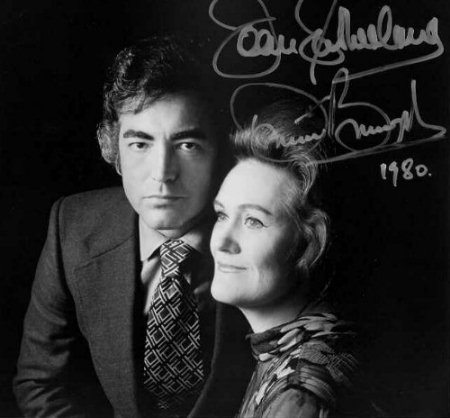

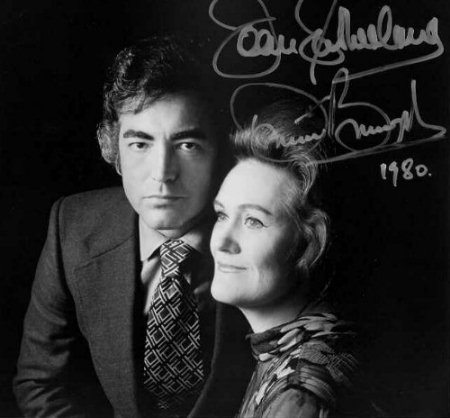

PRESENTING THE COUPLE:

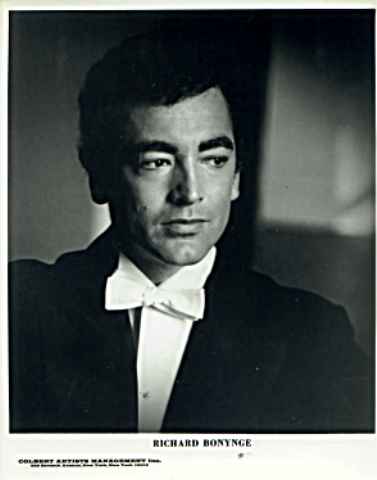

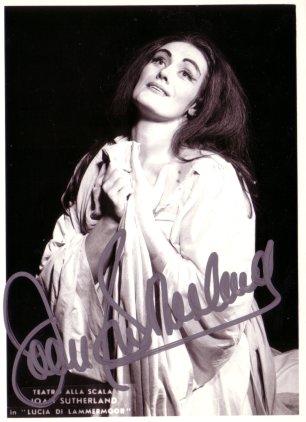

JOAN SUTHERLAND AND RICHARD BONYNGE

By Bruce Duffie

PRESENTING THE COUPLE:

JOAN SUTHERLAND AND RICHARD BONYNGE

By Bruce Duffie

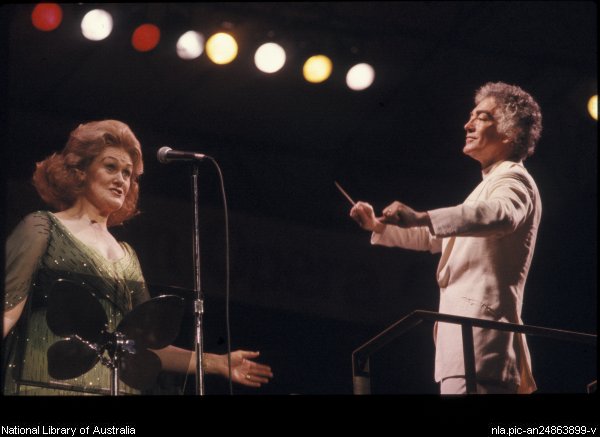

The Massenet Society has, as honorary members of its board, several well-known and distinguished musicians, and at the top of the list are Joan Sutherland and Richard Bonynge. Their contribution to French Music in recent decades is legendary, and we are all honored by their interest in the Society.

In recent days, Dame Joan announced to the world that she will retire from the stage. At an age when most others have long since departed from the public eye, she still has what it takes to give the public what it demands, and she wants to retire before she can no longer please her adoring fans. We will, of course, miss her, but the memories of a glorious career.,.. to say nothing of her recorded legacy - will live on for everyone who keeps Bel Canto close to their heart.

