Presenting

RENATA

SCOTTO

By Bruce Duffie

[Note: When this interview took place in 1988, I knew it would be

published in The Massenet Newsletter, as well as have its

usual airings on WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago. This is why there

is a particular emphasis on French opera in addition to the general

questions about her career and her views on singing, etc. What

follows is the material that was published July of 1991, with the

addition of a few small sections which were cut in that presentation,

and photographs which have been found on the internet.]

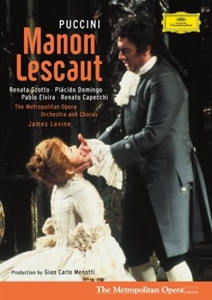

Even though her name evokes many of the great verismo Italian operas,

Renata Scotto has done a number of French roles, including Manon as

early as 1963, and more recently Charlotte.

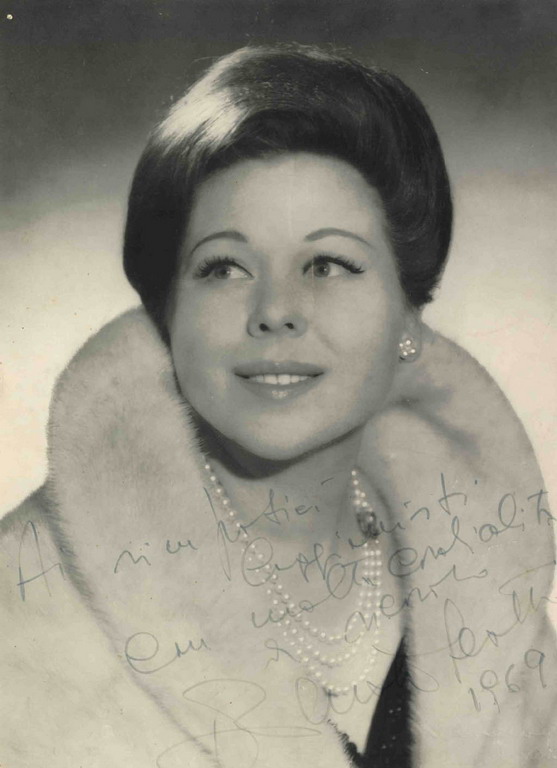

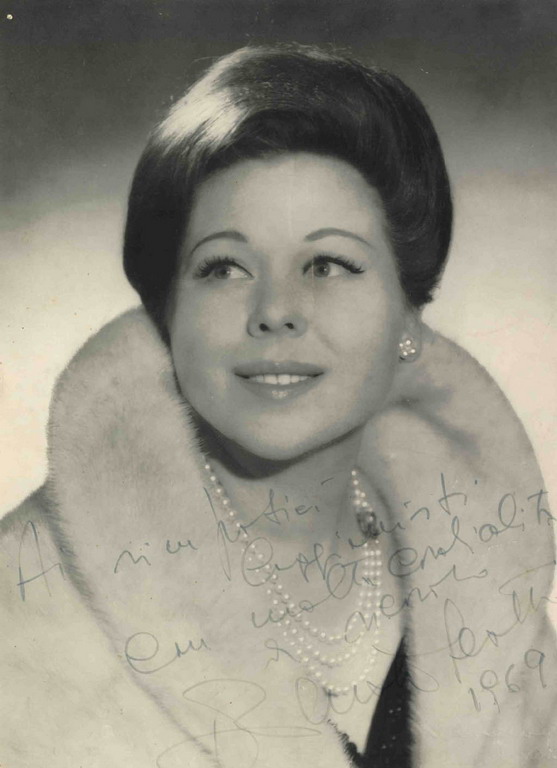

Born in 1934, Scotto studied in Milan and made her debut

at the Teatro

Nuovo when she was only 19. Immediately engaged by La Scala, she

has appeared there and in many other opera houses around the world

regularly ever since. It was in 1957 that she stepped in for

Callas and made a name for herself by not disappointing those who had

come to hear the reigning diva.

Born in 1934, Scotto studied in Milan and made her debut

at the Teatro

Nuovo when she was only 19. Immediately engaged by La Scala, she

has appeared there and in many other opera houses around the world

regularly ever since. It was in 1957 that she stepped in for

Callas and made a name for herself by not disappointing those who had

come to hear the reigning diva.

