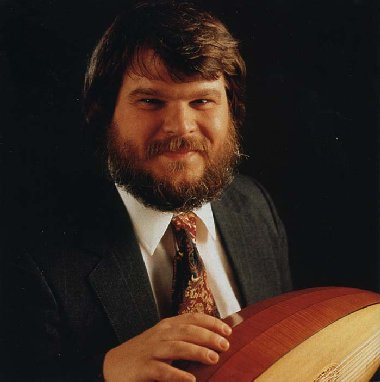

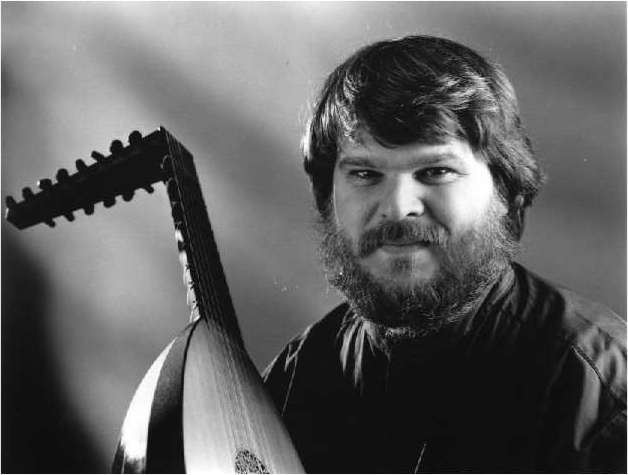

Lutenist Paul O'Dette

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Lutenist Paul O'Dette

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

When one is in the Classical Music Business, most of the players tend to favor the works that will get numerous performances with a variety of audiences in multiple cities. For good or ill, this generally means the Big Romantic Stuff. And while I love all of that and would never want to live without it, I am always trying to expand the repertoire in both directions - older and newer.

Listeners to my radio programs and readers of my website know of my devotion to the living composer, but I also have a great fondness for those who unearth the older music and perform it with as much historical accuracy as is known. It's been my pleasure to meet and chat with a few of the practitioners of this growing field. My list of guests includes names under such instruments as Recorder, Gamba, Counter Tenor (yes, many singers consider their voice an instrument), Baroque Trumpet, and Lute. One of the very best exponents of the Lute is Paul O'Dette, and his visits to Chicago are always anticipated and his recordings sell very well both here and around the globe.

As you will see in this conversation, O'Dette has a deep interest in his specific field, and also knows the historical context of its creation and, now, its current performance. I always learn a lot when conversing with the top musicians of the world, and this was certainly no exception. His range of knowledge and his ability to put things into perspective is quite amazing, and I'm very pleased to share this, now, with another audience on the internet.

As we were setting up, I told him a bit about WNIB and how I was

constantly

striving to present various periods and styles, from the distant

yesterdays

right up to the latest advances. It was the totality, the broad

range,

that had always fascinated me, and I commented that it was lots of fun

. . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Is playing the lute lots of fun?

Paul O'Dette: Oh, yes. It's always entertaining.

BD: [Chuckles] Entertaining? How?

PO'D: Well, the music is fascinating. There's an enormous amount of very, very fine music in a wide variety of styles, from the simplest dance pieces, which are very tuneful and rhythmic, to the most complex fantasias, and arrangements of motets and madrigals and mass movements. It's a repertoire which spans the late 15th century to end of the 18th century.

BD: When you get a piece of music in your hand, is there enough notation for it, or are your required to put in a lot of the ideas and thoughts, and perhaps even some of the notes?

PO'D: It depends on the repertoire and the style. Some of the music is very carefully notated, and everything is indicated, including the ornamentation and the right- and left-hand fingerings. In other repertoire all you have is a skeleton, and the performer is required to add ornamentation and to improvise.

BD: Do you prefer one over the other?

PO'D: No; I think they're different mindsets. I guess I have a slight preference for the improvisatory side where there aren't any rules and one can just allow one's fancy to run wild, depending, of course, upon one's understanding of the style. But there's a certain freedom involved in that, which I slightly prefer to having to play exactly what's written on the page. But the other is usually an indication of music of the highest quality.

BD: So the composers of the Renaissance period knew what they were doing as far as this particular instrument?

PO'D:

Oh, absolutely. The lute was by far and away the most popular

instrument.

It was the instrument not only of the court virtuosi, many of whom were

the most highly regarded, highly revered, and also highly paid artists

of any kind - that includes painters - of the 16th century. In

one

case, lutenist Alberto da Ripa was the second most highly paid member

of

the French royal payroll, after the Minister of Defense. So the

level

of playing was extraordinarily high, I think probably only comparable

to

the level of playing the piano in the late 19th or early 20th

century.

It was an instrument that everyone played. If you were a

well-educated

individual you could at least play a few simple pieces on the lute,

just

as was expected earlier in this century of a person, who didn't have to

be a musician, but if you're relatively well-read, cultured, educated

individual,

you can play a few pieces on the piano. That's unfortunately no

longer

the case, but it certainly was at the beginning of this century.

There were so many people playing, and the level was so high, that I

think

one can safely say, is well beyond that of any of the players around

today.

There's music that the best players today couldn't even contemplate

trying

to learn, because it's so difficult.

PO'D:

Oh, absolutely. The lute was by far and away the most popular

instrument.

It was the instrument not only of the court virtuosi, many of whom were

the most highly regarded, highly revered, and also highly paid artists

of any kind - that includes painters - of the 16th century. In

one

case, lutenist Alberto da Ripa was the second most highly paid member

of

the French royal payroll, after the Minister of Defense. So the

level

of playing was extraordinarily high, I think probably only comparable

to

the level of playing the piano in the late 19th or early 20th

century.

It was an instrument that everyone played. If you were a

well-educated

individual you could at least play a few simple pieces on the lute,

just

as was expected earlier in this century of a person, who didn't have to

be a musician, but if you're relatively well-read, cultured, educated

individual,

you can play a few pieces on the piano. That's unfortunately no

longer

the case, but it certainly was at the beginning of this century.

There were so many people playing, and the level was so high, that I

think

one can safely say, is well beyond that of any of the players around

today.

There's music that the best players today couldn't even contemplate

trying

to learn, because it's so difficult.

BD: And yet we assume that the level of playing, at least on modern instruments, is much higher today than it was, say, 100 years ago. So how do you account for this discrepancy?

PO'D: Well, I don't think that that's actually true. It's a common modern fallacy to assume that we're getting better and better. We're able to do different things now than one was able to 100 years ago, or one was able to do 400 years ago. I wouldn't suggest that a lutenist today could play the most difficult classical guitar music. The techniques are completely different especially the right hand technique. The things that one is required to be able to do with the left hand are quite different. But the techniques that they did develop were things that people played or used from the time they were four and five years old, and they had the best instruction available. The reason that people are not able to play the most difficult Renaissance lute pieces today, or even the most difficult trombone pieces or viola da gamba pieces, or even some of the early 17th century violin music, which is extraordinarily difficult, is that the techniques are no longer applied. They're no longer used in the repertoire that people play, or spend most of their time working on today.

