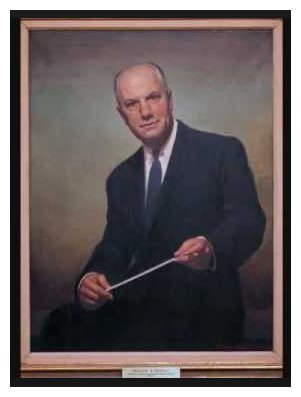

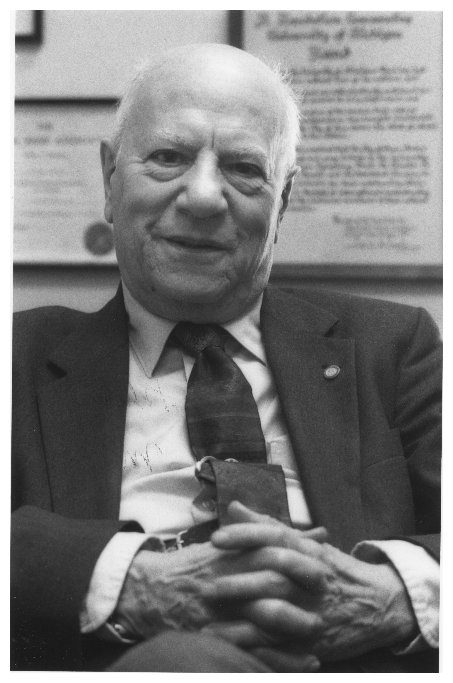

William Revelli

Director of Bands

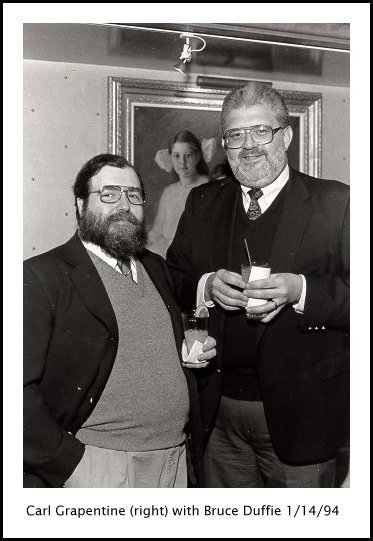

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

While in High School in Evanston, Illinois (1964-68), I participated in

most of the musical groups. I sang in the various choruses and

ensembles, and played bassoon in the bands and the orchestra. I

was also the music librarian! The rehearsal rooms and music

offices were next to the auditorium, and I truly lived at that end of

the building. Upon graduation, they gave me a small plaque of

appreciation — the first of

its kind, and, to the best of my knowledge, still unique. [To see

a photo, click here.]

It was a terrific

experience. I learned a lot and it formed the basis for the rest

of my life.

During that time, one of the band

directors was a Michigan graduate,

and he persuaded his old mentor, William Revelli, to come and be the

guest conductor. Our director made it clear that we would not

really appreciate this special event until much later, and that turned

out to be the case. We played — presumably well — and continued with our lives and

families and careers in many fields. It was, indeed, a

great experience, but for us it was just another highlight. Only

in retrospect do we now understand that this was more. It was a

personal link to the wonder that is “The Band” in the very best sense.

During that time, one of the band

directors was a Michigan graduate,

and he persuaded his old mentor, William Revelli, to come and be the

guest conductor. Our director made it clear that we would not

really appreciate this special event until much later, and that turned

out to be the case. We played — presumably well — and continued with our lives and

families and careers in many fields. It was, indeed, a

great experience, but for us it was just another highlight. Only

in retrospect do we now understand that this was more. It was a

personal link to the wonder that is “The Band” in the very best sense.

At the end of July of 1991, Revelli appeared with the Wheaton,

Illinois, Municipal Band for a concert which was filmed as part of a

public television documentary about Sousa. While he was in

the Chicago area, I had the opportunity to speak with him immediately

after this event. As I set up the tape recorder, he asked if I

knew

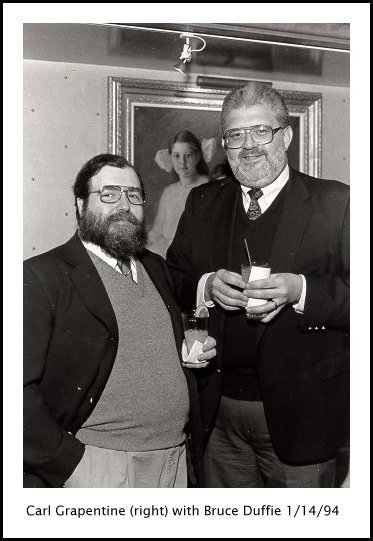

Carl Grapentine, his own stadium announcer. I was glad to tell

the conductor that Carl was on the staff of WNIB, Classical 97

(1990-1996), the station where I was employed (1975-2001). This

pleased him, and he related a brief story...

Carl

was an oboe in my band when we went to Europe my last

year. I auditioned him for the job, and for announcing at our

stadium.

The way I do that is to have them go up into the stadium while I stand

down

on the fifty yard line and have him announce as I listen. We

had five of them try out, and after he come on I listened to the other

two [laughs] but I’d already said, “This is the voice I want.”

He’s a

good boy.

Revelli retired from Michigan in 1971, but as I put together this

website presentation (2013), Carl still goes back on Saturdays during

the football season to do the announcing.

Besides Sousa and other band-specific topics, Revelli spoke with me

about many things. Here is that conversation . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie:

With the great popularity of bands in high schools and colleges all

over the country, why are there no professional bands, like there are

professional symphony orchestras?

