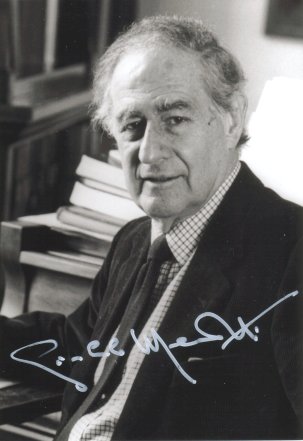

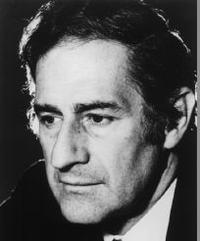

Composer Gian Carlo Menotti

Three Conversations with

Bruce

Duffie

Composer Gian Carlo Menotti

Three Conversations with

Bruce

Duffie

Most of the interviews I have done over the years have been singular events. A few of my guests, however, have been willing and available to return to my microphone. Gian Carlo Menotti was gracious enough to speak with me on three occasions, and all of those conversations are presented here in the original sequence.

The first of the three meetings took place on March 19, 1981, when

Menotti

was in Chicago to oversee, and (as we found out at the curtain calls

when

he removed his costume/disguise), to participate in a production of The

Egg as given by the William Ferris Chorale at St. James Cathedral.

Even though this meeting was to promote the performances, I had the

foresight

to ask not only about the specific event, but also to probe his mind

about

things related to other works and music in general. I was also

contributing

at the time to Wagner News, the publication of the Wagner

Society

of America, so Menotti's production of Tristan und Isolde was

of

interest, hence my inquiry into that unlikely topic.

Bruce Duffie. Would you tell us a little bit about The Egg?

Gian Carlo Menotti. I’m not going to tell you anything about The Egg because I feel that the audience should come and find out for themselves what it’s all about. What I can tell you, it was written for a cathedral, for the Washington Cathedral, and it is aimed at Easter, although it can be done at any time. That’s why we have the egg. But what the egg symbolizes and why it is called The Egg and what it’s all about, that you have to go and find out for yourself.

BD. Is there any relationship between the kind of work The Egg is and the Canticles that Benjamin Britten wrote?

GCM. No. It’s a completely different kind of work.

BD. You have composed a great many operas which are done all over the world. Would you tell us a little bit about your feelings of the role of the composer in contemporary life, or the composer specifically for opera?

GCM. You asked me a very difficult question. I feel that the composer has always been - I shouldn’t even say the composer; I think the artist in general, especially in America - has been always on the margin of society. We are supposed to entertain people rather than really be part of their daily life.

BD. Is it the public that feels you are supposed to entertain us?

GCM. I’m afraid so. You always say, “What are we going to do this evening?” Generally art comes after dinner when you’ve had a few cocktails and you’ve had your dinner, then you go to the theater or you go to the opera or you go to see a painting show because then you’re also going to get a cocktail at that time. You go to an opening and you look at the other ladies. It is always sort of a social function. In a certain way, I would say that we are the after-dinner mint of society rather than being the bread of society. Actually, I think it is very important that people, even business people, should realize that, first of all, they use us all the time, from morning until night. They get up in the morning, they go to take a shower and they whistle a tune, and who wrote that tune? A composer. They choose a necktie. Who designed that necktie? Somebody who studied even minor art. I mean, it’s not art, but still it is somebody who studied art. They go into their very modern office which was designed by an architect who has seen the paintings of Mondrian, certainly, and so on. And his wife has to choose a dress, and who has designed the dress? It is an artist, whose pencil they used. Practically everything that we touch or use in modern life has some connection with art. And I think that is very important that people should realize how much they need art in their life.

BD. We take it too much for granted, then.

GCM.

Yes, and people don’t even know that they are using something that has

been designed by the artist, that actually they are in the hands of

artists.

Their club, their silverware, the place they are eating from.

Even

if they are commercial artists, still they are designed by

artists.

But more than that, I feel that the serious artist, himself, has to

find

a more creative place in modern society. That’s why I founded my

festival in Spoleto in Italy. As I said, I want to be the bread

of

the community. I want to be part of the community. So I

looked

for a small town that was on the verge of bankruptcy, a very poor

town.

It just happened to have two gorgeous theaters. I went there and

I tried to help this town with my music and with the help of my fellow

artists. It is quite touching to see how artists who come to

Spoleto

feel the dignity of being necessary to the life of the town. It’s

marvelous to feel wanted.

GCM.

Yes, and people don’t even know that they are using something that has

been designed by the artist, that actually they are in the hands of

artists.

Their club, their silverware, the place they are eating from.

Even

if they are commercial artists, still they are designed by

artists.

But more than that, I feel that the serious artist, himself, has to

find

a more creative place in modern society. That’s why I founded my

festival in Spoleto in Italy. As I said, I want to be the bread

of

the community. I want to be part of the community. So I

looked

for a small town that was on the verge of bankruptcy, a very poor

town.

It just happened to have two gorgeous theaters. I went there and

I tried to help this town with my music and with the help of my fellow

artists. It is quite touching to see how artists who come to

Spoleto

feel the dignity of being necessary to the life of the town. It’s

marvelous to feel wanted.

BD. And then the people who come to Spoleto come for the festival, and that is their bread, as you say.

GCM. And they bring the bread to the city. For me, that is what I enjoy most, when I feel that I’m needed and I’m not only there. If you really think about the audiences you get at the Metropolitan or at Salzburg or at Covent Garden, they’re all the same old faces. They change dresses or they change the speech, but it’s a very small part of the world. That’s why when people talk about opera, opera for me is not only what it given at the Metropolitan but what is given in the school, in colleges, in hospitals. Wherever an action is sung, that is opera, and that’s why I love to do something like The Egg, because that is done in a church. Still it is an opera.

BD. Many of the things that you have written are on a little smaller scale and can travel around to different kinds of communities, different kinds of theaters, and in many cases can be done by amateurs very well.

GCM. Yes. I must say that perhaps the most moving performance I heard of Amahl and the Night Visitors was in a hospital for children, in a ward where there were children, and it was so moving to see. It was also performed by a troupe of amateurs, but I cried all through it.

BD. It was a very moving time because of where it was and why it was.

GCM. Of course.

BD. So, then, you feel that everything that interacts with people in their daily lives should interact with their reaction to the arts.

GCM. Of course. I’ve maintained that for a long time. For me, art must be an act of love. It cannot be just masturbation. It has to have something to give. It must speak to somebody. It’s very interesting that most artists feel that need of communicating with somebody. I feel that art for its own sake is an illusion. There’s a marvelous essay by Jean-Paul Sartre on literature or art in general, in which he maintains that for a work of art to really exist, it must have the creative cooperation of the person who receives it. A book doesn’t exist unless it is read, and it only exists in relation to the person who is reading it. The same thing with music: Music only exists in not only my ear, but I need your ear to make it work. So actually the audience also is part of the work of art.

BD. How does this jibe, then, in the electronic age, where we have disks that produce sound and tapes that produce video. Is this going to change opera in such a way that we can now dictate when we watch and listen to the opera? And is this a good step for the opera, then, rather than going after a long, hard day at the office?

GCM. It is perhaps too early to tell. I find it extraordinary that all this radio and all this canned music hasn’t killed music yet, which really shows how strong and how indestructible great art can be. I was a bit horrified at the beginning, when you get in an elevator and all of a sudden to hear a Mozart string quartet while I was going up to the thirteenth floor. But it is marvelous how, in a certain way, it doesn’t really destroy the essence of music. You still want to hear a string quartet played by people and not only by the shadows that come out of a can.

BD. As a composer, do you feel any more satisfaction knowing that when someone takes a disk off of his shelf and plays it, he may probably have more concentration and more being in tune with this performance than if he just was dragged to the opera that night?