BD: So we learn to play differently

PO'D: That's right.

BD: Okay. Should there be a school where you learn to play in the Renaissance style?

PO'D: [Without hesitation] Oh, I think there should be. I think one of the curious aspects of the revival of early music over the past 20 years is that it has only been possible because of a handful of truly brilliant people who have worked very hard and taught themselves how to play their instruments, and have brought it to a level which is good enough that they can pass it on to the generation. But what is really needed is some institution to decide that they're going to promote the study of early performance techniques and early instruments, so that people are able to pass on this information. As it stands now, with the exception of two or three schools in Europe, there's no place to go to study these instruments. Most people learn by starting out on their own, reading a few articles or books, going to some summer workshops, and practicing a lot, and a lot of trial by error, whereas the 16th-century lutenist had the opportunity to study with John Dowland or Francesco da Milano from a very, very early age.

BD: And all of this has been lost over the years?

PO'D: All of it's been lost, the same as the art of making violins has been lost since Stradivarius. I think one always has to keep in mind that if, as one is often led to believe, we're so much better in so many areas than people were in earlier periods, then why can't violin makers make instruments that are as good as the violins that were made in the 17th century? There are many reasons for that, but one of the reasons is that the secrets that were handed down from generation to generation have been lost. And it's the same with technical secrets on a lot of these instruments. We're really still in a learning stage. One thinks of performances on so-called original instruments 20 years ago, with wind instruments being out of tune and string players scraping away, and lute players buzzing on every other note. Certainly the standards are a lot higher today, but I wouldn't pretend for a moment that we're anywhere near the standards that I think existed at the time.

BD: Are we going to be able to approach them in your lifetime?

PO'D: [Exhales audibly, possibly out of consternation in pondering this question, thinks for a moment, then answers somewhat hesitantly] I don't know. I think it will certainly get better as long as there is an audience and there's an opportunity for people to study. Whether or not we can recover all of the secrets I think is probably unlikely, but we'll probably develop new ways of solving some of the problems. For instance, one of the problems we have in the area of lute playing is that originally one played on very, very high quality gut strings that were made in ways that we don't know about. We know that the techniques of string making have been lost. We know that the strings were far superior to anything that is available today. I won't get into the details how we know that, but suffice it to say we do know that they had considerably better strings then, than we have now.

BD: Better, or just different?

PO'D: In the case of gut strings, it was better, because the tradition was completely lost in the early part of this century. When people went to playing string instruments on metal strings, all of the trade secrets went to the graves with the great string makers. Also, in a curious sort of way, technology has been our enemy, because a lot of things that are done today which make string making easier actually produce lower quality strings. The old techniques of making gut strings involved separating each membrane of the intestine and hanging it up to dry, then twisting each one individually. That's very time-consuming. What modern string makers do is take a big chunk of intestine and force it through a die, which cuts the fibers into much shorter sections. This means that the strings aren't as strong and they're also not as elastic because you have shorter fibers. They tend to unravel, they tend to unwind rather quickly. And they break, therefore, at lower pitches than the earlier strings did. Also, we use preservatives. They started using sulfur in the 19th century which stiffens the fibers, and makes them respond less readily and less immediately.

BD: Now this involves preservatives in the string-making process?

PO'D: That's right.

BD: Is there any chance there's a difference in the actual growing of the animal?

PO'D: That's right. That's the other thing that we know. The strain of sheep that were the most prized for string making no longer exists. Also they tended to use lambs that have just been weaned. That would be far too expensive, even if it were possible. Milk-fed lambs at a very young age when they have just been weaned, before they start eating grass, those were the animals that were used to produce the finest strings. Today, most of our gut comes from two- or three-year-old animals.

BD: Are some of the old strings still extant, so that we can do sophisticated testing on them?

PO'D: There are! I hope this isn't a secret that I'm letting out of the bag too early, but I heard that a colleague of mine in England has recently discovered a very early 19th century guitar, with original strings. There are gut strings all the way down to the A string, which is the next-to-the-lowest string on the guitar, which really quite shocking because on the modern guitar one uses wound strings starting on the fourth. Even those people who play 19th century guitars with gut strings don't put a gut string any lower than the third string. This one has it on the fifth string, and the first five are all solid gut strings. But we're also learning a lot more. There's a man in Italy now who's experimenting with what he thinks is likely to have been the original string-making process for making thick gut strings. He marinates them in various metal salts. This is something which has just been discovered over the last three or four years.

BD: Well, what are we learning from this man who discovered this early classical guitar?

PO'D: It suggests that they were making strings that sounded resonant enough and focused enough, right down to a low A, which is certainly not possible with modern string-making technology. You would have to use some kind of a wound string.

BD: Do you think that modern technology is going to be able to come up with something completely different which will produce the old sound?

PO'D: [Thinks for a moment] I don't know. This is really the problem. The other problem with gut strings today is that they are so susceptible to changes in humidity. If I fly from Chicago to Tucson, for instance, I couldn't possibly use gut strings. I'd never be in tune upon arrival, after a change of 40 percent humidity.

BD: So if you wind up with a lute that has some kind of original-type strings, we should demand that you wander the countryside instead of fly the airplane!

PO'D: This is exactly the problem. If you use gut strings and you stay in one location where the humidity is relatively constant, then they'll stay in tune for a long time. I taught a course in Italy a couple of years ago, and I had my lute entirely strung in gut. I literally didn't touch a peg for three weeks. But today, if you fly from Rochester to Boston, for instance, with gut strings, it takes several days for the strings to settle down. And the modern replacements--nylon, in this case--have such totally different acoustic properties that they really are not satisfactory substitutes. But they're the only substitutes we have if we want to play in tune in the modern life of a touring musician, flying around from one area to another.

BD: Do you envision, perhaps, enough demand, and enough lutenists around, that you can do like the Steinway people, and have instruments staying in each location, or at least in each major location, and have local technicians who will take care of the instruments which you'd use upon your arrival?

PO'D: That would be interesting. A number of us have already talked about that possibility in terms of the long-neck lutes, theorbos and archlutes, which, at anywhere from 5 1/2 to 7 feet long, are a real pain in the neck to travel with.

BD: Literally a pain in the neck!

PO'D: Yes, right, right! [Both laugh] If I'm doing a program with an ensemble, or with a singer, of late 17th century music, I may need a theorbo and an archlute. Carrying around two six-foot instruments that have to be checked because they're far too large to buy a seat, even if one could afford to, these days, on the plane, and trying to find taxis in which you can actually fit the instruments, is always a problem. It would be much easier if we could contact colleagues in Europe and say, "I need these instruments at that location on that date. Could you arrange for them to be there when I arrive?" And then vice versa. We've done a little bit of that, but there aren't enough of us yet to make that really practical.

BD: Instead of taking two separate instruments, would it be easier to pack them in a harp case?

PO'D: I don't think a harp case would be long enough to fit a theorbo. They're awfully long - up to seven feet.

