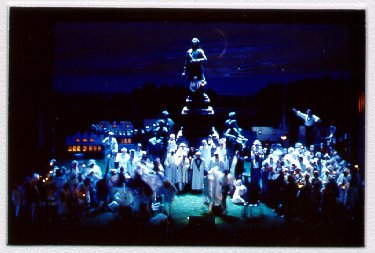

Die Meistersinger (Act 2) - Lyric Opera of Chicago

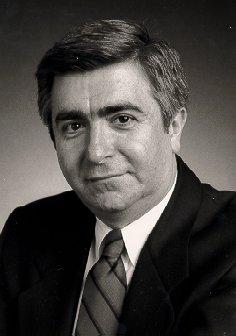

Donald Palumbo is the Chorus Master for Lyric Opera of Chicago. Originally from Rochester, New York, he got involved with choral music when a little company in Providence, Rhode Island, asked him to prepare a small chorus. He'd been playing piano for rehearsals and also conducted a few orchestral sessions. When the Dallas Opera needed an assistant to the legendary Roberto Benaglio, who had been the Chorus Master for La Scala, Palumbo got to work with him and saw how important the role of the Chorus Master is and how the massed vocal ensemble can contribute to the musical shape of an opera. He was, as he told me, "In the right place at the right time. It's a profession without many members, but I'm certainly thrilled to be with Lyric Opera." He is aware of the great tradition of fine choruses in this city, and knows he must live up to the legendary Margaret Hillis, who founded the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957 for Fritz Reiner, and remained its director until her retirement in 1994. "Here in Chicago," Palumbo notes, "the role of the chorus is recognized, and we're given the prominence that we deserve."

In Europe, his engagements have included the Aix-en-Provence Festival, Opéra de Lyon, and the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, as well as preparing Britten's War Requiem with the chorus of Radio France. In 1999, he was appointed Chorus Director of the Salzburg Festival, the first American to be named to that position. He is also the Chorus Consultant to the Canadian Opera Company, and was Chorus Master for the Opera Theater of St. Louis.

During his decade in the Windy City, Palumbo has overseen the choral

efforts for many standard works as well as the new creations which are

part of Lyric's ongoing commitment to the living American composer.

I caught up with him a couple seasons back when he was preparing opera's

biggest choral work, namely Wagner's Die Meistersinger. So, our chat

included much about that massive opus.........

Bruce Duffie: Is Meistersinger just too big?

Donald Palumbo: No, it's not too big. It's just as big as it needs to be.

BD: Is Meistersinger the biggest thing that you have to do - not just this season, but any time?

DP: I think most chorus-directors consider Meistersinger one

of the biggest and most difficult. The problem is not just the numbers,

but also the number of different groups involved. The ‘Lehrbuben'

is a specific smaller group of 8 women and 8 men and their music is totally

different. You have this incredibly complicated end of the second

act with a group of women neighbors, and a group of tenor-and-bass neighbors,

and a group of bass ‘Meister', plus the ‘Lehrbuben,' plus the soloists,

plus the orchestra. Then in the third act, the chorus functions as

all the guilds of the town, plus the ‘Lehrbuben' again and the people of

the town. It's extremely complicated to put together. Many

of the lines are totally separate and independent, so it involves rehearsing

groups separately and then combining them and making sure no one gets thrown

off by hearing the other groups suddenly pop in after they've been rehearsing

on their own for awhile.

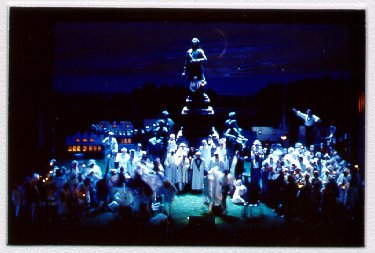

Die Meistersinger (Act 2) - Lyric Opera of Chicago

BD: Is it your responsibility to make sure that everybody knows exactly what they should do and then let the conductor shape it?

DP: Certainly. With Meistersinger I have to make sure all the ingredients are properly prepared. I'm sort of the sous chef. We get everything individually prepared and have some rehearsals where we put it all together, but in this piece, you never quite know what you're in for until you actually get onstage and do it in the spatial relationship. At first, that's just with piano, which is only part of the picture, and then you'll add the principals, which is another ingredient, and then you'll add the orchestra, which is the final sonic ingredient. It's an interesting process to start in August for something that you won't get to see exactly what it will be until the next February.