GCM. Yes, perhaps, but only for a while, because music cannot be frozen. As a matter of fact, I find it very harmful that people listen to recordings too much, and then they feel that is the only way that the work exists. Then they’re going to hear another performance and say: “Oh, that’s wrong. That’s not the way I like this symphony,” because they’re using the same record and hearing the same work always the same way with the same tempo. Actually, the music lives in time, and time changes. One day, one piece of music has to play maybe a little faster than another time; it all depends. I’ve seen this with my own operas. It depends from the concentration, from the audience. For example, in The Medium, when I very much insist on certain very long silences, and then my singer asks me: “Well, Mr. Menotti, how long should the silence be?” I say, “Why, you must feel it. Monday can be this long, and Tuesday you might it cut it in half.” Tempo is the same thing. What is the tempo? You must feel the tempo. As a matter of fact, Toscanini told me a very interesting story. When he first performed Verdi’s Requiem, there was a passage in it where he felt that he needed to go slowly, to make a ritardando, but there was nothing in the music, so he asked to play it for Verdi. It’s one of the few times that he actually met the maestro, himself. So he played it on the piano, and when he got to this point he just made a ritardando, and Verdi didn’t say anything. Then he stopped, and he said: “Maestro, is it all right?” And Verdi said, “Of course. Yes, it’s fine.” He continued, “But I made a big ritardando,” and Verdi replied, “Yes, of course.” “But you didn’t write it in the music,” continued Toscanini. So Verdi said, “Well, you will be a very poor conductor if you didn’t feel the ritardando yourself, without my having written it.”

BD. So, then, you as a composer expect everyone to make his own impression and his own direction.

GCM. They have to breathe with the music. Some people breathe a bit faster than others. It all depends what kind of a heart you have.

BD. And the same people will breathe differently at different times.

GCM. Of course.

BD. So the reaction, then, to a recording made twenty or thirty years ago will be different today than when that recording first came out.

GCM. Yes. Some of the famous records now sound pretty silly to us. But we’re in another age and our hearts perhaps beat in a slightly different way.

* * * * *

BD. Let me ask you about translations. As an opera composer, are you in favor of translating the opera into the language of the audience?

GCM. You ask me very difficult questions. That is a very difficult question to answer, indeed. I feel that contemporary opera should be translated. As a matter of fact, we know from the records of Puccini, of Strauss, they all wanted to have their works translated because, after all, a composer works so hard in commenting with his music the meaning of a certain phrase, and all of a sudden, if instead of saying: “Io t'amo,” or “I love you,” and you say, “Chuki baki buki,” what is the poor audience going to think? I do think that for certain operas, like Traviata perhaps, or Norma, everybody knows the story, and they should know the libretto by now. Perhaps the translation is not necessary. But if you have an audience that is educated in opera—for example, in Italy we used to have French operas in Italian. Now they begin to give them in French because most Italians can understand French well enough to follow the story. But I feel that for a new work and even for certain works, I think that you must understand what is going on. I’m sure that some people that are purists will shudder, but I think that Pelléas and Mélisande is a work that unless you really understand every phrase of it, becomes a bore. It is a wonderful opera. It’s one of perhaps my favorite operas in the world.

BD. You have staged this work, yes?

GCM. Yes, yes, and with great love. But I feel that to be able to enjoy it, you must understand what people are saying, because Debussy really feels every phrase. It’s a recitative from beginning till the end, so unless people know what you’re telling, you are lost.

BD. More than just having read the libretto beforehand?

GCM.

No, you really have to understand the words right then and there.

You cannot try to remember, “What did he say then?” You must know

what they are saying at the very minute.

GCM.

No, you really have to understand the words right then and there.

You cannot try to remember, “What did he say then?” You must know

what they are saying at the very minute.

BD. Do you think the running translations that we see on the television now help a lot?

GCM. I’ve never seen an opera with those. I must tell you that, although I am here right in front of those microphones, I hate radio and I hate television. [Laughter] I don’t have a television in my house. [Laughter.]

BD. You prefer, then, the live music rather than the canned music.

GCM. Yes, I like people with blood and bones. I don’t like shadows so much. But I do feel that television is an inevitable evil, and certainly it is the most popular form of theater today.

BD. Do you think that we misuse it?

GCM. Yes, of course it is misused. We all know that. [Laughter] I don’t have to tell you that, but one must accept popular theater. I have written the very first opera ever written for television, Amahl and the Night Visitors, and the very first opera written for radio, The Old Maid and the Thief.

BD. Now here’s a good case in point. You write an opera for radio, for one particular medium, and then it becomes staged. When you wrote it, did you have in mind that it could be used in many ways, or do you write just for the one particular situation?

GCM. When I wrote Amahl, I cheated. I knew that I would want to see it on the stage, so I wrote a television opera that could be easily staged. But there is another opera that I wrote specially for the cinematic media, which never became popular, The Labyrinth. That one could never be done on a stage; it is really only for television or movies. Unfortunately, it has not been picked up, but I hope that one day somebody will revive it because I think it is an interesting example of how opera can be done for the cinema.

BD. Would it be possible to get you into the studio, working with the electronics to make a purchasable videocassette of this opera?

GCM. Oh, yes, of course. [Laughter] Are you going to ask me?

BD. I wish I had the money to produce it. It’s interesting to see what composers think of their own works. How do your works fit into the flow of opera from the early 1600s to the present and beyond?

GCM. I think it is a very great mistake for any artist to be self-conscious about their position in the history of music. I hate musicologists, and I let them decide what I am. They have placed me here and there, they kicked me out from one thing to the other, and they have given me all sorts of extraordinary labels, most of them wrong, as far as I’m concerned. But that’s their job. My job is simply to write music. They say I’m very eclectic, but I feel that the artist is like a human being. We all have a father and a mother. I don’t believe that an artist is born out of nowhere. We have a tradition behind us and I accept my family. I have a family behind me of great masters, and I accept the education I received from them and I try to add my own voice.

BD. Are we confusing the artist with something that the artist has created?

GCM. I don’t quite understand what you mean by that.

BD. Are we losing the thread? When you say that the music historian puts the artist in one place or another, are we looking at the artist as a piece of steel sculpture rather than as a flesh-and-blood human being?

GCM. Yes, well, indeed. As a matter of fact, The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore is a symbolical work about the life of the artist. The unicorn is his youth, the gorgon is middle age, and the manticore is the old age. The poet has these three monsters, and every time he’s sick of all this, he goes from one period to the other. First he kills the unicorn, or he tells people he has killed the unicorn. Then he kills the gorgon, then the manticore. Everybody follows; whoever has copied him and gotten unicorns and gorgons and manticores, they kill their manticores and gorgons and unicorns. But when the poet is dying at the end, they go to his house and find that he still has all three of them. For the artist, any work he does is part of his own development, and when people ask me, “What is your favorite work?” I don’t know. They all represent some joy, some pains.

BD. Are they your children?

GCM. They’re all my children, and they all mean something. Some have been luckier than others, but it is difficult for an artist to say: “This is my most important work.” They are all part of our lives.

BD. Are some of them are more important at different times?

GCM. At different times, and they all represent a part of our development.

BD. You mentioned that the critics have put you in one place or another, but one place that Gian Carlo Menotti always is is in the hearts of the public. Thank you for everything you have given us.

GCM. Well, how very nice. Thank you! That’s the nicest compliment.

* * * * *

BD. You have staged Tristan und Isolde. Where do you feel that Wagner falls into the place of being viewed in modern society? Is he simply too overblown for this age?

