A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: Beyond these

specifics of ensemble and location,

how do you decide which pieces you

will add or keep in your repertoire?

BD: Beyond these

specifics of ensemble and location,

how do you decide which pieces you

will add or keep in your repertoire?

BD: Is it good that

so many people now are blurring

lines between operas and musicals, and between serious music and

popular

music?

BD: Is it good that

so many people now are blurring

lines between operas and musicals, and between serious music and

popular

music? LM: I’m conducting

its second concert on December 16

in Rio de Janeiro. We have about thirty-five television stations

lined up, and we expect about a half a billion people to watch a

program. I’m giving a pre-concert concert in a park for — now

take a deep breath — three hundred and fifty thousand people!

It’s

a whole port which is roped off. It’s not the first concert I’ve

given there, but it’s the largest group that I’ve had to contend

with. My record so far is a hundred thousand, but three hundred

and fifty thousand is quite a

bit. I’m working a lot now for United Nations. They’re kind

enough to make me Goodwill Ambassador, with a little

passport and everything. I organized the Classic Aid Concert, which

you may have heard about. We gave that on September 30. We

had about

three hundred million people watching. It’ll be shown in the

States probably next October. I was very keen to organize this

concert for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees as a kind

of answer to Bob Geldof’s “We are the World.” My motto was, “We

are the World, too.” And in fact, Bob was extremely helpful to me

in organizing some of the exterior aspects of it. It was in

Geneva, and I invited some people from the theater and movie

world; Gina Lollabridgida, Catherine Deneuve, people like

that. Peter Ustinov was my co-host,

co-moderator, and we had about thirty-five of the world’s

greatest classical musicians. It was probably the most amazing

collection of violinists ever put on one stage — Itzhak Perlman, Gidon

Kremer, Anne-Sophie Mutter, and about everybody else in between.

And

we had Seiji Ozawa and Zubin Mehta, and Sir Georg Solti played the

piano.

LM: I’m conducting

its second concert on December 16

in Rio de Janeiro. We have about thirty-five television stations

lined up, and we expect about a half a billion people to watch a

program. I’m giving a pre-concert concert in a park for — now

take a deep breath — three hundred and fifty thousand people!

It’s

a whole port which is roped off. It’s not the first concert I’ve

given there, but it’s the largest group that I’ve had to contend

with. My record so far is a hundred thousand, but three hundred

and fifty thousand is quite a

bit. I’m working a lot now for United Nations. They’re kind

enough to make me Goodwill Ambassador, with a little

passport and everything. I organized the Classic Aid Concert, which

you may have heard about. We gave that on September 30. We

had about

three hundred million people watching. It’ll be shown in the

States probably next October. I was very keen to organize this

concert for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees as a kind

of answer to Bob Geldof’s “We are the World.” My motto was, “We

are the World, too.” And in fact, Bob was extremely helpful to me

in organizing some of the exterior aspects of it. It was in

Geneva, and I invited some people from the theater and movie

world; Gina Lollabridgida, Catherine Deneuve, people like

that. Peter Ustinov was my co-host,

co-moderator, and we had about thirty-five of the world’s

greatest classical musicians. It was probably the most amazing

collection of violinists ever put on one stage — Itzhak Perlman, Gidon

Kremer, Anne-Sophie Mutter, and about everybody else in between.

And

we had Seiji Ozawa and Zubin Mehta, and Sir Georg Solti played the

piano. LM: You

have a lot of people. The

technical level of conducting is much higher, but who is around who can

phrase like Bruno Walter or Furtwangler or Fritz Reiner? Who

has a fantasy of de Sabata? Even our best people would be

second-rate fifty years ago. Obviously I exclude myself, as each

one of my colleagues would, and I say that in jest, because what

else can one say? Your next question will be, “Do you consider

yourself to be a second-class musician?” The point I’m

making is that, staying away from the labels or the

comparisons or the evaluations, the music making is by and large

inferior because it’s so standardized and so set. People

are further and further away from the kind of breathing that music

making is really all about.

