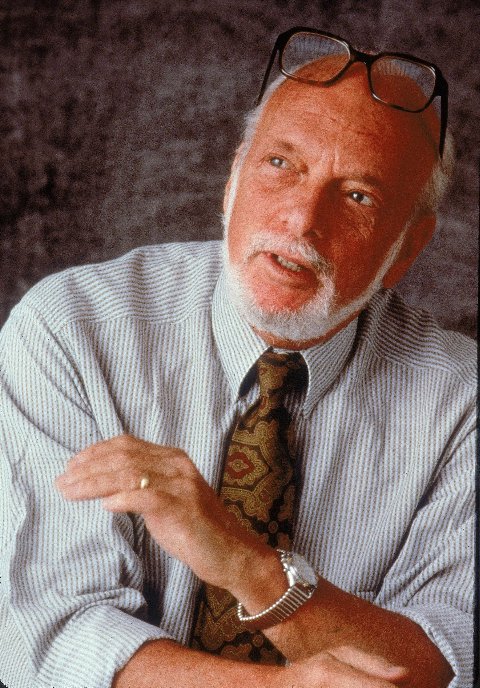

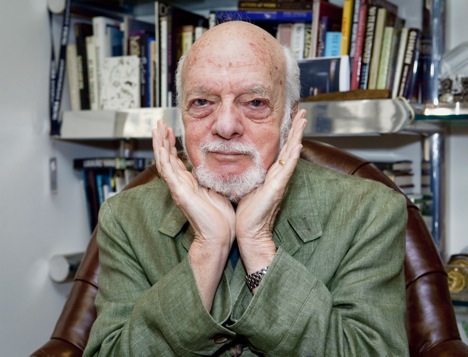

Harold Prince

Harold Prince Harold Prince: A pleasure.

Harold Prince: A pleasure.  BD: Why?

BD: Why?  HP: Yeah, you bet I would. I’d like to.

HP: Yeah, you bet I would. I’d like to.  HP: A lot. Oh I love it. That’s what makes directing

fun as far as I’m concerned, the material in context with the life of the

author, with the period he’s writing about, with political currents.

I’m very politically oriented so I’m very interested in the politics beneath

a piece of work, and so much opera has politics informing it.

HP: A lot. Oh I love it. That’s what makes directing

fun as far as I’m concerned, the material in context with the life of the

author, with the period he’s writing about, with political currents.

I’m very politically oriented so I’m very interested in the politics beneath

a piece of work, and so much opera has politics informing it. | Director and producer Harold Prince has won

20 Tony awards and received the National Medal of Arts in 2000 from President

Clinton for a career spanning more than 40 years, in which "he changed the

nature of the American musical." Prince attended the University of Pennsylvania

and graduated in 1948. He first emerged as a producer in New York in 1954

at the age of 24 with a production of The Pajama Game at the

St. James Theater on Broadway. He produced Damn Yankees the following

year and won Tony awards for both productions. Among others, Prince also produced

West Side Story, Fiddler on the Roof, Fiorello!

and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. As a director,

he has worked on the premiere productions of She Loves Me, Cabaret,

Company, Follies, Candide, Pacific Overtures,

A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd, Evita,

The Phantom of the Opera, Parade and Bounce. Among

the plays he has directed are Hollywood Arms, The Visit, The

Great God Brown, End of the World, Play Memory and his own

play, Grandchild of Kings. His opera productions have been staged at

The Chicago Lyric, The Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, Houston Grand

Opera, Dallas Opera, Vienna Staatsoper and the Theater Colon in Buenos Aires.

Currently, Prince is working on a new national tour of Evita, as

well as an updated version of The Phantom of the Opera set to open

in 2006 at the Venetian Hotel in Las Vegas. His film credits include movie

adaptations of The Pajama Game, Damn Yankees and A Little

Night Music, starring Elizabeth Taylor. He also directed the original

screenplay Something for Everyone made for National General. Prince

has also directed several notable television productions, including Candide

as a part of "Live from Lincoln Center" and a RKO-Nederlander production of

Sweeney Todd. In addition to his work in the theater, Prince

has served as a trustee for the New York Public Library and on the National

Council of the Arts of the NEA. He was a 1994 Kennedy Center Honoree. [Biography from the Kennedy Center]

|

This interview was recorded in Chicago on November 11, 1982. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1990. This transcription was made and posted on this website early in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.