstract paintings, or write obscure, abstract poetry on the

screen. It’s an extraordinary achievement, very compelling.

BD: So

transforming all this to opera is right up his alley?

RL: Quite,

yes. Boris is the only

opera he ever produced, and we were very lucky to be there because he

died two years later. Once he was dead he became a real

icon. When Gorbachev came along in the Soviet Union, Tarkovsky

was reinstated as a great Russian hero, having been exiled for most of

his working life. He was given the Order of Lenin and turned into

a great hero posthumously. As a part of that process, they

decided to take his production of Boris

Godunov to Leningrad from Covent Garden, and I went with

it. Only me, nobody else. It was all the Leningrad people

except for me, and that was pretty, pretty daunting thing to do.

But they accepted me. I was overwhelmed with it. It was

beautiful. The opera was going to be toured around Russia after I

finished with it, so there were five casts there all watching the

rehearsals. There were five Borises, sitting there with their

leather blousons and their arms folded, watching me. [Both

laugh] But I was really overwhelmed with the response. Each

of them came up to me and made quite long, generous speeches of

praise. I was really touched by it. It was

extraordinary! In London, the style that I was working in that

Tarkovsky had got out of me is something largely unknown in the Soviet

Union. They still act in a rather stylized, conventional

fashion. They strike poses on the stage. They sing to the

front. They seem rather stilted and old fashioned in the way they

perform, which is terribly surprising when you consider that

Stanislavski was a Russian, and Chaliapin, upon whom Stanislavski based

an awful lot of his writings, was also Russian. Yet somehow

they’ve got ossified in their acting style, and they were very, very

surprised and very excited by what we were offering them. So I feel

quite pleased with all that. That was great. I was most

afraid, of course, that my Russian pronunciation wouldn’t pass muster,

but it did.

BD: I was

going to ask you if you touched up your pronunciation, or made a few

little corrections as you heard things.

RL: I did a

lot of work on it, actually. The trouble is you only have one

life, and you have to work. Being an English speaker —

and you Americans have the same problems — we

haven’t any native opera, so we’re always performing in foreign

languages. Life for the Italians must be an absolute breeze, as

you say, or doddle, as we would say. [Both laugh] They go

around singing in their own opera in their own language in their own

style and are made into great stars. We have to sweat away at all

these languages, and life’s too short to do them all properly. So

you cut corners, and it was Russian that I cut the corner on. So

I was doubly anxious when it came to going to Leningrad, but apparently

I was fine.

BD: If the

populous could understand your words, then you’re all set.

RL:

Yes. In fact there was speculation in the press as to whether I

had a Russian mother, so I’m proud of that.

BD: You’re

making the analogy with Boris and Gorbachev. Would it be wrong to

build a production around that idea and have Boris with the little mark

on the head?

RL: Oh yes,

sure. Actually, let’s go back to that because that’s quite an

interesting line of thought. I had noticed the analogy with

Gorbachev some years before, but I’d kept it all to myself. Then

I worked on Boris in Amsterdam with a director called Harry Kupfer, and

he mentioned it en passant as

an idea. So I explored the idea a bit more. But when we got

to Leningrad and did our performance of Boris, it became very clear who

this man was. He wasn’t an old fashioned ogre with a black beard;

he was a man really struggling to try and rule his country with a

sensitive imagination and creative political skills. People

immediately noticed it. The Russians saw it. They said, “My

God, this is Gorbachev!” Then the analogies became very

clear. Boris says that he’s been in power for several years and

everything was okay, but then suddenly, everything went wrong.

There was a problem in Lithuania, Boris says. There was a problem

in Poland. Then there was pestilence, and you could read

Chernobyl for pestilence. Then there was famine, and if you talk

about food shortages and distribution problems, you’ve got

famine. Then you’ve got religious uprisings, and throughout the

Soviet Union now there are problems with ethnic religious groups like

the Muslims. So you’ve got in the opera Boris Godunov a portrait of Russia

— not then, but always. It’s a very, very fascinating

subject.

BD: I wonder

if there’s someone in the politburo

now who is a real Shuysky, who is going to come in and take over.

RL: Well, for

Shuysky, read Yeltsin. Hmmm? N’est-ce pas? [Both

laugh] It’s fascinating. When I was there, Gorbachev was in

the middle of a big political crisis which, in the west, nobody knew

about. Being in Russia we could see it happening. People

were glued to their television sets throughout Leningrad, just as we

were last week with the beginning of the Gulf War. Everybody was

going home and switching on to find out what would happen. That was

happening in Leningrad because there was a political crisis which none

of us understood. They wouldn’t explain it to us, but there was

some talk of corruption in high places. I saw Gorbachev make a

speech which went on for hours. He spoke extemporaneously —

apparently without notes, brilliantly! I couldn’t understand what

he was saying, but he looked so capable and competent and, quite

honestly, brilliant. He was confronted with a huge hall full of

the most grim-faced people imaginable. They were exactly the

Boyars that I knew from Boris Godunov.

For me it was a riveting experience.

BD: We have a

Leningrad connection here in Chicago. The Chicago Symphony and

the Leningrad Philharmonic did a swap earlier this season.

Leningrad came here and Chicago went there.

BD: We have a

Leningrad connection here in Chicago. The Chicago Symphony and

the Leningrad Philharmonic did a swap earlier this season.

Leningrad came here and Chicago went there.

RL: Oh,

that’s very good, yes.

BD: Have you

recorded any of Boris?

RL: Again, it

was a great stroke of fortune for me. The BBC decided to take an

interest in this trip to Leningrad, and they sent an outside broadcast

unit. Several great big wagons drove all the way to Leningrad,

and they relayed the first performance live to London and to the whole

of Europe and to the whole of Russia. It was also recorded and it

will be issued as a laser disc and a videocassette. It’s coming

out fairly soon, so it’ll be available in the shops.

BD: Will

there be a purely audio version also?

RL: Yes, and

there is some move afoot to broadcast it on PBS. I don’t know

whether that’ll happen, so that’ll be nice. Last year was a good

one for me because I also did Bluebeard’s

Castle of Bartók.