This coming September, the conductor-half of the team turns 60 years old, and to celebrate that milestone, it is my special pleasure to share with you a conversation that the three of us had in Chicago in the fall of 1985, when these artists brought their production of Anna Bolena to the Windy City. The couple was fortunate to be able to live not in a hotel downtown, but rather in a stately mansion in a northern suburb. It was there that they received me, and for about 40 minutes we simply chatted about our favorite subjects.

Looking at the results here on the printed page, I wish that more could be done to share the bouncy enthusiasm of the soprano and the clear understanding of the conductor as they interrupted each other, often finishing their partner's thoughts and then continuing, only to be interrupted back again as the ideas came forth. There was a good deal of laughter and much spontaneous humor mixed in with the serious topics.

So, here is much of that wonderful conversation. Watch the

initials

so you know who is speaking, and if you can get caught up in the whirl

of discussion, you'll feel yourself swept along.

Bruce Duffie: Let me begin by asking about 19th century composers. Did they really understand the voice, or did they wait and find people who could do what they asked and accomplish the tasks that they set down?

Richard Bonynge: I think the 19th century composers were brought up with the traditions of the 18th century where the great school of singing was at its height with the castrati and the very high, stylized form of singing. I think that Rossini, who came out of the 18th century, understood very much how to write for the voice, and you see this right from the earliest of his operas. They're well-written for the voice, and Bellini also came out of that school. As we get later in the century, they seem to have forgotten, or had to re-learn, or change their ideas. Verdi at the very beginning was rather cruel to certain voices.

Joan Sutherland: Not only at the beginning. Some of the Falstaff and Otello are not terribly vocal.

RB: Oh I find Otello quite vocal - at least for the woman.

JS: But she growls a lot in the lower part of the voice.

RB: If you can sing it it's all right.

BD: Well, this is the thing - if you can sing it.

RB: But earlier roles like Odabella in Attila and Lady Macbeth...

JS: Notice I've never sung them!

RB: ...they're not kind to the voice because they expect the voice to do what is not natural. They want you to scream at the top and belt at the bottom and have a lot of punch in the middle. This is very rarely given to one person.

JS: If you do scream at the top and belt at the bottom, you get a hole in the middle very easily!

BD: But what you're saying has been attributed mostly to 20th century composers.

RB: Well, as I said, they started to get bad in the 19th century, and got worse and worse.

JS: But you can't really say that. I have always thought that Cilea is a much neglected and underrated composer, and I'm sure it's because he didn't have Ricordi as an agent. He didn't get on as well as Puccini because he didn't have the Ricordi outlets. He was sort of pushed into the background.

RB: He wrote very beautifully for the voice, and toward the end of the 19th century, you had Massenet and the French school who understood the voice very well. He was hardly capable of writing anything that wasn't good for the voice, and he understood how to set words, which is very important.

JS: He's difficult, but good.

RB: The great voice composers didn't only write easy music. On the contrary they wrote very difficult music because they were writing for established and good singers for the most part. The operas in those days were written with certain singers in mind. Today that very rarely happens.

BD: So we have to find singers - such as Miss Sutherland - who happen to have the right type of voice for what was written.

RB: Or who are able to adapt themselves to that sort of music.

JS: Which is more to the point, I think.

RB: You have to adapt yourself to the music, and in certain Bel Canto music, have to adapt the music to you.

JS: Which is what a lot of singers did, and what a lot of the composers did. You find different versions of the same piece.

RB: Donizetti or Bellini would frequently rewrite a piece for different circumstances.

JS: Or look at L'Africaine [by Meyerbeer] and the little slumber song. There are two versions of that little lullaby.

BD: Well, how much adaptability on the part of the voice can a composer expect of a singer?

RB:

I think a composer can expect a singer to have a good technique. In

those

days, they tended to study. Today, people are born with a voice and

think

they can sing. Unfortunately, the art of singing is one of the most

elusive

of all arts. If it were easy to teach, one would be able to pick up a

book

on singing and learn about it, but you can't. You can read all the

books

you like, but you don't know that much more than when you began.

RB:

I think a composer can expect a singer to have a good technique. In

those

days, they tended to study. Today, people are born with a voice and

think

they can sing. Unfortunately, the art of singing is one of the most

elusive

of all arts. If it were easy to teach, one would be able to pick up a

book

on singing and learn about it, but you can't. You can read all the

books

you like, but you don't know that much more than when you began.