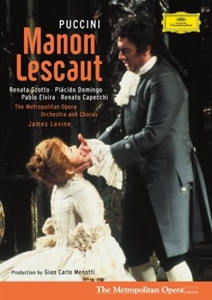

In this country, she has been heard at the Met many times since 1965,

and has been seen on several “Live from the Met” telecasts including

the very first one of the current series. But it was in Chicago

that she made her American debut in 1960, and she has sung here several

times since in various operas, including Manon with Alfredo Kraus.

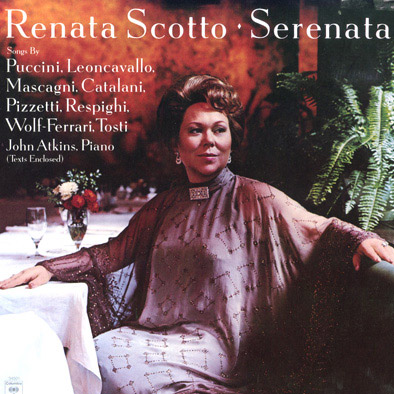

Besides her opera and concert appearances, Scotto has made many

recordings, two on the Hungaroton label (HCD 31037 and HCD 31116) being

of special interest since they contain French repertoire. She has

also recorded many of her roles complete on various labels over the

years.

It was during a visit to Chicago in 1988 that I had the opportunity to

meet with Miss Scotto at her apartment between performances of

Tosca. She was kind and

gracious, and delighted in showing me her

current project – designing costumes for upcoming productions.

Her English was quite good, though it occasionally frustrated her not

to be able to speak as quickly and as easily as she was obviously

thinking.

Here, then, is much of what was said that afternoon.....

Renata Scotto: My dream

and desire is to design costumes.

In my Butterfly in Verona, I

did design my own costumes. I have

to improve my study, so I have books on fabrics and period styles all

over.

Bruce Duffie: Will you do

set design also, or just costumes?

RS: No, just costumes,

and staging which I did already and liked

very much.

BD: I’m impressed that a

singer with your experience would want

to share some of that with others and bring it to life elsewhere.

RS: I like it very much,

but I have to study because it’s a

completely different perspective. You have to forget that you are

a singer.

BD: Have you done both at

the same time?

RS: The first time I was

also in the production; later, I was the

only director.

BD: Which is better?

RS: When you’re

directing, it’s better not to also sing.

It’s very difficult to do both, and I like to direct and I like to

sing. But it should be two separate people. In my directing

debut at the Met, I also sang. In Verona, I also sang, but only

the last two performances. The show was already running for 8

performances before I stepped onstage to sing in my staging.

BD: Tell me about the

secret of singing Puccini.

RS: Oh my god. There’s no

secret as long as you can sing

what Puccini wrote. Often, I see young people who start their career

with Puccini because they think it’s easier than other composers like

Verdi. If you take the score only (just the notes), of course

it’s easier. Verdi, and other composers of the romantic 19th

century, need bel canto technique. So, when I see the young

people sing Puccini, I know they’re making a big mistake. In

order to sing Puccini, you have to know how to sing first. You

have to know the meaning of being a singer who knows how to act and

make a character believable. That is the great secret of Puccini

– theater, words in music, but in the verismo style. Many times

“verismo” is misunderstood and they think “melodrama” is the same

thing. Verismo is a style, like bel canto. Verdi is his own

style, as is Wagner. Verismo includes many composers from the

late 19th to early 20th centuries. From my experience and

study, verismo is a very precise style where everything is

concentrated, and there are only a few pages of music to express a

situation either dramatic or comic. The structure is different –

fewer recitatives or duets and trios. They are there, but they

are concentrated.

RS: Oh my god. There’s no

secret as long as you can sing

what Puccini wrote. Often, I see young people who start their career

with Puccini because they think it’s easier than other composers like

Verdi. If you take the score only (just the notes), of course

it’s easier. Verdi, and other composers of the romantic 19th

century, need bel canto technique. So, when I see the young

people sing Puccini, I know they’re making a big mistake. In

order to sing Puccini, you have to know how to sing first. You

have to know the meaning of being a singer who knows how to act and

make a character believable. That is the great secret of Puccini

– theater, words in music, but in the verismo style. Many times

“verismo” is misunderstood and they think “melodrama” is the same

thing. Verismo is a style, like bel canto. Verdi is his own

style, as is Wagner. Verismo includes many composers from the

late 19th to early 20th centuries. From my experience and

study, verismo is a very precise style where everything is

concentrated, and there are only a few pages of music to express a

situation either dramatic or comic. The structure is different –

fewer recitatives or duets and trios. They are there, but they

are concentrated.