BD: On stage

or in concert?

RL: This was

a film. The best opera I’ve ever taken part in is Boris Godunov. The best opera

I’ve ever seen is Khovanshchina,

also by Mussorgsky. I think it’s absolutely brilliant. It’s

like a giant essay on historicism. It’s really wonderful.

Then Bluebeard. It is

just so psychologically fascinating. I was very fortunate the BBC

made a film of it which was directed by Leslie Megahey, the head of

music and arts. He did very well with it. He won the

biggest European television prize, the Prix Italia, for it. So

that went down very well, and that’s also going to be issued on video

here sometime in the future, I believe.

BD:

Good. We’ll look forward to that. I’m afraid I just wait

for the fifth door and those huge C-major chords.

RL:

Yes. [Laughs]

BD: It’s the

loudest thing I’ve ever heard in Orchestra Hall, and I’ve heard

Bruckner and Mahler and Wagner there! It just blew me away.

RL: Yes, it’s

wonderful. The one that I like best is the watery one.

BD:

Ah... bloop, bloop.

RL: Bloop,

bloop! Yes, that’s right. [Laughs] It’s a piece which

is eternally fascinating, very much the married man’s opera, I

think. What you do with that last scene, really, determines your

approach to the opera. Our producer decided that Bluebeard was,

in fact, a kind of collector. He had them almost, as it were,

skewered to the wall like butterflies.

BD: Stuffed

and mounted?

RL: Yes,

that’s the sort of image. They were very beautiful images, rather

after the style of Klimt. If I were put to it, I would probably

say that I didn’t agree with that ending, but I then I wasn’t put to

it. I think it’s more psychological than that.

*

* *

* *

BD: You are

here in Chicago singing Sarastro, so tell me the secret of singing

Mozart.

RL: My

goodness! I don’t think that singing Sarastro is singing Mozart,

really. Sarastro is an exception. Sarastro is very

difficult to sing well. It’s one of the most difficult of the

Mozart roles for anybody to be convincing in.

BD: Why?

RL: It’s one

of the most difficult ones to cast adequately because it requires

something which most Mozart singers are not required to do —

good old fashioned Italian bel canto. Basses are not

often asked to do that, especially on the low notes. I think the

only way to sing Sarastro is totally bel

canto, and I discovered that by listening to Ezio Pinza.

He sang it in Italian, which it makes it much easier. The problem

with German is you’ve got so many consonants; how to get around in a

word like nicht — there’s

not a lot of vowels in there. There’s an awful lot of consonants,

and to get seamlessly from one vowel to another, as you have to in bel canto, takes an awful lot of

work, an awful lot of practice. You have to be a very dedicated

Sarastro singer to actually master it. Most basses that I know

hate singing Sarastro because it seems terribly exposed. There’s

nowhere to hide. You can’t cover up a bit of phlegm with a bit of

heavy acting.

BD: Is it a

grateful role to sing, though?

RL: It

depends on how well you sing it. [Both laugh] That’s the

truth of the matter. You can’t act your way out of trouble.

If you don’t sing it well, they don’t clap so much. If you sing

it well, then they clap very well. It’s a frightening role to

perform, and it never stops being so. I’ve sung it many, many

times now. I’ve probably sung is more than anything else, and it

never gets any easier. One gets better at it, probably, but it

doesn’t get any easier.

BD: Is it

particularly difficult to go from singing to speaking?

RL: That doesn’t

help matters, no, certainly, because to project, especially in a house

the size of your American houses, you do have to speak extremely

strongly. You also have to pitch the voice very high in the

tessitura in order to carry. All the greatest big voices,

speaking voices, have been tenors. I did a radio program once

about the way people use their voices professionally in non-singing

ways. I talked to evangelists and sergeant-majors — you call them

Drill Sergeants — and politicians and

people like that, all people who professionally use their voices.

The conclusion that I came to was that most of the greatest speaking

voices for public oratory without microphones were tenors. They

had a tenor level of projection because in the old days they had to

project extremely far. There are references to John Wesley, the

great British evangelist, talking to thirty-two thousand people, which

is really, really incredible! I spoke to the most famous open-air

evangelist in England, Donald Soper, Lord Soper, who has been preaching

on Tower Hill in the center of London for fifty years now every Sunday,

in the open air. I asked him how many people he could speak to in

the open air and be heard, and he said a densely packed thousand,

perhaps. He boasted at the size of his voice. So what John

Wesley was like, God knows. [Laughs]

RL: That doesn’t

help matters, no, certainly, because to project, especially in a house

the size of your American houses, you do have to speak extremely

strongly. You also have to pitch the voice very high in the

tessitura in order to carry. All the greatest big voices,

speaking voices, have been tenors. I did a radio program once

about the way people use their voices professionally in non-singing

ways. I talked to evangelists and sergeant-majors — you call them

Drill Sergeants — and politicians and

people like that, all people who professionally use their voices.

The conclusion that I came to was that most of the greatest speaking

voices for public oratory without microphones were tenors. They

had a tenor level of projection because in the old days they had to

project extremely far. There are references to John Wesley, the

great British evangelist, talking to thirty-two thousand people, which

is really, really incredible! I spoke to the most famous open-air

evangelist in England, Donald Soper, Lord Soper, who has been preaching

on Tower Hill in the center of London for fifty years now every Sunday,

in the open air. I asked him how many people he could speak to in

the open air and be heard, and he said a densely packed thousand,

perhaps. He boasted at the size of his voice. So what John

Wesley was like, God knows. [Laughs]

BD: He was

thirty-two times bigger, obviously.

RL: Either

that or he wasn’t as honest as evangelists are supposed to be.

[Laughs]

BD: There was

a wonderful cartoon years and years ago in The New Yorker... Gandhi is

sitting there under his umbrella speaking to a huge throng and saying,

“Now can you hear me — you boys in the

back?” [To see that cartoon, click here.]