* * * * *

BD: As we head toward the 21st century, how much demand is there for Renaissance lute players and Renaissance lutes?

PO'D: I think that for very good players who are flexible and familiar with a variety of repertoires, not only Renaissance music but also early Baroque music, and can play continuo on a couple of instruments - there's quite a lot of demand. In fact, at the moment there's too much demand for the best players. It's impossible to take on all the work that's available because of the number of performances, especially in Europe, of late Renaissance and early Baroque ensemble music. That is both a blessing and a curse. It's a blessing in that there's a lot of work out there and a lot of possibility for talented players to play a lot of different repertoire on different kinds of lutes. It's a curse because one has the problem of trying to cover all of the music between 1500 and 1750. On the lute, you need a minimum of a dozen instruments in order to cope with all of the different tunings and different types of instruments to fit the style of music that you're playing.

BD: So it's more than a pianist going from Scarlatti to Webern.

PO'D: That's right, it's far more than that because they're playing on the same instrument. Also, a classical guitarist beginning a recital with Dowland and finishing with Brouwer or Henze, it's all the same six-string guitar with the same tuning and the same string spacing. If I play the lute music of the first half of the 16th century, that instrument is different from the instrument that was used in Dowland's time. You can make a compromise by using a late 16th century lute and playing this early repertoire on it, but it doesn't sound very good because the tuning was different. The early lute has octave strings in the bass, and so, in the case of a six-note chord, you lose three of the voices if you try to use a late 16th century lute.

BD: Then when you're setting up your programs, do you specifically try to make it so that at least the first half will all be on one instrument and the second half will be all on, perhaps, one different instrument?

PO'D:

I try to do that. It's a real dilemma because traveling with more

than one instrument is always a problem just in terms of how much

baggage

one has, dealing with the airlines and taxis and so on and so

forth.

I'd much prefer to play entire programs on one instrument. It

makes

traveling a lot easier, but the fact that the music is so unfamiliar to

a lot of people, I usually find that audiences respond better if you

have

an instrument with quite a different timbre. So I'll use, say, an

early 16th century lute on the first half, and play a theorbo on the

second

half, so that there are two completely different sounds.

PO'D:

I try to do that. It's a real dilemma because traveling with more

than one instrument is always a problem just in terms of how much

baggage

one has, dealing with the airlines and taxis and so on and so

forth.

I'd much prefer to play entire programs on one instrument. It

makes

traveling a lot easier, but the fact that the music is so unfamiliar to

a lot of people, I usually find that audiences respond better if you

have

an instrument with quite a different timbre. So I'll use, say, an

early 16th century lute on the first half, and play a theorbo on the

second

half, so that there are two completely different sounds.

BD: So there's your variety - it's in the different instruments.

PO'D: Yes. Of course one tries to use as much variety of timbre and tone color as possible. The problem is that audiences are so familiar with 19th-century music. You can give an entire Chopin recital, or an entire Beethoven recital on the piano, and audiences, if it's played well, will obviously be on the edge of their chair for the entire evening. The lute repertoire is unfamiliar, the instrument has a low dynamic range, and using the whole dynamic range and all the timbral possibilities still is not as large as the contrasts one can achieve on the piano, for instance. The changes are more subtle, and for those listeners who aren't used to dealing on this kind of smaller scale, it's easier if you can give them another instrument for contrast.

BD: For you, personally, is it better or worse, or just different, to play solo, or in consort?

PO'D: I enjoy both. I especially enjoy making music with others because there's nothing like the spontaneity, responding to the way somebody plays something differently from the time before. At least that's part of what I find so fascinating about a lot of this early repertoire. Instead of rehearsing something over and over and over and over again, and saying, "It's going to be exactly like this," and doing only that way every time, it's different every time. Players add different ornamentation, they'll start a crescendo earlier, or an accelerando. They'll do things differently that in ensembles you have to respond to. So in that respect, a lot of this earlier repertoire is closer to jazz than it is to later classical music.

BD: I was just going to ask, is there a perhaps broken but direct link between the Renaissance consort and the small jazz ensemble?

PO'D: Well, a lot of the attitude is quite similar, and the approach is similar in that a lot of the repertoire consists of known-music - that is, popular ballad tunes or dance tunes that were well known, or even madrigals and motets that all of the listeners of the 16th century recognized. They were the hit tunes of the time. You had that as your basic framework and then improvised variations or ornamentations and made your own arrangement. It was the same whether you were playing as a soloist or with an ensemble, because you can have ensembles improvising arrangements of English ballad tunes, or you can have a lute soloist or a harpsichord soloist improvising a set of variations. The thing that's so fascinating about the solo lute repertoire is that because the lute was the most popular instrument throughout the 16th century and a lot of the 17th century, and a lot of the best musicians of the time were lutenists, the quality of the surviving repertoire is extraordinarily high. And there's an enormous amount of it. At last count well over 50,000 compositions for the lute have survived, and that's a number which is much larger than any of us could contemplate being able to get through in four or five lifetimes. [Chuckles] So there is no shortage of truly great music, most of which, incidentally, has never been heard since the decade in which it was written.

BD: Then up pops one of my favorite questions. From this enormous repertoire, how do you decide which pieces you'll play this year, and which pieces you'll play next year, and which pieces you'll perhaps just let go?

PO'D: That's always a problem because one has to choose and make sure that you don't spread yourself too thin. Obviously, the most logical place to start is with the music of the greatest composers: Dowland, for instance; Francesco da Milano, who was probably the greatest Italian lutenist of the 16th century; and to find out who were the most highly regarded musicians of the time and to go through their repertoire systematically, and play as much of it as possible. But one is constantly sidetracked. I discover new things in manuscripts or in lost books that suddenly appear in a library in Poland or Lithuania that no one knew about. You find a marvelous collection of music that hasn't been played in 350 years, and obviously there's a great excitement. One can't resist the temptation to start playing a lot of that repertoire.

BD: Do you immediately make lots of xeroxes and send them to the Lutenists' Society of the World?

PO'D:

Well, there is some of that, although, if one discovers a manuscript or

print with a lot of important new repertoire, one wants to have the

opportunity

to perform it oneself before making it available to everybody else.

PO'D:

Well, there is some of that, although, if one discovers a manuscript or

print with a lot of important new repertoire, one wants to have the

opportunity

to perform it oneself before making it available to everybody else.

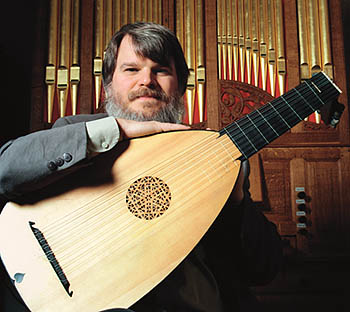

[Photo at right: With soprano Ellen Hargis]

BD: It's your discovery.

PO'D: There's a certain excitement in that. There's at least as much Sherlock Holmes involved in finding early music as there is in actually sitting down and playing it.

BD: Did the lutenists of the early times know about the music of other lutenists of the same age?