LM: You

have a lot of people. The

technical level of conducting is much higher, but who is around who can

phrase like Bruno Walter or Furtwangler or Fritz Reiner? Who

has a fantasy of de Sabata? Even our best people would be

second-rate fifty years ago. Obviously I exclude myself, as each

one of my colleagues would, and I say that in jest, because what

else can one say? Your next question will be, “Do you consider

yourself to be a second-class musician?” The point I’m

making is that, staying away from the labels or the

comparisons or the evaluations, the music making is by and large

inferior because it’s so standardized and so set. People

are further and further away from the kind of breathing that music

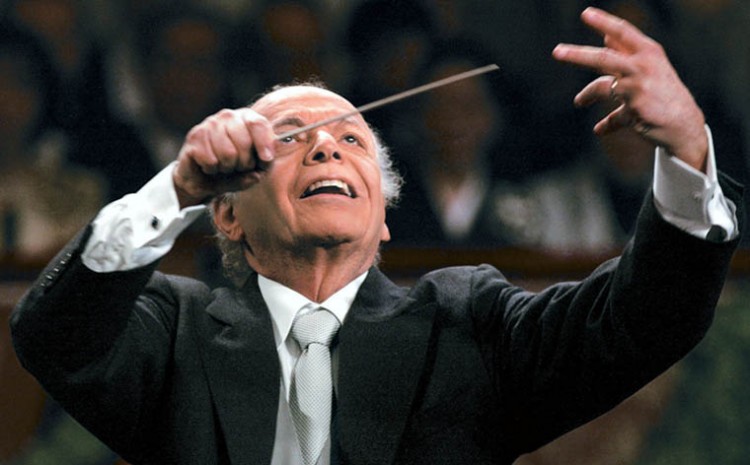

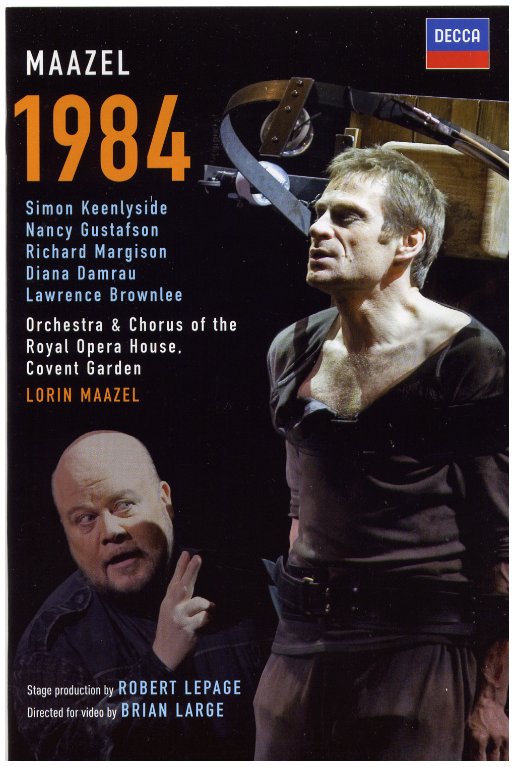

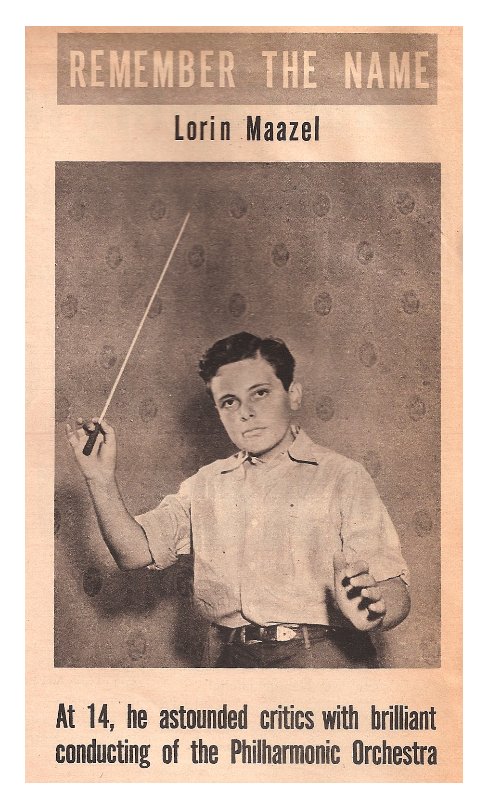

making is really all about.| For over five decades,

Lorin Maazel has been one of the world’s most esteemed and sought-after

conductors. In 2010-11, he is completing his fifth and final season as

the inaugural Music Director of the spectacular, Santiago

Calatrava-designed opera house in Valencia, Spain, the Palau de les

Arts "Reina Sofia." Music Director of the New York Philharmonic from

2002-2009, he assumes the same post with the Munich Philharmonic at the

start of the 2012-13 season. He is also the founder and Artistic

Director of new festival based his farm property in Virginia, the

Castleton Festival, launched to exceptional acclaim in 2009 and

expanding its activities nationally and internationally in 2011 and

beyond. Maestro Maazel’s 2010-11 season is highlighted by productions of Aida and his own opera 1984 at the Palau de les Arts; two concerts with the newly formed resident orchestra of China’s National Center for the Performing Arts in Beijing, a New Year’s Eve marathon concert of all nine Beethoven Symphonies in Tokyo, and return appearances with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He embarks on a Mahler cycle in London with the Philharmonia (for the Mahler centennial year of 2011) in additional to touring extensively with the orchestra in Europe. In September 2010, he marked the centennial of the premiere of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony at the Ruhr Festival conducting the work with forces numbering in excess of one thousand performers. In March 2011, he takes two Castleton Festival Opera productions to Berkeley, California (Cal Performances) for the West Coast debut of the company, with Britten’s Rape of Lucretia and Albert Herring. Maestro Maazel twice interrupted a brief sabbatical at the start of the 2009-10 season to step in for indisposed colleagues, first leading the Verdi Requiem to open the Verdi Festival in Parma, Italy, and then undertaking the second half of a Beethoven cycle in two weeks with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, including a Carnegie Hall concert. His season in Valencia includes three productions, Madama Butterfly, a double-bill of La vida breve and Cavalleria Rusticana, and La Traviata. He led two extensive tours in continuation of long-standing relationships with the Philharmonia Orchestra (giving concerts both in the UK and on a nine-city tour in Germany/Central Europe) and with the Vienna Philharmonic (encompassing performances in Berlin, London, Paris, Abu Dhabi, Cologne, Essen, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Lyon and Brussels, among other cities). In Vienna, he celebrated his 80th birthday with the Philharmonic, conducting the premiere of a Symphonic Suite drawn from his opera 1984, commissioned by the orchestra. He