RL:

[Laughs] I spoke to a famous drill sergeant and he was clearly a

heldentenor; there was no doubt about it. He pitched the voice

right up really high. When speaking on a big stage here, a bass

has to raise the voice to the top part of the tessitura.

BD: How much

is projection and how much is focus?

RL: I think

they’re synonymous, really. If you have it fairly high in your

register and it’s beautifully focused, then it will carry. But

you do have to put a bit of force behind it, and you’re using force in

the high part of your voice. Then you’ve suddenly got to sing “O Isis und Osiris.” So the

speaking doesn’t help, in answer to your question.

BD: Do people

expect that Sarastro, with these wonderful low Fs, then to speak in a

round, low sound, and are they surprised when it’s high?

RL: I think

they are, yes. But quite honestly, you can’t be heard if you

mumble away [mumbles in German in very low register]. [Both laugh]

BD: Maybe we

should give you a throat microphone.

RL: Well,

that’s a thorny path, that is. I heard that Domingo was saying he

didn’t see why an opera singer shouldn’t from time to time be allowed

to use microphones. I think that’s a slippery slope, thin end of

a wedge, which I don’t want to get into because once you get into

microphones, then you lose some of the very basic elements of

opera. The athleticism of the sheer physical energy of

it, the sweat, and the color of an extended human voice is very

exciting.

BD: If it

were done with a real professional at the controls, but if it’s just

public address, then it won’t work at all.

RL:

Yes. I know in certain places they do use what they call

heightened sound, so that the ambience of the hall is more favorable to

the voices than it would otherwise be. I think that’s probably

okay. I’ll sort of accept that. [Laughs]

BD: This, of

course, leads us right into the question of recording. Can you

perform the same way in front of a microphone as you do in front of

four thousand people?

RL: No,

absolutely not. I’m not a friend of audio recordings. I

don’t like them at all.

BD:

[Surprised] And yet you have made a number of wonderful ones!

RL: Well, you

have to. That’s the way to a big career. The problem with

audio recordings is that the whole record industry has distorted my

profession a great deal by making the voices that are most in demand

not necessarily the personalities that are most interesting on

stage. Records also reduce the range of acceptable vocal

sound. Record companies seem to choose a particular type of voice

to record, and there are many other sorts of voice which are equally

valid, and not so listen to-able in a domestic context.

BD: Because

of their sound or their color?

RL:

Both. For instance, a singer like Jon Vickers in the later part

of his career had a voice of tremendous interest. [See my Interview with Jon

Vickers.] In the theater it was thrilling beyond

belief! You just couldn’t believe that he was doing some of the

things, but it was not a good voice to record in the later part of his

career. Such a shame that his excitement isn’t somehow available

to us. Voices for recordings seem to have a great deal of

refinement and clarity, and they mustn’t have rough edges and no phlegm

— many of the things that make any human voice really quite

interesting.

BD: Obviously

they’ve selected you, so you must fit into at least some of that

category.

RL: Yes, to

some extent. I’ve made a lot of recordings but there are many

more I would like to make. But I would much prefer to become a

well-known video performer rather than an audio performer because I

think it’s more valued as an artistic form. Once you’ve made a

record — after you go out there and sing it

through four or five times, sometimes a whole take, sometimes a few

bars at a time — then you have no control over

what happens. The recording engineer does everything else.

He balances the thing. He decides how loud you’re going to be,

how soft you’re going to be, how you’re going to stand out in an

ensemble. He can smother you with the orchestra if he wants

to. It’s an artifact of the recording engineer once you’ve done

your bit, so you have no artistic control over it at all, and I find

that very unsatisfactory. Whereas on video, if you’re out there

performing they can’t take that away from you. If they can see

what you’re doing, then nobody can take that away. Even that can,

of course, be edited in a way which can be helpful, but it can also be

upsetting. I noticed with the Boris

video that there were one or two moments which I was very proud of as

bits of internal acting, which were cut away from by the editor because

he’d seen something else on the stage which was more interesting.

So even then, you see, you don’t have control.

BD: Having

said that about recordings, are you basically pleased with the

recordings of your voice that have been issued?

RL: The

problem is that as soon as you’ve made a recording, you know you can

make it better because the experience of having made it qualifies you

to make it better. I don’t think many recording artists are

satisfied with anything they do. They would like to do it again

immediately. Stop! Hold the world! I want to do it

again. [Laughs]

BD: Then when

you’re finished with that, do it again-again!

RL: Yes, and

for five to ten years afterwards I find I can’t bring myself to listen

to them at all. I think, “Oh, God! Why didn’t I do

that?” But then, say ten or fifteen years later, you listen to it

and think, “Oh! That wasn’t too bad at all.” [Laughs]

Did I really sound like that?

BD: So you

have to have confidence in what you’re doing?

RL: Yes. You

just have to do it and take your money, and hope that it’s going to be

all right, really.

BD: Do you

enjoy it when people come backstage afterwards and say, “I liked your

performance, and I really like the recording”?

RL: Yes,

that’s nice. It is a great pity, though, that so much of an

operatic career is determined by recordings. It really is.

There’s no doubt at all that very few artists would sing at the

Metropolitan Opera unless they’d first made records. It’s the way

things are nowadays. It very often leads to poor casting, not

necessarily at the Metropolitan Opera, but in opera companies

generally. People are selected for their famousness through

recordings rather than for their ability to perform that particular

role.

BD: Do you

sing differently from house to house, depending on the size of the

house?

RL: Yes, I

think that is inevitable. Your American houses do create problems

for us, and of course the other way around. They create problems

for your American singers, too. One of the things that we tend to

notice about American singers when they come to Europe is that their

vocal style is somewhat more grandiloquent than the Europeans.

It’s quite clear once you’ve sung in one of these opera houses why

that’s so. You do have to belt it out, not to put too fine a

point on it. You have to actually push out the sound in as great

a quantity as you can to impress an audience as big as that.

BD: And yet,

you don’t have to push and strain.

RL: Oh,

no. Certainly not. But in a house like Covent Garden it

really feels very intimate. You can do almost anything you like

with the voice there. You can sing incredibly small.