William Revelli:

You’re absolutely right in that there aren’t any. There was a

time when we had the Sousa Band, but during that time there were other

fine professional bands that people don’t talk about. They

weren’t as popular as the Sousa Band, but the predecessor was Patrick

Gilmore. He was called “The Irish Orpheus.” He had a larger band than

Sousa had and he traveled all over the world with it. In fact, he

was also a tremendous showman. In Boston Commons, down in the

commons there, he had a festival with a two thousand piece band.

There were over a thousand anvils from the fire department and

everything else in Boston doing “The Anvil Chorus ” from Il Trovatore. This is the

kind of showman he was. He built a big palladium for his

concerts, but it flopped. People didn’t come. I don’t know

why that was, and I believe finally it burned down. That was the

predecessor of Sousa. Then during Sousa’s later years there was

Patrick Conway, Creatore, Innes, and Liberati. They were about

forty-five or fifty-piece bands that traveled all over the United

States. They never went to Europe, but Sousa made five or six

world tours with his band. People don’t know about that.

BD: Why do we

remember Sousa and not these others?

BD: Why do we

remember Sousa and not these others?

WR: His

marches. They played Sousa marches.

BD: And also

transcriptions?

WR: Yes, oh

yes. Sousa played transcriptions almost exclusively because there

wasn’t any original band music except his own. There is a little

story about when he played the first performance of The Victors march by Louis

Elbel. Sousa and his band were there to do a concert on campus

and the composer gave him the parts. He played it that night, and

the composer says Sousa said, “It was the third greatest march ever

written.” Elbel asked, “What about the other two?” and Sousa

said, “Well, I wrote those.” [Both laugh] It’s a little

story, but he did like the march. Sousa was never like “The Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene

Ormandy, Conductor,” or “The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Georg

Solti, Conductor.” It was “Sousa and his band.” Now psychologically that may

not mean much to you, but it does, because it was not “The Sousa Band.” Sousa was first. You

went to hear Sousa and his band.

BD: Did he

want it that way?

WR: You bet

he did! In fact, his first band was not “Sousa and his Band.” His first band was “The Sousa Band, John Philip Sousa,

Conductor.” Blakeley, who was his manager,

was a very astute man. John Philip Sousa can give great credit to

Mr. Blakely, believe me! He was a Barnum. He knew how to

sell, and he did. Sousa listened to him, too, believe me. I

don’t think Sousa himself could have done that. I often thought

that Dr. Goldman, with the Goldman Band, made a mistake by trying to do

it himself. He never had a manager that sold the Goldman

Band. He did it himself. But if he’d had a Blakeley, he

could have done it.

BD: Is this

what you spent thirty-six years in Michigan doing — selling band music?

WR: Well,

indirectly. By that I mean every single student that I conducted

that was a music major that went out to conduct high school bands or

trade school bands, junior high bands, college bands. I was a

disciple, in a way, for bands and band music and better band

music. So I think yes, that indirectly I am responsible for a

great emphasis in the band world. I’m bragging a bit, but I’m

doing it because I believe in it. We have, for instance, the

American Bandmasters Association, which is a very elite group of band

conductors. You cannot apply for admission to it. You have

to be nominated and elected to it, and it’s pretty severe. And

there’s more Michigan men who have succeeded in becoming members of the

ABA than any other. There are more university band directors in

America that are from Michigan. We sold the band program — not municipal bands but college

bands. To answer your question about where are the professional

bands, there aren’t any. There were in those days. One of

the few remaining professional bands that no longer has a budget was

the Long Beach Band which Herb Clarke conducted for years. He was

the solo cornetist for the Sousa Band for many years, and assistant

conductor for Sousa. If you ask me why they are no more, it’s

money. I ask you why is there only one symphony orchestra in New

York City?

BD: But there IS a

symphony, and there are chamber groups and opera companies, but no band!

BD: But there IS a

symphony, and there are chamber groups and opera companies, but no band!

WR: No, not

since the Goldman Band. There’s nobody to fund it.

BD: Should we

try to get this kind of thing going?

WR: Yes we

certainly should, and tonight was an example of the image of what I

could see as the true municipal band. Those people had a great

night of enjoyment. They appreciated it. That was evidenced

by their response. They had a good time.

BD: So now

you have automatically two thousand band boosters right there.

WR:

Exactly. We need that in the United States; we need ten thousand

Wheatons. You’d be surprised... I don’t know if you’re

aware of it, but the revival of the community band is

astonishing. For instance, let’s take Michigan alone. Ten

years ago there weren’t more than four or five community bands in the

state of Michigan that you’d want to hear. Today there’s fifty.

BD: Now you

say “that you want to hear.” In other words, they’ve gotten up to

a certain level?

WR: Their

performance standard is such that you enjoy going to the concert and

it’s not claptrap. The concert this evening had some very good

repertoire in it. The young college band director is averse to

doing transcriptions. They want original material and I’m for

that, but because it’s new and original doesn’t mean it’s good, or that

old music is bad.

BD: Shouldn’t

there be a balance of some new things and some transcriptions?

WR: Of

course. Now you’re talking! You see, back in Sousa’s day

ninety per cent of the music was transcriptions because there wasn’t

any original band music. The only band music that you found that

was original was his! He didn’t just write marches; he wrote

suites.

BD: Is there

any kind of correlation between what Sousa did for the band and what

Kreisler did for the violin?