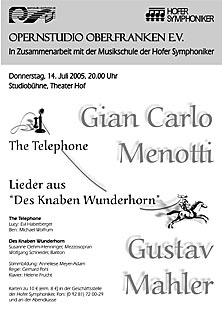

GCM. It’s very difficult even to answer a question like that. Look at Mahler. Whoever thought that Mahler would become so popular with the young people? If you talk about overblown music, certainly some of Mahler’s symphonies are just overblown Tchaikovsky. All of a sudden the young people all over the world have discovered Mahler, and now they accept it, and there couldn’t be more sentimental and emotional music than Mahler’s. I always feel that Wagner is just like electricity; you may like or not like electricity, but you’ve got to use it! He has revolutionized so much in music. I think that perhaps what one thinks is overblown in Wagner is the fact that he was a victim of his own librettos. He took himself so seriously as a writer that he was unable to cut his librettos to size. To use every word he wrote, he just trashed his music. It becomes very repetitious. But, my God, there are so many divine moments! If you just take the beginning of Lohengrin, what is just a plain chord, that everybody’s heard before, but still, the way he has orchestrated it with the divided strings, it’s just a new sound. It was a new sound for everybody. There are wonderful, magic moments. Or the horn call at the end of Meistersinger after the big fight. They are just magic moments.

BD. How did you approach the Tristan?

GCM. I don’t try to be avant-garde in my stagings; I try just to do what I thought the composer would want. And if you do that, if you really look over the librettos very carefully, you’ll find out that there are so many things that people never do. Without really trying to be shocking or anything, I found things in Tristan that of course shocked everybody. For example, in the second act, Isolde comes out in kind of a very transparent gown, and she was naked under it. I said “You must come out just with that,” and she gasped, “Oh, Mr. Menotti!” She was a very beautiful girl, and I did that not because I wanted to shock but simply because at the end of the love duet with Tristan, when King Marke comes in, Wagner puts in the staging that Tristan runs over to Isolde and covers her with his cloak. So it means that she must have had something to hide! [Laughter] There are little things like that. Even in old familiar Bohème, there are so many things people never do, amusing touches. For example, in the last act, when the boys are all together and they are about to start to eat this meager little thing, one of them gets up and they say, “Where are you going?” and he says, “I’m going to visit the king.” Well, what do you think it is? He’s going to the bathroom. He even makes a joke about the newspaper he is going to look at because, at that time, in the bathrooms they had pieces of newspaper, you know. There are very funny touches like that. Most any libretto has them. They always make Don Pasquale into such a silly opera, and it is such a marvelous work. It was, perhaps, the first realistic opera buffa opera ever written. It has to be done in that spirit, the tragedy of an old man who falls in love with a young girl. The old man should not be made ridiculous. It’s a sad story, in a certain way. Actually, the evil people in the opera are Norina and her lover. They take advantage of this poor old man.

BD. Let me ask about Bohème. Would it be wrong for a designer to include in the first and fourth act garret a little room off to the side with a sign on it that says “Washroom” or “Men” or something like that? Would that be out of place?

GCM. No. At that time they would not have a sign. But when I did it in Paris, I just had sort of a screen, and he took a pail of water and went behind the screen and went to this little door. I remember, when Liebermann was rehearsing, he said, “Gian Carlo, what are you doing?” I replied, “Well, read the libretto." It did not cause any scandal, but there are many charming touches. I had great fun especially with Don Pasquale. I find so many things in that opera. People feel so near this old man.

BD. That’s the thing, to make the audience identify with him. Would there be any point in changing it around a little bit so that the old man does get the girl? Maybe have Ernesto get his by a motorcycle or something?

GCM. [Laughter] I think it’s better for the old man the way it is. It’s a happier ending if he doesn’t get the girl.

* * * * *

BD. Is art like this cyclical? Does it come for a few years and then go dormant and then come back?

GCM. Of course it changes. We were talking about Mahler. Twenty years ago, nobody could even mention the name of Mahler. He was never played anywhere. At that time, it was Sibelius. Everyone was playing Sibelius.

BD. And all of a sudden Bruno Walter does some Mahler symphonies.

GCM.

And then Walter starts with Mahler, and now it’s Mahler. Mahler,

I’m afraid, will also go down. It’s a fluctuating thing.

Something

remains at the end.

GCM.

And then Walter starts with Mahler, and now it’s Mahler. Mahler,

I’m afraid, will also go down. It’s a fluctuating thing.

Something

remains at the end.

BD. Are you conscious of this when you’re writing?

GCM. No, I don’t think about that. I had my period when I was supposed to be a great genius of opera, and now everybody spits at me. I’m sure that after I die, I hope the way will come up again. [Laughter] Everybody always says, “Why do you have so many critics against you?” But I feel that in a certain way it is almost as if God gives you a challenge. I think that a good work of art must be stronger than any bad criticism. If it doesn’t survive bad criticism - for that matter, if it doesn’t survive good criticism - it’s a weak work. I’m very proud that my operas are all still alive in spite of all the insults they got. They go on and that’s important for me. The fact is that The Medium and The Consul are done all over the world, and that’s important. I feel in a certain way it’s almost as if it is a challenge. All right, you have a point of view. Now let’s see whether the opera will fall under the blow. And if they don’t fall, then I know they’re in good health.

BD. Is there a place in the modern repertoire for works by really unknown composers or lesser-known composers?

GCM. There should be. In chamber music, I think that the contemporary artist is doing pretty well. In opera, alas, I think that the contemporary repertory is very limited; there are very few. If I may say that very modestly, except for Benjamin Britten and me, who else is there that can really hold? There are a few like Von Einem’s, but they get one or two performances and then they are just like paper napkins. They are used and they are more or less thrown away.

BD. Have you seen the works of Thomas Pasatieri?

GCM. Yes, but I don’t know much of his music. I must say I was disappointed about his last work, the one-act that he did at the New York City Opera. I thought it was rather weak. I told him, as a matter of fact.

BD. Has he written larger works?

GCM. There are some. He sent me the tape of one and I’m going to listen to it, but I really don’t know it. I know some of my own pupils - Lee Hoiby, for example. He’s almost good, but he doesn’t yet have the dramatic force in his work to become an international composer. You must be able to speak not only to your local audience, you’ve got to be able to travel over the world with music nowadays. Believe me, I think we need more names in the modern repertory because so many contemporary operas are so boring, and they get the audience so bored that now, even if you put any contemporary opera in any city, everybody goes: “Ahhh! [in a tone of disgust] Who is going to want to go?” Well, that’s bad for us, for anybody.

BD. It’s given opera a bad name.

GCM. A bad name. Really, a bad name. The people say, “Well I’ve heard Cavalleria, I’ve heard Tosca, I’ve heard this one and that one, so then they don’t go because they’ve heard it so many times. And they don’t go to the new one because they’re afraid of being bored.

BD. Is the answer to revive the unknown operas of the last century?

BM. We need also new operas.

BD. Is it the responsibility of the composer to make it accessible, or is it the responsibility of the audience to go and access themselves, really?

GCM. No, I think the composer must make clear what he’s saying. Even Mozart made quite a distinction between the start of his string quartets to his operatic style. The most clear melodies are all in his operas. You have to make your point then and there. You cannot wait until the curtain is down and the people go home and they say, “Ah! That’s what you wanted to mean." You must. You’re speaking. It is a conversation. It is a very direct conversation. It’s not like a string quartet that you can think about it. People are saying something to you then, and the emotion must be made then and there. I think that it is important for any artist to express himself as clearly as possible. I don’t mean easily or just to say stupid things...

BD. But it must be clear.

GCM. Yes, clear. Even Marcel Proust says rather complicated things, but he says it in a very precise and a very elegant way. Sometimes you read cheap novels that you don’t quite understand what it’s all about. There’s an awful lot of bromides which are said in a very complicated way, and it means nothing. But an artist has to be clear. That’s why I adore Schubert. Most of all, I love his absolute clarity. He says what he has to say in a harmonic scheme that’s almost childish sometimes. It’s nothing but tonic dominant, tonic dominant. Then he puts a little dissonance, and it becomes so dramatic that you go: “[Sharp intake of breath]” You sit up, like that. That’s a wonderful thing. Very often when I hear some modern music, I think about the old saying that they burn down a whole house just to fry themselves two eggs. Sometimes you need a very complicated setup if you have something very complicated to say, but it must be a necessity and not part of a style.

BD. Are too many composers writing for the edification of other musicians?

