BD: Does it get too

soggy in the

summertime?

BD: Does it get too

soggy in the

summertime? DR: Just as it

comes. Concerto performing for

guitar is always a small proportion of the concerts. I’ll

probably play five or six across the

summer, and maybe fifteen solo concerts. That’s about the

proportion, and this year it’s maybe a little more than some other

years. Basically it’s just as it fits in. I

don’t necessarily go out of my way to look for concertos. Playing

concertos is great fun for us because it’s different and we

don’t do it very often. Also, we get a chance to play for a

different audience. It’s not the same audience that goes to a

solo

concert, so it’s fun and I enjoy it. We do have a slight problem

because the classical guitar is a very quiet instrument, and we usually

have to amplify. Nowadays, the amplification is getting better

and better. The systems are better.

DR: Just as it

comes. Concerto performing for

guitar is always a small proportion of the concerts. I’ll

probably play five or six across the

summer, and maybe fifteen solo concerts. That’s about the

proportion, and this year it’s maybe a little more than some other

years. Basically it’s just as it fits in. I

don’t necessarily go out of my way to look for concertos. Playing

concertos is great fun for us because it’s different and we

don’t do it very often. Also, we get a chance to play for a

different audience. It’s not the same audience that goes to a

solo

concert, so it’s fun and I enjoy it. We do have a slight problem

because the classical guitar is a very quiet instrument, and we usually

have to amplify. Nowadays, the amplification is getting better

and better. The systems are better. DR: No, there are

not, really. I would

love to have another 10 concerti that are really good and

worth playing. There are a few composers who have written some

very good concerti recently, and the one that comes to mind is by Leo

Brouwer, a Cuban composer who is now working as a conductor in

Cordoba, Spain. Brouwer has written three or four concerti.

There are two of them I really like and that I think are

excellent. They’ve made the guitar sound good; the orchestra

sounds good, and all around it’s exciting to play. There

are quite a few pretty contemporary pieces, but we only get a chance to

play a few; Stephen Dodgson wrote a few concerti, and Lennox Berkeley,

and a few of the English composers. I’m sure in America

there are many that I wouldn’t know of. The problem is that we

may only get one booking in a year, or one

booking in five years, for some of these concerti. They’re very

difficult and take a lot of time to learn, so

it’d be unusual for me to actually learn one simply on the off chance

that one day I might get booked. But when I’m offered, I

pick. Usually they say, “Can you play the Rodrigo

concerto for us?” I say okay, I’ll be there.

When they say to me, “Take your choice,” next time

I’ll probably try and play one of the other Brouwer ones that I

haven’t done, or one of the concerti that are lesser known. As

far as the solo repertoire, there’s more than I’m ever going to be able

to learn in my years

of life and playing.

DR: No, there are

not, really. I would

love to have another 10 concerti that are really good and

worth playing. There are a few composers who have written some

very good concerti recently, and the one that comes to mind is by Leo

Brouwer, a Cuban composer who is now working as a conductor in

Cordoba, Spain. Brouwer has written three or four concerti.

There are two of them I really like and that I think are

excellent. They’ve made the guitar sound good; the orchestra

sounds good, and all around it’s exciting to play. There

are quite a few pretty contemporary pieces, but we only get a chance to

play a few; Stephen Dodgson wrote a few concerti, and Lennox Berkeley,

and a few of the English composers. I’m sure in America

there are many that I wouldn’t know of. The problem is that we

may only get one booking in a year, or one

booking in five years, for some of these concerti. They’re very

difficult and take a lot of time to learn, so

it’d be unusual for me to actually learn one simply on the off chance

that one day I might get booked. But when I’m offered, I

pick. Usually they say, “Can you play the Rodrigo

concerto for us?” I say okay, I’ll be there.

When they say to me, “Take your choice,” next time

I’ll probably try and play one of the other Brouwer ones that I

haven’t done, or one of the concerti that are lesser known. As

far as the solo repertoire, there’s more than I’m ever going to be able

to learn in my years

of life and playing. DR: Yeah there is,

in a sense that up until this

century, most of the guitar music was written by guitarists and most

of lute music was written by lutenists, with a few

exceptions, of course. Most people who play the

instrument are caught, in that they will only write what they can

play because

most of them are writing it for themselves. So unless they were

really agile players, I mean technically, they wouldn’t necessarily

demand enough out of their instrument. And a lot of them would

often get caught into a little thing of writing tricks. There are

certain little finger patterns that actually sound great, but

we all know it’s really easy. So these little idioms start to

creep

in. Of course that happens in all instruments, and it’s normal

that that’s going to happen. But most of that music is actually

designed to make the guitar sound good, and maybe to let the

guitarist show off a certain amount. A lot of it has more of the

virtuoso quality — like Paganini violin music. Well, Paganini

also wrote

guitar music — not to such a high level, because he wasn’t as good a

guitarist — but in the similar vein. Giuliani was another

composer of that period who wrote, basically, to show off what he could

do.