WR: Very much

so. That’s a very good analogy with Kreisler. People,

including me when I was a kid, went to hear his encores... Schoen Rosemarie, Liebesfreud, Old Vienna and all those little

encores. [Begins to sing one of them softly] We went to

hear them. It’s like Horowitz. There was no way Horowitz

could ever end a concert without playing Traumerei. There was no way

he was going to get off that stage! Now, if you’re going to play

Sousa you’d better play Stars and

Stripes because they’re going to insist on it. Sousa was

not only a legend, but he made a big contribution and will continue to

do so. For instance, there’s been thousands of marches written

since Sousa died... thousands, and where are they? They are no

different than the pop tunes that last three months.

BD: What is

it about a Sousa march that lasts?

WR: It’s not

the form. It’s a four-bar introduction to sixteen or thirty-two

bars, a break-up strain and back again. It is sonata form. Stars and Stripes is the longest

march he wrote. It has more measures in it than the rest of

them. He wrote a melody that you could hear a couple of times and

sing.

BD: But you

don’t get tired of it.

WR: Yes,

because it’s good. You bet. Rhythmically, harmonically, the

structure of it; he was a master at putting the voices where they

belong. Color. And he never once played them the way he

wrote them. We have men going around the country saying, “This is

the way Sousa played his marches.” They must have never heard

him. I heard him twenty-six times! There’s a young man here

from the research center and he showed me some parts of an encore book

of Sousa. There’s Herbert Clarke’s cornet part in which he says,

“First strain, tacit.” I’ve been doing that for fifty

years! I was so proud to see that today because I’ve been doing

that all along! Here was the original Herbert Clarke cornet part

with the Sousa Band encore stating, “Tacit, first time, enter second

time.” That’s all the editing. It’s not written that

way. For instance one time I heard the piccolo variation on the

harp. I heard Bill Bell do it on the tuba with the Sousa

Band. [Sings] He got the trills in there on his tuba clear

as a bell! That was Sousa. He was never satisfied. I

asked him if he would object to my editing his marches and he said,

“Have you heard my band?” I said, “Twenty-six times.” He

was very abrupt at these kind of things and said, “Do I edit

them?” I said, “You never play them the way they’re

written.” He said, “Well, that’s editing.” Then he

said, “As long as you don’t change the melody and you don’t change the

harmony and you do not change the rhythm, you can do what you want with

the color of it. If I like it, I’ll accept it. If I don’t,

I’ll tell you so.” But he was constantly changing his ways of

presenting the color.

*

* *

* *

BD: What

advice do you have for someone who wants to write music for the concert

band?

WR: My first

advice would be to write music, the score, for the public that

appreciates what the band audiences understand, and which they will

receive and accept. Now let me explain what I’m saying.

There’s a lot of wonderful contemporary music being written.

Unfortunately, it’s not accepted by the public.

BD: Because of its

density?

BD: Because of its

density?

WR: Its

complication. It’s complicated. I ask you, how many new

operas will have been presented by the Metropolitan in the last decade?

BD: Very few

at the Met, but hundreds in Europe. They’re much more

experimental over there.

WR: They sure

are. Not only that, they have the money to do it.

BD: That’s

true. State subsidy.

WR: You

bet! The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra is eighty-five per cent

subsidized by the government. How much does the New York

Philharmonic get? Zero from the government.

BD: Maybe one

per cent from the National Endowment, and that’s it.

WR: That’s

right, and that’s being cut considerably. So there’s the

difference. It’s the sense of values. There are more little

small town opera companies that you don’t particularly enjoy all the

time. [Laughs] They’re broken down singers of the past or

they’re aspiring young artists with a little tiny orchestra in the pit,

but they’re still playing Verdi and Aïda

and so on. The Italians were brought up on that; that’s their

history, whereas in Germany it was Beethoven and Brahms, and in Russia

it was Tchaikovsky and so on. But the band, the voice of the band

is truly Americana since the Revolutionary War. It’s rather

interesting, too, that where the band really began was in the New

England states. I don’t like to say it, but it’s a fact that the

worst bands in schools in the United States are where the band was

born, in New England. They don’t support it.

BD: You’re

talking about support and what you think is important. Let me ask

the great big philosophical question — what is the purpose of music in

society?

WR: I think

it has three or four purposes. One of the handicaps for the band

is it has become traditionally known as an entertaining medium because

of its tremendous versatility. Unlike the orchestra, the band can

play in all kinds of occasions. It can march, it can play for the

Fourth of July Celebration parade, it can play for a military parade,

it can play at a gridiron, it can play in a basketball tournament, it

can play in at a hockey game, they can play everywhere. That’s

number one. It’s an entertainment kind of a medium. In

fact, take the high schools. Many times they threaten to take out

the band and sports. The band’s been related to sports, and that

always hurts me. I said, “What’s it got to do with sports?”

Well, because it plays at the half-time, and the people’ll say, “We

won’t have a band for halftime! We’ve got to have a band!”

That was one point. The other is the educational features of

it. It has tremendous educational value. I’ve been to Japan

three times and helped them get their band started. You want to

watch this program in Japan. It’s coming. They don’t just

make Sonys and Yamaha motorcycles and so on. They’re spending a

tremendous amount of money on the youth and music in Japan, in the

public schools! So the purposes and the objectives of the band

program are many. Let’s take an example. School starts in

September. What’s the band director’s first obligation? To

get that band ready for that first football game! He better have

it there! The board of education and administration say, “You

will have it there.” When I went to Hobart, Indiana, they’d never

had a band and no instrumental program at all. I went to the

superintendent, Mr. Dickey, after school had started a couple of weeks

and asked his permission to organize an instrumental program. Now

he was a Hoosier, brought up in Hoosier-land and he said, “We have some

problems. Number one is that there’s no place to rehearse.

