Bruce Duffie:

You're a composer...

Bruce Duffie:

You're a composer... BD: Do you not

wish to teach others your technique and the things you have learned?

BD: Do you not

wish to teach others your technique and the things you have learned? BD: Will there be

more operas?

BD: Will there be

more operas? BD:

But you

don't want the public to stay away from it because they see you feeling

it is inadequate, do you?

BD:

But you

don't want the public to stay away from it because they see you feeling

it is inadequate, do you?

|

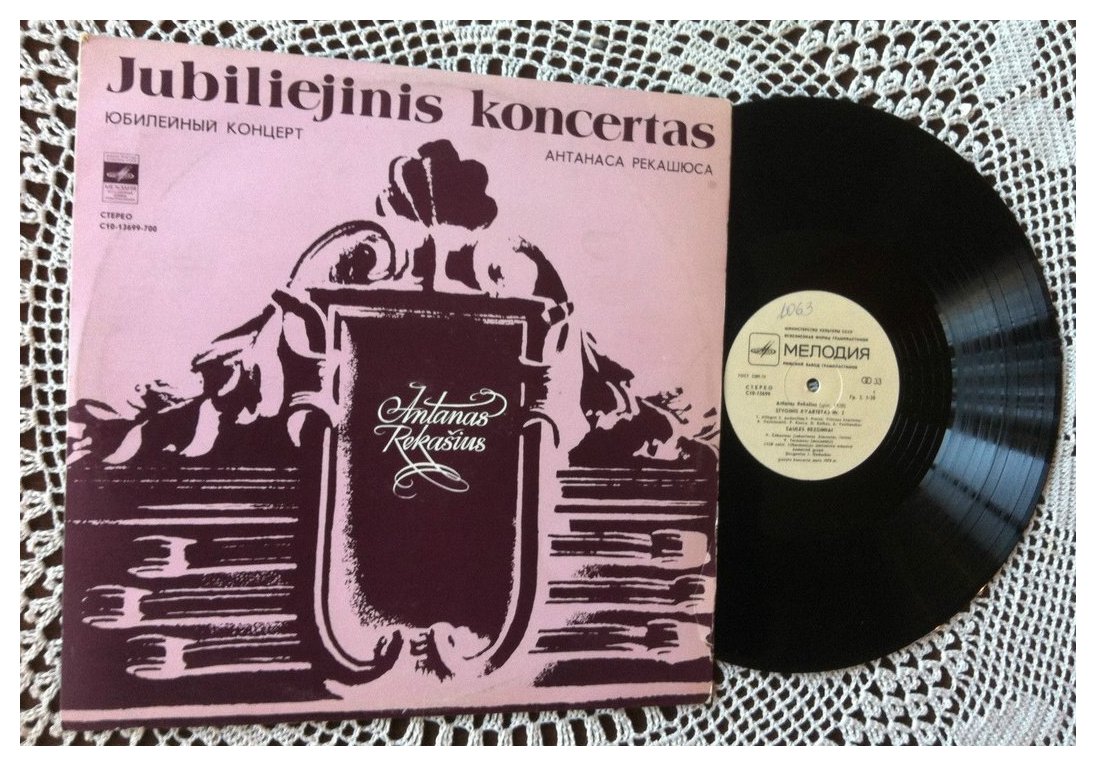

Composer found dead

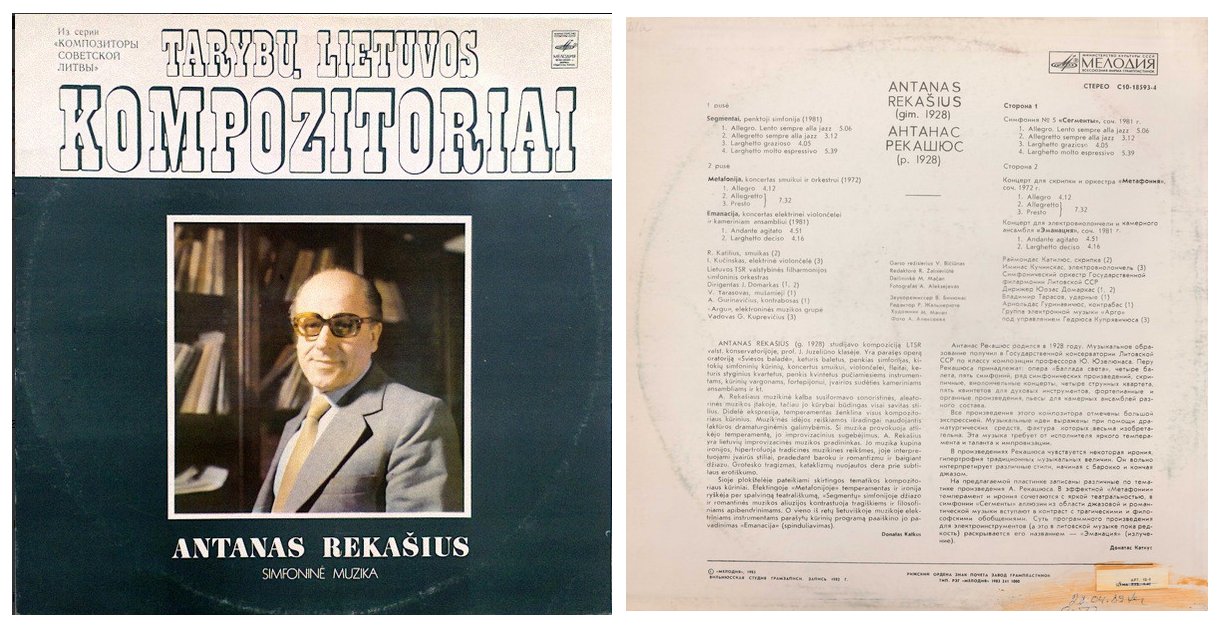

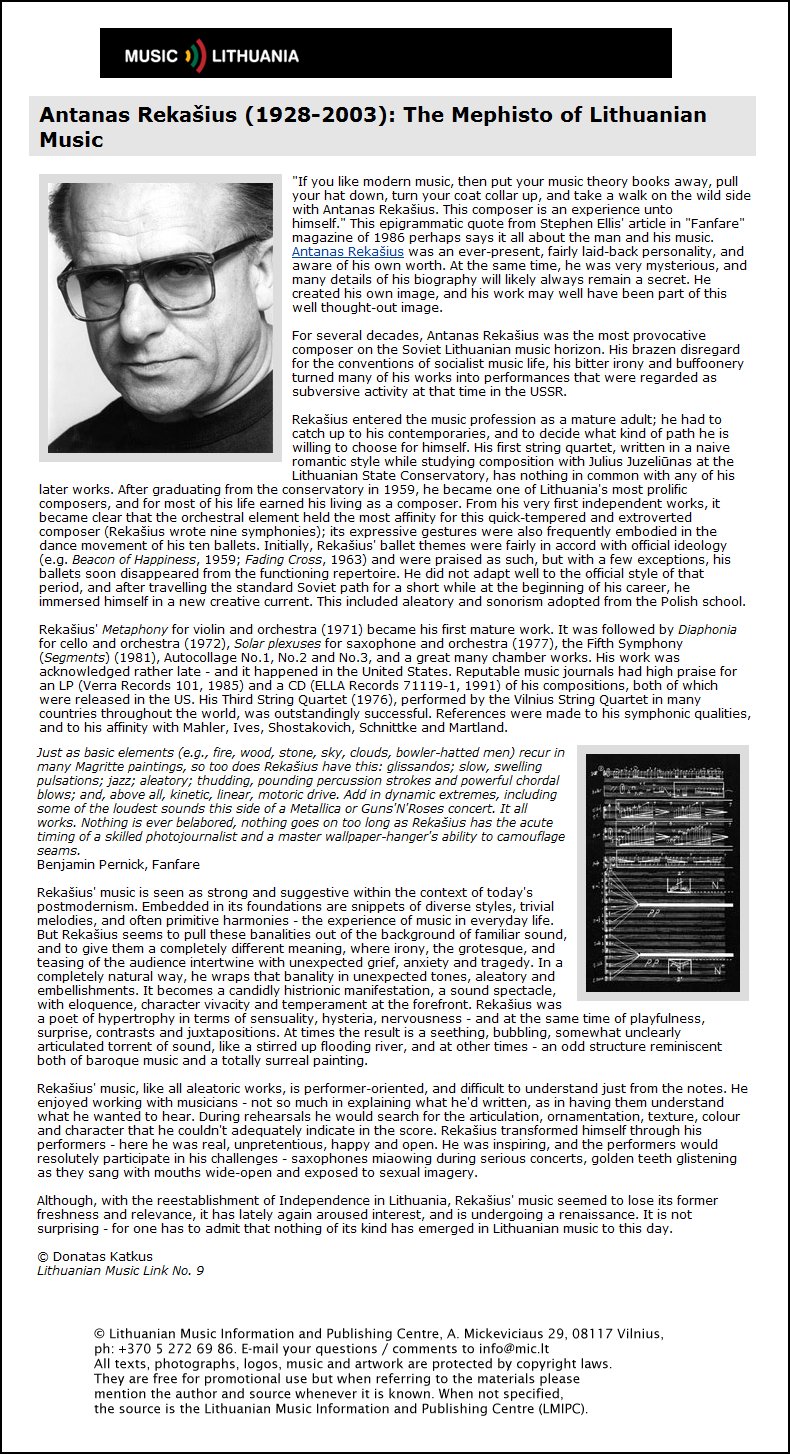

An elderly Lithuanian composer who had

fallen on hard times has been found shot dead in his flat in Vilnius.

