“Well, in our country,” said Alice, still panting a little, “you'd generally get to somewhere else — if you run very fast for a long time, as we've been doing.”

BD: Is this due in

large extent to the televising of

operas?

BD: Is this due in

large extent to the televising of

operas? BD: Do you think the

supertitles in the theater are

going to ever come to the Met?

BD: Do you think the

supertitles in the theater are

going to ever come to the Met? BD: Tell me about

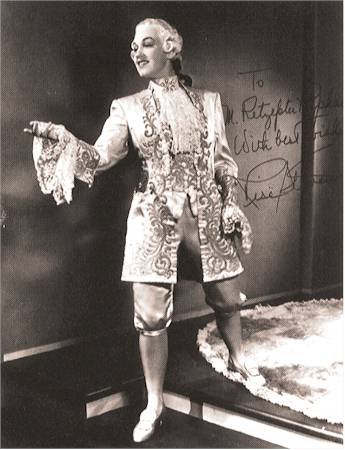

Octavian. How impulsive is he?

BD: Tell me about

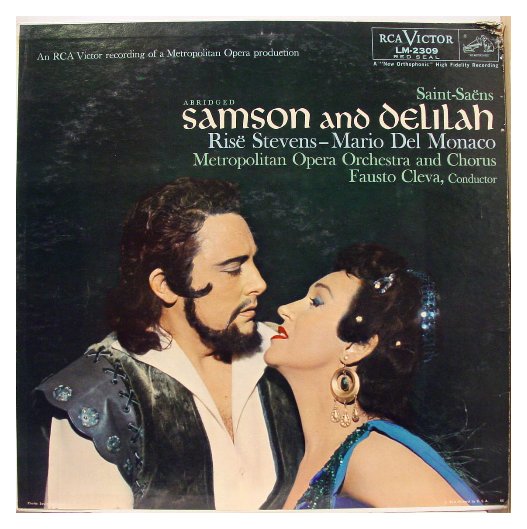

Octavian. How impulsive is he? BD: Did you enjoy

being a seductress

like Dalila?

BD: Did you enjoy

being a seductress

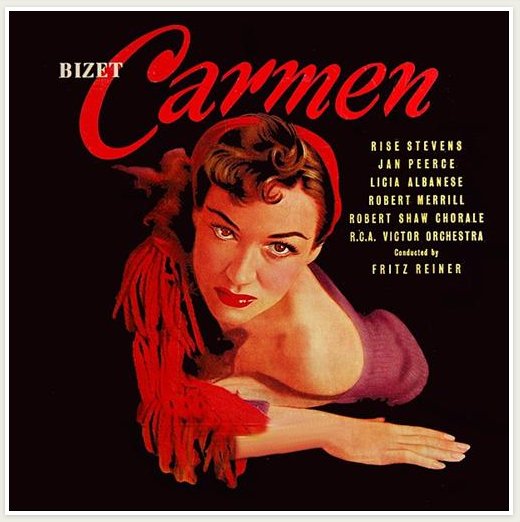

like Dalila? BD: As we talk

about expanding of the role of

Carmen in this production, does your recording with Fritz Reiner

reflect that?

BD: As we talk

about expanding of the role of

Carmen in this production, does your recording with Fritz Reiner

reflect that? RS: I’m

Executive Director of the Metropolitan Opera National Council

Auditions. I’m getting great joy out of this because with this

position I’m trying to discover

those singers that we have in these United States and Canada

who have the potential to start making very fine careers. And

many of them have. In fact, we have something like sixty singers

on the Met roster today that came through our auditions.

RS: I’m

Executive Director of the Metropolitan Opera National Council

Auditions. I’m getting great joy out of this because with this

position I’m trying to discover

those singers that we have in these United States and Canada

who have the potential to start making very fine careers. And

many of them have. In fact, we have something like sixty singers

on the Met roster today that came through our auditions. BD: Do they have too

much power sometimes?