BD: Was Puccini the

supreme example of the verismo style?

RS: I would say that it

didn’t begin with Puccini. We could

speak of Ponchielli, and then we’re back in the 19th century. The

verismo is drama in music. You do not have the long recitatives

to explain the situation followed by an aria with a cadenza. The

beginning of verismo is in the

late Verdi, like Otello and Falstaff. Verdi for me is the

greatest opera composer, the same as Wagner. I don’t do Wagner so

I don’t know much of his music even though I love it. I’m crazy

about it, but I need to

sing it in order to know it, so I cannot. But the

difference between the early Verdi of 1844-1848 and late Verdi toward

the end of the century is immense. There is

a line from the beginning to the end.

BD: You sing both Verdi

and Puccini. What are the differences in the vocal style?

RS: For Verdi, you need a

special technique because you have everything. He is very

much a demanding composer from the point of view of the singer.

He wrote

for the voice, but asked everything from the voice.

BD: Did he ever ask too

much?

RS: [In a matter-of-fact

tone] No. No, not too much. Verdi is just perfect. He

only

demands a good singer, which is a lot! You have to study

very much to sing Verdi. You have coloratura, you have legato and

legatissimo, pianissimi, fortissimi, parole – words. Every

character is

different, and even if the music looks alike, the difference is

great. I sang a lot of Verdi, and the difference between Gilda in

Rigoletto and Violetta in La Traviata, which is already a

dramatic character, or even Lady Macbeth or Elena in I Vespri Siciliani, is in the drama

because the music looks almost the same. It has coloratura,

dramatic moments, legati, high notes, low notes, everything is

there. It depends on the character – the right

expression, the right words. He requires more voice, more

temperament. Gilda is a young and inexperienced woman

and you have to keep this shape to the character.

BD: Did Verdi put all of

this into his music, or did he expect you to bring this understanding

of each character?

RS: He puts everything

into the music, but it’s up to you to

understand. He wrote everything, but not everything that he wrote

is understood. When a writer pens a book, sometimes you

misunderatand what he is trying to say, or perhaps you don’t

see it.

BD: Is that the beauty of

Verdi – that you can keep discovering things for years?

RS: For everything, not

only for Verdi but especially his music. Violetta is one of the

roles that I sang most in twenty years of my career and each time I

found something not different but to undertand better. That is a

very difficult role because musically it is very sophisticated, but not

in the orchestra. He leaves everything to the singer to phrase

the meaning of the words, to find what is underneath the

character. When she meets Alfredo in the first act, she thinks he

is just one of the many men she has met. But when she is alone

and she thinks about him, something goes on in her mind. The way

he was talking about her makes her think that maybe this was the man

she was waiting for. In the first part of her aria, there are

some words which are very sad. I thought about that a lot and had

a feeling she wanted much, much more. She knows that it will

change her life. She was very sad and knows she is sick, and is

waiting for this big change. In the music you have everything so

those words have different meanings if you think about it. It

is not superficial. Nothing is superficial in Verdi, especially

for Violetta in the first act. So there is always something

special.

BD: When you portray

Violetta, does this woman, living in the

remote past still speak to women (and men) at the end of the 20th

century?

RS: The romantic period

had its own style, which is absolutely

different than the style today. At that time, in order to meet a

man and say, “I love you” would take much longer than it would take

today in the modern way when everything is fast. One of the

beauties of romanticism is its slow pace. If you want to talk

about romanticism, Massenet, in some of his operas shows the real

romantic period. To have them kiss each other in Werther you

wait three hours, and to die takes 20 minutes! This is

romantic. I’m a romantic and I like romanticism, but it doesn’t

go with our life, even though I feel the modern audiences love to see

it on the stage. They cannot have it in their lives, so they go

into the theater to identify with some character. For two hours,

you go into another world.

BD: Does it change their

lives completely?

RS: I think so. It

changes mine when I’m onstage, and I

believe I change the life of my audience – at least for two hours.