Every room’s taken with classes. The schedule’s already made, so

there’s no time for rehearsal. Classes are scheduled. And

there’s no budget.” But he said, “Go right ahead. If you

can get it started, find a place to rehearse, find a time for

rehearsals, you have my permission to begin.” He added, “By the

way, I think it would be wonderful.” Now this is an educator, a

superintendent, who said “I think it would be wonderful if we could

have five or six kids play for the basketball games.” That’s his

concept of what music education was about! I went out of his

office quite disappointed. Finally I said, “Wait a minute.

You got what you asked for. He gave you his blessing to start

it.” We rehearse at seven o’clock in the morning in the chemistry

lab because the professor and a teacher of chemistry was a good friend

of mine. We had to move everything out and put it back, and oh

God get every instrument out of the attic and rent some others from the

Chicago Instrument Company. But we got started. That’s the

way we started! Remember, while you’re out on a gridiron getting

that band ready for that first game, the orchestra conductor’s already

got the orchestra in the rehearsal room playing, maybe, a Beethoven

symphony or a Haydn symphony

— or whatever — so, education-wise, the band has been

at a disadvantage. Its very versatility has been its greatest

enemy. Because it can do everything in so many places, they use

it. It’s a window-dresser for the community!

BD: Where

should the balance be, then, between the entertainment and some kind of

artistic achievement?

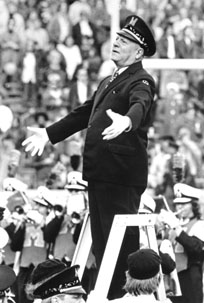

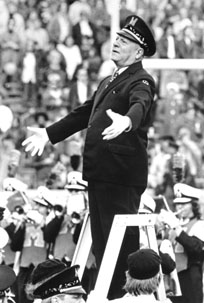

WR: That’s a good

question, and the answer is that if the conductor is truly a serious

musician and he’s an educator, he will have both. There’s no

reason in the world that a football band has to play badly.

That’s the conductor’s responsibility. My men — and

women, later — in the Michigan marching band hated

my guts when I would work them hard before the last game of the

season. We’re playing on national television the next day and we

hadn’t been through the show once completely without stopping.

It’s snowing, it’s cold, it’s the last game and Revelli’s stopping that

band and tuning it and trying to get it together! They’re

frozen! They’re so cold, the valves are cold, their fingers are

cold, and Revelli’s saying, “The third cornet, let’s hear you.”

They said, “This guy’s impossible!” Then we would play and the

audience would receive us they way they did, and they were so

proud. They knew it was good. Then Revelli was okay, you

see. So that was that. There you are. I told them,

“The C-natural on your trumpet, half-note, forte, is no different; you

don’t read it any different, you don’t play it any differently than you

would if you were playing with the symphony at Carnegie Hall.”

You’ve got to approach it that way. You don’t just blow your

brains out on a gridiron because everybody’s up, up, up, rah, rah,

rah. I don’t go for that. The tone of my concert band and

the symphony band, at least the objective was not different. It

was educational all the way down the line. I know so many bands

just blow, you know. There’s no musicianship about it, not even

the intent at being musical.

WR: That’s a good

question, and the answer is that if the conductor is truly a serious

musician and he’s an educator, he will have both. There’s no

reason in the world that a football band has to play badly.

That’s the conductor’s responsibility. My men — and

women, later — in the Michigan marching band hated

my guts when I would work them hard before the last game of the

season. We’re playing on national television the next day and we

hadn’t been through the show once completely without stopping.

It’s snowing, it’s cold, it’s the last game and Revelli’s stopping that

band and tuning it and trying to get it together! They’re

frozen! They’re so cold, the valves are cold, their fingers are

cold, and Revelli’s saying, “The third cornet, let’s hear you.”

They said, “This guy’s impossible!” Then we would play and the

audience would receive us they way they did, and they were so

proud. They knew it was good. Then Revelli was okay, you

see. So that was that. There you are. I told them,

“The C-natural on your trumpet, half-note, forte, is no different; you

don’t read it any different, you don’t play it any differently than you

would if you were playing with the symphony at Carnegie Hall.”

You’ve got to approach it that way. You don’t just blow your

brains out on a gridiron because everybody’s up, up, up, rah, rah,

rah. I don’t go for that. The tone of my concert band and

the symphony band, at least the objective was not different. It

was educational all the way down the line. I know so many bands

just blow, you know. There’s no musicianship about it, not even

the intent at being musical.

BD: So is

this your advice, then, for people who want to conduct bands, is to be

musicians first?

WR: First,

yes. In fact, I would like to see that the emphasis in the music

education field be placed upon performance for four years. Every

one of these band conductors would go through a very rigid performance

program. I did it. I never got a music education degree

until after I had my performance degree. I played seven years

professionally before I ever took a course in music education. I

passed about nine-tenths of the courses for music ed without even going

to class. I took the exams for placement on performance, playing,

history and theory. I never had any problems with that.

BD: You

started out on violin.

WR: I am a

violinist. I never played anything else. Sousa was a

violinist.

BD: [With a

gentle nudge] Then why didn’t you organize the world’s greatest

string quartet instead of the world’s greatest band?

WR: [With a

big smile] Because I love the band.

BD: They why

didn’t you play cornet?

WR: I didn’t

think that made any difference. Fact of the matter is, let me ask

you what is Solti’s background? [See my Interviews with Sir Georg

Solti.]

BD: Piano.