GCM. Yes, I think that so much music today is just written for other musicians. When people talk about writing for the public, I’m not writing for them. They’re writing for the public, but their public is the other composers, the critics, the musicologists, and that’s their public. They are writing really for that public, not for themselves. I’ve spoken to so many composers and say, “Is that really the music you want to write?” They say, “Well, Mr. Menotti, my teacher said that I have to be more modern.” I say, “Oh, my God.”

BD. You write the music you want to write.

GCM. You have to. You have to. More than that, it is the only music I’m capable of writing, which is the important thing. We all have our own limitations.

BD. It’s given so much pleasure. This is the thing. I read the critics, of course, and see them malign you occasionally...

GCM. Oh, more than occasionally.

BD. I appreciate your taking the time today. Thank you so very much.

GCM. It was great fun talking to you.

=== === ===

-- -- --

=== === ===

Now we jump ahead about twelve and a half years to October 28, 1993.

BD. We will chat a little bit about all kinds of things. Do you like being a wandering minstrel?

GCM. No, at my age I’ve learned now to be a pater familia for many years. I love my home in Scotland. I love to be there with my son and my two grandchildren and of course my daughter-in-law. I have a very quiet and happy life there. Life in Scotland is life the way it used to be fifty years ago, and that’s the way I like it. [Laughter] [For more about Menotti's life in Scotland, see the article at the end of these interviews.]

BD. Is there any correlation, then, because you write operas the way you wrote operas fifty years ago?

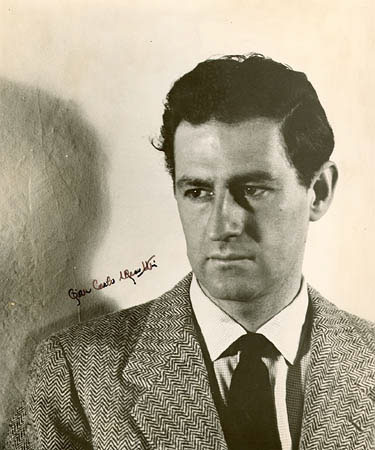

[Time Magazine, May 1, 1950]

GCM. I write operas the way I wrote them fifty years ago simply because I think an artist writes always the same kind of opera. I’m eighty-two, so fifty years ago I was thirty, and at that time I wrote I wrote The Medium, The Consul. I think that in a certain way, an artist always writes the same opera, the same book, paints the same picture. Of course, it develops, but it’s always you. It mirrors your soul and your being, so you just don’t have to change. Of course I write the same way because I’m the same man that I was fifty years ago.

BD. But I would hope there would be quite a bit of progression and development, too.

GCM. I don’t think that art progresses or develops. That’s one of these horrible things people say about progressive art, and there really is not such a thing. Art is not something that is a commodity that gets better as it goes on. Its value is always the same. Pre-Columbian culture is just as good in its way as a Michelangelo statue or as a Henry Moore statue. You aren’t going to say that Henry Moore is better than Michelangelo; it’s just different. Henry Moore is Henry Moore, and Michelangelo is Michelangelo, but one is not better than the other simply because it’s nearer to us.

BD. So, then, you are different from any other composer.

GCM. Well, of course.

BD. But are your works different at all in amongst your oeuvre?

GCM. Well, of course, because we change as we get older, and sometimes when I hear the works that I composed when I was in my twenties and my thirties, I say, “Oh, look, how strange! Did I really do that?” [Laughter] But then, of course, I find it’s just the same when suddenly you remember things about your childhood, about your youth that you have forgotten, and you wonder how did that happen? How did I ever fall in love with that person? Or why did I act like that? But still it’s part of yourself always.

BD. Do you, as the composer and usually the librettist, too, fall in love with your characters?

GCM. You have to actually, because especially in the theater, the only way you really can create a character is that you have to live their life, and you have to find yourself on the stage with them, in a certain way. So yes, I do. And generally, if I write a comic opera and I don’t find myself smiling and laughing, I know it’s not a good scene, it’s not a good opera, or I will not create the character. It's the same when I write a tragedy, if I’m not moved, myself. I think that that happens with every artist. I remember when Tennessee Williams came to Spoleto to see one of his plays... He wrote two plays for us in Spoleto; one was The Night of the Iguana, which was the world premiere, and the other one was The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore. I was sitting in the box with him, and I was very amused to see how he would laugh at the funny lines as if he’d never heard them before. [Laughter] It was charming. That is the way, actually, sometimes I feel when I hear my music. I get moved by it because I live within the character. As a matter of fact, that reminds me of a charming story that Toscanini told me about Puccini. One evening Toscanini called up Puccini and asked him for dinner, and Puccini said, “I can’t because I have to go and hear Bohème.” That was in Milan, and Toscanini said, “Bohème? We’re not doing Bohème at La Scala tonight.” “No, no, no, I’m going to Teatro dal Verme,” which was a second-rate theater. And Toscanini said, “You’re not going to hear Bohème there, for God’s sake! What a horrible orchestra. There are more clarinets than violins, and they’re second-rate singers. How can you bear it? Forget it! Just come and have dinner.” Puccini said, “No, I promised. I have to go there. They’re expecting me.” So Toscanini said, “All right, let’s go late, just for one act, and then we’ll go and have dinner.” And Puccini said, “All right, as long as I go, but I must go there.” So they went there for the third act, and Toscanini said, “It was a terrible performance,” and he was so embarrassed, and all of a sudden he looked at Puccini, and Puccini was crying. And so at the end of the act, Toscanini turned to him and said, “I can’t believe it! You have heard me conduct Bohème. I give you a marvelous performance of it at La Scala and I never saw you so touched. And here, you come to hear this horrible performance, and I see you this way.” And Puccini said, “Well, you give me perfection, and they give me their heart.” It’s wonderful that Toscanini, himself, told this story on himself. But I think that Puccini probably was touched by that. I’m sure that every time he heard Bohème, he also got touched by his own music.

BD. I assume, then, that you are touched by your own music, even if it’s thirty, forty, fifty, sixty years old.

GCM.

I do, but I rarely listen to my old works because they make me very

nervous.

I always think I could do better or should have done better, so I only

listen to them when I have to. [Laughter]

GCM.

I do, but I rarely listen to my old works because they make me very

nervous.

I always think I could do better or should have done better, so I only

listen to them when I have to. [Laughter]

BD. But does it give you a sense of satisfaction to know that some of these old works are performed over and over again, all over the world?

GCM. Well, of course. It is nice to have the works done, to have the works remembered. It is nice that almost everywhere I go, somebody says: “Oh, I remember this performance or that performance of your work.” Even tonight, the boy who came to meet me at the airport started singing a phrase from one of my very little-known operas, The Most Important Man, and he still remembered all the words, even in the Italian translation. [Laughter]

BD. Then I’ll tell you that I remember the Tamu-Tamu that was here. Along with many of the others, of course, but that’s a lesser-known work.

GCM. It was not very well received here.

BD. Well, I enjoyed it.

GCM. I thank you. I’m fond of that work, and I'd like to bring it back. It was a big success in Italy. It went very well, and I don’t know why it was received with such hostility here.

BD. Is there any way that a composer can predict the reaction of the public?

GCM. No, never. No, never, never. You cannot tell it from the general rehearsal. Of course, the theater is a very mysterious animal. You never know how it’s going to act in front when the audience is there. It’s just like a stubborn child when you ask him, “Please say hello to Daddy” or something. They’re, “[Makes growling sound.].”