also made return appearances in the United States with both the National Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. In China, he inaugurated the new opera house in Guangzhou with a production of Turandot, and revived his Valencia Traviata to culminate the National Center for the Performing Arts, Beijing, Opera Festival. Maestro Maazel is a highly regarded composer, with a wide-ranging catalogue of works written primarily over the last dozen years. His first opera, 1984, based on George Orwell’s literary masterpiece, had its world premiere at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in May 2005, and was broadcast on radio and television by the BBC and on many other national radio networks worldwide. A high-definition video production of 1984, recorded at Covent Garden, was given a world premiere screening as one of the centerpiece events at the 2006 MIDEM Festival in Cannes, France (an occasion which prompted MIDEM to give a special award to Maestro Maazel for his lifetime achievements as conductor, composer and recording artist—only the 2nd such prize ever bestowed). A major revival of 1984 took place in May 2008 at the Teatro alla Scala (Milan) coinciding with the DVD release of the opera by Decca. Maestro Maazel’s compositional catalogue also includes a trilogy of concertos, Opp. 10, 11 and 12, “Music for Cello and Orchestra” (written for Mstislav Rostropovich) “Music for Flute and Orchestra” (written for James Galway) and “Music for Violin and Orchestra”; a symphonic movement (“Farewells,” Op. 14), premiered in 2000 by the Vienna Philharmonic, which commissioned the work; and several contributions to repertoire of narrated texts with orchestra, including two children’s stories, “The Giving Tree” and “The Empty Pot.” He enjoys orchestrating violin and piano works of 19th and 20th century masters, and created 17 Italian-song arrangements for violin, tenor and orchestra for a best-selling recording with Andrea Bocelli and the London Symphony Orchestra (for which Maestro Maazel was conductor and violin soloist). His symphonic synthesis of Wagner’s Ring cycle (“The Ring without Words”) has been performed by many of the world’s leading orchestras. A second-generation American born in Paris, Lorin Maazel began violin lessons at age five, and conducting lessons at age seven. He studied with Vladimir Bakaleinikoff, and appeared publicly for the first time at age eight, conducting a university orchestra. Between ages nine and fifteen, he made his New York debut at the 1939 World’s Fair, conducting the Interlochen Orchestra; led the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl, sharing a program with Leopold Stokowski; and conducted most of the major American orchestras, including the NBC Symphony at the invitation of Toscanini. His New York Philharmonic debut came in 1942. He was only twelve years old. At 17, he entered the University of Pittsburgh to study languages, mathematics and philosophy. While a student, he was a violinist with the Pittsburgh Symphony, where he also served as apprentice conductor during the 1949–50 season, and organized the Fine Arts Quartet of Pittsburgh. In 1951 he went to Italy on a Fulbright Fellowship to further his studies, and two years later made his European conducting debut, stepping in for an ailing conductor at the Massimo Bellini Theatre in Catania, Italy. He quickly established himself as a major artist, appearing at Bayreuth in 1960 (the first American to do so), with the Boston Symphony in 1961, and at the Salzburg Festival in 1963. In the years since, Maestro Maazel has conducted more than one hundred and fifty orchestras