BD: Well, where is the

balance between an artistic achievement

and an entertainment value?

RS: From my side, the

artistic achievement is to be able to take

the audience away from their outside life. To understand the

artistry of the composer and of the theater, and to be able to transfer

this from me to the audience is the achievement I’m waiting for every

time I

step onstage. I know I’m there to entertain. Hopefully, I’m

not only an entertainer.

*

* *

* *

BD: Let’s stay with

Massenet for a bit. How are his operas

written differently for the voice from Puccini or Verdi?

RS: I believe that

Massenet is the Puccini of the French. I

say that because in the same way, he brings life onstage to the

character and romanticism of verismo. He likes theater very much,

but in a different way. Puccini brings the Italian temperament

and Massenet brings the French temperament, which is more

sophisticated. As a woman, I like fashion and design very much,

and the French have a more soft taste in what concerns color and

design, even perfume.

BD: More delicate?

RS: Not delicate, but

more suave. Massenet is not always

delicate. The St. Sulpice duet in Manon is not delicate. It

is very forceful, very dramatic. The Puccini setting of the Manon

story is temperamental and passionate. Massenet is also

passionate, but different. It’s French passion. On the

other hand, the “Dream” is delicate but not superficial.

Delicacy can be profound. All this, of course, is only my opinion…

BD: But it’s what you

have discovered in singing the music.

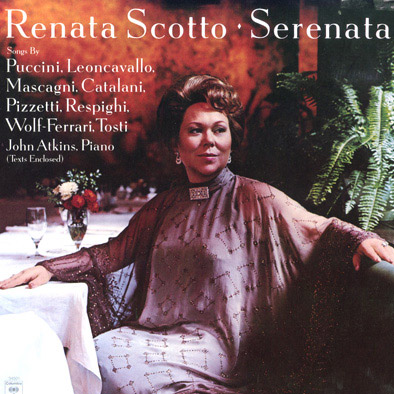

RS: I made a recording of French music –

mostly Massenet – and

included an aria from Sappho.

It’s a beautiful aria, and the

story has nothing to do with the mythological character. It’s a

love story. The man discovers that she posed nude for a

sculpture, and he’s very jealous. It’s a beautiful story. I

put the aria in the record and it’s fabulous. It’s quite close to

what Puccini would have liked to write about this passionate woman who

asks him to give her back the love he once felt. She wants him

back, and the aria is very much like Puccini, but in the French

style. Massenet is fascinating, and I love it. I’m a

Massenet fan. I discovered, when I sang Werther, how beautiful

Charlotte is and how deep the character is. I have also another

dream. It’s impossible, but I would love to sing in one day both

the Massenet and Puccini Manon! The two together make the

Prévost. What happens in one doesn’t happen in the other.

RS: I made a recording of French music –

mostly Massenet – and

included an aria from Sappho.

It’s a beautiful aria, and the

story has nothing to do with the mythological character. It’s a

love story. The man discovers that she posed nude for a

sculpture, and he’s very jealous. It’s a beautiful story. I

put the aria in the record and it’s fabulous. It’s quite close to

what Puccini would have liked to write about this passionate woman who

asks him to give her back the love he once felt. She wants him

back, and the aria is very much like Puccini, but in the French

style. Massenet is fascinating, and I love it. I’m a

Massenet fan. I discovered, when I sang Werther, how beautiful

Charlotte is and how deep the character is. I have also another

dream. It’s impossible, but I would love to sing in one day both

the Massenet and Puccini Manon! The two together make the

Prévost. What happens in one doesn’t happen in the other.

BD: Tell me about

Manon. Is she the original liberated woman?

RS: Yes... Well, it

depends on what you mean by

“liberated.” If you mean that she has to work for her money and

pay for her own life, no. Manon wants the man to pay all the

time. If you mean that she does what she wants all the time, then

yes she is liberated. Today, liberation for women means

that they have to work twice – the domestic chores in the home and a

job outside! Manon is very selfish. She needs a man and

needs everything, and she pays for it emotionally. I think there

is a little bit of Manon in every woman. Many women won’t say so,

but I think it’s true.

BD: If Manon were around

today, might she have stayed with Des

Grieux but gone out and gotten a job to help support their lifestyle?