BD. [Laughter]

GCM. And the same thing with a play. It seems to go very well in rehearsals; everybody laughs, it’s a wonderful success, and then in front of the audience it becomes another play. That explains why great playwrights like George Bernard Shaw, after having written such brilliant plays, all of a sudden he could write something absolutely which was so untheatrical you wonder how is it possible? Even Tennessee Williams, to go back to him. It's the same thing with an opera composer. If you think of Bizet, who wrote such a wonderful operas like Carmen and Les Pêcheurs de Perles, also wrote Ivan IV, which is nothing to be remembered forever. It’s hard to believe it’s the same composer. [Laughter] So you really never know how an audience is going to react. As a matter of fact, I’ll give you an example of how unpredictable theater can be. I always like to remember the premiere of The Consul in Paris. It was my debut in Paris. No, actually, I had already done The Medium. But anyway, the concert was quite a premiere. Tout Paris was there, and all the composers and all the musicians and the artists, and we were doing it in English, which was also very dangerous. People had heard it had been a success in New York, and they were all ready to kill it, if they could. [Laughter] So I put in the program, “No applause between acts.” But it was a marvelous performance, with that wonderful Magda, Patricia Neway. I felt that there was a tremendous electricity in the audience, but I couldn’t tell because at the end of the first act there was no applause, so I was a little bit nervous. Thomas Schippers was conducting, and it was a brilliant, but the audience was very silent. Then at the end, we got to the last chord after she dies, taking gas, and the last chord, and the curtain was to come down, and no curtain. Schippers holds the brasses as long as he can until they’re all blue in the face, and then finally had to stop. Silence. Still no curtain. I was standing at the back of the main floor, so I ran backstage, and I said, “Rideau, rideau!” They said, “The man with the curtain has gone to have a beer.” I said, “Oh, my God! Well, let me...” Can you imagine how long that silence was, with poor Patricia Neway dead and just kind of saying, whispering as loud as she could, “Curtain! Curtain!” So finally they showed me a button, and I said I didn’t care about the unions. I was not supposed to, but I rang down the curtain. Then, of course, we thought, well, the whole performance has been destroyed. Patricia Neway was hysterical, and everybody was saying, “Oh, my God! What a disaster! What a disaster! What a disaster!” The first person who came backstage was a friend of Jean Cocteau, a famous actor. The name escapes me, but it doesn't matter right now. He comes and he sees me and says, “Menotti, that silence at the end! What a stroke of genius! How marvelous!” [Laughter] And all of a sudden I heard everyone screaming in the audience, so of course we presented it as though it had been planned that way. But then we had a meeting for the second performance. Should we do the silence again? I said, “No. It worked that night because the electricity was so high, but never again. Let’s not do it.”

BD. Can you, as a composer, account for different reactions of different audiences to the same work or even the same production on different nights of a run?

GCM. A work can be interpreted in many ways. That is an old fight I’m still waging now, with all those stage directors that think they can do anything they want to a work. Do you know what Jean-Paul Sartre said in his book about art? He said, “A work is finished by the audience; a book is not finished until it is read.” So actually the audience finishes the work. The music, your music, lives in other people’s ears. So actually every performance is different because the audience receives the opera in a different way.

BD. And this is a good thing?

GCM. Yes, and it’s very important, as long as it is received, because if it is not received, it doesn’t matter how perfect is the performance. If you are not able to reach the audience, then you might as well forget it and not write for the theater.

* * * * *

BD. Coming back to that Puccini story, would you rather have perfection or heart?

GCM. Oh, heart. [Laughter]

BD. Is there ever a chance that you get perfection?

GCM. Perfection actually does not exist. I always mention the wonderful phrase of Paul Valéry: “A work is never finished; it’s just abandoned.” So we know that nothing is perfect, and, of course, an interpretation is never perfect because it is felt by another person. It’s never what actually you felt. But as you write, you know that you’re speaking to another person, and the other person must understand. People say, “I only write for myself.” That’s a stupid thing to say because then you only have a half-finished work. The work will only be finished when it is heard, so as you write an opera, especially for the theater, you must leave room for the person who has to finish the work for you, who has to receive it and feel it in its own way. And it’s never the way that actually you wrote it.

BD. Never?

GCM. No, never. It’s always a little bit different. Sometimes I say, “Oh, why such a slow tempo?” Or I will say, “It’s the wrong tempo actually,” but that person makes me feel that it will work because he feels it that way. He really feels it deeply that way, and finally he convinces me that it is almost the right tempo, although it is not my tempo.

BD. I see. So you’re willing to be convinced, then, by a lot of different ideas.

GCM. Yes, you have to. You have to. When people asked Wagner what was the right tempo for some of his music, he said, “There is no right tempo. Just listen to the melody, and you must go with it.” Also with different generations the feelings of what is presto or what is adagio changes a little bit. For example, for me now, all Chopin is played too fast. To me, when I hear some of the pianists today, the way they play Chopin is almost like Mickey Mouse. I remember the old pianists that had much more leisure. Their allegros were much more leisurely.

BD. Are you advocating that we get back to that?

GCM. Probably. Maybe things will change again. The important thing is that the person who receives the message must try to interpret what is on the page. He receives a proposal, a question, whatever you call it, and he must try to understand it. But I will not condone those interpreters who try to make the work their own. That, I think, is a rape of a work.

BD. So the composer’s name should always be on the top, not the producer’s.

GCM.

Of course, of course. These stage directors nowadays that think

they

can just take an opera and change all the historical background, all

the

tradition that goes with it, should not be allowed. There should

be a society for the protection of composers.

GCM.

Of course, of course. These stage directors nowadays that think

they

can just take an opera and change all the historical background, all

the

tradition that goes with it, should not be allowed. There should

be a society for the protection of composers.

BD. [Laughs] Well, you have produced many or even all of your works. Are there times when you’re producing your work that you, the producer, fight with you, the composer?

GCM. All the time, yes.

BD. Who wins?

GCM. Very interesting. I try to let the composer win, which I think is a lesson to stage directors, because I never write down my stage directions. As a matter of fact, whenever I stage an opera I try to do it with a new eye and new ears. I try to remember what I thought when I compose. There are certain passages where something has taken place. If I think, "It’s so long. I wish I made it shorter," then I say, “Well, there must be a reason why I composed it. I must have visualized something.” And finally I discover why I wrote the music, what I thought at that moment. I think that’s what every stage director should do. Beethoven's Fifth Symphony interpreted by Furtwängler, is very different from that of Toscanini, and that of Toscanini is different from that of von Karajan. And they all think they are doing it the way Beethoven wanted, but of course they received it in a different way. And the same thing is true for the stage director of a play.

BD. I assume, though, that you would not want someone to simply recreate your staging of any one of your operas.

GCM. No, no, no. No, no, the theater allows for that. The interpretation can be received in different ways. I can imagine that, but still with the intention of interpreting my message and what I wanted to say and respecting also the atmosphere which I created, which my music creates. But I don’t want it to be mere repetition. For example, I love the remark that was made by somebody when they heard Peter Sellar’s Don Giovanni. There was an old lady who said, “Oh, that was the most exciting evening. What a shame that the music was so old fashioned.” [Laughter]

BD. Then where is the balance? Or where should be the balance, in opera, between the music and the drama?

GCM. The music is the one that dictates it, absolutely. That, we all know. An unmusical stage director just would never be able to direct an opera well. That’s what makes me very impatient when I go to the theater and sit down and see... For example, when you hear Wagner, he’s so descriptive. When the music says “WALK!” and you see the singer standing, then the music says “JUST SING AND DON’T MOVE AT THIS MOMENT,” and then he goes all around, tearing at his hair or picking at his nose or whatever, you’ll get angry because you know that the stage director is very unmusical and does not listen to the music. The music can tell you, can practically describe for you the movement if you listen to it well.

BD. So the stage director, then, is working from the text rather than from the score.

GCM. Yes, very often, very often, alas, alas.

* * * * *

BD. I assume that you are asked to write all kinds of new things. How do you decide which commissions you’ll accept and which commissions you’ll turn aside?

GCM. I’ll answer you the way Stravinsky did: I accept commissions when I need money. [Laughter] Alas, we composers are always broke. That’s why probably I’ve written so many operas, because people keep commissioning me for operas, and I wish they would commission me to write a string quartet.

BD. Would you rather go back to some instrumental music?

GCM.

Yes, I’m dying now. I think that I have said what I want to say

in

opera. I don’t think I’ll write another one. I’d like to

write

chamber music, also because in a certain way, in chamber music you are

apt to hear your works played much better. I mean they rehearse

more.