JS: There's different equipment. Everybody has a different physical stature and even a different physical approach. I would say there's only one way to sing and that's the way I find comfortable. But another singer wouldn't sing the same way and yet they may get a fantastic result. Don't know for how long. . . (laughter)

BD: Well, what is the secret to singing for 25, 30, 35 years?

JS: A certain discipline, and the fact that I did have the opportunity to solidify a technique. I also had a very watchful eye that steered me into a course that probably saved my voice. I was singing the Bel Canto roles, and never really did the ones, as we said, that screamed at the top and walloped at the bottom. I think it's been due to that. Because of my stature, I was very set to sing Wagner. I adored Flagstad, but mind you, I adored Ponselle, too. I also adored Galli-Curci. I adored Callas and Tebaldi, but you have to find your own field and stick to it.

BD: You simply adored great singing, then.

JS: Oh I did. The greatest thrill for hearing fantastic sound soaring out of a human throat is wonderful, whether it's male or female.

BD: Is there anywhere today that a person can do their career like you did - stay seven years at Covent Garden doing lots of big and small roles?

JS: I don't know that there really is. The Australian Opera was like that to a certain extent.

RB: There are houses, more in Europe than here, where you can actually sit for months at a time. It's hard in America because the only house that plays all the year round is the Metropolitan, but they are a company which is made up principally of guest artists who come in and out. And a major company like the Met is not where you should learn.

JS: It's the same at Covent Garden. When I went there, it was a basic company and some guest artists. There were four or five sopranos who sang and covered everything. They had guest artists to sing a majority of roles, but that company core learned everything.

BD: Why has this style died out?

JS: The jet has something to do with it, and money. They're better off paying the guest singers and forget about maintaining a company.

BD: Is management not concerned about the individual?

JS: I don't think some managements are vaguely concerned, not vaguely concerned about individuals.

RB: You might say almost all managements are not very concerned with individuals. They are concerned with their own theaters, and some of them are concerned with standards of performance.

JS: But, you see, I went through a period where we had a General Manager who was concerned with individuals, and really tried to foster their careers.

BD: How is a singer able not to become a property?

RB: With the greatest difficulty. It's terribly difficult because when a singer is young, they generally have to earn money, so therefore they must accept work.

JS: They're afraid to say no.

RB: They are often afraid to say no lest they not be offered anything else.

BD: Here in Chicago we have the Opera School [now called the Lyric Opera Center for American Artists]. Is this a good thing, a step in the right direction?

RB: Of course it's a very good thing. The danger starts when they finish with the school. What do they do then?

BD: What, then, should be the next step?

RB: The next step should be that they become a junior member of a company, but that doesn't happen very often. There's nowhere here to do it . . .

JS: Especially with American singers in their own country. It's very, very hard. Some of the American singers have fantastic musical training and fantastic natural voices, but they find it very difficult to be accepted into a company.

BD: Are the singers today as musical as in years gone by, or are they just better trained technically?

JS: Some of them are very musical.

RB: Today there are so many people wanting to break into the singing business that they have to be well-trained musically or they get thrown out. The major companies won't stand for people who are unmusical or ill-prepared. In the old days, it was enough to have a great voice. Coaches were provided and people were taught their roles. It's not quite so easy today. I think a singer has to be much more self-dependent than they had been in the past.

BD: Are there too many young singers coming around?

RB:

I wouldn't say there are too many. There are not enough good

ones.

RB:

I wouldn't say there are too many. There are not enough good

ones.

BD: Are there enough great ones?

RB: Who knows? I don't see them at the moment.

JS: How many great ones were there in any age?

RB: Well, there were a lot more than there are today.

JS: There were, and I think a great deal of the problem lies with the jet.

BD: Have we overblown the idea of greatness in Malibran or Garcia or others?

RB & JS: Oh quite possibly.

RB: We cannot know how they sounded. We might not even like what they did.

JS: The timbre would be very odd, I would think, to us today.

RB: It's hard to say. We can only guess. They may have been wonderful. To take a parallel example, look at the pianists. Technically today, pianists are a great deal better than they were in the 19th century. Evan a great pianist like Cortot, who I have to admit gave me more thrills than many who were much better technically, would play fistfuls of wrong notes concert after concert. Paderewski would play enormous amounts of wrong notes. So did Josef Hofmann. These were very, very great artists, but today, wrong notes are not tolerated.