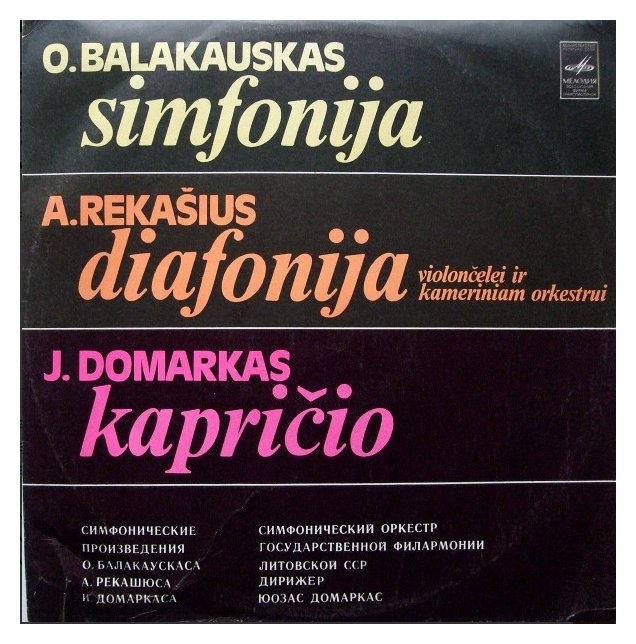

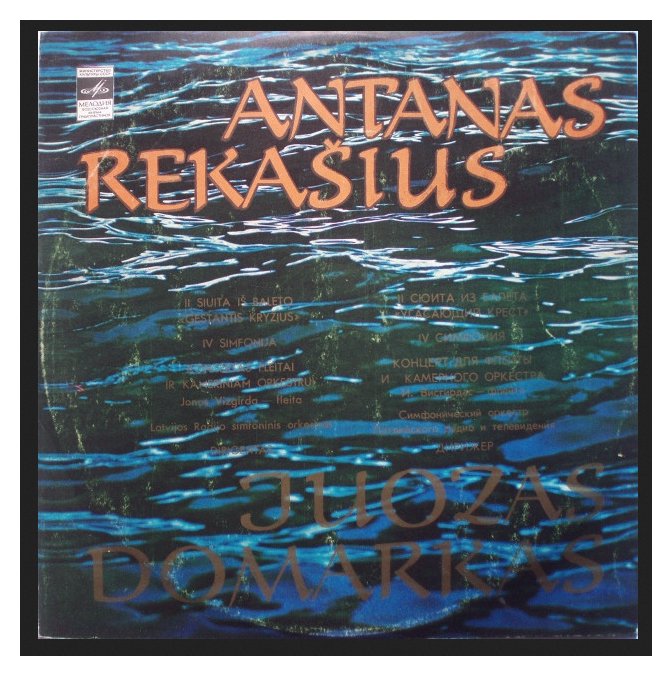

A gun was found by the body of Antanas Rekašius who had a bullet wound to the head and police suspect suicide. Rekašius, 75, had been living in poverty and barely able to pay the bills on his three-bedroom apartment. His work, which included symphonies and ballet music, was performed both in the ex-USSR and abroad, and was known for its humorous touches. Worried about his lack of income, he had been suffering from depression, police in the Lithuanian capital said. Rekasius's compositions had a non-conformist quality and were full of humour and the grotesque, the Lithuanian Music Information and Publishing Centre writes.