PO'D: Some of them did and some of them didn't. There were those who were quite widely traveled. Dowland, for instance, traveled all over Europe and was well acquainted with the best German, French, and Italian lutenists of the period. There were others who were real homebodies and tended to stay in their town and were quite well known in their area but didn't travel much. Their knowledge of foreign music was limited to whatever other traveling lutenists happened to have brought with them.

BD: Does that mean that each individual, or perhaps certain little groups, arrived at the same kinds of conclusions and ideas individually and separately from everyone else?

PO'D: No, I think there was an enormous amount of variety of approaches and attitudes, not only in the technique of playing as well as the interpretations, but also the kinds of sounds, and the aesthetics which each player developed. There was much more individuality than exists in today's classical music world. I'm sure that a lot of listeners are aware that 20 or 25 years ago, if you turned on the radio and heard a violin concerto being played, you could generally tell within the first few bars who the violinist was, as well as the conductor and the orchestra. I've heard a number of modern violin professors complaining that that's no longer possible because of this generic international style, and if they turn on the radio in the middle of a violin concerto, they can't tell who the violinist is because the top 20 players all sound very much alike.

BD: So we've lost the individuality.

PO'D: I think we've lost a lot of individuality because of increased travel, because of recordings, and being able to listen over and over and over again to a lot of different players, and the greater tendency to imitate. Players from Korea, France, Australia, England, all over the world, can be heard all the time now. And the competitions, in which there's a certain - unstated - but a certain style of playing which is preferred by juries, that promotes a kind of "one-style-fits-all" approach to making music.

BD: So rather than trying to be a great violinist in his or her own right, they want to try and be as close as possible to what the jury is expecting.

PO'D: There is certainly a lot of pressure on students to go in that direction. I frequently have this discussion with students about finding their own voice and developing their own individual style, not developing this horrible tendency that exists today of an interpretation which is essentially a patchwork quilt of the favorite ways of playing one phrase or one movement, based on listening to 20 different recordings of the same piece. Find your own way. Do it your own way. Don't try to imitate other people.

BD: Are you being successful in this quest?

PO'D: The immediate response is, "But what happens when I go to the competition? If I play in a radically different way, how will the jury react? Is it in my best interest - my best career interest - to play in a way that will please the jury so that I win the competition, or is it in my best interest, in the long term, to develop my own voice, and not to worry about what the juries think?" That's a very difficult decision. It's a difficult position to put young musicians in, and I think that we're going to have to look long and hard at the question of what juries are looking for, and what is deemed acceptable, and try to break out of this one-size-fits-all international style. It comes back to this belief that the critics love talking about "the definitive performance" of piece X, or Y, or Z. Can there be a definitive performance of a piece of art, a definitive interpretation of a piece of art? Does one have to choose the best painting of the Crucifixion of the 16th century? Does one have to choose between Raphael, Giorgione, Titian, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera, or can one not take all of them on their own terms and appreciate the differences, rather than to have to say, "This is the definitive performance of this piece."

BD: Are you taking matters into your own hands by going to the juries and shaking them up a little bit, and trying to say, "No, you must not mold these people"?

PO'D: [Without hesitation] If I'm on the jury, then I certainly push as hard as possible for allowing people who have very creative and individual approaches from not being criticized or having their performances given less credit than somebody who plays in the internationally-approved style. I think of this wonderful example of the Beethoven symphonies being played for decades and decades in tempos that have nothing whatsoever to do with Beethoven's own markings. There was a study done in Soundings magazine a number of years ago about this, comparing the original metronome markings of the string quartets and piano sonatas and the symphonies, with Beethoven's own markings. They found that most of the modern performances all fit within one very, very narrow band, usually having little to do with the original markings. Now what would happen, in that case, to a student who was really interested in finding out what the music is all about; a conducting student, or a pianist, trying to start from the original markings and find out what Beethoven might have meant with this?

BD: Isn't this partly to do with the instruments? I remember hearing a Beethoven symphony played by a so-called original instrument orchestra, and the tempos were erratic, but because it was the different instruments, they worked. Then I went back and realized that was what Beethoven called for.

PO'D: That's true. That's one of the problems, and perhaps one of the reasons that a lot of people have simply discounted the original markings. One of the things modern instruments don't do very well is speak quickly. They make a lot of sound, but they are not swift and agile compared to earlier instruments, and that has a lot to do with it. The reason I brought this up as an example is that it shows the kind of sheep-like quality of the modern classical musical life, that...

BD: Do period-instrument orchestras and copies of old lutes negate some of those problems?

PO'D: I think that what the original instrument movement is teaching us, and I hope that it will be the ultimate legacy, is to reveal more about what the composer originally had in mind, which may not always be realizable on a different instrument. I would never criticize anyone for playing lute music on the classical guitar, or the piano, or the saxophone because if it's good music, it should be played on any instrument available - which is how Renaissance and Baroque musicians approached their music. That's why Bach reused the same music, and arranged it for different instruments. One thinks of the Fifth Cello Suite in the arrangement for lute, or the A minor Violin Sonata in Bach's own arrangement for the harpsichord. So there's no problem with playing it on a different instrument.

BD: There's nothing more different than a plucked harpsichord and a bowed violin. [Chuckles]

PO'D: Right. And I think what one has to try to learn is how each instrument responds and how the music has to be changed in order to suit the new instrument. I'm not sure that it's possible for a modern symphony orchestra to play the Beethoven symphonies convincingly at his metronome markings. They are too fast for a modern orchestra. They were designed for a smaller orchestra of instruments that speak much faster and are much more transparent in timbre. So it was more natural. But what we can learn by hearing it done with the original instruments is what the intended effect might have been, as opposed to what we've just fallen into the rut of always playing and not even thinking about what other possibilities might be. You might not be able to play at exactly the same tempo or with exactly the same character, but one will certainly learn a lot from having tried to do it, or listening to other people who have done that.

BD: So are you putting forth the theory that neither is better. They should both exist side by side.

PO'D: I think they can exist side by side. I think they have to, otherwise the problem will soon be that it will only be possible to play music on precisely the instrument available at that time, which means that if you're a wind player and you want to play the music from Bach to today, you'll have to have 47 different oboes and learn 47 different techniques, and be able to make different kinds of reeds, and so on. One reaches a limit in terms of practicality. My own solution to the problem is that I have chosen to specialize in the music that I'm particularly interested in. I don't take the attitude that I have to play everything. I'm perfectly happy to listen to other people play the 19th century classical guitar repertoire, which I used to play as a guitarist, and still love dearly. But I'm perfectly happy to allow other people to play that repertoire well, and I'll concentrate on an area which is large enough to satisfy my curiosity, but small enough that I can still manage to play all of the instruments that were used to play that repertoire. I think that what will develop over the next 10 or 15 years is people who increasingly specialize in a small area of the repertoire, on exactly the right instruments, using as much information about the original performance practices as possible in order to play it and really bring it to life. There will be others who will play more generically on one or two instruments, and try to learn as much as possible about each repertoire, making compromises where they have to be made, in order to suit the different instrument that they're playing.