BD: Is it your responsibility to know what it should sound like?

DP: Definitely. It's one of those pieces where I encourage the choristers to try to listen to a recording so they get an idea of what it sounds like with orchestra. It's certainly very different than sitting in a room with a piano accompaniment. The orchestration is so rich and so wonderful. I think it's an opera that is important to have in your ear how this piece should sound.

BD: But they need to be careful not to get onstage and listen for the orchestration and get distracted!

DP: Most opera choruses are used to that problem. There's so much going on onstage, and they're pretty good about knowing that they can't get too distracted. The more complicated the piece, the more important it is. During Traviata, they can probably listen to the beautiful melodies coming out of the orchestra and not go too wrong. But there are many sections in Meistersinger where, if you don't block everything else out and keep your count going in your head, you can easily lose track and find it very hard to get back on.

BD: Is it easier or more difficult to do an opera that is unfamiliar, rather than one you do year after year after year?

DP: It's easier in one sense. The chorus comes with no pre-conceived notions of how the piece should go, so you can start rehearsing very simply with words, rhythms, and then notes. They don't ‘remember' that the last time they did it the conductor did a huge accelerando so they're used to speeding up at that point, and they weren't so far upstage that they had to sing louder even though it's marked piano in the score. When people have done productions before, they come with a lot of ideas from those previous times that they've sung the piece. On the other hand, it certainly is easier to rehearse Traviata, which the singers almost know when they come to the first rehearsal, as opposed to Meistersinger where the vast majority of them will be seeing the notes for the first time.

BD: Is it particularly difficult to do a Traviata where you have just a few newcomers and they have to catch up quickly?

DP: It may be more difficult for them, but no one's complained yet. We've had a few Traviata rehearsals this week and they've moved very quickly and they've been doing very well. I've been very pleased with it. I've noticed that the ones who were not with Lyric the last time we did it were more in their scores than some of the other people. But they don't seem to be particularly confused by the pace that we're moving at. You have to make sure that you're keeping the interest of the people who have sung this work a lot of times, so I try to immediately go for more of the nuances and expression and trust that the notes and words of the piece will come along for those who are less familiar with the piece. But I can't treat the first Traviata rehearsal in the same way I did the first one for Meistersinger. Any new work needs more teaching of text, diction, basic notes and rhythms.

BD: So you plan ahead and schedule more rehearsals for less-known works?

DP: Exactly. I do that for any big opera which has a lot of chorus music. Mefistofele this season is like that, but maybe half of our members did it with us just a few years ago.

BD: Do you rely on others in each section to help out the newbies?

DP: Definitely. I always try to tell new people to sit by someone who's been around or have done the piece before. It's easier to make sure the markings are consistent and it helps to have someone sitting next to you who's secure in the part.

BD: Do you audition all the singers yourself?

DP: We have a core group of 48 singers that is a permanent chorus, and they don't audition every year. There are operas that we can do with just that group - like Traviata - but every other opera this season involves supplementary choristers, and we audition a large number of singers each season. Most are from the Chicago area, but in the past few years, we've had people come in and audition from Denver, from Dallas, from New York, and a few of them have come here to do this work.

BD: Are these experienced choral singers?

DP: Some of them have had a good amount of experience in other opera companies. We're very lucky here to have a great pool of singers to draw from because we do rely heavily on supplementary choristers especially when we have several operas that need extra people.

BD: Who decides how many will be in the chorus of a particular opera?

DP: That's a consideration we make based on musical decisions. We confer with our Music Director, but not usually with each individual conductor. Once we've determined the number, which is usually done well in advance, we inform the conductor and make sure there is not a problem. The decision is also based on the production involved. If it's very intimate and the sets are smaller, that might determine how big a chorus can be used. There are costume considerations and financial considerations, of course, but primarily it's musical. We say we're going to do a certain opera and I say, "I'm thinking of this many choristers. Is this going to work in this production? Is this going to work in our budget?" We discuss it, and sometimes the numbers go up and sometimes they go down.

BD: Without being specific, has there ever been a problem with the number?

DP: No. We're very conscientious here of honoring the score and I don't think we've ever done something to compromise the numbers.

BD: Has the director ever asked for twice the number and that makes musical nonsense?