BD: How many

seats are there?

RL:

2200. In fact most of the bigger European opera houses are about

the same size — Paris, Vienna, Munich, Berlin,

London. Leningrad was a bit smaller, but I think the Bolshoi is

about the same.

BD: Our

houses then are nearly twice that size.

RL:

Yes. In actual internal space — cubic

capacity — they’re almost certainly twice the

size of most of those houses. In terms of audience capacity,

maybe half again, but in order to get that amount of audience in you’ve

got to have more actual area. So they do seem enormous. The

only places I’ve sung in bigger than the American ones are in Seoul,

Korea. It’s an absolutely gigantic place!

BD: Have you

sung in open air, like in Orange?

RL: Not in

Orange. I’ve sung in Aix-en-Provence, which is kind of half in

open air. You’ve got a cover to the stage, but the audience is in

the open air. I’ve sung in a park in San Francisco which was

really quite an experience, but I haven’t sung in Verona or any of

those big amphitheaters. I can’t believe it’s really too artistic

an experience. If there’s a thread to the way I select work, I

try to be sure that’s it is going to be as artistic as possible.

It’s not always possible in opera because people are interested in

things other than the art. They’re interested in volume; they’re

interested in personality; they’re interested in glamour; they’re

interested in wealth; they’re interested in social activity and social

display. All these things come into opera. But as often as

possible I choose something I think is going to be an artistic

experience though that’s not always possible.

*

* *

* *

BD: You’re a

bass and you are limited by the number of roles you can sing because of

the tessitura and the amount of range that you have, but are you

pleased with the characters that these roles offer you?

RL: I do feel

a bit limited sometimes, yes. I’m glad I don’t have to play the

tenor roles that are always the young lover. I think that would

be a very difficult thing to do especially as you get older. We

tend to say that basses become more relevant as we get older. We

put on less and less makeup as time goes by, and the tenors put on more

and more makeup as time goes by. That’s why they have such big

fees, you know, to pay for the makeup. [Gales of laughter all

around.] The baritones and tenors have some wonderful tunes, and

we could do with a few more tunes, us basses.

BD: Have you

ever been tempted to do a baritone-type role?

RL: I’ve done

Don Giovanni which is bordering on that territory, and apparently it

didn’t suit me very well. So my agent doesn’t look for

opportunities for me to do it.

BD: That’s

too bad. I’ve heard bases and baritones do Don Giovanni, and I

like the extra weight of the bass.

RL:

Yes. I quite enjoyed doing it, but it didn’t go down too

well. I’m constantly tempted by Wotan and I think probably I’ll

capitulate one of these days. But I had a very shrewd old agent

once who said, “Better to be a world famous bass than just another

Wotan.” I think there’s something in that. If you sing

Wotan and you’re really a bass, you can burn your boats, and there’s

really no way back then to cantabile bass singing, which is really what

I like doing.