BD: Should there be sharing of information between these two groups of individual performers?

PO'D: [Without hesitation] Oh, absolutely. I would hope so. What I reject categorically is an attitude, which is fortunately less prevalent now than it 10 or 15 years ago, that "We're going to play it the way we've always played it, and we're going to play it in this way no matter what was originally done." You cannot have it both ways. You cannot say, "Mozart was a brilliant composer, but the players he wrote for were total incompetents; therefore we can ignore everything they did and play it the way we want to." Today, this arrogant attitude that "If they could only hear the way we do it today, they would be delighted," is such a complete red herring, because it necessitates a leap of aesthetics which anyone who knows about the aesthetics of the period in which a given repertoire was composed, knows can't possibly have existed.

BD: "Damn the critics and full speed ahead!"

PO'D: It's a question of aesthetics. One has to learn enough about the taste of a period in order to be able to understand how they wrote their music and what they were trying to say with it.

BD: Okay, then the big sociological question becomes... You try to understand the aesthetics of the period, and the instruments of the period. How can that translate directly or indirectly to performers and audiences - especially audiences - who have lived through a couple of world wars and depressions, and all of this? Do we just have too much collective memory?

PO'D: I think that that varies from person to person. There will always be people who will respond more to what's familiar and to what they've grown up with, and there will also be another half of society that will respond more to something new, something provocative, something different.

BD: But we've just simply lived through so much stuff. Our ears are going to hear the same aesthetic in a different way. Is it your responsibility, as the performer, to alter that at all, or is it our responsibility, as audience, to try and sift back through the ages?

PO'D: I think it's our responsibility, as performers interested in historical performance practices, to present the music in such a way that the audiences appreciate it, whether they completely understand what it is we're trying to do or not. I can enjoy excellent Thai cuisine without necessarily understanding very much about the culture of Thailand. It doesn't have to taste like Midwestern American cuisine for me to appreciate it.

BD: But you don't expect someone who doesn't like Thai cuisine to smear it with ketchup in order to enjoy it?

PO'D: No. By trying to play the music of the 18th century in the style of the 1990s rarely reveals very much about the music.

BD: Does it surprise you at all that there seems to be a large group of audience members that enjoys the old music and the new music but leaves this tremendous hole in the Romantic repertoire?

PO'D: I think that's true because there are a lot of similarities. A lot of the techniques required, both for singing as well as playing 20th century music, are quite similar to what was used in earlier periods. For instance, the use of vibrato ornamentally, and the use of a great variety of different timbres and types of articulations, as opposed to the 19th century ideal of the big, full, rich, powerful sound, played ultra-legato for long, sweeping phrases. That's a completely different aesthetic from the aesthetic of much contemporary music, as well as much Renaissance and Baroque music.

BD: So neither is wrong; they both should exist again side by side.

PO'D: Absolutely.

BD: Are we getting too many side by side by side by side by side by side?

PO'D: You can tell that I love various cuisines, but I think that it's quite similar in that the more variety we have available to us, we can choose whether we want to go to the same Northern Italian restaurant every night, or whether we want to go to a different restaurant serving other cuisines every night. I think that the two should peacefully coexist because there will be people who will want to always have something in a certain style. They'll always want to listen to 19th century Italian opera, and that's what really speaks to them, and they have no interest whatsoever in Baroque music, or 20th century music. They're really only interested in 19th century repertoire. And there will be others who will have more eclectic tastes, and will want to listen to music of all different periods played in a variety of different ways.

BD: Perhaps a dangerous question... Should restaurants with various cuisines exist side by side with the fast food chains?

PO'D: [Thinks for a moment, then answers in a low, gravely voice, as if to imply that such a prospect is out of the question] No.

BD: [Laughs]

PO'D: I think that one of the great failings of the 20th century is "fast and cheap" as opposed to "quality is everything." Quality and depth, and that's really what the arts are all about.

* * * * *

BD: Are you at the point in your career now that you expect to be at this time?

PO'D: [Thinks for a moment] I guess I'd never had any expectations when I went into music professionally, except that I knew that I was fascinated by Renaissance and Baroque music, and that that's what I wanted to do. But I really had no expectations as to the commercial viability of it. I think that had I grown up in a time in which there was no possibility to professionally perform this repertoire, then I would've found something else to do professionally, and I would've continued research and performance into this music on the side. I had no commercial designs whatsoever when I went into this music. It was just what I loved, and I've been extremely fortunate that all of this took place at a time in which there was increased public awareness and interest on the part of recording companies in making this repertoire available. I've been fortunate to have had quite a busy and successful career in doing what I love.

BD: Here's something that I ask modern instrument players, but is an equally valid question for an old instrument player: do you play the same in the recording studio as you do in the concert hall?

PO'D: No. With the lute it's impossible because there are so many sources of mechanical noises that just result from changing position on the lute, which are virtually unavoidable. Someone sitting ten feet away would never hear them, but a microphone not only picks them up but amplifies them. So when I record, I spend, unfortunately, a lot of my energy and attention on developing specialized techniques for avoiding making various sounds which are really quite unpleasant when recorded by very sensitive microphones that I don't have to bother with at all in performance.

BD: Is it too much of a bother to make records, then?

PO'D: Well, I wish there was some way of being able to play in the way that you would for a live performance, and make that come across on recordings.

BD: You can't just stick the microphone 15 feet away and hope for the best?

PO'D:

I've done a lot of experimentation with different kinds of

microphones.

In a way, I almost think that the microphones of the '50s were

preferable

for a lot of this repertoire because they were not so sensitive on the

high end. They were closer to the sensitivity of the human ears.

PO'D:

I've done a lot of experimentation with different kinds of

microphones.

In a way, I almost think that the microphones of the '50s were

preferable

for a lot of this repertoire because they were not so sensitive on the

high end. They were closer to the sensitivity of the human ears.

BD: One single bi-directional microphone hung about 20 feet above, and that's it.

PO'D: That's right, exactly. But try convincing a modern recording company to agree to that.

BD: That's heresy! [Laughter all around] Well, despite all of that, are you pleased with the records that you have made over the years?

PO'D: [Ambivalently] I'm never satisfied with what I do. I think that every musician, every artist, every performer, every athlete feels that they always come up short. I find it painful to have to listen to recordings of mine too near the time that I recorded them, where I can still remember all of the passages, and what I was trying to do with them. But I find that a few years later I can really sit down and enjoy them, and say, "Ooh, that really was quite nice." I didn't have that feeling at the time because I was searching for something more; I was searching for something else that I wasn't able to realize. But I've started to take a more philosophical attitude towards recording now, that rather than falling into the trap of trying to create my definitive performance, I view it more as a photograph: "This is what I did on this day, and tomorrow I would do something different." And it really is just a snapshot, a moment in time. I think that makes recording really much more interesting. An awful lot of recordings are, frankly, boring, because performers are trying desperately to get every single thing right, to have every note be in its place. This sort of clinical perfection is often so sterile as a result. One listens to recordings of, say, Schnabel playing Beethoven, and, yes, he misses a lot of notes, and there are various technical problems, but he has more to say about that repertoire than any modern pianist that I know of. And the impact is so strong. It's, in a way, like speaking. There can be grammatical mistakes along the way, but what's really important is the communication and what you have to say. What's happened in the modern recording industry is we're interested in this clinical perfection rather than the impact that it has.

