|

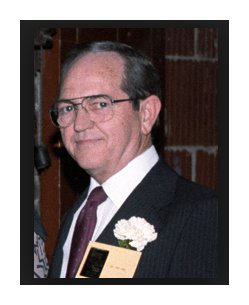

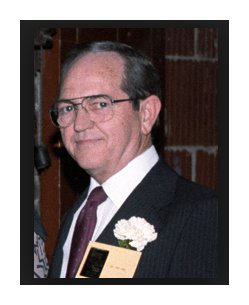

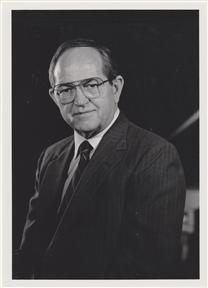

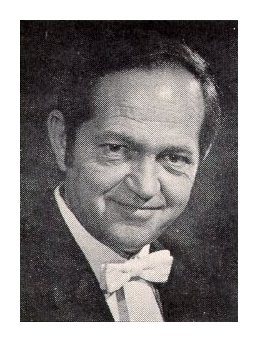

RAY E. LUKE Ray E. Luke, 82, passed away Wednesday after a brief

illness. Born in

Fort Worth, Texas on May 30, 1928, Luke was the son of Ray H. and

Dorothy Luke. At an early age, he demonstrated a talent for music and

played trumpet in many area ensembles. Luke earned bachelor's and

master's degrees in music from Texas Christian University. He taught

briefly at Atlantic Christian College in Wilson, N.C. and then returned

to Texas as a music faculty member at East Texas State College. During

his 13-year career at East Texas, he developed a flair for arranging

that led him to make his first efforts at composition. In 1957, Luke

was accepted at the University of Rochester's Eastman School of Music

where he studied composition with Bernard Rogers. Luke earned his Ph.D.

in composition in 1960. In 1962, Luke joined the faculty at Oklahoma

City University, where he became chairman of the instrumental music

department. A year later, Luke became music director of the newly

created Lyric Theatre and conducted there for five seasons. In the late

1960s, Luke became associate conductor of the Oklahoma City Symphony

Orchestra. Upon Guy Fraser Harrison's retirement in 1973, Luke served

as music director of the orchestra for one season. Harrison premiered

the majority of Luke's orchestral works, a practice continued when Luis

Herrera de la Fuente became music director. During a compositional

career that spanned more than 40 years, Luke composed more than 80

works for orchestra, band, chorus, opera, ballet and chamber music. In

1969, his piano concerto won the top prize in the Queen Elisabeth of

Belgium competition. In 1979, his opera "Medea," which featured a

libretto by Carveth Osterhaus, won the New England Conservatory Opera

Competition Award. Luke conducted the world premiere in Boston. Among

his other awards are the Oklahoma Musician of the Year (1970), the

Distinguished Alumnus of TCU (1972) and the Oklahoma Governor's Arts

Award (1979). For more than 25 consecutive years, Luke was honored by

the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. The ASCAP

Award is presented for outstanding work in the area of serious music

composition. Luke's legacy as a composer and his influence on countless

student musicians are a tribute to his tireless efforts to make the

finest music possible. After 35 years at OCU, Luke retired in 1997. He

was preceded in death by his parents and his sister Helen Osier. He is

survived by his wife of 58 years, Faye, daughter Lisa and husband Matt

Mayfield, son Jeff and wife Kim, grandchildren Lauren, Justin and

Madison Mayfield, Jason and Jessie Luke, four nieces and a nephew. The

family will receive guests at the funeral home from 6 to 8 p.m. today.

Services will be at 10 a.m. Saturday at the Spring Creek Baptist

Church, 11701 N. MacArthur with interment in Rose Hill Burial Park.

Memorials may be made in Ray Luke's name to the OCU School of Music

Scholarship fund. Arrangements under the direction of Hahn-Cook/Street

& Draper Funeral Directors, Oklahoma City, OK.

-- Published in "The

Oklahoman" on September 17, 2010

In addition to the details listed

above, here are a few more from another source . . . . .

Ray Luke is

nationally significant as a composer of

contemporary classical music. The hallmark of his highly original work

is a distinctive and unusual combination of techniques and styles. He

composed prolifically, encompassing orchestral music and chamber pieces

as well as opera and ballet. His works include Dialogues for Organ and

Percussion, Sonics and Metrics for Concert Band, Plaints and Dirges for

Chorus and Orchestra, Prelude and March, and the ballet Tapestry. From

1960 through 1973 the Oklahoma City Symphony premiered seventeen of

Luke's works, including Piano Concerto and Compressions for Orchestra.