BD: Is this because of recordings?

RB: I think recordings have a lot to answer for. People sit home with their Hi-Fi equipment and they listen to everything which may not be beautiful, but it's perfect.

BD: So records are too perfect, then?

JS: They can be too perfect, yes.

RB: It depends on who's making the records. It's much more interesting to listen to live performances. Some singers, I think, are fools because they've allowed the record companies to over-boost their voices to such an extent...

JS: ...that they can't sing in the theater, and when they do, they disappoint the public. The public wonders where their voices have gone.

RB: I think that when you record, you should make sure that the recorded sound is as faithful as possible to your own sound...

JS: ...and that is possible!

RB: Mind you, there are certain singers who believe their voices are huge when they're not. That's a difficulty.

* * * * *

BD: When you're singing a role, do you prepare it differently for microphone than for a live audience?

JS: No. In fact, the technicians can do what they like with what you produce. Let's face it, they can turn you up or turn you down. And they very often do turn you down because they want to get the technical balance. Or they sometimes put you in a certain area of the hall because they want a certain balance in an ensemble. I've tried to do things, sometimes, on records, and when I hear the playback it's all ironed out anyway, so I don't really try very much any more. I try to sing accurately and with a reasonable amount of feeling. I certainly try to establish a certain amount of dramatic tension, but the recording technicians make the sound they want to hear on the whole, don't they?

RB:

I don't think they make the sound. They can boost a sound or

they

can take away sound, but when a singer has the microphone in their

throat,

you can always hear that if you listen very carefully.

RB:

I don't think they make the sound. They can boost a sound or

they

can take away sound, but when a singer has the microphone in their

throat,

you can always hear that if you listen very carefully.

JS: London Records has certain distances from the microphone for everybody, and they ask them to keep those distances.

RB: They generally put the mikes over the edge of the stage so you cannot approach them because they're so used to singers leaning forward as far as they can. If you watch certain singers, they almost topple over trying to get to the microphone. But in actual fact, it was explained to us many years ago by the technicians at Decca, that you don't get a better sound by approaching the mike.

JS: You get a drier sound that way.

RB: By getting back, you get a much more glossy sound because you are getting all the resonance from the hall or the room where you're recording.

BD: Do you like the sound you hear coming back on your records?

JS: Oh, I think the sound has improved so much. The sound that they get today with digital recording and playing back on compact discs has no comparison with the old stereo discs. It's wonderful. You hear the same recording from an LP and a CD and there's no comparison. It's the same recording that you made, and it's wonderful to get rid of all that surface noise. There are so many mechanical things that come between actually singing for a record and the record playing back to you in your room. It's like chalk and cheese.

BD: Does Miss Sutherland sound the same in the theater as she does on records?

RB: I would say that in a good theater, she sounds better. She has the sort of voice that the further you go away from it in general, the better it sounds.

JS: (feigning indignation) I'm not sure that that's complimentary! (laughter all around) I know it's meant to be.

RB: For an operatic singer, it's very complimentary because you're generally singing in very large theaters, so that if one gets in the back of the Colon in Buenos Aires, or in the back of La Scala, the voice sounds bigger than if you're very close up. This is a very good thing. You could sit in a room, and some singers deafen you, yet when you go away from them, the sound doesn't really carry so much. If I sit next to Joan singing full pelt in room, it's big. It doesn't deafen, but it will completely wipe out another singer who, on microphone, can sound bigger. It's something I can't explain and I don't know how or why. . .

JS: It's all voice projection.

BD: Can that be trained, or is that just what you're born with?

JS: Projection? Sure, it can be trained.

RB: Talking again about teaching singing, how do you describe that in words? I can't, and I doubt that she can.

JS: It's difficult to grasp even if you're told what to do. You don't get it right away.

RB: I firmly believe that great singing is an instinct that you are either born with or are able to develop. But I don't think it's anything that you can learn intellectually. I think it's something you have to assimilate. It's something you have to feel.

JS: You can learn intellectually to a certain extent. You have to, or you would never form any sort of technique. Never. You have to think where the sound is going and where the sound is coming from.

RB: You're talking about feeling. You're not talking about thinking, you're talking about feeling. You always sang by feel.