There’s not all the hysteria that you have in the theater. You

give

your music to people who really want to handle it well and with care

and

with love. In the theater, too often there are not enough

rehearsals

or then one of the singers gets sick or the music is ready but the set

is off or the lighting is wrong. There’s always something

wrong.

There are too many “ifs.” And so very often, even if you get a

good

first performance, then the second performance you have all the singers

who have not rehearsed with you, and it’s too much of an agony.

GCM.

Yes, I’m dying now. I think that I have said what I want to say

in

opera. I don’t think I’ll write another one. I’d like to

write

chamber music, also because in a certain way, in chamber music you are

apt to hear your works played much better. I mean they rehearse

more.

There’s not all the hysteria that you have in the theater. You

give

your music to people who really want to handle it well and with care

and

with love. In the theater, too often there are not enough

rehearsals

or then one of the singers gets sick or the music is ready but the set

is off or the lighting is wrong. There’s always something

wrong.

There are too many “ifs.” And so very often, even if you get a

good

first performance, then the second performance you have all the singers

who have not rehearsed with you, and it’s too much of an agony.

BD. If you were to hit the lottery and never need for money again, would you stop composing?

GCM. Oh, no, no, no. [Laughter]

BD. That’s good.

GCM. I wish I could! I’ve explained it to my son, and he says, “I understand how much you’re suffering when you’re composing.” In a certain way, I would say that I do my festival to escape the torture of composing. Very often I do things just so that I don’t have to compose.

BD. Is the torture a necessity, or is it a byproduct?

GCM. It’s a necessity, but very often what is necessary is also not the most pleasant thing to face. A composer always looks for something that is unobtainable. We look for sort of an ideal perfection, of what we call beauty that we don’t even know what it is, so it is a struggle. If you really think how mysterious art is... When you read the aesthetiticians — and I include practically every philosopher from Plato to Adorno — and they talk about music, it’s all sort of nonsense because even the musician doesn’t know what music is. Very often when I’m composing, I struggle. “Should this be a B-flat or a B-natural?” I reply to myself, “Who gives a damn whether it’s just going to be a B-flat? Why do I struggle so much? It’s so stupid.” But, alas, you struggle. You struggle to satisfy an inner thirst for this sort of Platonic perfection, of which you have a glimpse, a vague glimpse. When people ask me what I thought about when writing music, I always say: “It is the inevitable.” I think great music is what is inevitable. Like, Schubert is inevitable, Beethoven, Chopin—inevitable. When music is not inevitable, it doesn’t interest me.

BD. While you are composing, are you always controlling where that pencil goes, or does the pencil sometimes guide your hand across the page?

GCM. Oh, very often the pencil guides. Those are the wonderful moments when all of a sudden... well, what you call inspiration, when you are inspired, then there are moments of great joy. But if you think about Brahms or Rossini who went years and years without writing a note. I always think the composers are like the people who search for water with a stick.

BD. Oh, a divining rod?

GCM. Yes, the divining rod. They just go and go and search and search, and suddenly the rod begins to shake, and they say, “I have it! There it is!” Then you start digging, hopefully to find the water, and when you find it, it’s a great moment. But some people just go around forever, and the rod never shakes. [Laughter]

BD. I’m glad your rod has shaken a great deal.

GCM. Well, I don’t know. Oh, no, no, I wish it had shaken more. [Laughter]

* * * * *

BD. What advice do you have for others who would like to write for either the concert hall or the opera stage?

GCM. Oh, I don’t have advice for composers. It’s very difficult. I would say my advice to other composers is beware of your teachers, because I think there’s a lack of good teaching today.

BD. What advice do you have for audiences?

GCM. I wish one could teach audiences what to like and what not to like. [Laughter] First of all, what is an audience? There are so many different kinds of people in an audience. Certainly one of the first things I would give an audience is not to let themselves be influenced by what they read in the newspapers. I think especially in America, people are much too easily led by what the critic says the next morning. They need to have the courage really to like or to dislike what they like and what they dislike, and not to pretend to like what they really don’t, and vice versa. That is something that always irritates me. And to understand the one thing that I think is fundamental in art. I’ve always been against those courses that they call "Art Appreciation." Art doesn’t have to be appreciated, it has to be loved. What the composer and artist wants is love, just as a woman doesn’t want to be appreciated, she wants to be loved. It's the same thing. Art needs your devotion, and it has to be not something that has been taught but something that has been felt. Then you appreciate different things later on, but the first thing is you must be sincere with yourself. Do I love this music? And if you are attracted by that, just like a person, I meet you, I like you, and so I’m having a nice discussion with you. If you were somebody that repulsed me in a certain way or I find unsympathetic, I probably would not be sitting here talking to you the way I do now. And I think that the first thing is really to establish this sort of relation to a person. If you don’t like something, don’t pretend that you like it. But unfortunately, so many in the audience just read in the paper that that is a masterpiece, so they go. They sleep all through it, and then they say: “Oh, it was marvelous.”

BD. But I assume you want people to give anything a chance.

GCM. Yes, but also there ought to be adventures to try all sort of things. Like in life, you just don’t sit always with the same three or four friends; you go out and try to meet other people, different kinds of people in order to discover. For example, I remember I never wanted to meet Jean Cocteau because I thought he would be a terrible poseur and an unbearable snob and so on. But when I was in New York, a friend called me up and said, “You know, Jean Cocteau would like to meet you.” And so I went. Of course I went. Then we became the best of friends, because, yes, he was a terrible snob and a terrible poseur, but he was also a very charming person. After you met him and were with him for half an hour, he knew how to enchant you right away. I think it is similar with art. You just have to give him a chance, yes, but don’t force yourself. If you finally meet the person and still you think he is a fraud, just have the courage to say, “For me, it’s a fraud.” I shock people because I say I don’t like Bartók. They say, “Oooh! You cannot say that.” Why can’t I say it? I just don’t like Bartók, that’s all. They say, “Oh, but the quartets...” Well, I think his quartets are a big bore. Everybody absolutely faints with horror when I say that, but I know many people that really feel exactly the way I do; they just don’t dare to say it.

BD. But you don’t wish to stop other people who enjoy them from enjoying them.

GCM. No. Of course, of course not. Heavens no.

BD. So you include them, but you just don’t want to include it in your own life.

GCM. Exactly right. As a matter of fact, in my festivals (now I have only one festival because one I gave up), I don’t always do the music that I like, I do a range of music. As long as I think it is not a fraudulent art, I give it a chance. We do all sort of things. I don’t have to go and hear it if I don’t want to. The secret of the Spoleto Festival is that it doesn’t mirror my taste only. I try to give a chance for people to hear all sort of things.

BD. Thank you, Maestro. Thank you for all of the operas that you’ve given us, and I look forward to string quartets and other chamber music to come. I very much enjoy some of the older concert music, the Piano Concerto and the Violin Concerto and the harp piece...

GCM. Well, thank you for your patience.

=== === ===

-- -- --

=== === ===

Two years later, in the

fall

of 1995, Lyric Opera presented The Consul.

Menotti was again in Chicago

and asked to speak with me one more time.

GCM. They’re doing The Consul, but I’d much rather speak about the festival and Spoleto and things in general. We also could speak about The Consul if you like.

BD. That’s fine. To start, you were mentioning that one conductor is sort of cold and you don’t particularly care for another conductor. Are you able to arrange for the right conductors for your operas most of the time?

GCM. Indeed not. It is very difficult to find a conductor that would satisfy almost any composer, because when we write music we hear it, of course, and we know what the tempo should be, we know where we would like to have a little bit of a ritardando, where we would like a bit of this and that, and we don’t always write it down. The only composer who wrote everything down probably was Debussy. Debussy always writes everything down, and he was right. Wagner, in some of his writings says, “When people ask me about what tempi my music goes, I always say, ‘Just look at the music. The music tells you what the tempo should be.’” And I always feel the same way. I am more surprised when I hear a composer taking the wrong tempo for my music. It seems to me so obvious what the tempo should be.