RS: [Quietly giggling] I

don’t think so. She’d still change

men and find a rich one!

BD: Well, would Manon

have been happier if she’d gone off with

the rich man first without ever meeting Des Grieux?

RS: Mmmm, no.

Everything that she does is what comes at the

moment. We see this young girl who has been sent away from home

to the convent because she was a bad girl. She finds a way to

avoid the convent.

BD: So even before we

meet her, she’s already been in trouble.

RS: Oh yes, of

course. She was one of those girls.

It’s a very modern story but you cannot live that way. The

girl always pays in the end. A girl like that today would finish

like Manon. It’s tragic. In life you have to think and do

the best you can to make your life good for yourself first. I’m a

mother and I’m very organized. When you have respect for

yourself, you have respect for others. Respect is what your life

is about.

BD: So the opera is

essentially a morality play.

RS: Yes. It

instructs you what can happen and how you can

end up.

BD: Then is Charlotte the

complete opposite of Manon?

RS: Yes. Charlotte

is in charge of her life, and we can

blame the society which makes you do things you don’t want to do.

Charlotte was not free to do what she wanted – not

because of her,

but because of her society. Manon didn’t care a bit about

society, but Charlotte was forced by her bourgeoisie family and her

education and her small town, and her very strong religion.

Society can change your life. You have to be in charge, and know

what you want to do, and not be forced by others, like in the case of

Charlotte, to marry whom they tell you.

BD: If Werther hadn’t

come into her life, would Charlotte have

been quietly happy with Albert?

RS: Who

knows? Maybe not.

BD: If she hadn’t been

forced to marry Albert, might she have

been happy with Werther?

RS: It is my belief from

what I’ve read that Werther would never

be happy. He has to be unhappy in order to be happy. He’s

that kind of character.

*

* *

* *

BD: Do you sing

differently in the recording studio that you do

in the theater?

RS: No, I don’t sing

differently. The only thing is that

when I do a recording, I have a much, much larger audience. A

record is a document and it’s forever. People, audiences,

students can go to it to understand or to listen or to compare.

So when I do a recording, I am very careful and do it knowing that I

have an audience of millions and millions of people. I like to

do, if I can, long takes. Each scene once, twice, maybe three

times until I like it. But not piece by piece or note by

note. That’s fake. You lose the spontaneity and stage

presence and the drama. So, when I’m in front of the microphone,

I try to picture the audience, and often it works. I am often

asked which are my favorites…

RS: No, I don’t sing

differently. The only thing is that

when I do a recording, I have a much, much larger audience. A

record is a document and it’s forever. People, audiences,

students can go to it to understand or to listen or to compare.

So when I do a recording, I am very careful and do it knowing that I

have an audience of millions and millions of people. I like to

do, if I can, long takes. Each scene once, twice, maybe three

times until I like it. But not piece by piece or note by

note. That’s fake. You lose the spontaneity and stage

presence and the drama. So, when I’m in front of the microphone,

I try to picture the audience, and often it works. I am often

asked which are my favorites…

BD: ...but I don’t ask

that question! However, let me ask a more general

question: are you basically pleased with those recordings you

have

made?

RS: Basically, yes.

BD: Do you ever feel

you’re competing onstage with the recordings

you have made of that role?

RS: Oh yes, oh yes.

When I make a record I think about the

audience, so in performance I have to think about the record because I

want to do the same performance.

BD: The same – or better?

RS: Same, better, worse,

whatever. It’s a performance.

BD: When you’re preparing

these roles, do you dig as much as you

can into the characters and the background of the work?

RS: Absolutely.

This is the first homework you have to

do. For me, first I have to know why the composer thought about

writing an opera about this character. If there is a play or

book, I read it. Then I go to the composers’ letters. I’m

so glad that they used to write letters so we can read them. I’m

not sure composers write so much any more. By reading them, you

can understand what the composer was thinking before he even starts the

first note. The choice of librettist was often forced upon the

composer by the publisher. Sometimes the subject was a

historical event that really happened, so you read about it. I

like to do the homework before I start learning the music, so when I

come to the music I know what I’m going to be dealing with, and I put

myself into it.

BD: When you’re offered

roles, how do you decide which ones

you’ll learn and which ones you’ll turn aside?