JS: But I don't feel anything - that's the awful thing. As soon as you begin to feel anything, you're singing badly. I always say that what you do is breathe, support, and project and that's all you do to sing. But, you have to have the physical vocal equipment. In other words, you have to have the vocal cords that respond to the direction of your breathing, supporting and projecting.

* * * * *

BD: When you're onstage, are you portraying a character, or do you become the character?

JS:

Oh I think it's very dangerous to quite become the character. That's

all

to do with emotions, and letting them sort of carry you away. You still

have to be aware of what's happening. One tries to portray a character.

JS:

Oh I think it's very dangerous to quite become the character. That's

all

to do with emotions, and letting them sort of carry you away. You still

have to be aware of what's happening. One tries to portray a character.

RB: It's very dangerous. If you become a character, you become lost and you wallow in your own emotions...

JS: You aren't in control of what you're doing.

RB: ...You aren't putting them in the back seat of the theater. It's the people in the theater that have to wallow in emotions, not the person doing it. The person has to make the whole theater full of people feel emotions. That doesn't mean you don't feel it. You feel it to project it, but you have to control it. You can't just lean back and enjoy it.

JS: You'll be voiceless at the end of the first act that way.

BD: You do a lot of these loony ladies...

JS: I didn't say that! Another interviewer used those words, but I do often say, "Oh another mad scene."

BD: Well, here's another character going off the deep end. How can you perhaps make her more relevant to women (and men, too) in the mid 1980's?

JS: With historical characters, like Anne Boleyn, Maria Stuarda, Lucrezia Borgia, one can at least read up about them and find out what people through the ages have written about them. Adriana Lecouvreur as well. You can try and get into your own mind an overall conception of what they might have been like, but you almost have to forget about all that and sing the music you're given. Lucrezia Borgia is one of that poisoning family, but the music she has is the most divine, gorgeous music imaginable. There's nothing harsh or cruel about her. She's remorseful, but she doesn't seem evil at all. Everybody else says she's evil, but none of the music that she sings is vaguely evil.

BD: Does this make a conflict within you when you sing it?

JS: It makes it hard to portray that character, so one ends up just trying to be very regal and perhaps dominant. But how can you equate Donizetti's music with the sort of person she is purported to be in the opera? I don't find it possible. But the music survives, and that's the main thing.

BD: If this kind of story were being set today, would the composition teachers and theoreticians say it would be a mistake to write beautiful music for this evil character?

RB: They might well do, but we're back in another age. This was an age of melodrama, and Donizetti, in creating Lucrezia Borgia, was creating a sort of a personage from a drama by Victor Hugo which has precious little to do with history, but it was a good drama. So Donizetti took that drama and wrote a wonderful vocal piece, and it works as such.

JS: So was Rigoletto - a good drama - and also Maria Stuarda.

RB: These pieces worked very well, and the public in those days wanted to hear great music, great tunes, things that were wonderful to sing. They didn't worry if the music for Lucrezia was "evil" or not. How do you write evil music anyway? You can write nasty music or unpleasant music...

BD: This brings me to the question about historical characters. When the librettist plays fast and loose with historical facts, how do you bring that back to reality?

JS: Oh you enjoy them - like the confrontation between Elizabeth and Stuarda. It's wonderful drama.

RB: What the composer has put there is what you do. Donizetti probably knew nothing whatever of the historical characters he wrote about.

JS: There are mistakes about times and places.

BD: So you're not presenting a historical drama, but rather beautiful singing.

JS: You're presenting drama within the bounds of the music...

RB: ...within the bounds of the time that it was written, too. We have to remember what sort of drama the people of those days expected to see in the theater. They expected their emotions to be touched by a sort of melodrama. It's not what people go to see in modern theater today. I don't think you can equate the two. I don't think there's any way you can modernize pieces written in the 18th and 19th centuries. You accept them as they are and perform them as we believe they may have been performed - because we don't know exactly. We must try to recreate them. If you try to modernize them, you'll ruin them. You don't take a painting from the museum and try to make it look like something painted in this century.

BD: But are the audiences that come today expecting something different than earlier spectators?

JS: I don't think the majority does. They think they are coming to a work of a certain period.