BD: Do they have too

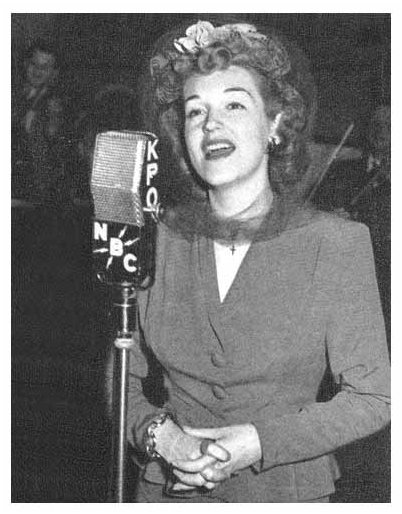

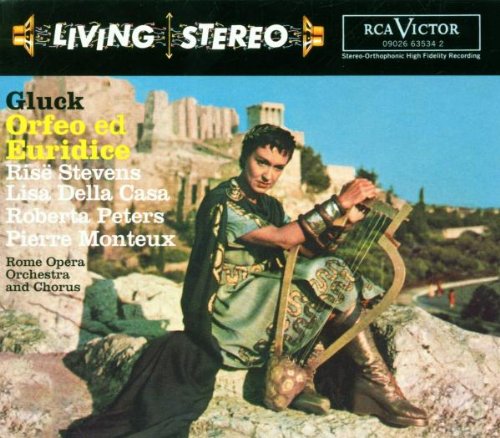

much power sometimes?| The

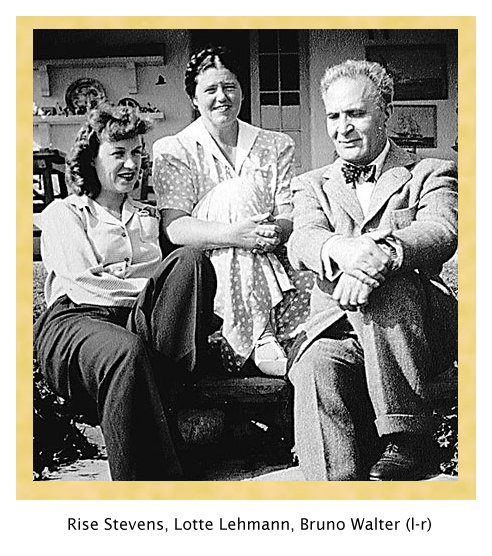

Telegraph 6:29PM GMT 26 Mar 2013 Rise Stevens, who has died aged 99, was a glamorous mezzo-soprano and excelled as an on-stage seductress. Carmen – a role she dominated at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, during the 1940s and 1950s – and Delilah were her stock in trade, and by 1945 her voice was insured at Lloyds of London for a record $1 million. Such was her standing at the Met that when union members threatened to jeopardise the 1961-62 season, she sent a telegram to President Kennedy asking him to intervene – which he did. She was born Risë Gus Steenberg – Risë rhyming with Lisa – in the Bronx, New York, on June 11 1913. Her father, Christian, was a Norwegian Lutheran who sold advertising; her mother, Sarah, was a Polish Jew. She recalled her heavy-drinking father encouraging her to sing along with him to When Irish Eyes are Smiling in their kitchen. Thanks to a musical aunt she earned a dollar a week appearing on The Children’s Hour on local radio. By 1930 she was singing in local concerts in New York using the professional name Stevens and soon joined the Little Theatre Opera Company, supporting herself by modelling fur coats during one of the hottest New York summers on record. She studied at the Juilliard School with Anna Schoen-René, who in 1936 advised her to turn down an offer from the Met in favour of pursuing her studies in Salzburg with Marie Gutheil-Schoder. Her formal debut was in the title role in Mignon in Prague under George Szell; two years later she appeared with the Vienna State Opera, sang Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier in Buenos Aires and made her debut with the Met company in Philadelphia and, a few days later, in New York. The Marriage of Figaro was the opera with which Glyndebourne first opened its doors in 1934. Five years later Risë Stevens joined the stalwarts of that inaugural season – including Audrey Mildmay – to sing Cherubino there . That season she also played Dorabella in Così fan tutte with Roy Henderson, demonstrating her “charming voice and style”. She was booked to return to Glyndebourne for the first production of Carmen there the following year – but by 1940, however, the Sussex opera house was a makeshift nursery school for 240 children from London. During the war she enjoyed a parallel career as a minor film star, appearing in The Chocolate Soldier (1941) with Nelson Eddy, and Going My Way (1944) with Bing Crosby, the latter winning seven Oscars. These appearances only bolstered her operatic career, and by the mid-1940s she was commanding top fees at the Met and had her own weekly radio show. In 1955 Risë Stevens reprised her Cherubino at Glyndebourne, but was unable to carry off the trouser role with the same youthful vitality as two decades earlier, and little was seen of her again in Europe. American audiences seemingly did not mind and the Mozart part remained a mainstay of her repertory for many years along with roles such as Delilah and Octavian. When the Lincoln Centre opened its Music Theatre, she played Anna in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I. After bowing out from the Met in 1961, Rudolf Bing, the Met’s autocratic director, asked Risë Stevens to run the new Metropolitan Opera National Company, which would take the Met’s work to smaller venues around America. Though the project foundered within a couple of seasons, she remained on the Met’s administrative team for many years, offering particular care and attention to young artists. She was also president of Mannes College of Music, New York. During her 124 performances of Carmen at the Met, Risë Stevens felt confident with most of her Don Josés, such as Richard Tucker and Ramón Vinay. However, such was the unbridled enthusiasm with which Mario del Monaco and Kurt Baum played the role that she demanded they be equipped with a rubber knife for Act IV when her character is stabbed. There were other hazards. In 1951, during Der Rosenkavalier, she caught splinters of glass in her eye after dropping a glass on stage. After being treated by a doctor in the wings she was able to continue. Risë Stevens remained a formidable presence to the end, helping two biographers and giving a lengthy television interview at 98. She married Walter Surovy in 1939, and he soon became her manager. She recalled how once “when I dislocated my shoulder singing Carmen he first called The New York Times, then the doctor. As a wife I felt insulted, but as a client I had to bow to him.” He predeceased her in 2001, and she is survived by their son, the actor Nicolas Surovy. Risë Stevens, born June 11 1913, died March 20 2013 |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on April 22,

1985. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB later that year, and again in 1993, 1998, and 2000. It

was transcribed and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.