RS: When that happens, I

look immediately at the music. I

sing through it and sometimes I know immediately it’s not for

me. Other times, I have to do a bit of research. I also ask

maestri for advice, but you must be careful. Sometimes they see

the singers all the same. One soprano will be different from

another soprano. All will be different. Once, a maestro

told me not to do a certain role, but I did, and it became one of my

greatest parts. I judge for myself, but I need advice.

BD: What advice do you

have for young singers coming along?

RS: That is always a very

difficult question. Everyone must

gain their own experience. You can tell youngsters many things,

but until they experience things for themselves, they never

learn. So I encourage them to start as soon as possible because

they have a lot of time ahead to make mistakes. We have a saying

in Italian that translates, “By making mistakes, you learn.”

RS: That is always a very

difficult question. Everyone must

gain their own experience. You can tell youngsters many things,

but until they experience things for themselves, they never

learn. So I encourage them to start as soon as possible because

they have a lot of time ahead to make mistakes. We have a saying

in Italian that translates, “By making mistakes, you learn.”

BD: Is singing fun?

RS: Ah, yes! Yes

singing is fun! I always enjoy

singing very much. The moment before you go onstage is the most

terrible moment. A thousand things come into your mind. You

need to be able to go out and please an audience. You need to do

what you’ve been studying. You have so many questions in your

mind before you go out, and then you start. As soon as I start, I

enjoy it very much. It’s like I have a second life. Every

morning when I wake up, I thank God that he has given me this

gift. It is something special and it’s something that is not

mine. It’s for people who share with me, and for one or two or

three hours we share the same joy that I’ve found in this gift.

It makes me so happy and I hope that I can make others be happy, too.

BD: Is there any role

that you especially identify with?

RS: In every role there

is a moment that you identify with.

I don’t identify with Lady Macbeth… [laughter] But there is always a

moment that I identify with – as a woman, as a lover, as a

mother. There are many moments. When you go into a

style like the Bel Canto style or the Romantic style, it’s harder to

find the identification. But even there, there is always one

phrase that takes you back to yourself. Even with Manon!

[laughter] As I said, every woman has a little bit of Manon in

her!

=== === ===

=== ===

--- --- ---

=== === === === ===

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in Chicago on January 21,

1988. Portions were used on WNIB

(along with musical examples) in 1989, 1991, twice in 1994, and once

again 1999. A short segment was given to Lyric Opera of Chicago

and used on their website as part of their group of Jubilarians to celebrate the

50th anniversary season of the company in 2004. The

transcription was made in 1991 and published in The Massenet Newsletter in July of

that year; it was re-edited and posted on this website in November of

2008 with the addition of photographs.

Award-winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Born in 1934, Scotto studied in Milan and made her debut

at the Teatro

Nuovo when she was only 19. Immediately engaged by La Scala, she

has appeared there and in many other opera houses around the world

regularly ever since. It was in 1957 that she stepped in for

Callas and made a name for herself by not disappointing those who had

come to hear the reigning diva.

Born in 1934, Scotto studied in Milan and made her debut

at the Teatro

Nuovo when she was only 19. Immediately engaged by La Scala, she

has appeared there and in many other opera houses around the world

regularly ever since. It was in 1957 that she stepped in for

Callas and made a name for herself by not disappointing those who had

come to hear the reigning diva. RS: Oh my god. There’s no

secret as long as you can sing

what Puccini wrote. Often, I see young people who start their career

with Puccini because they think it’s easier than other composers like

Verdi. If you take the score only (just the notes), of course

it’s easier. Verdi, and other composers of the romantic 19th

century, need bel canto technique. So, when I see the young

people sing Puccini, I know they’re making a big mistake. In

order to sing Puccini, you have to know how to sing first. You

have to know the meaning of being a singer who knows how to act and

make a character believable. That is the great secret of Puccini

– theater, words in music, but in the verismo style. Many times

“verismo” is misunderstood and they think “melodrama” is the same

thing. Verismo is a style, like bel canto. Verdi is his own

style, as is Wagner. Verismo includes many composers from the

late 19th to early 20th centuries. From my experience and

study, verismo is a very precise style where everything is

concentrated, and there are only a few pages of music to express a

situation either dramatic or comic. The structure is different –

fewer recitatives or duets and trios. They are there, but they

are concentrated.