The Tulsa Philharmonic commissioned and premiered Third Suite for

Orchestra in 1989, and OCU commissioned Cantata Concertante in 1991. In

1995 OCU premiered two of Luke's one-act operas, Drowne's Wooden Image

and Mrs. Bullfrog, both based on stories by Nathaniel Hawthorne.

|

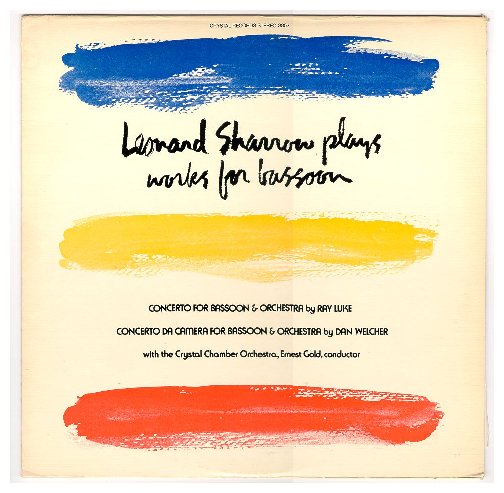

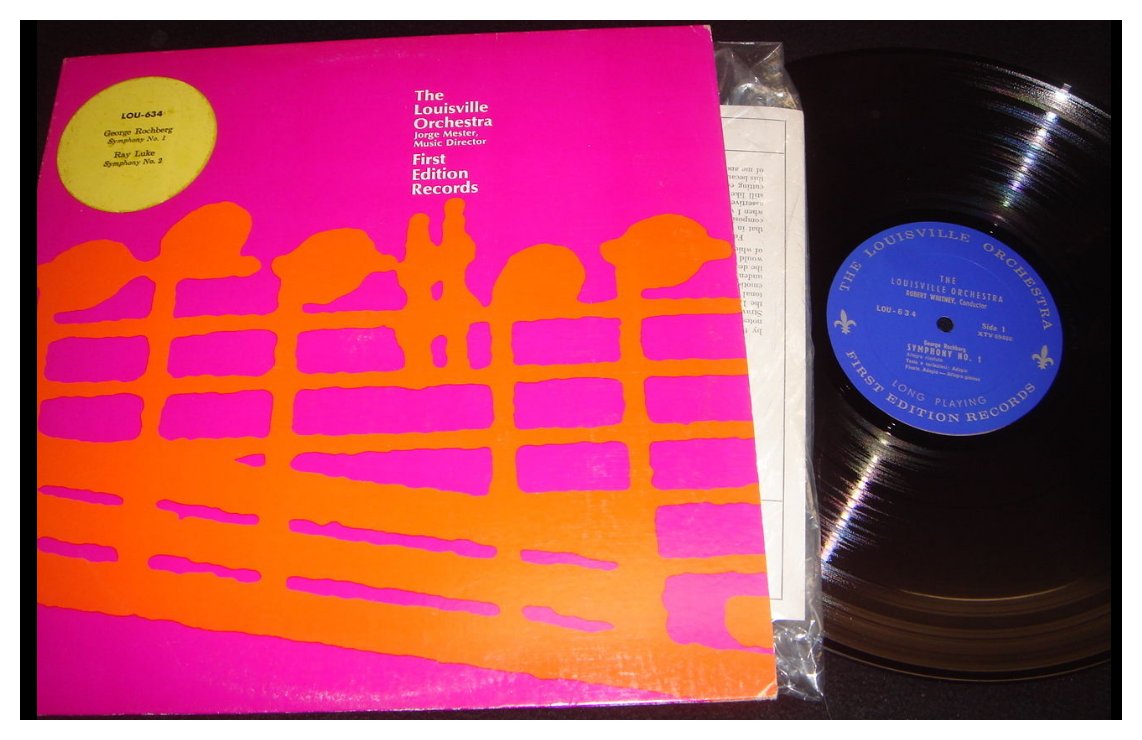

I bring this up because it was a recording of the Bassoon Concerto by Ray Luke which

piqued my interest in the composer. I had, of course, the LP

issue, with its professional but uninteresting cover (seen at left). The photo

farther down on this webpage shows a later edition on CD with an

appropriate cartoon depicted. I figured that if he had written

this delightful work for my favored instrument, he must be a nice

fellow. So I made contact with him in July of 1989, and my

assumption was proven very true.

I bring this up because it was a recording of the Bassoon Concerto by Ray Luke which

piqued my interest in the composer. I had, of course, the LP

issue, with its professional but uninteresting cover (seen at left). The photo

farther down on this webpage shows a later edition on CD with an

appropriate cartoon depicted. I figured that if he had written

this delightful work for my favored instrument, he must be a nice

fellow. So I made contact with him in July of 1989, and my

assumption was proven very true.  BD: Is there any chance that

maybe there is

simply too much new music around?

BD: Is there any chance that

maybe there is

simply too much new music around? RL: No, no. Well, it can

be taught to that

person who’s showing a first interest. He can be introduced to

all the many styles and possibilities. I remember when I started

to

try to compose, I had to find out what’s going on and what was there

available to me. I asked how could I write if I wanted to?