RB: If they want something modern, they'll go to Broadway, but even the Broadway pieces that have success are as old-fashioned as they can possibly be. The idiom is almost 19th century with a bit of beat behind it, that's all.

BD:

Is "rock" music?

BD:

Is "rock" music?

JS: Don't ask me that.

RB: I don't think we're in much of a position to say because we don't know much about it. It doesn't appeal to us very much, but it certainly appeals to a great many people, so there must be something about it. It's primitive and very easy to listen to.

JS: Not for me it's not! It's taxing, sort of bang, bang, bang, bang...

BD: Well, should we try to get the people who go to rock concerts into the opera house?

RB: The older I get, I think that people should go and hear what they want to hear and to hell with them. I wouldn't try to educate anybody. Look what happened to the missionaries who tried to educate the so-called heathen in Africa. It didn't do much good.

JS: And India. And Papua. And New Zealand. Everywhere.

RB: Who are we to say everybody must be educated? If somebody wants to be educated, then they educate themselves.

BD: Well, is public taste always right?

RB: No, of course it's not. But on the other hand, it's what keeps one in business. Operas come and go in and out of fashion, and they always will. I would not be at all surprised if in the next century Wagner were not played at all. People might be completely fed up with it. Bel Canto has been right out of fashion for a great many years, and now it's right in fashion, and may again go out again, and in again. Who knows, and what does it matter?

BD: In the 19th century, people seemed to crave only new operas. Now they seem to hate new works and express interest in novelties from back then. Does this make sense?

JS: Well, the writers have disappeared.

RB: People were brought up in the opera house and they learned about singing and they wrote for singers and created beautiful roles for great singers to sing. But then that was done. What do you do today? You can't write more beautifully than has been done in the past, so composers try not to be more beautiful, but to be different.

JS: Now they have become so symphonic.

RB: After Puccini and Strauss, there's hardly a composer one cares about. I speak very personally; I'm aware of that.

BD: If someone today were to write using the 19th century formulas, could that possibly be successful?

RB: I'm sure it could be successful, in fact I'm sure. Kreisler fooled the public by writing pieces "in the style of" older composers. It could work. I'm sure a composer who was clever could write a fake Donizetti and fool the public.

BD: But should he call it a Donizetti discovery, or simply a new work in the old style?

JS: I think he should have the courage to call it his own.

RB: But people are so snobbish that they wouldn't be interested in hearing a work that was merely a copy of somebody else. Certain people might enjoy it, but you're not going to get to a public that way. If you bring out a work and prove that it's by Donizetti, you'll have a great success. If you say it's by Mr. Smith, it will be a flop.

* * * * *

BD: When you're performing, how much do you expect of the public?

RB: I don't think we expect anything. I can tell you that if the public is with you, they always get a better performance from the stage.

JS: We're very conscious of the public's reaction.

BD: How much can the public expect from you?

JS: One does the best one can on any occasion. As Richard says, if you can sense that response or excitement from the public, somehow it thrashes you on to do better things.

RB: It's a matter of pride that whether we're in the mood to perform or not, we have to perform at a certain level. We don't like ourselves if we give bad performances. We're brought up to perform, and to perform well is the only way. I think that somehow the public expects of a singer like Joan almost too much. They expect something quite superhuman, and sometimes she appears that way. It makes it tough. If critics hear Miss X from Timbuktu, they'll say she's absolutely wonderful, but when they hear Miss Sutherland, they criticize at an entirely different level without saying so at all. We go to some opera houses and have four to six weeks of rehearsal, and someplace else will have one rehearsal if you're lucky. The press never criticize in any different way for those things, if they even care to find out.

BD: Is it the press that has made you a superstar?

JS: I don't really think so.

RB: The press help a great deal because they're writing constantly. But this is part of modern life.

JS: The press is paid to go and do a job as I am paid to do a job, whereas the public pays to go and hear me do my job. They still go on paying, and I've seen the same faces in the audience for 30 years in some instances. There's actually a chunk of audience throughout the world that travel. I don't know how they have the money or the time to do it, but some come from Switzerland and Holland to Chicago, and vice versa. It's very, very flattering, and you get very surprised to see them turn up in some completely unexpected place. But they've seen it on the schedule and made it their business to come. They are opera buffs, and if I'm doing something like my only performances of Hamlet on the stage, they turn up in Toronto. They turned up for Esclarmonde, which they probably will not hear otherwise, and for Roi de Lahore in Vancouver.