BD: You would rather have "caught" snapshots rather than "posed" snapshots?

PO'D: I think that would be preferable.

BD: Many of the major conductors are now doing recordings in concert after having spent years and years in the studio.

PO'D:

I think that's a very good trend, and the only thing I would say is

that

we have to try to prepare audiences for the fact that there are going

to

be some imperfections. After decades of listening to

overly-edited

recordings, where, in the space of two and a half or three minutes,

somebody

like Glenn Gould would use 88 splices to make everything note-perfect,

people should be willing to sacrifice this kind of clinical cleanliness

for a spirit and spontaneity and character which is really lacking in a

lot of modern performances. The other thing is that after I've

worked

on a repertoire for recording, and spent days in the recording studio

playing

it in that way, I find that when I perform it, it's lost an awful lot

of

character that it used to have when I didn't care about the microphone,

and about every tiny note, and whether there was a squeak or a buzz, or

whatever. I would rather catch the spontaneity of the moment and

try to communicate something to the audience. We've developed a

generation

of performers who have spent most of their time in the recording studio

and take that same kind of approach when they're in front of an

audience.

No wonder it's so boring in concert. Whereas in the good old

days...

I sound like an old person, but I'm sure that a lot of the older

listeners

will agree with me that before the days of thousands of recordings

being

available in perfect acoustical environments, with every note spliced

together

out of a dozen different takes of the same piece, that there was an

excitement

in the performances that's very often lacking today. We marvel at

the perfection and the accuracy of performances. What I hear

people

remarking on when they come out of a concert is, "Wow, that person has

outstanding technique; everything was so clean and so clear," or,

"Listen

to those brilliantly produced high notes," or "...how much power and

volume

they were able to create."

PO'D:

I think that's a very good trend, and the only thing I would say is

that

we have to try to prepare audiences for the fact that there are going

to

be some imperfections. After decades of listening to

overly-edited

recordings, where, in the space of two and a half or three minutes,

somebody

like Glenn Gould would use 88 splices to make everything note-perfect,

people should be willing to sacrifice this kind of clinical cleanliness

for a spirit and spontaneity and character which is really lacking in a

lot of modern performances. The other thing is that after I've

worked

on a repertoire for recording, and spent days in the recording studio

playing

it in that way, I find that when I perform it, it's lost an awful lot

of

character that it used to have when I didn't care about the microphone,

and about every tiny note, and whether there was a squeak or a buzz, or

whatever. I would rather catch the spontaneity of the moment and

try to communicate something to the audience. We've developed a

generation

of performers who have spent most of their time in the recording studio

and take that same kind of approach when they're in front of an

audience.

No wonder it's so boring in concert. Whereas in the good old

days...

I sound like an old person, but I'm sure that a lot of the older

listeners

will agree with me that before the days of thousands of recordings

being

available in perfect acoustical environments, with every note spliced

together

out of a dozen different takes of the same piece, that there was an

excitement

in the performances that's very often lacking today. We marvel at

the perfection and the accuracy of performances. What I hear

people

remarking on when they come out of a concert is, "Wow, that person has

outstanding technique; everything was so clean and so clear," or,

"Listen

to those brilliantly produced high notes," or "...how much power and

volume

they were able to create."

BD: So they're truly missing the forest for the trees.

PO'D: Exactly. How many times have people come out of a concert performance today, and said, "I was reduced to tears three times during the concert," or, "I went through a wide variety of emotions at the concert; I laughed out loud at one moment; I became so angry and furious at another moment that it was all I could do avoid to avoid bashing my neighbor in the head, and I cried at another point." These are exactly the reactions that are reported to have taken place during performances throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. The people were so moved by the performances that those were their reactions, and to the people of that time, that was what music was about.

BD: Is there any way to get back to the idea that music is a participatory sport?

PO'D: I think we have to seriously rethink the whole concert experience. I think the idea of performing in large, dark concert halls, watching performers wearing Victorian eveningwear, only politely acknowledging the presence of the audience in the form of a polite bow at the beginning and end of the evening, is so foreign to the way most people would like to be entertained, and would like to be able to respond. Think of a performance at a jazz club where the saxophonist gives a wonderful solo, and you spontaneously shout, with the other members of the audience, your appreciation, much as happened in Elizabethan theater performances of Shakespeare. We're suppressing that by making people sit in large, dark concert halls like stones, and politely clap their hands together at the end of a performance in a way takes all of the spontaneity out of the audience. It's certainly long since gone from the performers because they've been trained to play everything note-perfectly, over and over and over again, to wear their Victorian eveningwear, to politely bow at the audience at the beginning... There's no communication. When I first became interested in the lute, I went to a couple of Julian Bream recitals, and just the fact that he would talk to the audience - explain what the instrument was, say something about the life of the composers, about the pieces he was going to play - it was so much more interesting than going to piano recitals by excellent pianists, but I was so bored because there was no contact with the audience; there's no rapport.

BD: Should we go back to the idea of playing an Elgar symphony or a Tchaikovsky symphony in a darkened hall, but then leave everything else be as you've been talking about in the last few minutes?

PO'D: [Thinks for a moment] That's a good question! Without dodging it, I would say that the one thing that I most fear about the scenario, even 20 years from now, is whether we will have live performances, with live audiences attending, or whether with all of the talk about computer, television, telephone being combined, whether there won't be an awful lot of broadcast live performances.

BD: So we are really retreating into our caves more than we think!

PO'D: I fear. I would love to see the concert experience made as exciting as it once was. If you ask sports fans would they rather sit and watch something on television or be there, would you rather go to a Bulls playoff game or sit at home, the people who really know and understand would say, "Well, of course I'd rather be there. There's such electricity in the air; you can actually see and feel the power of these people, being much closer to them, that you can't capture by television." And it's exactly the same thing, I think, in live performance. However, because we have cultivated this manner of performance, with no communication between the performer and the audience. The audiences feel they have to sit quietly in darkness, and they'd better not consider applauding in between movements, even if a performance of a movement was hilariously funny, and what they really want to do is to start laughing for a minute or so before the next movement comes, or for people to leap out of their seats and react after an exciting movement even if it happens to be in the middle of a sonata or a symphony or a suite. Why should people have to sit there like bumps on logs and not respond? Because in the late 19th century that was how they were trained to respond.