Sor was slightly different in that he was a more developed musician,

and maybe not quite such an agile player. So he got more out of

the instrument, musically, by use of harmony,

than just purely showing how fast his fingers would go. Perhaps

at the beginning of the century or end of

last century, it was easier to do a transcription because the

transcriber would take complete liberty of the

piece. He would actually rewrite bits and expand bits to make

them sound

more interesting, and just reduce other bits to give a

general view of this section of whatever. They usually called

it “Fantasies on,” rather than a transcription exactly.

Nowadays when we do transcriptions, because of the tradition or because

of whatever way it’s developed, we try to play as close as the original

would have been.

DR: Yeah there is,

in a sense that up until this

century, most of the guitar music was written by guitarists and most

of lute music was written by lutenists, with a few

exceptions, of course. Most people who play the

instrument are caught, in that they will only write what they can

play because

most of them are writing it for themselves. So unless they were

really agile players, I mean technically, they wouldn’t necessarily

demand enough out of their instrument. And a lot of them would

often get caught into a little thing of writing tricks. There are

certain little finger patterns that actually sound great, but

we all know it’s really easy. So these little idioms start to

creep

in. Of course that happens in all instruments, and it’s normal

that that’s going to happen. But most of that music is actually

designed to make the guitar sound good, and maybe to let the

guitarist show off a certain amount. A lot of it has more of the

virtuoso quality — like Paganini violin music. Well, Paganini

also wrote

guitar music — not to such a high level, because he wasn’t as good a

guitarist — but in the similar vein. Giuliani was another

composer of that period who wrote, basically, to show off what he could

do.

Sor was slightly different in that he was a more developed musician,

and maybe not quite such an agile player. So he got more out of

the instrument, musically, by use of harmony,

than just purely showing how fast his fingers would go. Perhaps

at the beginning of the century or end of

last century, it was easier to do a transcription because the

transcriber would take complete liberty of the

piece. He would actually rewrite bits and expand bits to make

them sound

more interesting, and just reduce other bits to give a

general view of this section of whatever. They usually called

it “Fantasies on,” rather than a transcription exactly.

Nowadays when we do transcriptions, because of the tradition or because

of whatever way it’s developed, we try to play as close as the original

would have been.  DR: There’s a

certain

difference. I try really hard to make the recording sound as

exciting as I hope it will in a concert. But certainly there are

certain

differences. The perfection now required in

recording has reached such a high level, and the guitar is a very noisy

instrument. We play at a low decibel level, so our

finger noise is pretty close to our music noise — little

string scratches and squeaks and fingernails

clacking means that we have to play extra carefully. We have to

play extra clean because the digital process picks up so much

nowadays! You can’t just filter it because if

you filter it, you lose everything. Usually there’s

a certain kind of reserve in the recording at first, and hopefully I’m

able to break away from it after I’ve got a few good takes. All

recordings are

stressful sort of situations, but without the excitement of a

audience. The only person you’re

going to try and excite is your engineer, and maybe your

producer.

DR: There’s a

certain

difference. I try really hard to make the recording sound as

exciting as I hope it will in a concert. But certainly there are

certain

differences. The perfection now required in

recording has reached such a high level, and the guitar is a very noisy

instrument. We play at a low decibel level, so our

finger noise is pretty close to our music noise — little

string scratches and squeaks and fingernails

clacking means that we have to play extra carefully. We have to

play extra clean because the digital process picks up so much

nowadays! You can’t just filter it because if

you filter it, you lose everything. Usually there’s

a certain kind of reserve in the recording at first, and hopefully I’m

able to break away from it after I’ve got a few good takes. All

recordings are

stressful sort of situations, but without the excitement of a

audience. The only person you’re

going to try and excite is your engineer, and maybe your

producer.  BD: Do you have any

advice for

younger guitarists coming along?