BD. Is there only one tempo that it should be, or is there any flexibility at all?

GCM. There is flexibility, of course, if you can be convinced. Take it a little bit faster, but there is an ideal tempo, more or less. Actually, I remember when Toscanini told me that when he was a young man he wanted to meet Verdi, and I think it was the only time he actually met Verdi. He was about to conduct the Requiem, so he got an appointment to see Verdi. Of course, he was very excited and very nervous, so Verdi asked what the conductor wanted to know, and Toscanini said, “Can I go to the piano and just play for you a little bit of it, for the tempi?” Verdi agreed, so he sat down, played the passage, and made a ritardando which was not written in the score. Then he stopped because Verdi just didn’t say anything, and he said, “Maestro, I made a ritardando.” And Verdi said, “Yes.” “But it’s not written in the score.” And he replied, “But aren’t you a musician? Of course you would do a ritardando there. In fact, if I had written a ritardando, you would have made too much of it. This way, I take it for granted you know that that has to be slower.” And I feel the same thing about my music. Perhaps it’s a sign of the times, but I feel there is a tendency nowadays that people always come too soon on the downbeat. They always go, “Tah-dah-dah-rah-POM.” They don’t breathe, they don’t let the phrase finish and then begin the next one. That is very bad, especially in opera, because of the words they are saying. They must give time for the words to be said, and when there is a comma in the words, in the phrase, that should also be felt in the music.

BD. Feel the punctuation.

GCM.

The punctuation, yes. For example, now I’m about to stage the

coming

Spoleto Festival. I’m going to be eighty-five next July, and my

son

[in photo at left], who is the president of the festival, said, “We

want

to give you a present. Why don’t you stage an opera, one of your

favorite operas?” I said, “I don’t want to stage anything more of

mine, but maybe I will stage Eugene Onegin because I love Eugene

Onegin.” So we are doing it. You really have to breathe

not only with the music but you have to breathe with the words.

GCM.

The punctuation, yes. For example, now I’m about to stage the

coming

Spoleto Festival. I’m going to be eighty-five next July, and my

son

[in photo at left], who is the president of the festival, said, “We

want

to give you a present. Why don’t you stage an opera, one of your

favorite operas?” I said, “I don’t want to stage anything more of

mine, but maybe I will stage Eugene Onegin because I love Eugene

Onegin.” So we are doing it. You really have to breathe

not only with the music but you have to breathe with the words.

BD. So you’re breathing with Tchaikovsky and with Pushkin.

GCM. And Pushkin, obviously. You cannot just listen to the music, you must know what the words are saying.

BD. You’ve done all of your own librettos, have you not?

GCM. Yes.

BD. Are there times when Menotti, the composer, has fights with Menotti, the librettist?

GCM. Yes, but that takes place while I’m writing the opera. [Laughter]

BD. But, then, as we get the score with the finished libretto in it, there’s only really one authorship for it. We are breathing with you, breathing with your music and breathing with your words.

GCM. Yes, of course. I just had auditions and I find that many of the singers, perhaps because they think that by singing my music I’m going to give them the job [laughter], they always bring my music, which makes me very nervous. And I noticed that all of them sing the things too fast. They don’t let the phrase breathe with the words, and they are afraid of silence. In my music especially, especially in The Medium and The Consul, the silences are just as important as the sound. I’m a great believer in silences, and most of contemporary music has no silences; it’s always a noise and goes on all the time. I learned that from Beethoven in his marvelous “Dah-dah-dah-DAAAH [the opening notes of the Fifth Symphony].” Silence. “Dah-dah-dah-DAAH.” [Whispers] Silence. All through his music are these marvelous dramatic silences, and I made use of that very much, especially in The Consul and The Medium.

BD. Should there, perhaps, be a letter from the composer to each conductor printed on the flyleaf of the score?

GCM. I always say, “Please, when I ask for a long silence, I mean a long silence.” But the performers are afraid. They are afraid. When they get to a silence, even when I’m there and I say, "Now, silence. There’s silence. Don’t be afraid.” They say, “But Mr. Menotti, I have to sing.” I say, “Yes, but wait, wait, wait, wait. Let the audience wait.” It’s very difficult to teach that, but when they finally get it, then they understand it.

BD. Is there any chance at all that the singers might know, perhaps, more than the composer about the feeling and the pace of the audience coming to performance that night? You composed these things thirty, forty, fifty years ago for certain audiences and certain times and certain heartbeats and certain lifestyles.

GCM.

No. Both with The Medium and The Consul, I’ve

tried

those two operas with so many audiences, and I know. There are

certain

moments... For example, in the first act of The Consul,

when

the chief of police comes and says to Magda, “When did you see your

husband

last?” And she doesn’t answer. Then he says, “ANSWER

ME!”

Now, the way they generally do it is they say: “Have you seen your

husband?

When did you see your husband last? ANSWER ME!” I say,

“No!

Wait!” They always say, “Mr. Menotti, but I did it that

way.”

“But you didn’t do it long. You must feel the

audience.

If you say, ‘When did you see your husband last? [Pause]

ANSWER

ME!’ Then it becomes a dramatic moment, but if you don’t wait

that

long, the thing that is important is to have the silences, to stretch

it

as long as you possibly can. When you feel it’s too much, then

you

do it.” The audience itself must say, “Is she going to answer or

isn’t she going to answer him?” Those are very important

silences.

The same thing in The Medium. There are countless moments

where I put “a long pause” or “a long silence.” They never do

it.

They never do it, but they do it with me. [Laughter]

GCM.

No. Both with The Medium and The Consul, I’ve

tried

those two operas with so many audiences, and I know. There are

certain

moments... For example, in the first act of The Consul,

when

the chief of police comes and says to Magda, “When did you see your

husband

last?” And she doesn’t answer. Then he says, “ANSWER

ME!”

Now, the way they generally do it is they say: “Have you seen your

husband?

When did you see your husband last? ANSWER ME!” I say,

“No!

Wait!” They always say, “Mr. Menotti, but I did it that

way.”

“But you didn’t do it long. You must feel the

audience.

If you say, ‘When did you see your husband last? [Pause]

ANSWER

ME!’ Then it becomes a dramatic moment, but if you don’t wait

that

long, the thing that is important is to have the silences, to stretch

it

as long as you possibly can. When you feel it’s too much, then

you

do it.” The audience itself must say, “Is she going to answer or

isn’t she going to answer him?” Those are very important

silences.

The same thing in The Medium. There are countless moments

where I put “a long pause” or “a long silence.” They never do

it.

They never do it, but they do it with me. [Laughter]

BD. Maybe we should put a copy of this interview on a little diskette with each score, and then they would know that it’s right from the composer’s idea.

GCM. Perhaps... I feel another example in Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin. The letter scene is always sung so quickly, and she has so many phrases in there. I know I would have trouble with the conductor and with the singer, with Tatiana, because I want to really say the words even if you stretch the music a little bit. But if you follow the words, then the letter scene will not become boring. It becomes a little bit boring when they repeat things so many times, but there should never be a repetition of the phrases. Each phrase says a difference thing.

BD. She has to be composing the letter in her head.

GCM. The letter is in her head, so it must have a feeling of little pauses. I think it’s very important. I don’t know whether I succeeded in getting what I want out of my very young Tatiana. I insisted on getting a singer that looks sixteen, and I was giving up trying to find one because either they are too old to look like a Tatiana or they are too young to sing well, and I was just giving up. Last night I had auditions all day in New York and the last singer that came in was this young girl, thin, very innocent and charming, and I thought, “Oh, my gosh, I’m sure that she has a terrible voice." And lo and behold, this lovely golden voice came out of her. I practically kissed her I was so happy.

BD. Did you relate to her how much you had listened, how long you had waited for her?

GCM. She’s a young Russian girl. I won’t tell you the name because I don’t want anybody to steal her from me. She never sang in America, and she will make her debut at the Spoleto Festival.