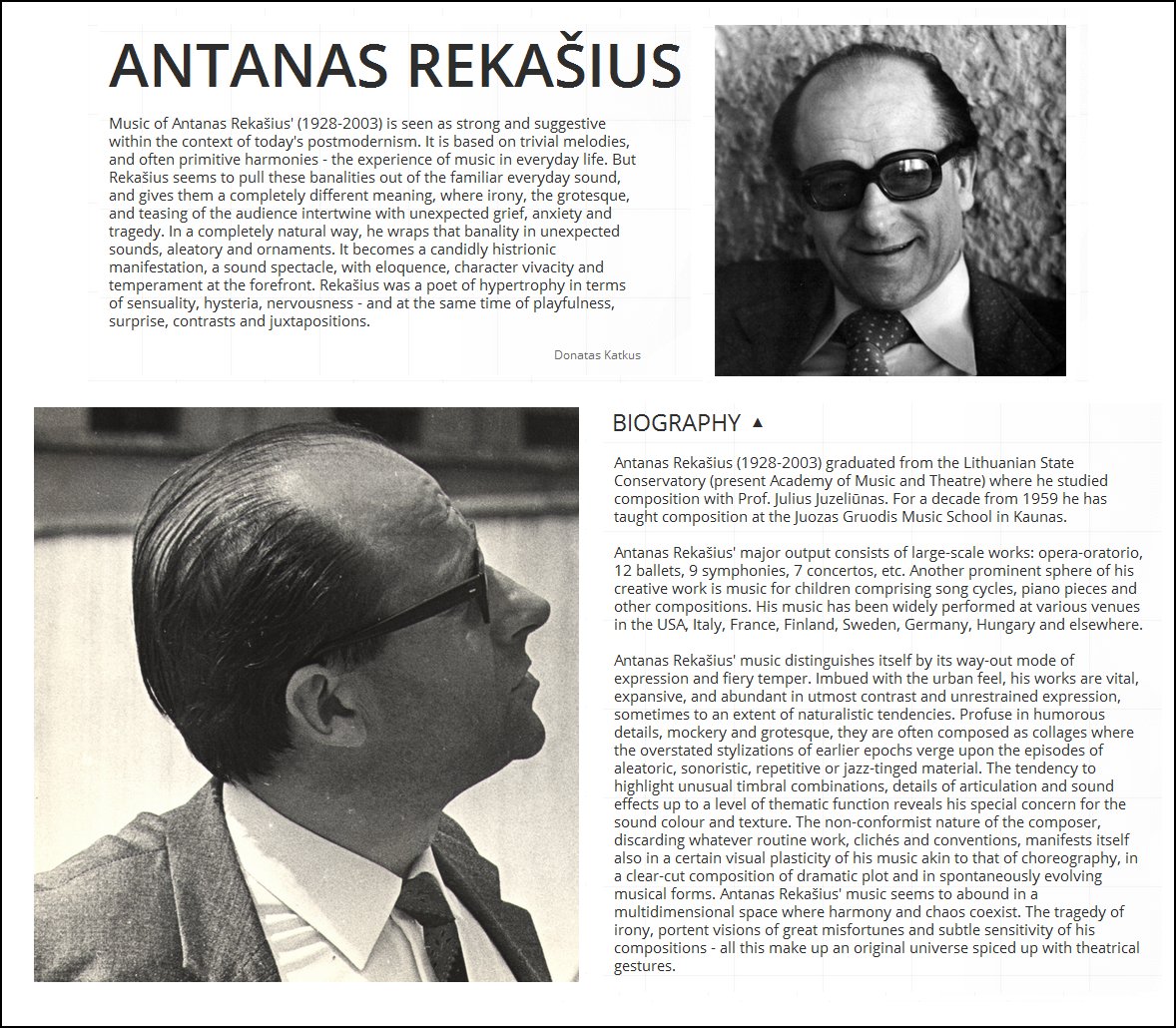

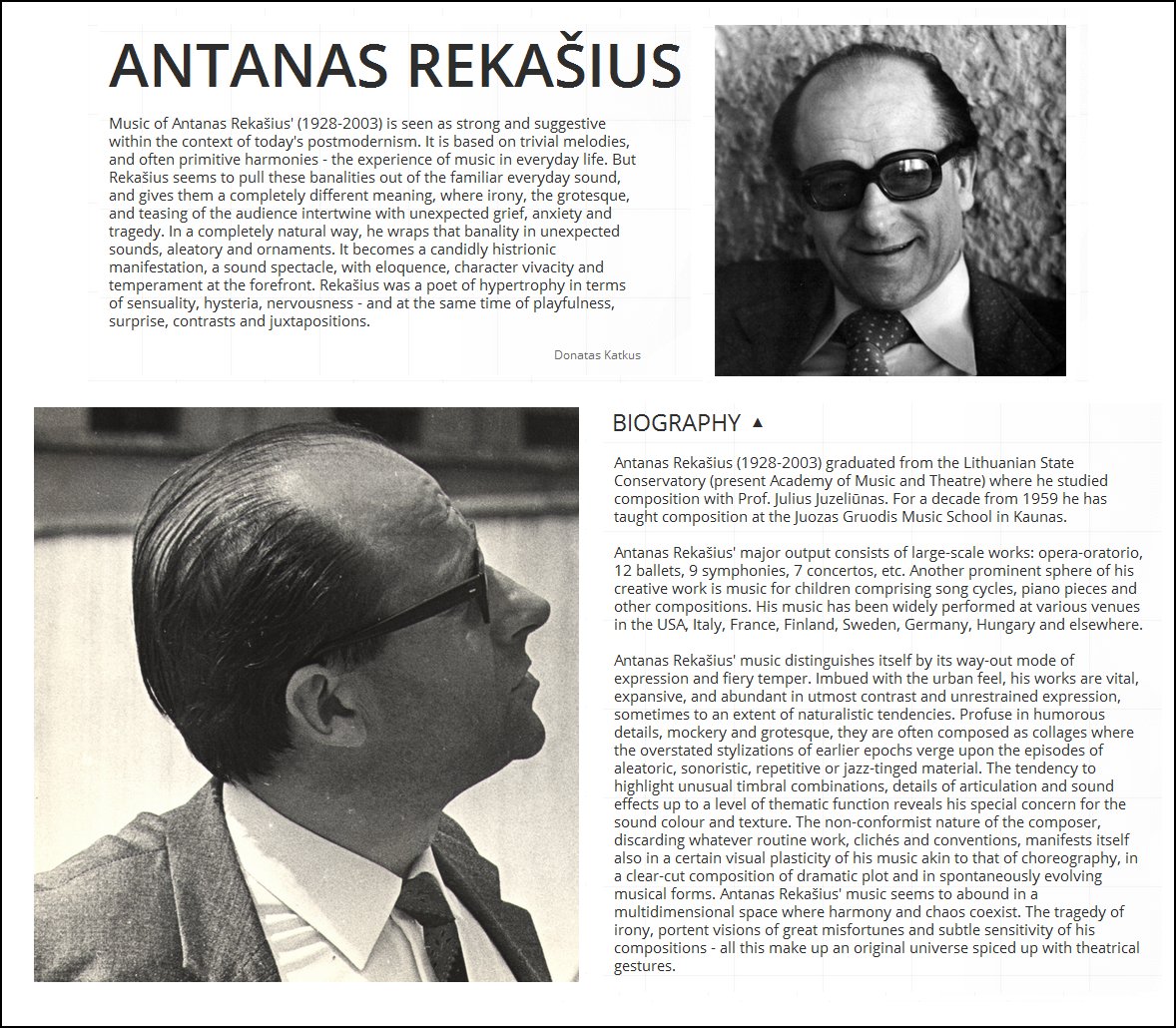

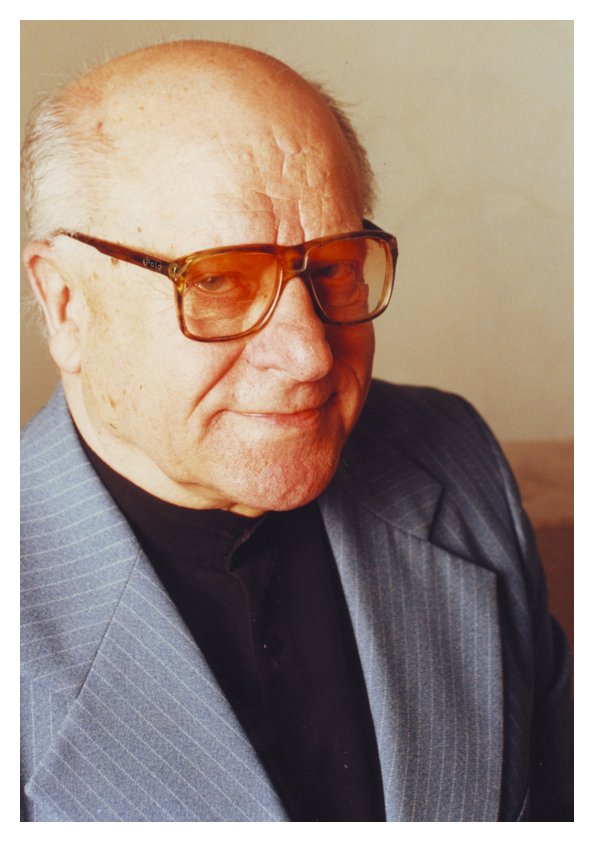

ANTANAS

REKAŠIUS

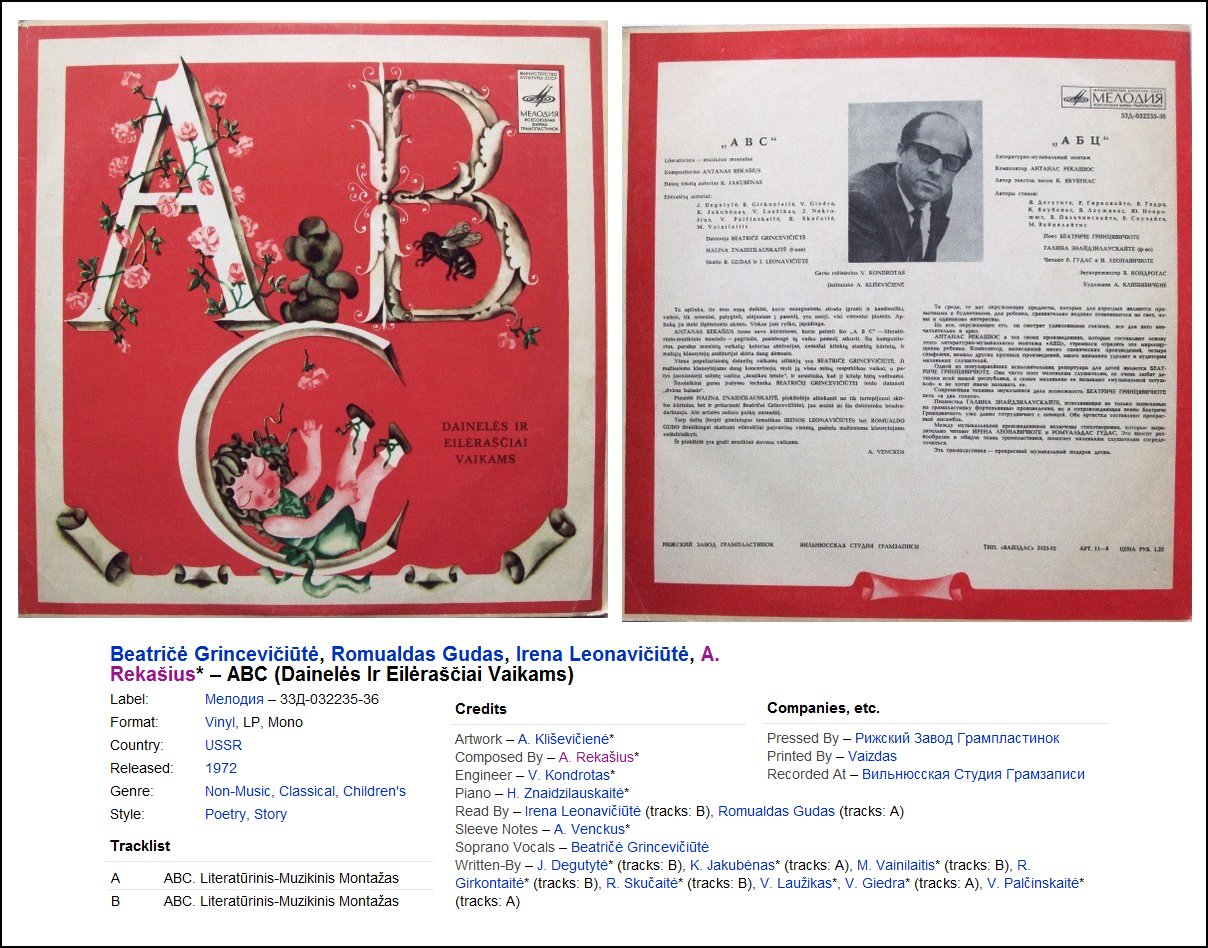

Apart from numerous symphonies and ballets, he wrote music for children including song cycles and piano pieces. The Baltic Music Information Centre once described him as "the most controversial composer on the Lithuanian Scene... his fondness for clowning sometimes overshadowing the serious nature of his work". Stunts he employed included switching off the lights for the finale of his fifth symphony and once having singers bare gold teeth at the audience. Antanas Rekašius's work was performed in the United States, Italy, France, Finland, Sweden, Germany and Hungary, as well as Lithuania and Russia. |