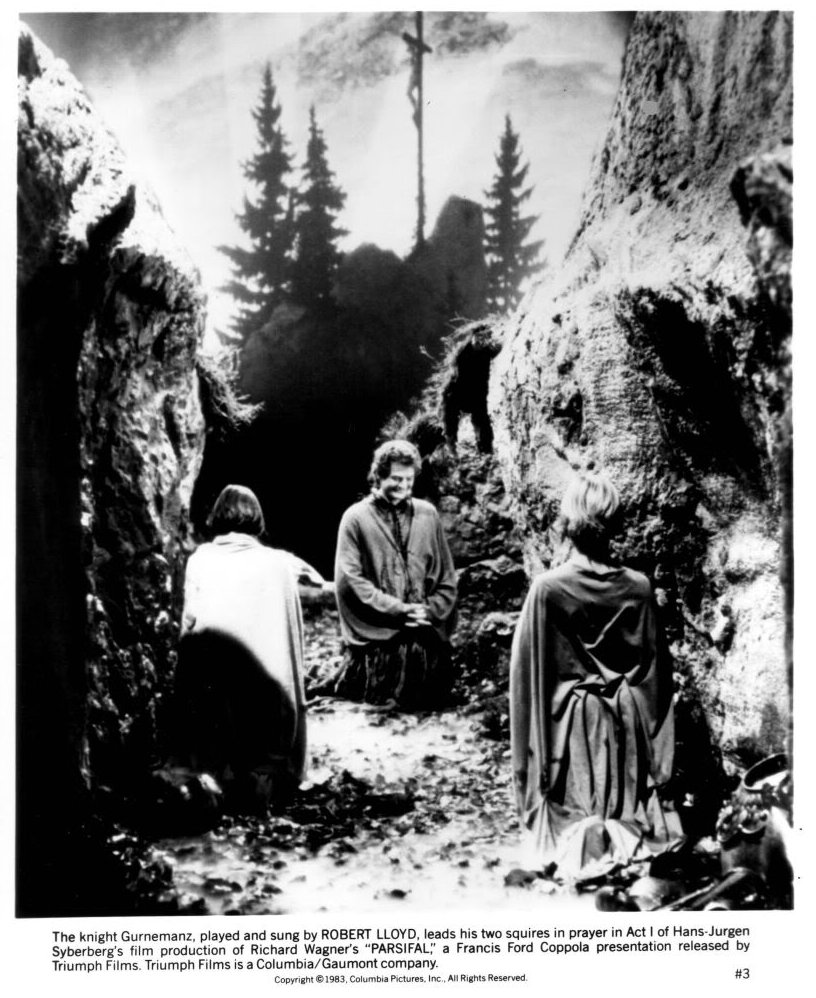

BD: Let’s stay with

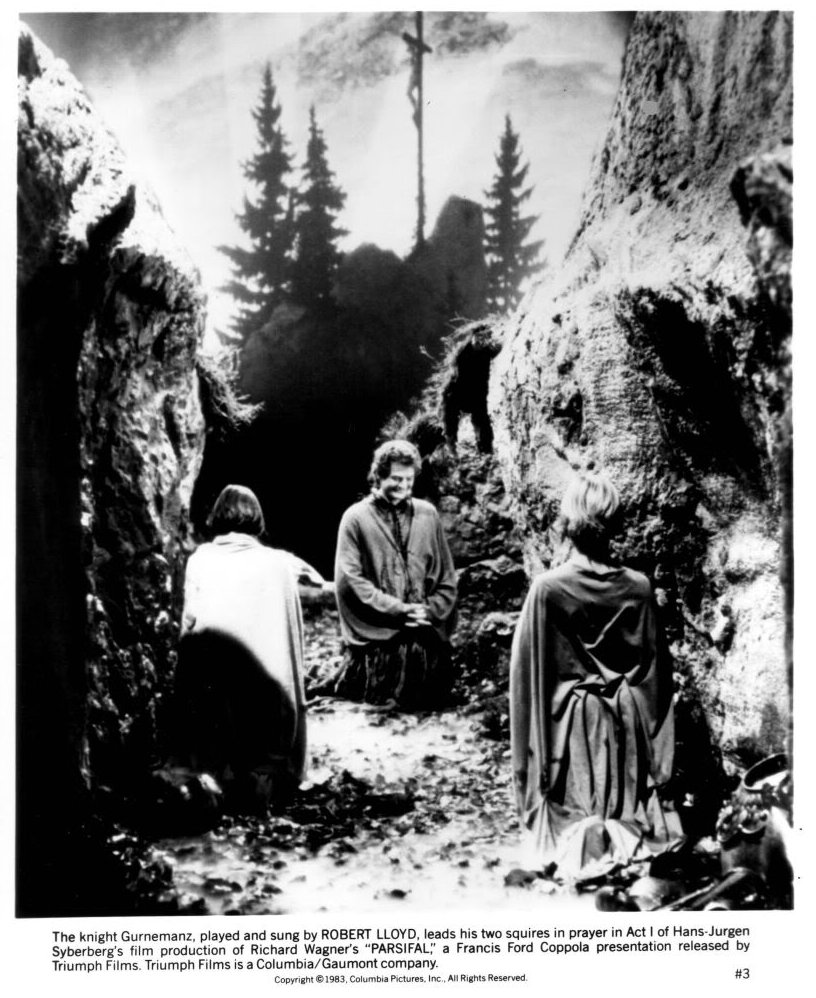

Wagner a little bit. You’ve sung Gurnemanz, so tell me a bit

about him.

BD: Let’s stay with

Wagner a little bit. You’ve sung Gurnemanz, so tell me a bit

about him.

RL: That’s my

next job at the Met, actually, to do Parsifal

with the new production. James Levine’s conducting, with

Plácido Domingo and Jessye Norman. It’s going to be quite

an occasion. [Ponders a moment] I’m not sure there’s a

great deal to say about Gurnemanz because he’s almost, in a sense, a

non-character. He’s more like a commentator or a voice off, in a

way, telling the story several times over. His own personality

doesn’t emerge very much in it at all. He’s an elderly man.

BD: How old

is he?

RL: I don’t

think it matters. He just has to register as elderly in

comparison with the other people around. I’ve seen pictures of

the very first Gurnemanz. He had a gigantic cotton wool beard

that came down almost to his waist.

BD: In the

first act, or just the third act?

RL: That I

don’t know. There is the passage of time, but I’m not sure that

chronology’s got too much to do with it. It’s more like the passage of

the spirit rather than the passage of actual chronological time.

But what is interesting to talk about is the opera Parsifal, which in a sense is what

Gurnemanz is about, because Gurnemanz expresses the opera. He

tells the story. He sets the scene. He narrates what goes

on. Not actually a great deal happens in the opera.

Most has happened before and during interval, which Gurnemanz

explains. It’s a wonderful part to sing because there’s some

wonderful spasms of melody in it. You feel as you’re performing

it as though you’re afloat on a warm, rich, rather oily ocean of

sound. Especially the Good Friday music at the end is a wonderful

experience. You feel at the end of it totally spent because

you’ve been there and pouring out sound for an awfully long time.

It’s true catharsis. You’ve really purged yourself of your spirit

by then.

BD: Is the

work an opera or is it a sacred play?

RL: I spent a

lot of time thinking about it before I performed it first. I

thought that I ought to turn up to the first rehearsal with some ideas

about it. Probably that was a mistake, because it meant that I

had to spend an awful lot of time getting rid of my ideas and

recharging myself with the ideas of somebody else. But it was

fun. It was intellectual fun trying to work out what Parsifal was all about. It’s

a long time ago now. It’s difficult to reconstruct the stages

through which I went. I went through stages of trying to identify

with the characters in it. There were moments in it that I

absolutely recognized, that actually touched me right to the heart

— like the moment that Parsifal shoots the swan and

Gurnemanz tells him off. He says, “Why have you shot this swan

here, of all places, in this place where animals are sacred?” and

Parsifal suddenly understands what he’s done. It never crossed

his mind that it was wrong to shoot swans, but as soon as Gurnemanz

explains to him he’s cut to the quick. He realizes it and he

smashes his bow and throws it to the ground. I absolutely

identify with that because I went with my father shooting — what you

would call hunting — wildfowl, geese and ducks in the marshes of

Essex. It was a very beautiful, melancholy, exotic sort of thing

to be doing on those wild places, and I loved it. I loved the

experience of the early morning, and seeing the geese coming up over

the marshes. So I shot one and I couldn’t bear it! There

was this thing on the ground. It wasn’t quite dead, and it was

struggling and it was squawking and it was bleeding. I had to

kill it, finish it off with the butt of my rifle, and I hated myself

for doing it. It was a wonderful, exactly Parsifal moment in my life.