WR: Well, why

didn’t he play a violin? He’s an orchestra conductor. Why

was he a pianist? What is the difference? What was

Toscanini? He was a cellist. Saul Caston, conductor of the

Denver Symphony was a trumpet player. [As if giving the

interviewer an oral exam] What was Eugene Ormandy?

BD:

[Responding correctly] A violinist, I believe.

WR: Where’d

he play?

BD: He

started in Hungary.

WR:

Right. He had a manager that came over to the U.S. and told him

he had a big concert tour, but he never had a date. Gene couldn’t

find a place to play, so he auditioned for the Capitol Theater where a

friend of his was conductor. He never played first violin in any

major orchestra. I think that first of all a conductor has to be

a good musician. I don’t think you can be a bad musician and be a

good conductor. There are many, many wonderful musicians who

would be awful conductors and vice versa. Why is it that with all

the great violinists we have in the major orchestras, who’ve had

twenty-five years experience of playing every symphony in the

repertoire, why aren’t they conductors? You can use another

analogy — some of the greatest baseball players

became awful managers. They were flops. Bob Zuppke never

played a football game, but he was just one of the great coaches of

Illinois. Fielding H. Yost was never a great player. He

never played football very much. Conducting is a talent. There

are so many areas of conducting that you’ve got to be a good

musician. You’ve got to have an ear, for instance. You have

to have a good ear to be a conductor. If you’ve got a bad ear,

forget it! [Both laugh] And I’ve had folks like that.

I wish I could conduct with the stick like they did, but they can’t

hear anything. God, the band plays all out of tune and they’re

making beautiful motions. I had a student in my conducting class

who wouldn’t believe this. He was a kind of an ego, and he made

the most beautiful gestures. [Demonstrates] So I thought,

how am I going to reach this guy? He had an ear like a

sock. He can’t hear anything! I have to reach him. I

have to make him believe. So I deliberately had the oboe player

play the English Horn part. The oboe’s in C and the English

horn’s in F. so it’s a fourth off. He played the whole solo and

the guy was conducting. When he got all through, I said, “Tell me

what was wrong with this.” “Well, I thought they didn’t make

enough crescendo here. I thought they—” I said, “Now just

hold everything. I don’t want to do this...” but I did it.

“It’s about time you realized where your weaknesses are. We’ve

got to do something about it. He’s playing the English Horn

part. He’s a fourth off. Every C he played was an F, and

you never heard it. You played accompaniment underneath it.

It was awful!”

BD: Did he

fix his problem or is he selling insurance now?

WR: Well,

he’s not selling insurance, but he’s not in music. He’s done very

well, incidentally. I’m guilty of changing some students into the

other professions. One is now a wonderful dentist. He’s got

some of the best clients in Cleveland there are. Big

people. He was in music ed, but he had nothing.

BD: So you

told him to get the heck out of music?

WR: Well, I

didn’t do it quite that way. I said, “I’m going to find out”

because he was bright. So I went to the registrar and looked at

his transcript. He had straight As in everything!

Mathematics, history, English, so on, and he had Cs in music. No

band director ever gives a C in music! They only know one letter

in the alphabet, and it’s A. Everybody gets an A! You get

an A if you’re there and if you can breathe. Anyway, I called him

in and I said, “Let’s have a talk here.” He was a freshman so it

was not too late. I said, “You don’t have to quit. We’ve

got seven bands, and this is a place for those kinds of bands.

But I think it’s time to switch before it’s too late.” That man

has thanked me and sends me wonderful gifts at Christmas! He

said, “Thank you, Dr. Revelli. When I think of what I might have

been... such a misfit! I really wasn’t that much interested in it

anyway.” Well, there you are. I was doing a clinic at

Missouri and I got there a little early and the teachers in the high

school were having their coffee break. I just couldn’t find the

band director, so I walked in and I asked if he was there. No, he

wasn’t there. I sat down and one of them started talking with

me. I said, “What do you teach?” He said, “Math.” I

asked another one, and she taught English. I asked another one,

and then one of them asked me, “What do you teach?” I said, “I

teach people.” You should have seem them. There were about

ten of them and they all seemed to think, “Who is this nut? This guy is

crazy.” [Both laugh] Finally one said to me out loud, “What’d you say?” I said, “I

teach people.” “What do you mean?” he asked, and I said, “Well,

through music. I happen to be a conductor and a teacher and a

musician.”

BD: Is that

what you do every time you get on the podium — teach the people both in front of you

and behind you?

WR: Every

time. Every time. I am a teacher. Toscanini was the

greatest teacher I’ve ever known.

*

* *

* *

BD: Are you

optimistic about the future of band music in America?

WR: I’m highly

optimistic about it. I have never been more thrilled and more

confident and overjoyed with what I see. I’m disappointed in many

things in the music education field, and in the bands in the schools I

am very disappointed, but more than ever in my life I’m convinced that

music education is here to stay. I have yet to see one program

that’s good where they have curtailed it. But we have so many

mediocre ones. We have so many that are so bad, unfortunately,

and they’re the ones that are in jeopardy. There’s too many of

them.

WR: I’m highly

optimistic about it. I have never been more thrilled and more

confident and overjoyed with what I see. I’m disappointed in many

things in the music education field, and in the bands in the schools I

am very disappointed, but more than ever in my life I’m convinced that

music education is here to stay. I have yet to see one program

that’s good where they have curtailed it. But we have so many

mediocre ones. We have so many that are so bad, unfortunately,

and they’re the ones that are in jeopardy. There’s too many of

them.

BD: How is

the burgeoning of electronic entertainment — the television and all of this — going to help or hinder the

advancement of concert music and band music?

WR: Perhaps

this may be one of the most crucial and vital areas that we must be

concerned about. All you have to do is to go to Hollywood.