BD: Right. If I'm listening to a Mozart symphony, he'll throw in a joke and I'll find myself giggling, and I'm a little self-conscious because I'm the only one in a large section that's giggling. [Chuckles]

PO'D: I remember giving a concert in London about 13 or 14 years ago, where I played a battle piece on the archlute. When I got to the end with the final cannon shot, and I turned this six-foot long neck towards the audience, delayed the last chord, and then shot them with this cannon shot. The audience spontaneously started laughing and enjoying themselves, but then they suddenly caught themselves and realized, "No, we're English classical concert audience members; we don't do this." And they started looking around to see who was responding in that way, and they immediately stiffened up and started politely applauding. I thought, "What a sad commentary." People, if they're allowed, to respond spontaneously, will enjoy themselves.

BD: I would think that would almost be a victory because you got 'em for a minute!

PO'D: There was a split-second of wonderful response from the audience, followed by this incredibly repressed, typical response of classical music audiences.

BD: So you want them literally to let their hair down.

PO'D: Exactly! I think we have to as performers;

I think they have to as audience members. Otherwise, as we watch

the audiences for classical music grow older and older and smaller and

smaller, I tell my students that there's a more important issue of

performance

practice: whether there are going to be any jobs in classical

music

when you graduate from the Eastman School of Music. We can't take

that for granted. What we're now doing is competing for

entertainment

dollars. So, to the man or woman working at an office from nine

to

five, you are posing the following scenario. Would they like to,

A) stay downtown, go out to dinner in an expensive restaurant, pay more for parking, or have to go to a new place for parking, pay a babysitter, pay a lot of money for tickets to sit in the back of large, dark auditoriums where the performers politely bow at them at the beginning and end of the performance, but no more real communication than that, you finish the performance quite late, walk around not always the safest part of large metropolitan areas to go back to your car, drive home to get home very late in order to wake up early the next morning to go to work, with a fairly steep price tag; or,

B) offer this same person (who, remember, has worked in the office from nine to five) to pick up a video or two, or maybe a more cultured person would stop at the CD store and buy a couple of CDs, drive home, change into their bathrobe, or whatever they want to wear, be able to lounge around in the privacy of their own home, order a pizza to be delivered, and watch the video, or listen to their CDs for a total price, maybe $25?

BD: Does that shake 'em up?

PO'D: They get very upset. [speaking vehemently] "How can you possibly compare these two? They're not comparable!" I say, "They are comparable. People are making those choices every single day."

BD: Well, comparable or not, those are the decisions that people are making.

PO'D:

Right. And the students always say, "Well, what can you

do?"

And I say, "I don't think there's any one answer." But what we

better

be thinking about, as performers of classical music, or people who love

classical music, is to try to figure out a way to make the concert

experience

so exciting, so interesting, that people do not have to make that

choice.

If you have a truly electrifying performer playing very interesting

repertoire,

communicating maybe a pre-concert lecture, maybe even talking to the

audience

during the piece about what to listen to, or something about the

composer,

or even humorous anecdotes, you can then make that concert experience

so

interesting and vital and spontaneous, that people will say, "Well, of

course my CDs can't possibly compare to that. I'm going to stay

downtown

and go to the concert."

PO'D:

Right. And the students always say, "Well, what can you

do?"

And I say, "I don't think there's any one answer." But what we

better

be thinking about, as performers of classical music, or people who love

classical music, is to try to figure out a way to make the concert

experience

so exciting, so interesting, that people do not have to make that

choice.

If you have a truly electrifying performer playing very interesting

repertoire,

communicating maybe a pre-concert lecture, maybe even talking to the

audience

during the piece about what to listen to, or something about the

composer,

or even humorous anecdotes, you can then make that concert experience

so

interesting and vital and spontaneous, that people will say, "Well, of

course my CDs can't possibly compare to that. I'm going to stay

downtown

and go to the concert."

BD: It is interesting to know that you, who have fought this battle just in the music, are now fighting it in the presentation of all musics. Bringing Renaissance music to the modern-day audience, you're fighting this battle you were just talking about, just to bring the music. Now you're fighting the battle with all concert music.

PO'D: I think it all goes together. What interests me about Renaissance and Baroque music is that they were such creative, inventive people, always searching to make music a more powerful experience.

BD: We've been kind of dancing around this, so let me hit you with the great big question: what's the purpose of music?

PO'D: I think that there isn't one answer that fits all kinds of music. If we talk about that question in 17th century terms, there was an Italian answer and a French answer. The Italian answer, which is certainly more to my own taste and my own attitude about it, is that music is to express the various emotions of the human condition, and to, if you will, manipulate the emotions of the listener, to make them go through the emotional wringer. The French would say, "The function of music is to tickle the ear." It should be pleasing, it should be always sweet and beautiful and lovely, and graceful and elegant;...

BD: Unchallenging?

PO'D: Exactly. That is what the Italians said, in the Baroque, about French Baroque music. They said, "It's too boring, because they always make a pretty sound, the melodies are always lovely and elegant, and there's no variety in it. Everything is a moderate tempo, a moderate dynamic, and it's always beautiful." Which is really, in a way, what new age music is.

BD: I was going to ask if they were they misplaced out of the 20th century.

PO'D: Exactly. It's very similar. And I know a lot of classical radio stations in this country, have been told by various consultants to stay away from anything provocative or controversial. Just play middle-of-the-road performances of familiar pieces, because there is a large segment out there who would prefer not to be challenged. They simply want to have a constant stream of pretty sound going on, that makes them feel good and doesn't challenge them.

BD: I'm glad to say that our station [WNIB, Classical 97] has, for the most part, rejected that as much as possible. We don't play just Vivaldi.

PO'D: The interesting thing about earlier repertoires is, because both of those attitudes coexisted, one has the opportunity even on a single program to play one half of Italian music, with very demonstrative, dramatic, a lot of dynamic contrast, a lot of timbral contrast and tempo variety; some shocking, dissonant, harsh chords, followed by beautifully sweet harmonies as well, and at the same time, on the same program, play French music, with this constant stream of pretty, lyrical melodies and sweet tone.

BD: So then how do you divide it? Do you play the easy stuff and the pretty stuff first, to lure them in, and then hit them with the Italian, or do you play the Italian and then give them a rest with the French?

PO'D: I think it depends on the audience I've experimented with different types of programming to enable both approaches, even sometimes on the same program. I might start the beginning of the program with something French, and then come back at them with the Italian, and then start the second half with something dramatic and shocking, and then end with something more soothing. Or the reverse. I don't think that one way is better than the other. They're just different.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of old music?

PO'D: [Thinks for a moment, then answers with certitude] Yes. I am, because I think that there is still an enormous amount of unknown repertoire of very high quality, and I think that there are more and more talented performers who are willing to come to grips with all of the problems involved in playing it, who are playing better and better all the time. I think no one would deny that performances on original instruments now are far better than they were 15 years ago. A lot of the staunchest opponents to playing on original instruments 15 years ago - because they said it was scratchy, or it was out of tune, or the players weren't very good - are now fans.

BD: Well, you've negated their criticism.