Then as time went on, I saw more and more moments like that in the

course of the opera that I could identify with. I thought, “Maybe

this is what Parsifal is

about. Perhaps what you have to do is to find yourself in the

opera.” So I pursued that line of thought for a while, but I

couldn’t tie it up. It didn’t come to any sort of conclusion in

my mind. Then I met a producer, Filippo Sanjust, a man of

extraordinary brilliance, who was the designer for a number of

Visconti’s operas and films. He never had the success as a

director that he had as a designer, but as a personality, as an

individual person, he was extraordinarily brilliant. And he said,

“Oh, Parsifal, that’s

easy. Everybody’s the same person in Parsifal.” That set me

thinking. Could it be that these various characters — Parsifal,

Kundry, Gurnemanz, Amfortas, Klingsor — all

these are aspects of one person? They’re elements of the

psyche? That’s an interesting idea. Then I had the

extraordinary fortune of making a film of Parsifal with Hans-Jürgen

Syberberg, the maverick German film producer. We discussed it a

lot, and one day at breakfast he said, “Of course, Wagner is Parsifal.” I said, “Do you

mean the character Parsifal is Wagner?” He said, “No, no.

Wagner is the opera.” That made very good sense to me and has

remained really, the core of my thinking about Parsifal ever since. In

actual fact, Parsifal is a

kind of artistic autobiography where Wagner traces the development of

his own search for his own personal grail, his really, and that was

artistic maturity, full artistic self-expression. It might be too

offensive, or you could suggest that the moment he kisses Kundry is the

moment he met Cosima. That the meeting with Cosima opened up the

most productive period in his life. In the film with Syberberg,

he did the very extraordinary thing after the kiss of changing the sex

of Parsifal. Parsifal was no longer a boy but now a kind of

slightly androgynous girl. So the suggestion there was that at

that point Wagner discovered his anima, that the truly creative,

lyrical element of his personality was discovered after he met

Cosima. Then he was able to complete The Ring and do Parsifal and all his mature things.

BD: When

Parsifal loses the boyhood and becomes, as you say, sort of partial

woman, does he lose his sexuality or does he gain more sexuality?

RL: In the

film, neither of them have a great deal of sexuality because in the

film you can use non-singers. I was fortunate that he chose me to

do the singing and the acting. That was, I think, simply because

he couldn’t find an actor willing to learn all that text and

synchronize with the music.

BD:

[Laughs] That’s right. For the Amfortas, they had the

conductor, Armin Jordan, act on screen. [See my Interview with Armin

Jordan.]

RL: Yes, that’s

right. That was a very shrewd move because the conductor knows

the text and he looked very much like an Amfortas. But he found

these two young people. [Photo

at left] I think he saw one of them in a restaurant and he

saw the other one in the street and he said, “I must have them for the

film.” The boy was actually a good deal older than he looked, but

he looked very unformed, terribly aesthetic... kind of beautiful but in

a rather shapeless way. It was much more like that on film than

he was in real life. And the girl had an asexual quality on film,

a blandness, a sort of nothingness in the face, which was faintly

reminiscent of one of those Renaissance Madonnas but not quite as

pretty as a Renaissance Madonna without expression. So the move

from the boy to the girl wasn’t as long a step as you might have seen,

but it was still pretty odd to hear Reiner Goldberg’s voice coming out

of a girl. [Both laughs] That idea of the opera being

Wagner was extended by the fact that the whole film took place on or

inside the head of Wagner. He’d constructed a gigantic death mask

of Wagner out of concrete and plaster which took up the whole of the

huge sound studio where we were working. It could be divided into

segments so that the chin could come away from the cheeks and the

cheeks could come away from the forehead and so on, making kind of

Grand Canyons in between these things so that people could move into

the head of Wagner and go into a completely different

environment. You could go into the side of Wagner’s face and

enter a woodland, some beautiful place.

RL: Yes, that’s

right. That was a very shrewd move because the conductor knows

the text and he looked very much like an Amfortas. But he found

these two young people. [Photo

at left] I think he saw one of them in a restaurant and he

saw the other one in the street and he said, “I must have them for the

film.” The boy was actually a good deal older than he looked, but

he looked very unformed, terribly aesthetic... kind of beautiful but in

a rather shapeless way. It was much more like that on film than

he was in real life. And the girl had an asexual quality on film,

a blandness, a sort of nothingness in the face, which was faintly

reminiscent of one of those Renaissance Madonnas but not quite as

pretty as a Renaissance Madonna without expression. So the move

from the boy to the girl wasn’t as long a step as you might have seen,

but it was still pretty odd to hear Reiner Goldberg’s voice coming out

of a girl. [Both laughs] That idea of the opera being

Wagner was extended by the fact that the whole film took place on or

inside the head of Wagner. He’d constructed a gigantic death mask

of Wagner out of concrete and plaster which took up the whole of the

huge sound studio where we were working. It could be divided into

segments so that the chin could come away from the cheeks and the

cheeks could come away from the forehead and so on, making kind of

Grand Canyons in between these things so that people could move into

the head of Wagner and go into a completely different

environment. You could go into the side of Wagner’s face and

enter a woodland, some beautiful place.

BD: Sounds a

little bit like the Ring that

they did at Bayreuth in 1960, which was a disk. It started as a

disk and then broke apart into all kinds of pieces throughout the

cycle, and eventually at the end came back and was a disk once more.

RL: Oh,

yes. Same idea. It led to things like the Kundry, for some

reason at some stage is in a pool of water and the pool of water is in

the eye socket.

BD: Tears?

RL: Yes,

that’s right. The garden is obviously a very fragrant place full

of flowers, and that’s just under the nostrils. It’s a difficult

film. People do find it difficult, but maybe anybody listening to

this might use what I’ve said as a key to understanding it a little

more.

BD:

Exactly. What other Wagner have you done? You’ve done the

Heinrich?

RL:

Yes. I do that fairly often. It’s not one of my

favorites. In the old days I did Fasolt in the Ring. I liked Fasolt very

much. I thought he was a lovely chap. He was the only

genuinely nice person in the whole of the Ring cycle.

BD: Then he

gets bopped off right away.

RL: That’s

right, yes. [Laughs]

BD: Was it

your choice or the producer’s choice to cast you as Fasolt rather than

Fafner?

RL: At the

time I think it was inevitable that I would be Fasolt because my voice

tended to be lyrical, and for Fafner you had to be able to bark.