I have friends who compose for the TV shows and what’s happening is

frightening. The musicians never even see each other. The

strings never see the brass because they’re in two different rooms and

they’re recorded at different times. It’s the electronic

age. It’s unbelievable! I was in Toronto judging conducting

last spring, and I happened to be in the restaurant to get

breakfast. It was crowded, and the table where I was sitting was

for two, and it was the only empty chair in the restaurant. A

young Japanese man came in. He was looking and couldn’t find a

place to sit. So I said, “Sir, if you would like, you may join

me. This seat is available.” So he sat down and we got

acquainted. He was very intelligent, about thirty-five years-old

and in the computer business. I’ve never met a more alert,

intelligent, interesting, fascinating man. I said, “What a

fascinating field you’re in.” “Yes,” he says, “It’s also the most

competitive. How would you like to be president of a corporation

that has a fifty million-dollar inventory that may be obsolete tomorrow

morning? That’s the field I’m in.”

BD: Do you

think the band will ever be obsolete?

WR: I don’t

think so any more than the orchestra would. Do you think that a

singer will ever be obsolete? A singer like Pavarotti or Domingo,

or whatever great singer?

BD: I hope

not. [Laughs]

WR: Who’s

going to produce the original sound?

BD: Probably

some electronic gizmo invented by the Japanese fellow that you had

lunch with.

WR: That will

duplicate the human voice?

BD: Right.

WR: Well, you

could be right. We kept on talking. They also make

synthesizers, so I told him about a guest-conducting engagement where I

wanted to play a certain piece but the second oboe just wasn’t good

enough. I mentioned that to the Dean and he said, “We can fix

that.” He went over and got his arranger, a young man, a very

sharp young fellow, and he sat at the synthesizer and played the second

oboe part. He never missed a note. [Both laugh] He

didn’t have to worry about the reed, and all this stuff. It was

in tune, and by golly there were times when I thought it was a real

oboe! The one thing I missed was the nuance. It was a

mechanical thing. I told the Japanese fellow about this and I

said, “It’s the one thing you haven’t done yet, and you’ll never be

able to do it! You can’t duplicate the human end of it.

That’s always going to be mechanical.” He said, “In what way?”

and I said, “Nuance. You can’t do this on your synthesizer

[sings]. You play [sings differently].” He said, “That’s

what you think. We already have it. We can do that.

We’ve already done it with the greatest singers. We recorded them

and then we put it on the synthesizer and followed it. We do it

by frequency. We add the frequency to it and it goes up, and we

reduce it and it comes up and down. You will never know the

difference.” That worried me. I said, “Oh, my God,

really? Why don’t you have it out?” He said, “Because we

have a fifty million dollar inventory we’ve got to sell.” He told

me the designs on the table were already in for the year 2000, and

they’re not like this 1991 model. They’ve got to sell the old

things first. Their plants are all set up for this and it would

cost millions of dollars to re-tool, to say nothing of the existing

inventory. They’ll sell the old ones out and then the new model

will come in. That’s gradual, as long as that inventory is

there. I learned a lot from that young man. So in response

to your question, I don’t think anyone can forecast this. Would

you believe fifteen years ago what’s happened in the CDs?

BD: Of course

not.

WR: Of course

not. The recording industry is about shot. Who buys records

now?

BD: Well, the

long-playing records are gone. The compact disks are current.

WR: Yeah, but

I’ve got an inventory of these. I don’t know what’s going to

happen to those. They’ll probably become collector’s items someday.

BD: We still

have the LPs and we still can play them on the radio, so I’ve got to

make sure we can always play those.

WR: But do

you think ten years from now you’ll be doing that?

BD: I hope so.

WR: But do

you think so?

BD:

[Shrugs] Flip a coin.

WR: Well,

that’s the same way with music. Will a symphony orchestra be

around in the year 2500? What’s it going to be? Where will

bands be? Where will education be? The one thing that the

band has is the appeal to the common man, and there are more common men

than there are uncommon men and women. Tonight the greatest

thrill to me was that audience. That was even greater than the

performance. I mean it. How many people were there?

Pretty close to two thousand, maybe more. It was a big crowd and

I watched it. When I conduct I watch. I look at the faces

and I saw what I wanted to see. I saw the smile. I saw the

receptivity. I saw the enjoyment. I saw the attitude of

receptivity and it was genuine. It wasn’t because it’s polite,

which some people do when they go to opera. That’s Americana, so

I have great faith in the future of the band. I think the destiny

of it lies in the hands of the conductors, not the players. The

players are there. There are thousands. About a half a

dozen came to me after the concert and said that they played in the

high school band and they’re still playing. Granted, the majority

of the students that graduate from universities never touch their

instruments again...

BD: ...but

hopefully, they come to concerts!