DP: No. Usually the directors want half the chorus so

they don't have to deal with a zillion people banging into each other onstage.

The directors are happier with smaller numbers of choristers. We

usually come to a meeting of the minds. We usually get everyone on.

The music generally wins out here. For example, in Traviata, the

first act is very expansive and

La Traviata (Act 1) - Lyric Opera of Chicago

fills the stage quite far upstage. When we first did it, we were going to try to have fewer numbers and we decided musically it wasn't a good idea so we put more people in at the last minute. We have to be flexible opera-by-opera and season-by-season. Tosca can involve many, many singers, but the way our production is, not many choristers would actually get onstage in the procession at the end of the first act. So it doesn't make much sense to engage a chorus of 80 for our Tosca. In another place, like Verona, for example, or anyplace where you have a huge expanse, you would want a large congregation singing the Te Deum. So we adjust.

BD: Does it make any difference to you in the musical preparation if there's 20 singers or 80 singers?

DP: Sure it does. You have to adjust how you phrase and where you breathe. This past year I did a Beethoven 9th, which is not an opera, but it's a choral piece and we did it with an operatic chorus. We had only 50 voices, and I don't think many symphony orchestras do that work with just 50 singers. That means you have 14 sopranos, so when they have to sustain a high A for an entire page, you can't let them take breaths wherever they want - which is what usually happens in a large group. You have to plan where each individual singer takes a breath. So the smaller the number, the more carefully you have to plan phrasing, breaths, articulation and things like that. Things that tend to get smoothed over with larger numbers become very obvious and clear with a smaller group. I find you have to be very careful how you prepare a smaller chorus.

BD: Did operatic composers throughout the ages really understand the chorus?

DP: I think some did. Verdi, in his way, certainly understood. Some of his male choruses are the essence of Italian Opera in the 1800s. I think the choruses in Meistersinger are just beautiful. Even in the brief choral sections in Götterdämmerung, Wagner knew why he wanted to have this huge horde of men invading the stage to create this sound which was just so primitive and so overwhelming. I think he had a great sense of how to use the chorus. Puccini was not as chorally-oriented as some of the other operatic composers, but in Madame Butterfly, they are used very sparingly to the most amazing effect. The humming chorus is magical and done with the simplest means. By Turandot, he must have realized he had all these people available and decided to write for them.

* * * * *

BD: What do you look for in a choral singer?

DP: I look for a good musician. I look for someone who is going to have a voice that will add to a massed sound. Some very pretty, light, lyric voices that would be wonderful in some solo roles might not be suited to being good choristers. They might be so light that they don't add to the sound. If we're going to engage a singer, it has to be because they're creating a component of a massed group of people.

BD: Is this something they can do anything about, or is it just what they have or don't have?

DP: Up to a point. Some people have voices that they use in an almost apologetic manner and don't want to really let go with all the sound they have. That's something you have to do in an audition. They have to analyze what they have. Is it something they can get more out of if they want more? Then we have to decide if this person is going to add and blend and function in the concept of the sound that I have in my head and with the people that I've already engaged. Auditioning for a chorus is a difficult procedure. We have to make judgments and it's not very clear-cut all of the time.

BD: Should someone who wants to sing solo roles ever get involved in a chorus?

DP: Oh of course! I never demand that people sing in

a way that is going to do any damage to their voice. I always want

good singing and many great singers have started out in a chorus.

It's a wonderful experience and a way to get your feet wet. You're

around great musicians. You're around the opera house. You

hear the operas and get some stage experience. I don't see anything

wrong with spending a couple years in the chorus to use as an apprenticeship.

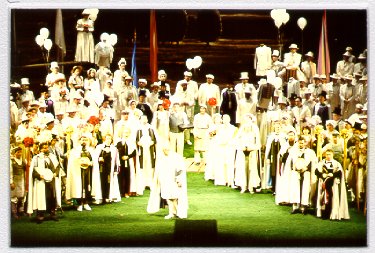

Die Meistersinger (Act 3) - Lyric Opera of Chicago

BD: Be real-life ‘Lehrbuben.'

DP: Exactly.

BD: If Meistersinger is perhaps the most difficult opera, what are some of the simplest?

DP: The standard Mozart operas have a minimal amount of chorus. Don Giovanni and Marriage of Figaro have some, but Idomeneo and Magic Flute have more, and it's quite satisfying - moreso than Così. Some of the Handel operas have very minimal chorus - just your basic four-part writing for soprano, alto, tenor, bass.