We had Matti Salminen as the logical choice there because he’s such a

wonderful, dark, strong bass. He was tremendous;

awe-inspiring! As for other Wagner, I do Daland in The Flying Dutchman. I do

that quite a bit, too.

BD: Is Daland

a nice fellow or is he just an opportunist?

RL: I worked

it out with a producer in Munich. Unfortunately, I’ve forgotten

his name — very, very creative thinker. We thought that Daland

was probably not a very nice man. He was really much too

interested in the money. He didn’t ask anything like enough

questions as to who this man, the Flying Dutchman, was, and he was

prepared to trade his daughter for the money really too quickly.

BD: There’s

nothing on the other side — that the daughter’s

been around just a little too long and Daland has seen her be just a

little bit too neurotic?

RL:

[Laughs] I think so, yes, but in that production it was done very

much as though it were inside the psyche of Senta. So she was

presented as a girl who was totally dominated and obsessed with her

father’s world. Her whole world was full of pictures of ships and

ships and seamen and ropes and all that, so when she saw this seaman,

this ultimate seaman arriving, she immediately fell in love with this

replacement for her father. So Daland was played as a very

dominant and domineering father. I like to think of him rather as

that Shakespearean character who could smile and smile and still be a

villain.

BD: Do you

sing Wagner differently than the Verdi characters or Mozart characters?

RL: I try to

sing as much as possible always the same way. With Daland I allow

a certain roughness to come in during the first scene, but as much as

possible I like to try and sing bel

canto. I’m sure that’s what Wagner wanted. I’m sure

that’s how Wagner perceived all his roles, with bel canto singing.

Unfortunately all these things have come to be performed with

orchestras which are much too large, in opera houses which are much too

big, and with conductors who want to build their reputations upon the

loudness of their singers’ voices. The whole thing’s become an

awful competition for loudness.

BD: Is there

any hope?

RL: Not a

lot. I think Wagner is going to go on ruining tenor voices.

He doesn’t do quite so much damage to basses, but he does a lot of

damage to bass-baritones. If only they could find an environment

which they could sing more gently. Mind you, I have sometimes

wondered what sort of genius he was, who gave all that music to tenors

in that tessitura.

BD: He

thought of them as characters rather than as human beings. The

Siegfried character as being just Siegfried, rather than a tenor who

has to sing it.

RL: Yes,

yes. I must say, it’s very nice to hear Domingo singing the Lohengrin. I did it with him

in Vienna recently and I look forward to the Parsifal because to hear an

Italianate sound on the Wagner is really good. I sometimes think

that Wagner’s used as an excuse for lazy singing by some singers.

It falls into the hands of singers who don’t try hard enough at singing

bel canto. You hear

someone like James Morris, who all his life sang as a lyric bass and

then suddenly becomes a Wotan, and you hear magnificent Wagner singing

without any sense of that Bayreuth bark. That’s beautiful,

wonderful singing.

BD: You said

you are thinking of essaying Wotan at some point?

RL: I might,

yes.

BD: One or

all three?

RL: All

three. I could do the Rheingold

with no problem at all, straight away. The difficult one is the Siegfried. But we’ll see how

it goes. I do most composers, really, from time to time.

One area which I’ve always wanted to do more of is the early

music. There’s a lot of very good bass stuff written by

Monteverdi and Cavalli and people like this... beautiful, beautiful

bass singing.

BD:

[Contemplating the early works] You’d be a terrific Seneca.

RL: Yes, I

did Seneca. That also is available on videocassette from

Glyndebourne. I enjoyed Seneca enormously. I also did

Neptune in Ulysses by

Monteverdi at Glyndebourne. That also is on cassette, and there’s

a lot of Purcell which I would like to have a go at. There are

some beautiful Purcell songs. Unfortunately we get

pigeon-holed. People think, “Oh, he sings Wagner or Verdi with

the occasional Zoroastro.” Then they think, “Well, he wouldn’t be

interested in Monteverdi.” But I am! I would very much like

to do that. Also there comes a time when they think you sing too

loud for those ancient instruments. But that’s not necessarily

so. I can sing quietly. [Laughs]

BD: One last

question. Is singing fun?

RL: It’s

interesting you should ask that question. I did a radio program I

spoke of earlier, about the way people use their voices. I was

interested in why people sing. I wondered if any research had

been done into what makes people sing. I wrote to the professor

of psychology at Oxford University and asked him. He wrote back

and said that as far as he knew there wasn’t any research on that

subject, but people had researched why birds sing. Birds sing,

apparently, for three reasons. One is for sexual display, the

second is for territorial advantage — marking

out their territory — and the third is for the

hell of it, because it’s fun. [Laughs] In answer to your

question, singing is all those three things at various times in one’s

career and at various times in one’s life. I don’t think any

great singer would be a great singer unless they were, at some stage in

their career, interested in the sexual display element, and a lot of

them go on being interested in that right through their careers.

The territorial advantage is represented in terms of money and travel

and the power and fame that it gives. But the for-the-hell-of-it

element, the fun element, has got to be there, otherwise I don’t think

you’re a genuinely interesting singer. I’ve found that it’s got

more fun as time goes on because the other two have become less

important as I’ve got older. Recently I was taking part in a sitzprobe. That’s when the

singers first meet the orchestra, and you go through it sitting down,

stopping and starting and doing the difficult bits several times.

That’s the time that the singers actually hear the orchestra most

intimately. You’re sitting there right in the middle of the

orchestra. You’re right in the middle of this music! You’re

not on the stage, only half hearing it; you’re caught up right in the

middle of it, and that’s when it’s at its most exciting. All

singers like the sitzprobe.

It’s the best time, and many times recently I’ve had the feeling that

I’m really very privileged to be there in the middle of this

music. This is not given to everybody to do this. You know,

I’m not as young as I used to be. I’m not going to be able to do

this forever, so I’ve got to enjoy this. I’ve really got to take

this and relish it. So it has become, in a sense, more... “fun”

is perhaps not absolutely the right word, but I certainly do it more

for the hell of it than I used to.