BD: Do you have any

advice for

younger guitarists coming along?|

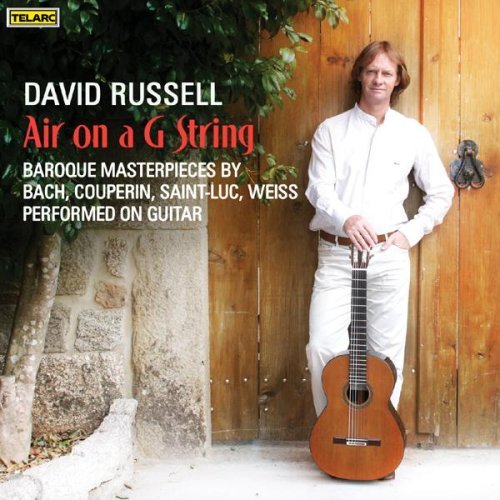

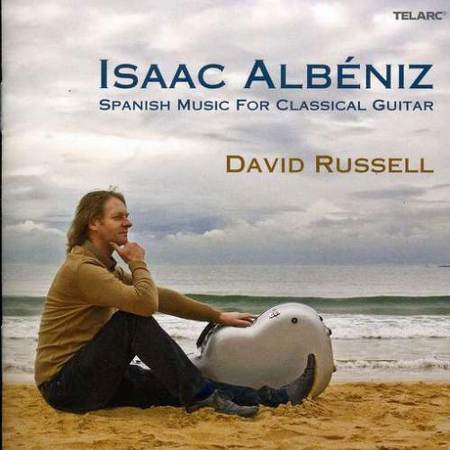

David Russell

Born: 1953 - Glasgow, Scotland, UK The Scottish guitarist, David Russell, was born in Glasgow, and while still very young (age 5), moved with his parents to Menorca, a Spanish island in the Mediterranean. His father, an artist, was an avid amateur guitarist. It became natural for David to pick up the instrument, and his father began to teach him to play it. He cannot remember when he did not play the guitar. Before he could read music, he could play the pieces by ear that he had learned from listening to Andrés Segovia recordings. When he got somewhat older he also learned to play violin and French horn.  David Russell returned to Britain at the age of 16 to

attend the Royal Academy of Music in London. There his primary teacher

was Hector Quine. He also continued to study horn and violin. While

studying, he twice won the Julian Bream Prize in guitar. He graduated

in 1974 with a Ralph Vaughan Williams Trust Scholarship. In 1975, the

Spanish Government granted him a special grant to enable him to return

to Spain and continue his studies with José Tomás in

Santiago de Compostela. In the next few years, he won the major Spanish

guitar prizes - the José Ramírez Competition of Santiago

de Compostela in 1975, the Andrés Segovia Prize of Palma de

Mallorca in 1977, the Alicante Prize, and the most prestigious of all,

Spain's Francisco Tárrega Competition. David Russell returned to Britain at the age of 16 to

attend the Royal Academy of Music in London. There his primary teacher

was Hector Quine. He also continued to study horn and violin. While

studying, he twice won the Julian Bream Prize in guitar. He graduated

in 1974 with a Ralph Vaughan Williams Trust Scholarship. In 1975, the

Spanish Government granted him a special grant to enable him to return

to Spain and continue his studies with José Tomás in

Santiago de Compostela. In the next few years, he won the major Spanish

guitar prizes - the José Ramírez Competition of Santiago

de Compostela in 1975, the Andrés Segovia Prize of Palma de

Mallorca in 1977, the Alicante Prize, and the most prestigious of all,

Spain's Francisco Tárrega Competition.David Russell made his Wigmore Hall (London) and New York debuts in the same year, 1981, and has since performed and recorded widely in concerts, recitals and music festivals. He has performed in the major concert venues of the world in North (New York, Los Angeles, Toronto) and South America, Asia (Tokyo), Australia, and Europe (London, Madrid, Rome). David Russell is an exceptional classical guitarist, known for an attractive and outgoing stage presence. He is world renowned for his superb musicianship and inspired artistry, which have earned the highest praise from audiences and critics alike. He is noted for including new or unfamiliar music in most of his recitals. An often-mentioned attribute of his playing is his command over a wide variety of tone colour. His love of his craft resonates through his flawless and seemingly effortless performance. The attention to detail and provocative lyrical phrasing suggest an innate understanding of what each individual composer was working to achieve, bringing to each piece a sense of adventure. Composers who have written music for him include Jorge Morel, Francis Kleynijans, Carlo Domeniconi, Sergio Assad, and Guido Santorsola. His qualities carrie over into his frequent stints as a teacher of master-classes, for which he is much in demand. David Russell has recorded primarily for the GHA and Telarc Records labels, and on Opera Tres, he recorded the complete works of Francisco Tarrega. Since 1995 he has an exclusive recording contract with Telarc International, with whom he has recorded 12 CD's up to now, among them Aire Latino, which received a grammy in 2005. He has made recordings of several works of the Paraguayan composer Agustín Barrios Mangoré and Spanish composer Federico Moreno-Torroba and a release comprising the three solo guitar concerted works of Joaquín Rodrigo: Concierto de Aranjuéz, Fantasía para un Gentilhombre, and Concierto para una Fiesta. In recognition of his great talent and his international career, David Russell was named a Fellow of The Royal Academy of Music in London in 1997. In May 2003 he was bestowed the great honor of being made "adopted son" of Es Migjorn, the town in Minorca where he grew up. Later the town named a street after him, "Avinguda David Russell". In November 2003 he was given the Medal of Honor of the Conservatory of the Balearics. In 2005 he was GRAMMY award winner for his CD Aire Latino, in the category of best instrumental soloist in classical music. After winning the grammy award, the town of Nigrán in Spain where he resides, gave him the silver medal of the town in an emotional ceremony. In May 2005 he received an homage from the music conservatory of Vigo, culminating with the opening of the new Auditorium, to which they gave the name "Auditorio David Russell". |

This interview was recorded at his hotel on June

20, 1996. It

was used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1998, and on WNUR in 2006.

It was transcribed and posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.