PO'D: Right. Right. And now we have a lot of major modern players and conductors who frequently conduct original instrument ensembles, or play themselves. My friend Jeff Kahane, the pianist, played fortepiano in a Mozart piano concerto last year with Chris Hogwood in Boston. I really admire the courage of a very successful modern pianist to stick his neck out, try to learn how to play a rather different instrument than he's used to, in the interest of exploring the music. Simon Rattle has often conducted the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, in London, an original instrument orchestra, and he loves it! He says he learns so much from working with these players and the instruments, and learning about the balance, and the articulation, and the timbre, and the color possibilities of the instruments.

BD: But then, of course, he takes that back to Birmingham and uses that in his big orchestra!

PO'D: That's right.

BD: Does he bring something of the big orchestra back to the early instrument orchestra?

PO'D: I think that there's a lot that we can learn from each other. Rather than saying, "One side is good, the other side is bad," which is the way things started out 20 years ago, this adversarial relationship, is now much more a question of give-and-take.

BD: Would it be anachronistic to have the older instrument consort learning from the newer one since it hadn't happened yet when the music was being played for the first time?

PO'D: I think it's not so much a question of learning about something that hadn't happened yet, as it is in this case, of Simon Rattle, an outstanding modern conductor with a lot of experience conducting a wide variety of music, who has more expertise as a conductor than a lot of the early music practitioners who became conductors almost by default, because they were harpsichordists or violinists, or in some cases singers, who felt a need to work with larger ensembles and re-evaluate this repertoire, but weren't trained as conductors and came at it very late in life. It makes a lot of difference, and my colleagues in the various Baroque orchestras in London have said it was so revelatory to work with Simon, because he's such an outstanding conductor and knows exactly what he's doing.

* * * * *

BD: Let me ask perhaps an outrageous question: should modern composers compose for Renaissance instruments?

PO'D:

I think they can! I think it's certainly a possibility. It

provides timbres that otherwise aren't available.

PO'D:

I think they can! I think it's certainly a possibility. It

provides timbres that otherwise aren't available.

BD: If Henze wrote a concerto for theorbo, would you do it?

PO'D: Sure! I haven't spent a lot of time trying to encourage modern composers to write or the lute, because there's so much old music for the lute that I'll never have a chance to study and play all of it. I've been preoccupied with that repertoire, but certainly, if a great modern composer wrote a piece for me, I'd be delighted to play it. And, of course, the lute, or the theorbo, or the recorder, or the harpsichord, or the viola da gamba have a lot of different possibilities that their modern counterparts don't have.

BD: There are some modern concertos for harpsichord and recorder, so maybe the next one should be the lute.

PO'D: The lute or the viola da gamba.

BD: You like playing Renaissance music, though.

PO'D: I adore Renaissance music. I was in Italy in the summer, in Mantova and Ferrara, the two great Italian Renaissance cities that I hadn't been to before, and I suddenly realized, looking at the paintings and the architecture, and thinking about the music that I love so much, that this was the pinnacle of human achievement.

BD: You mean we've gone downhill since then?

PO'D: I don't think that there has been another time that I am aware of in which all of the arts were flourishing on such a high level. Just imagining what it was like in a time with Francesco da Milano playing the lute with Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo and Ariosto and Bembo all around at the same time. It must've been an extraordinary experience to have been around that much genius and creative artistry all in one period.

BD: We're not just adding to it a little bit with our hindsight?

PO'D: Well, I think that this is not to invalidate in any way any other period, because there have certainly been other periods of great musical genius, great artistic genius, great literary genius. But I don't know another time when they were all operating on such a high level simultaneously and inspiring each other in that same way. That's what I find so fascinating about this period. In order to understand the music I have to spend a lot of time studying the literature and reading Guarini and Tasso and Ariosto, and Shakespeare, and studying the art history and the cultural history. It's just such a great privilege to be able to study such genius in so many fields all at once.

BD: You're a true Renaissance man! Thank you for bringing your artistry to Chicago. I'm very glad that you've been here, and hope you will return often.

PO'D: I hope so. It's a pleasure to be here.

===== ===== ===== ===== =====

--- --- --- --- ---

===== ===== ===== ===== =====

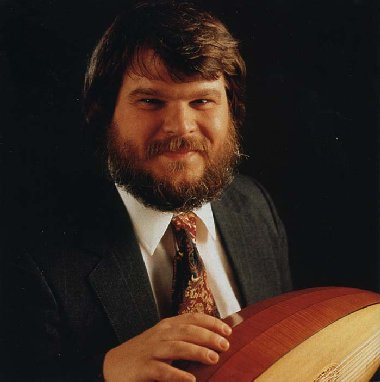

|

PAUL O'DETTE

Paul O'Dette has performed at major international festivals all over the world, including Boston, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Berkeley, Utrecht, London, Bath, Paris, Montpellier, Bremen, Dresden, Munich, Berlin, Frankfurt, Leipzig, Vienna, Prague, Milan, Geneva, Barcelona, Copenhagen, Oslo and Melbourne. Though best known for his recitals and recordings of virtuoso solo lute music, Paul O'Dette maintains an active career as an ensemble musician as well, performing with such artists as Jordi Savall, Gustav Leonhardt, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, William Christie, Christopher Hogwood, Andrew Parrott, Nicholas McGegan, Tafelmusik, The Parley of Instruments and The Harp Consort. He is also a member of Tragicomedia, a continuo ensemble acclaimed for its recordings and concerts of 17th-century operas, cantatas, and oratorios. To date, Paul has made more than 100 recordings, many of which have been nominated for Gramophone's 'Record of the Year' Award. He has also broadcast for the ABC (Australia), BBC (United Kingdom), CBC (Canada), Radio France, RAI (Italy), Westdeutscher Rundfunk (Cologne), Bayerischer Rundfunk (Munich), SFB (Berlin), NOS (Holland), Austrian Radio, Spanish Radio and Television, TV Ankara, Hungarian Television, Norwegian Radio, Danish Radio and Television, Swedish Television, Swiss Radio and Television, National Public Radio (USA) and CBS Television (USA). Recently Mr O'Dette has been active conducting Baroque operas. In 1997, together with Stephen Stubbs, he led performances of Luigi Rossi's L'Orfeo at Tanglewood, the Boston Early Music Festival and the Drottningholm Court Theatre in Sweden, while in 1999 they directed performances of Cavalli's Ercole Amante at the Boston Early Music Festival, Tanglewood, and the Utrecht Early Music Festival and Provenzale's La Stellidaura Vendicata at the Vadstena Academy in Sweden. The 2000/01 season included productions of Monteverdi's Orfeo for the Vancouver Festival and Lully's Thesee for the Boston Early Music Festival. In addition to his activities as a performer, Paul O'Dette is an avid researcher, having worked extensively on the performance and sources of 17-century Italian and English solo song, continuo practices and lute technique, the latter resulting in a book co-authored by Patrick O'Brien. He has published numerous articles on issues of historical performance practice and co-authored the Dowland entry in the forthcoming update of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Paul O'Dette has served as Director of Early Music at the

Eastman School

of Music since 1976 and is Artistic Director of the Boston Early Music

Festival.

|

© 1993 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on October 5, 1993.

Portions

were used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1994 and 1999. This

transcription was made early in 2007 and posted on this website at that

time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.