BD: I

hope you keep doing it “for

the hell of it”

for a long time.

RL: Oh, thank

you.

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at his apartment in

Chicago on January 22, 1991. Sections were used

(along with

recordings) on WNIB two months later (during the broadcast of his Parsifal on Easter Sunday), also in

1995 and again in 2000.

It was transcribed

and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

BD: Do you sing him?

BD: Do you sing him? RL: Ah well, people

vary on that. My family tend to think I become the character, but

I like to think I portray it. I don’t know whether everybody has

to work this way in order to get a good result, but the way I work is

that I have to find the character. I have to find the personality

in myself at some stage during rehearsals. King Philip I always

think of as a tyrant who is a tyrant because he’s fundamentally a

wimp. He lashes out at everything in a rather uncontrolled

fashion because he deeply distrusts his own real inner core. So I

look for those characteristics in myself and write it out from

there. By the time I arrive on the stage for the first night,

I’ve discovered this character. I’ve photocopied him, as it were;

I can reproduce him at will. But I don’t think at the time, on

the stage on the first night, I’ve been King Philip. I’m doing a

duplicate version of something I discovered in rehearsal.

RL: Ah well, people

vary on that. My family tend to think I become the character, but

I like to think I portray it. I don’t know whether everybody has

to work this way in order to get a good result, but the way I work is

that I have to find the character. I have to find the personality

in myself at some stage during rehearsals. King Philip I always

think of as a tyrant who is a tyrant because he’s fundamentally a

wimp. He lashes out at everything in a rather uncontrolled

fashion because he deeply distrusts his own real inner core. So I

look for those characteristics in myself and write it out from

there. By the time I arrive on the stage for the first night,

I’ve discovered this character. I’ve photocopied him, as it were;

I can reproduce him at will. But I don’t think at the time, on

the stage on the first night, I’ve been King Philip. I’m doing a

duplicate version of something I discovered in rehearsal. RL: Well, I was

obviously very nervous. I didn’t know how they would accept me

because I went as a bit of a package deal with the Tarkovsky production

of Boris, which we did at

Covent Garden. I don’t know whether Andrei Tarkovsky’s a known

character in the States, but he’s an icon. He’s a real saint in

Russia now, and he’s the doyen, really, of art movies throughout

Europe. He developed a style of art movie. I’m a little out

of my depth when talking about art movies, but it’s extremely literary

and poetic. It shows scant interest in the normal conventions of

cinema, like moving the plot along, or having clearly identified

characters and so on. What he tries to do is to paint almost

abstract paintings, or write obscure, abstract poetry on the

screen. It’s an extraordinary achievement, very compelling.

RL: Well, I was

obviously very nervous. I didn’t know how they would accept me

because I went as a bit of a package deal with the Tarkovsky production

of Boris, which we did at

Covent Garden. I don’t know whether Andrei Tarkovsky’s a known

character in the States, but he’s an icon. He’s a real saint in

Russia now, and he’s the doyen, really, of art movies throughout

Europe. He developed a style of art movie. I’m a little out

of my depth when talking about art movies, but it’s extremely literary

and poetic. It shows scant interest in the normal conventions of

cinema, like moving the plot along, or having clearly identified

characters and so on. What he tries to do is to paint almost

abstract paintings, or write obscure, abstract poetry on the

screen. It’s an extraordinary achievement, very compelling. BD: We have a

Leningrad connection here in Chicago. The Chicago Symphony and

the Leningrad Philharmonic did a swap earlier this season.

Leningrad came here and Chicago went there.

BD: We have a

Leningrad connection here in Chicago. The Chicago Symphony and

the Leningrad Philharmonic did a swap earlier this season.

Leningrad came here and Chicago went there.  RL: That doesn’t

help matters, no, certainly, because to project, especially in a house

the size of your American houses, you do have to speak extremely

strongly. You also have to pitch the voice very high in the

tessitura in order to carry. All the greatest big voices,

speaking voices, have been tenors. I did a radio program once

about the way people use their voices professionally in non-singing

ways. I talked to evangelists and sergeant-majors — you call them

Drill Sergeants — and politicians and

people like that, all people who professionally use their voices.

The conclusion that I came to was that most of the greatest speaking

voices for public oratory without microphones were tenors. They

had a tenor level of projection because in the old days they had to

project extremely far. There are references to John Wesley, the

great British evangelist, talking to thirty-two thousand people, which

is really, really incredible! I spoke to the most famous open-air

evangelist in England, Donald Soper, Lord Soper, who has been preaching

on Tower Hill in the center of London for fifty years now every Sunday,

in the open air. I asked him how many people he could speak to in

the open air and be heard, and he said a densely packed thousand,

perhaps. He boasted at the size of his voice. So what John

Wesley was like, God knows. [Laughs]

RL: That doesn’t

help matters, no, certainly, because to project, especially in a house

the size of your American houses, you do have to speak extremely

strongly. You also have to pitch the voice very high in the

tessitura in order to carry. All the greatest big voices,

speaking voices, have been tenors. I did a radio program once

about the way people use their voices professionally in non-singing

ways. I talked to evangelists and sergeant-majors — you call them

Drill Sergeants — and politicians and

people like that, all people who professionally use their voices.

The conclusion that I came to was that most of the greatest speaking

voices for public oratory without microphones were tenors. They

had a tenor level of projection because in the old days they had to

project extremely far. There are references to John Wesley, the

great British evangelist, talking to thirty-two thousand people, which

is really, really incredible! I spoke to the most famous open-air

evangelist in England, Donald Soper, Lord Soper, who has been preaching

on Tower Hill in the center of London for fifty years now every Sunday,

in the open air. I asked him how many people he could speak to in

the open air and be heard, and he said a densely packed thousand,

perhaps. He boasted at the size of his voice. So what John

Wesley was like, God knows. [Laughs] BD: Let’s stay with

Wagner a little bit. You’ve sung Gurnemanz, so tell me a bit

about him.