WR: That’s

another thing, and that’s encouraging.

|

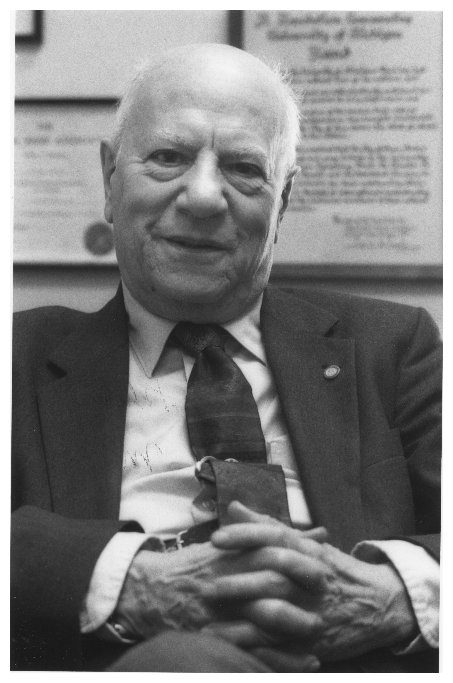

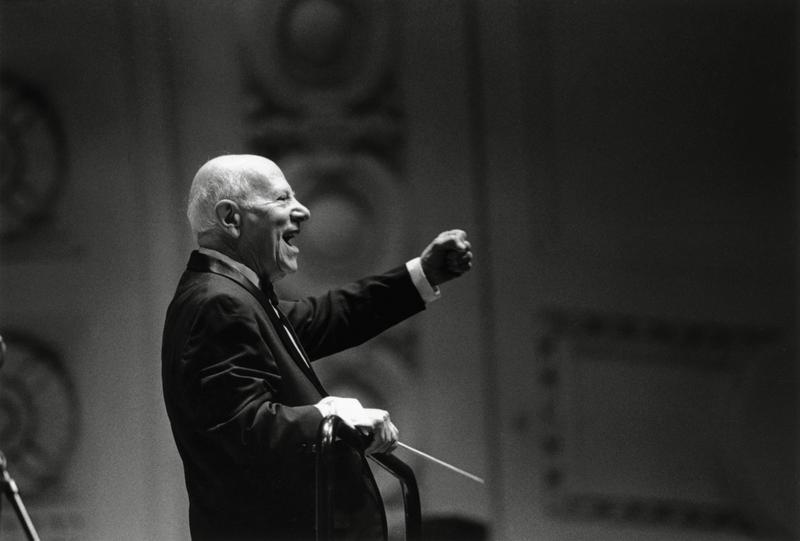

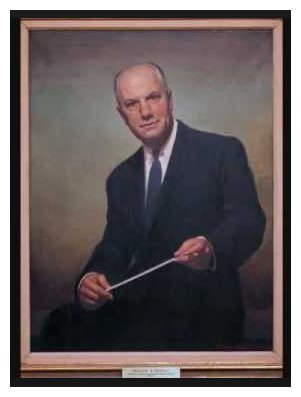

Legendary Band Leader William Revelli

July 20, 1994

By Knight-Ridder/Tribune.

[Text only - photo added]

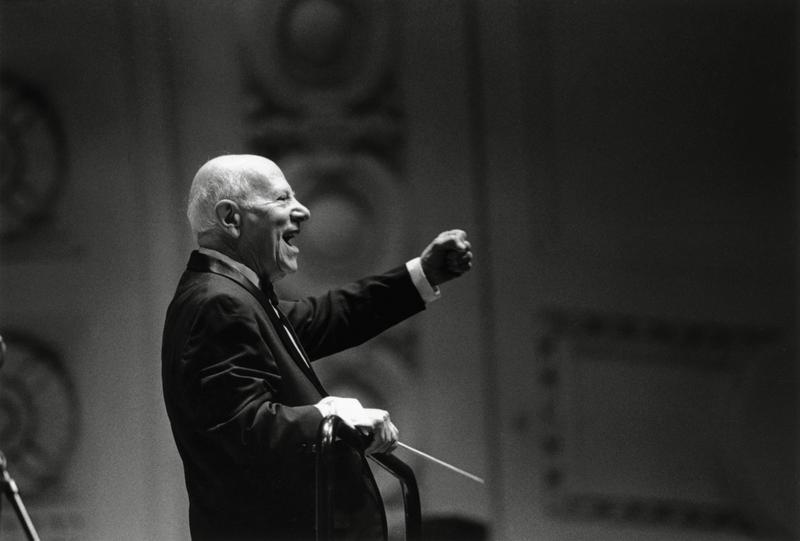

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — When the University of Michigan band marched under

William Revelli, the lines of musicians had to be straight and smart,

the music clear and sharp. Nothing but perfection was good enough.

Mr. Revelli's ability to accomplish that made him a legend in American

band music.

"It's very difficult to talk about Bill Revelli except

in

superlatives," said Allen Britton, dean emeritus of the Michigan School

of Music. "He developed the U-M bands into the best in the country.

Nothing ever sounded like a Revelli band except a Revelli band." "It's very difficult to talk about Bill Revelli except

in

superlatives," said Allen Britton, dean emeritus of the Michigan School

of Music. "He developed the U-M bands into the best in the country.

Nothing ever sounded like a Revelli band except a Revelli band."

Mr. Revelli, who retired in 1972 after 36 years as band director, died

of heart failure Saturday at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital near Ann Arbor.

He was 92.

He remained active on campus and accepted engagements as guest

conductor for bands around the world.

He was inducted into the National Band Association Hall of Fame of

distinguished conductors in 1981.

In 1989, the Louis Sudler Foundation and the John Philip Sousa

Foundation presented him with their Order of Merit.

He was a "Mt. Rushmore figure" in his field, said professor H. Robert

Reynolds, a former student who succeeded him as band director in 1975

and continues in the position.

"He was single-handedly responsible for raising the standards

everywhere," Reynolds said. "He had a popularity with the general

public that was unique, while he was highly respected by the band

profession. . . . He deserves to be remembered forever."

Mr. Revelli studied violin and music theory at the Beethoven

Conservatory of Music in St. Louis and later the Chicago Musical

College and the VanderCook School of Music in Chicago.

His drive for excellence showed early in his career, when he led the

band at Hobart (Ind.) High School to six national high school

championships from 1929 to 1935.