in no fewer than five thousand opera and concert performances. He has made over three hundred recordings, including symphonic cycles/complete orchestral works of Beethoven, Brahms, Debussy, Mahler, Schubert, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Richard Strauss, winning 10 Grands Prix du Disques. His discography includes a range of violin recordings, often in a double role as soloist and conductor, from virtuoso showpieces to Mozart Concertos to Stravinsky’s “Soldier’s Tale.” He is the recipient of two ASCAP awards for contributions to American music and has made appearances in every major music center and at every prominent festival internationally. He has conducted numerous world premieres by both established and up-and-coming composers and performed hundreds of concerts as a violin soloist, including appearances with such orchestras as the Vienna Philharmonic, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Philharmonia and the New York Philharmonic, among many others. Maestro Maazel has been music director of the Symphony Orchestra of the Bavarian Radio (1993 until summer 2002), music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony (1988–96); general manager and chief conductor of the Vienna State Opera (1982–84) — the first American to hold that position; music director of The Cleveland Orchestra (1972–82); and artistic director and chief conductor of the Deutsche Oper Berlin (1965–71). He was named Honorary Member of the Israel Philharmonic in 1985 when he conducted its 40th Anniversary concert. He is also an Honorary Member of the Vienna Philharmonic, and is the recipient of the Hans von Bülow Silver Medal from the Berlin Philharmonic. His close association with the Vienna Philharmonic includes 11 internationally televised New Year’s Concerts from Vienna (often with Maestro Maazel making an added contribution to the festivities as violinist). Alongside his prodigious performing activity, Maestro Maazel has found time to work with and nurture young artists, based on his strong belief in the value of sharing his experience with the next generation(s) of musicians. He founded a major competition for young conductors in 2000, culminating in a final round Carnegie Hall two years later, and has since been an active mentor to many of the finalists (and instrumental in launching their international careers). He has an equally strong commitment to environmental and humanitarian causes. He has raised millions of dollars on over fifty occasions for the benefit of such entities as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), World Wide Fund for Nature, the Red Cross and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Maestro Maazel speaks French, German and Italian fluently (and has a working knowledge of Portuguese, Russian and Spanish). Among his honors, decorations, and awards are the Commander’s Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Legion of Honor of France (Chevalier), the Knight Grand Cross from the Republic of Italy, and the Commander of the Lion of Finland. He also has been awarded the title of Goodwill Ambassador by the United Nations. An avid reader, classic film buff, and theatergoer, he also enjoys playing tennis, swimming and collecting American paintings and Oriental art. -- From Maestro Maazel, the official website

|

This interview was recorded at Orchestra Hall in Chicago

on October 22, 1986. Portions were used (along

with recordings) on WNIB later that year and again in 1990, 1993, 1995

and 2000. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award-winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.