BD: Is it right to bring back an opera like this just for you?

JS: I think it's right to bring them back just to hear them because it's not just for me. In Esclarmonde, the tenor has some of the most ravishing music that's ever been written for the tenor voice - especially in French opera.

BD: You two have done more toward bringing back these obscure works than probably anyone else - it's like a public service.

JS: Well, some people may be able to live with doing only 5 roles in their whole life, and I've always complained about learning the new ones, but if I had to do only a very few, I'd go round the bend. There's no challenge. Every time you do a role, it's different. And every time you come back to a Lucia or Puritani, you find out something new about it and it's fresh again. But it's only fresh again because you've done a lot in between. You do other styles and types of work. Handel is great for the voice.

RB: It's also very beautiful music.

JS: It's wonderful music, but it's also taxing in a different way from the Donizetti and Bellini works. One sings the same way, but it's like having a vocal lesson. One always sings better after one sings a Handel opera.

BD: Do you ever feel you're a slave to the voice?

JS: Oh frequently. (laughter) I have certain restrictions that I place on myself, and without them I know I can't turn in the performance that, as Richard says, people expect. They really do expect something special, and I feel I have to try and give them something special, so I have to restrict myself in certain areas.

BD: What about some of the roles that you've recorded twice - is one better than the other?

JS: Oh, there's different casts, and the recording technique has improved.

RB: It's always interesting recording works again. One always means to do them better, but whether one succeeds I wouldn't like to say. In general, I find there are things I like in the early one and things I like in the later one. But we don't listen very often to the records. Once we've done a work, we're thinking about the next one.

JS: In the Handel tercentenary year, suddenly I had to re-learn Rodelinda, and I had to do a funny semi-oratorio Athalia, which is a hoot in the most uncommon, funny English imaginable. I was doing my best not to laugh when singing it.

BD: Does opera work in translation?

JS: It depends on what it is, but usually we're better off singing them in the original language.

RB: Certain works do well in English. We've done Fledermaus and Merry Widow in English, and for an English-speaking audience they work better. I like the supertitles in the theater. They're wonderful because you don't have to watch them if you don't want to. But if you don't understand things well, they're of enormous help. I've found them amusing myself, watching in a performance where you don't hear the words too well. Or in a language you may not understand too well, it's interesting to know what's going on. Some people are snobbish and say you should be intent on the emotional content of what's coming across the stage. I don't think that everybody's the same. Certain people who may become a little bored by the opera can be helped a bit by knowing exactly what is happening. Don't tell me everybody in the audience knows what's going on. Half the people singing don't know the scores. (laughter)

JS: Audiences are pretty much the same everywhere, and there is a much bigger response when they understand what you're singing. I think that the supertitles, or surtitles, or whatever they're called, do help in that regard.

RB: The titles are fine, and in some instances translations would be bad because the language is over-flowery and over-romantic, and does not translate well into English. And many phrases are repeated over and over, so one title tells what they're singing and it need not be shown more than once. There is no singer alive or dead who could make the Mad Scene in Lucia sound as good in English as it is in Italian.

BD: You've been most generous with your career and also with your time. Thank you for chatting with me.

RB: Not at all. We've enjoyed it very much.

JS: Yes indeed, it was a pleasure.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Bruce Duffie continues his work at WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago. The station celebrated (in July) its 35th anniversary, and in October, Duffie will finish his 15th year there. In addition to the weekly "Sunday Opera" broadcasts (which often include interview material), he presents many programs of music by living American composers (again, with interviews), as well as a monthly broadcast called "American Romantics" of music by nineteenth-century creators. Recently added to this schedule is a weekly program called "Who's in Town" that features conversation and recordings by artists who grace the Windy City.

In the next issue of this journal, a conversation with soprano

Catherine

Malfitano.

=== === === === ===

--- --- ---

=== === === === ===

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on November 12, 1985 in Chicago, and portions were broadcast on WNIB several times in subsequent years. A portion was also used by Lyric Opera of Chicago as part of a series featuring their Jubilarians on their website in 2004-5, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the company. This transcription was made in 1990 and was published in the Massenet Newsletter in July of that year. It was slightly re-edited from the original and posted on this website in January, 2007.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.