In 1935, he moved to Michigan as director of bands, including the

symphony band, with which he toured nationally.

In 1961, he led the symphony band on a 16-week international tour

sponsored by the U.S. State Department.

Survivors include two grandchildren, John Strong and Kimberly Snyder,

and two great-grandchildren.

|

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at

his hotel on August 1,

1991. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB in 1992 and 1997. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with

links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

During that time, one of the band

directors was a Michigan graduate,

and he persuaded his old mentor, William Revelli, to come and be the

guest conductor. Our director made it clear that we would not

really appreciate this special event until much later, and that turned

out to be the case. We played — presumably well — and continued with our lives and

families and careers in many fields. It was, indeed, a

great experience, but for us it was just another highlight. Only

in retrospect do we now understand that this was more. It was a

personal link to the wonder that is “The Band” in the very best sense.

During that time, one of the band

directors was a Michigan graduate,

and he persuaded his old mentor, William Revelli, to come and be the

guest conductor. Our director made it clear that we would not

really appreciate this special event until much later, and that turned

out to be the case. We played — presumably well — and continued with our lives and

families and careers in many fields. It was, indeed, a

great experience, but for us it was just another highlight. Only

in retrospect do we now understand that this was more. It was a

personal link to the wonder that is “The Band” in the very best sense. BD: Why do we

remember Sousa and not these others?

BD: Why do we

remember Sousa and not these others? BD: But there IS a

symphony, and there are chamber groups and opera companies, but no band!

BD: But there IS a

symphony, and there are chamber groups and opera companies, but no band! BD: Because of its

density?

BD: Because of its

density? WR: That’s a good

question, and the answer is that if the conductor is truly a serious

musician and he’s an educator, he will have both. There’s no

reason in the world that a football band has to play badly.

That’s the conductor’s responsibility. My men — and

women, later — in the Michigan marching band hated

my guts when I would work them hard before the last game of the

season. We’re playing on national television the next day and we

hadn’t been through the show once completely without stopping.

It’s snowing, it’s cold, it’s the last game and Revelli’s stopping that

band and tuning it and trying to get it together! They’re

frozen! They’re so cold, the valves are cold, their fingers are

cold, and Revelli’s saying, “The third cornet, let’s hear you.”

They said, “This guy’s impossible!” Then we would play and the

audience would receive us they way they did, and they were so

proud. They knew it was good. Then Revelli was okay, you

see. So that was that. There you are. I told them,

“The C-natural on your trumpet, half-note, forte, is no different; you

don’t read it any different, you don’t play it any differently than you

would if you were playing with the symphony at Carnegie Hall.”

You’ve got to approach it that way. You don’t just blow your

brains out on a gridiron because everybody’s up, up, up, rah, rah,

rah. I don’t go for that. The tone of my concert band and

the symphony band, at least the objective was not different. It

was educational all the way down the line. I know so many bands

just blow, you know. There’s no musicianship about it, not even

the intent at being musical.

WR: That’s a good

question, and the answer is that if the conductor is truly a serious

musician and he’s an educator, he will have both. There’s no

reason in the world that a football band has to play badly.

That’s the conductor’s responsibility. My men — and

women, later — in the Michigan marching band hated

my guts when I would work them hard before the last game of the

season. We’re playing on national television the next day and we

hadn’t been through the show once completely without stopping.

It’s snowing, it’s cold, it’s the last game and Revelli’s stopping that

band and tuning it and trying to get it together! They’re

frozen! They’re so cold, the valves are cold, their fingers are

cold, and Revelli’s saying, “The third cornet, let’s hear you.”

They said, “This guy’s impossible!” Then we would play and the

audience would receive us they way they did, and they were so

proud. They knew it was good. Then Revelli was okay, you

see. So that was that. There you are. I told them,

“The C-natural on your trumpet, half-note, forte, is no different; you

don’t read it any different, you don’t play it any differently than you

would if you were playing with the symphony at Carnegie Hall.”

You’ve got to approach it that way. You don’t just blow your

brains out on a gridiron because everybody’s up, up, up, rah, rah,

rah. I don’t go for that. The tone of my concert band and

the symphony band, at least the objective was not different. It

was educational all the way down the line. I know so many bands

just blow, you know. There’s no musicianship about it, not even

the intent at being musical. WR: I’m highly

optimistic about it. I have never been more thrilled and more

confident and overjoyed with what I see. I’m disappointed in many

things in the music education field, and in the bands in the schools I

am very disappointed, but more than ever in my life I’m convinced that

music education is here to stay. I have yet to see one program

that’s good where they have curtailed it. But we have so many

mediocre ones. We have so many that are so bad, unfortunately,

and they’re the ones that are in jeopardy. There’s too many of

them.

WR: I’m highly

optimistic about it. I have never been more thrilled and more

confident and overjoyed with what I see. I’m disappointed in many

things in the music education field, and in the bands in the schools I

am very disappointed, but more than ever in my life I’m convinced that

music education is here to stay. I have yet to see one program

that’s good where they have curtailed it. But we have so many

mediocre ones. We have so many that are so bad, unfortunately,

and they’re the ones that are in jeopardy. There’s too many of

them. "It's very difficult to talk about Bill Revelli except

in

superlatives," said Allen Britton, dean emeritus of the Michigan School

of Music. "He developed the U-M bands into the best in the country.

Nothing ever sounded like a Revelli band except a Revelli band."

"It's very difficult to talk about Bill Revelli except

in

superlatives," said Allen Britton, dean emeritus of the Michigan School

of Music. "He developed the U-M bands into the best in the country.

Nothing ever sounded like a Revelli band except a Revelli band."