BD. Will this be in Italy or in America?

GCM. There’s only one Spoleto, and that is in Italy. The one in America doesn’t exist anymore.

BD. Will the Eugene Onegin be sung in the original Russian or in Italian translation?

GCM. No, in Russian, Russian, Russian.

BD. Do the Italian theaters have the gimmick of the super-titles?

GCM. Yes, now in Italy, even at La Scala they have the super-titles sometimes.

BD. Do you believe in those?

GCM. Well, I think yes. I was always against them because I think they do distract the attention. But still if somebody wants to really enjoy an opera and let themselves be involved in the action, he should read the libretto first and then you really can enjoy the music without having to look up and down all the time. But at the same time I also saw that the audiences used them. I did Meistersinger in Spoleto two years ago and I was a bit nervous. You know it is a long opera, and especially the first act is very long. But by having the translation and by having a long intermission—I had almost two hours between the first and the second act so people could go out and eat and come back—many people in the audience came back to hear it three, four times, which for Italians is very unusual.

BD. You say you want the audience to enjoy it. Is this the aim of opera, to induce enjoyment on the part of the public?

GCM. Well, “enjoyment” perhaps is not the right word, but involvement. I think Goethe said that anything is right on the stage; everything can be done on the stage as long as it creates an atmosphere that involves you, as long as you are part of what’s happening on the stage. If you are not involved and you just look at it, you miss the point. That is why I always think that critics never really, cannot possibly enjoy a work of art the way it should be enjoyed or understood, because they don’t let themselves go and be taken in by what happens on the stage; they are judging it all the time. So that’s wrong. You know the wonderful French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre wrote a wonderful book about art, saying that a work of art is always unfinished. The person who receives it actually finishes the work. A book is not finished until it's read. A piece of music, unless it is heard, is unfinished. So actually you must become part of the work of art to receive all its message. If you resist it and say, “I want to judge it,” then you don’t receive the whole message.

BD. I don't enjoy doing criticism, and have not done any for many, many years. It’s so nice to go to a performance just to enjoy it and not have to scribble afterwards.

GCM. To scribble, of course. It’s a completely different way of receiving the message of the artist, of the creator.

* * * * *

BD. How big a theater is in Spoleto?

GCM. We have two theaters. Actually, we have three theaters. We have an eighteenth-century, lovely, small theater, only about 300 seats.

BD. What goes there?

GCM. This coming summer we’re doing Semele of Handel. And then we have an early nineteenth-century theater, a very beautiful one, of 900 seats, actually almost 1,000. There, we do the Tchaikovsky, we do the big works, we do Wagner. You have no idea, Meistersinger or Tristan, how they sound in a small theater like that.

BD. I think it would be wonderful.

GCM. Ah! It’s a completely different experience, with the rich orchestration in a small theater. It has wonderful acoustics; it’s all wooden. It’s almost too much.

BD. Now, which of these two theaters should your works be performed in? Would The Consul be better in the 900 seats or in the 300?

GCM. Oh, the 900. It needs that space, yes.

BD. Then we come to Chicago, where we have four times that amount of seating.

GCM.

I know. I’m very nervous about that, because if it was The

Saint

of Bleecker Street, which has rich orchestration and is made for a

big theater, or The Last Savage... The Consul is

meant

to be a more intimate sort of a work. It’s very sparse

orchestration,

but it’s strong enough to make its point even in a big house. It

has been given at La Scala, in the Staatsoper in Berlin, in Vienna.

GCM.

I know. I’m very nervous about that, because if it was The

Saint

of Bleecker Street, which has rich orchestration and is made for a

big theater, or The Last Savage... The Consul is

meant

to be a more intimate sort of a work. It’s very sparse

orchestration,

but it’s strong enough to make its point even in a big house. It

has been given at La Scala, in the Staatsoper in Berlin, in Vienna.

BD. Do you do anything to it to alter it, to spread it out just a little bit and make it larger, or do you just let it stand?

GCM. No, I let it just stay. Anyway, in most operas, their orchestrations are always too loud and they cover the singers. In these concerts it’s very important that the people can follow the texts, so instead of all the screaming of the conductor to keep the orchestra down, I might as well have a smaller orchestra. It’s easier.

BD. Does it please you that a house the size of Chicago will give several performances of Consul?

GCM. Yes, I’m very pleased, of course. I’m only just sad that they didn’t let me stage it. I would have loved to have staged it.

BD. Do you have ideas about putting it into a big theater?

GCM. I have. I have many times. I did it at La Scala which is a huge theater.

BD. What kinds of things change from a 900-seat theater to a 4,000-seat theater?

GCM. First of all, you need much bigger voices, of course. Magda can be sung by a lyric or spinto in a small theater. In something like La Scala, you have to have a real dramatic soprano.

BD. An Aïda-type?

GCM. Yes, to make it work. And it's the same thing, the chief of police has got to be a bass like Ramey. Then the woodwinds and the brasses are very small; it’s a small orchestration. I don’t remember exactly what it is, but when I gave it in New York, in a small theater, it was with a very small string orchestra. In a big house, I hope they’re going to use the whole string section, even though the woodwinds stay where they are.

BD. No doubling of the winds?

GCM. I don’t think they need to, no. Most conductors think to make lots of noise they’ve got to have a big orchestra, and they do. [Laughter] But I think you can have some wonderful pianissimos like Toscanini used to have, with a huge orchestra, and you can have really big fortissimo with a small orchestra if you know how to use it.

BD. I would think that having wonderful pianissimos would then make the impact of the fortissimos more.

GCM. More, of course.

BD. Does the large theater automatically make the conductor take a little more time, make the pauses a little bit longer, as you want?

GCM. I hope. I hope. I’m going to meet with the conductor soon, and I’m going to tell him where I want all those pauses, and I hope that he will obey me.

BD. Have you ever conducted yourself?

GCM. No, I never have.

BD. Why not?

GCM. Never interested me, really. I like staging it. First of all, I don’t because there are an awful lot of good conductors around, decent conductors anyway, and a few great ones. But there are so very few good stage directors for opera who really stage the music and not only the libretto. I got very impatient with my opera, and I got impatient when I go and see the staging of other composers’ operas when the music clearly says: “Walk,” and they just stand there; then the music says: “Don’t move now, just sing, don’t move,” and they start going around. Oh, my God! Can’t you listen to the music? How can a person move at that moment, when the music said: “Don’t move, just sing, and don’t move at that moment”? They don’t listen to the music. Just like dancing. I mean, if you notice how very few dancers really dance in time with the music, they always put down their foot either too soon or too late. [Laughter] Except Balanchine. Balanchine really was a very punctilious about following the music.

BD. Is there anything else that we should know about The Consul here in Chicago, for Chicago audiences?

GCM. I think as far as I can see, it has a very good cast. I do not know the Magda, but I hear she's very good. I know the other singers and I think that’s a very good choice.

BD. What should audiences know about this specific opera before they come to it?

GCM. Nothing, really, because it should be self-explanatory. It should awaken in the receiver a sort of indignation, which is the main emotion of the opera. It still works that way. The last performance of The Consul that I staged it myself was in Monte Carlo, and I was nervous because how could this audience of all these rich people that are retired know, what would they know of such problems? But it worked incredibly, because actually so many of those so-called rich people have been Jewish people that had to escape. And then the hatred of bureaucracy is in all of us, and the injustice of the way bureaucracy steals our time and our freedom, and this sort of blind obeisance of silly laws. Actually, at the moment when she says, “Burn the papers,” everybody goes, “Ah!” Even people who have not suffered the indignation of having to find a passport and being questioned on everything, even so, everybody has sort of this sense of protest toward the paper chase.

* * * * *

BD. You’ve supervised some of the recordings that have been made of your works, have you not?

GCM. Let’s not talk about recordings because I have so very few of them.

BD. Well, my question really is: If you get a recording that you feel is right, should that serve, then, as a model for all future productions, and would that perhaps put the future performers in a straightjacket?