* * * * *

BD: When you prepare a chorus, you have to please the conductor. Do you also have the public in mind?

DP:

Definitely, but the conductor should have the public in mind as well.

For my taste, it's always the composer and the public. You want to

do justice to the composer by executing the score, and that means bringing

some sort of enjoyment and enlightenment to the public. So it's all

tied in. If you prepare a chorus with a dynamic range that is too

soft for the situation and the public can't hear them, you're not doing

your job properly. Dynamics is one of the crucial points that conductors

and chorus masters are always concerned about. If the public can't

clearly hear what they need to hear to be swept up in the opera, we're

not doing our jobs. If the orchestra is too loud - or too soft -

we're not doing our jobs.

DP:

Definitely, but the conductor should have the public in mind as well.

For my taste, it's always the composer and the public. You want to

do justice to the composer by executing the score, and that means bringing

some sort of enjoyment and enlightenment to the public. So it's all

tied in. If you prepare a chorus with a dynamic range that is too

soft for the situation and the public can't hear them, you're not doing

your job properly. Dynamics is one of the crucial points that conductors

and chorus masters are always concerned about. If the public can't

clearly hear what they need to hear to be swept up in the opera, we're

not doing our jobs. If the orchestra is too loud - or too soft -

we're not doing our jobs.

BD: You mentioned that Beethoven 9th. Do you do much work outside the opera house?

DP: I have in the past. I've done less recently. I sometimes go to the Canadian Opera Company after the season at Lyric is finished, and we've done the Verdi Requiem as well as that Beethoven 9th. It's fun to do those pieces with operatic choruses. First of all, they don't know the repertoire. You would think all choral singers would know those two works, but most of them had not ever sung those pieces.

BD: Is the Requiem Verdi's greatest opera?

DP: I've never felt that way. I think when he wrote for the stage, he knew he was writing for the stage and there are aspects of the music that only really work when you're onstage with costumes and lights and movement. I think that's tied in to his music. I would not want to see a staged-performance of the Requiem. The gestures are certainly operatic, but overall the great thing about opera is how many aspects are involved and how many of the arts are involved. We have set designers and costume designers and makeup personnel, we have wig people... It's endless all the aspects that go into opera! And Verdi was one of the great composers who was able to create these works that are epitomes of the art form.

BD: Does it ever surprise you that the whole thing comes together on the night of performance?

DP: Surprise isn't the word. You have this great trust that it's going to happen. You hope that you've done your job well and you have to have this amazing trust that everyone else is going to do his or her job well. When that happens, the evenings turn out to be particularly magical. It's a combination of a lot of things. It's not necessarily just the big theaters with the big budgets that provide the great evenings. There are other intangible factors involved. One of the most moving times I had in the opera house was in St. Louis, which is a very small theater, doing a piece called Paul Bunyan by Benjamin Britten. It's certainly not a great opera. There are a lot of problems with it. It's very early and very awkward at times, and has some very undeveloped sections and a lot of characters, some of which are extraneous to the story. But the ambiance of the production and the company and the music and the size of the theater... I had trouble emotionally at the end of every performance, and I'd been involved in the work for weeks. There was just something about how everything came together in that situation. I think back on that as one of the great performing experiences I've had, and I think the audience felt it as well. So it's not just how much money you spend and how big you make the production and how many superstars you engage or how big the chorus is. There are other factors involved in making great evenings at the opera.

BD: And you are one of those factors!

DP: We consider the chorus a critical factor in the success, especially in operas like Meistersinger. There's nothing like the sound of the chorus at the end just summing up everything that the opera is about. If you can get the right quality of sound with the orchestra, that amazing C major ending is the most incredible thing in opera.

= = = = =

Bruce Duffie has posted some of his writings online. Visit

his personal website http://www.bruceduffie.com . In the next issue

of The Opera Journal, which will be devoted to Verdi, his guest will be

baritone Alexandru Agache.

- - - - -

= = = = = = =

- - - - -

©2001 Bruce Duffie

First published in The Opera Journal, September, 2001.

Photos added for this website posting courtesy of Lyric Opera of

Chicago.

* * * * *

Be sure to visit Bruce Duffie's Personal

Website .