RS: Oh my god. There’s no

secret as long as you can sing

what Puccini wrote. Often, I see young people who start their career

with Puccini because they think it’s easier than other composers like

Verdi. If you take the score only (just the notes), of course

it’s easier. Verdi, and other composers of the romantic 19th

century, need bel canto technique. So, when I see the young

people sing Puccini, I know they’re making a big mistake. In

order to sing Puccini, you have to know how to sing first. You

have to know the meaning of being a singer who knows how to act and

make a character believable. That is the great secret of Puccini

– theater, words in music, but in the verismo style. Many times

“verismo” is misunderstood and they think “melodrama” is the same

thing. Verismo is a style, like bel canto. Verdi is his own

style, as is Wagner. Verismo includes many composers from the

late 19th to early 20th centuries. From my experience and

study, verismo is a very precise style where everything is

concentrated, and there are only a few pages of music to express a

situation either dramatic or comic. The structure is different –

fewer recitatives or duets and trios. They are there, but they

are concentrated. RS: I made a recording of French music –

mostly Massenet – and

included an aria from Sappho.

It’s a beautiful aria, and the

story has nothing to do with the mythological character. It’s a

love story. The man discovers that she posed nude for a

sculpture, and he’s very jealous. It’s a beautiful story. I

put the aria in the record and it’s fabulous. It’s quite close to

what Puccini would have liked to write about this passionate woman who

asks him to give her back the love he once felt. She wants him

back, and the aria is very much like Puccini, but in the French

style. Massenet is fascinating, and I love it. I’m a

Massenet fan. I discovered, when I sang Werther, how beautiful

Charlotte is and how deep the character is. I have also another

dream. It’s impossible, but I would love to sing in one day both

the Massenet and Puccini Manon! The two together make the

Prévost. What happens in one doesn’t happen in the other.

RS: I made a recording of French music –

mostly Massenet – and

included an aria from Sappho.

It’s a beautiful aria, and the

story has nothing to do with the mythological character. It’s a

love story. The man discovers that she posed nude for a

sculpture, and he’s very jealous. It’s a beautiful story. I

put the aria in the record and it’s fabulous. It’s quite close to

what Puccini would have liked to write about this passionate woman who

asks him to give her back the love he once felt. She wants him

back, and the aria is very much like Puccini, but in the French

style. Massenet is fascinating, and I love it. I’m a

Massenet fan. I discovered, when I sang Werther, how beautiful

Charlotte is and how deep the character is. I have also another

dream. It’s impossible, but I would love to sing in one day both

the Massenet and Puccini Manon! The two together make the

Prévost. What happens in one doesn’t happen in the other. RS: No, I don’t sing

differently. The only thing is that

when I do a recording, I have a much, much larger audience. A

record is a document and it’s forever. People, audiences,

students can go to it to understand or to listen or to compare.

So when I do a recording, I am very careful and do it knowing that I

have an audience of millions and millions of people. I like to

do, if I can, long takes. Each scene once, twice, maybe three

times until I like it. But not piece by piece or note by

note. That’s fake. You lose the spontaneity and stage

presence and the drama. So, when I’m in front of the microphone,

I try to picture the audience, and often it works. I am often

asked which are my favorites…

RS: No, I don’t sing

differently. The only thing is that

when I do a recording, I have a much, much larger audience. A

record is a document and it’s forever. People, audiences,

students can go to it to understand or to listen or to compare.

So when I do a recording, I am very careful and do it knowing that I

have an audience of millions and millions of people. I like to

do, if I can, long takes. Each scene once, twice, maybe three

times until I like it. But not piece by piece or note by

note. That’s fake. You lose the spontaneity and stage

presence and the drama. So, when I’m in front of the microphone,

I try to picture the audience, and often it works. I am often

asked which are my favorites… RS: That is always a very

difficult question. Everyone must

gain their own experience. You can tell youngsters many things,

but until they experience things for themselves, they never

learn. So I encourage them to start as soon as possible because

they have a lot of time ahead to make mistakes. We have a saying

in Italian that translates, “By making mistakes, you learn.”

RS: That is always a very

difficult question. Everyone must

gain their own experience. You can tell youngsters many things,

but until they experience things for themselves, they never

learn. So I encourage them to start as soon as possible because

they have a lot of time ahead to make mistakes. We have a saying

in Italian that translates, “By making mistakes, you learn.”