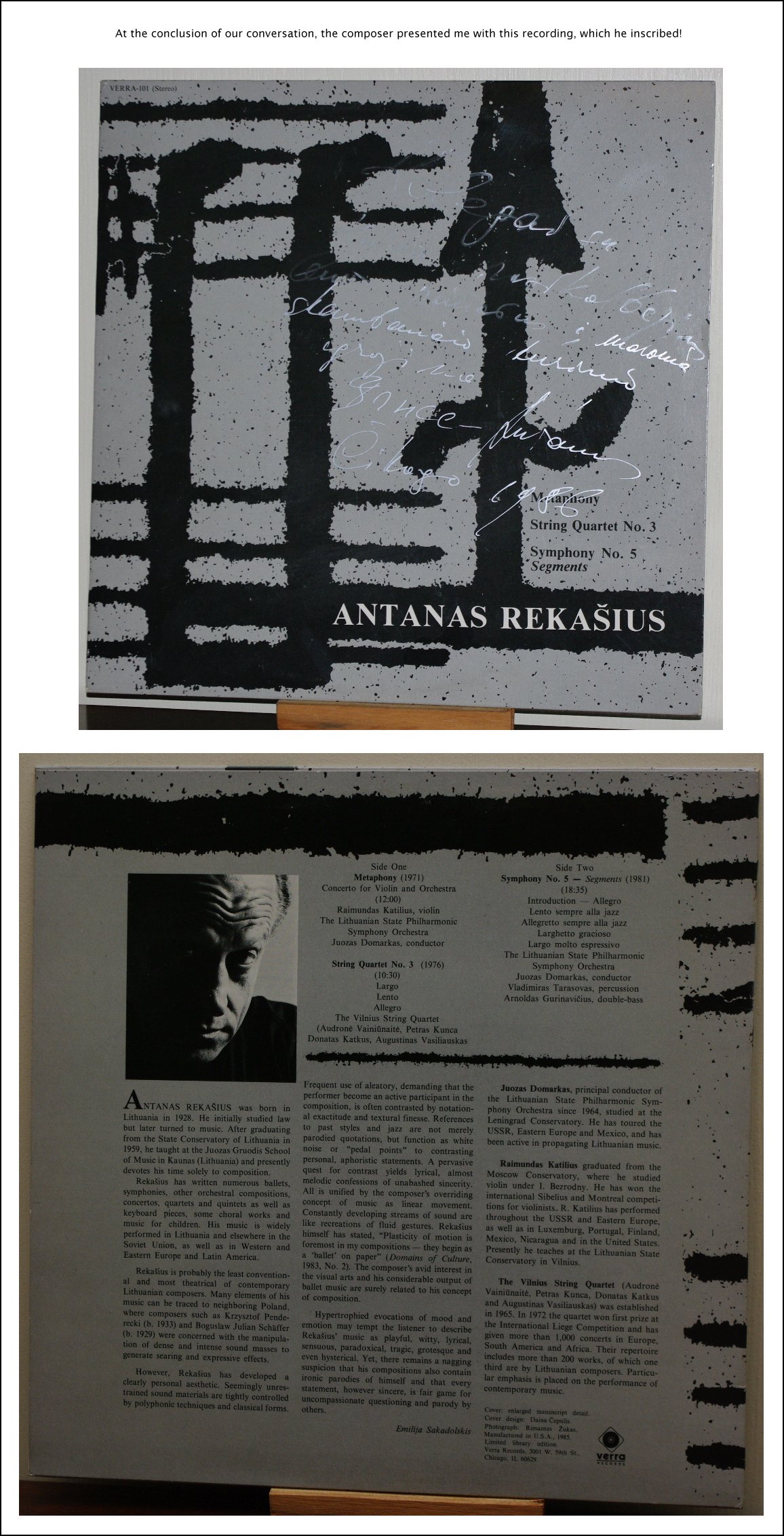

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on March 31, 1986.

The simultaneous translation was provided by Mykolas Drunga, Associate

Editor of Draugas, the

Lithuanian World-Wide Daily. Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNIB in 1988, 1993 and 1998. A copy of the audio

tape was placed in the Archive of

Contemporary Music at Northwestern

University. This transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.