Which

could I choose? Where can I go to find something to choose for a

way to write? Some of those things can be taught, but

certainly just above that beginning level we’re

talking about a coach; someone who can encourage, someone who can

perceive difficulties or who can sense directions that need to be

taken,

can guide listening, and frankly, help develop the technique. It

is necessary that the composer have technique. He can’t just sit

down and start rambling in some way. That can be taught, but

certainly it’s a matter of guiding. You’re teaching always

through

the music that the student is composing. So he has to do his

writing and then be criticized and helped with it.

RL: No, no. Well, it can

be taught to that

person who’s showing a first interest. He can be introduced to

all the many styles and possibilities. I remember when I started

to

try to compose, I had to find out what’s going on and what was there

available to me. I asked how could I write if I wanted to?

Which

could I choose? Where can I go to find something to choose for a

way to write? Some of those things can be taught, but

certainly just above that beginning level we’re

talking about a coach; someone who can encourage, someone who can

perceive difficulties or who can sense directions that need to be

taken,

can guide listening, and frankly, help develop the technique. It

is necessary that the composer have technique. He can’t just sit

down and start rambling in some way. That can be taught, but

certainly it’s a matter of guiding. You’re teaching always

through

the music that the student is composing. So he has to do his

writing and then be criticized and helped with it. RL: This was commissioned by Guy

Fraser

Harrison in the Oklahoma City Symphony for Betty Johnson. It is

Elizabeth, but everybody knows her as Betty, the principal bassoonist

of the orchestra, a consummate artist. I think that I have not

heard a bassoonist that I enjoy more than I enjoy hearing her.

She

has retired from orchestra playing now but still is a wonderful

bassoonist. I sensed an opportunity to hear something performed

very well. At the same time, I had another work

commissioned, Symphonic Dialogues

for Violin, Oboe and Orchestra. This is one of those times when I

took on more than

I should have. The

symphony had given me deadlines on both of those works, and in December

I was looking at a March deadline for both works. They were

not moving very well, so I booked quickly an opportunity to go to the

McDowell Colony. It was in the winter, and it took me three

days to quit looking at the snow and the squirrels playing in it.

I composed the Bassoon Concerto

in three weeks, and the Symphonic

Dialogues in ten days.

RL: This was commissioned by Guy

Fraser

Harrison in the Oklahoma City Symphony for Betty Johnson. It is

Elizabeth, but everybody knows her as Betty, the principal bassoonist

of the orchestra, a consummate artist. I think that I have not

heard a bassoonist that I enjoy more than I enjoy hearing her.

She

has retired from orchestra playing now but still is a wonderful

bassoonist. I sensed an opportunity to hear something performed

very well. At the same time, I had another work

commissioned, Symphonic Dialogues

for Violin, Oboe and Orchestra. This is one of those times when I

took on more than

I should have. The

symphony had given me deadlines on both of those works, and in December

I was looking at a March deadline for both works. They were

not moving very well, so I booked quickly an opportunity to go to the

McDowell Colony. It was in the winter, and it took me three

days to quit looking at the snow and the squirrels playing in it.

I composed the Bassoon Concerto

in three weeks, and the Symphonic

Dialogues in ten days. RL: [Pauses for a moment]

I think so, only because I know that when it gets

off in the wrong direction, it changes. The history of

music is change, and change is inevitable. It’s not always good,

and sometimes it goes in directions we are not in great sympathy with,

but that evens out. I don’t know whether it will in my

lifetime or not, but I enjoy seeing where music goes, and I enjoy

seeing where my music goes. It’s for someone else to decide

whether that’s where it should have gone.

RL: [Pauses for a moment]

I think so, only because I know that when it gets

off in the wrong direction, it changes. The history of

music is change, and change is inevitable. It’s not always good,

and sometimes it goes in directions we are not in great sympathy with,

but that evens out. I don’t know whether it will in my

lifetime or not, but I enjoy seeing where music goes, and I enjoy

seeing where my music goes. It’s for someone else to decide

whether that’s where it should have gone.

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on July 15,

1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1996, and his recordings

were used on the air (without interview segments) several times both

before and after that date.

This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

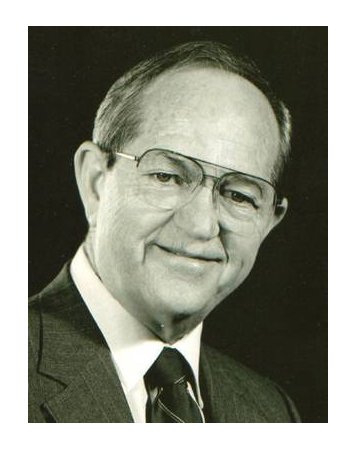

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.