Conversation Piece:

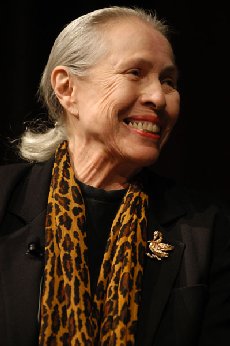

Prima Ballerina MARIA TALLCHIEF

By Bruce Duffie

Conversation Piece:

Prima Ballerina MARIA TALLCHIEF

By Bruce Duffie

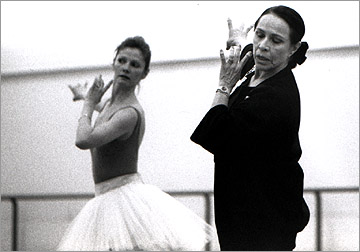

Though it might seem this interview would be better suited to a magazine called "Ballet Journal," my guest, Maria Tallchief, has spent much of her time in the opera house, and, as she notes in the conversation, she loves the music and values voices in a very special and personal way. After enjoying a spectacular career as prima ballerina, she is currently Ballet Director of Lyric Opera of Chicago. [Detailed biographies can be found at the end of this interview.]

Naturally, in a magazine such as The Opera Journal, the emphasis is placed on singers, with stage directors, conductors and a few composers thrown in - since they are also part of the large family that is needed to present this most complicated of art forms. Nowadays, many directors are placing so much emphasis on drama and movement that dance - in various forms - is even more of an integral part of the operatic scene than ever before. So it is fitting that a talent such as Maria Tallchief be brought into the mix, to give her views and insights gathered from a lifetime of being at the top of her profession.

Needless to say, I'd admired the artistry of Maria Tallchief all of

my life, so it was a special pleasure to meet her and be invited to her

home for the conversation in September of 1994. The lovely

penthouse

overlooking Lake Michigan and the "Magnificent Mile" of Chicago was

filled

with creations and mementos from a long and distinguished career.

After walking through several of the rooms, we eventually landed in her

kitchen, where we sat down to record the conversation. As I set

up

the machine, we were chatting about our families - her daughter and

sister,

and my father, who, at the time, was 87 years old and living in

Florida.....

Maria Tallchief: You know, it must be the air. [Laughter] The fountain of youth!

Bruce Duffie: Has the ballet kept you young all these years?

MT: Well, I don’t know! I guess thinking about it keeps me young. [Laughter]

BD: How much of ballet is the movement and how much of the ballet is thinking?

MT: [Thinks for a moment] It’s both. It's a great deal of thought. As I used to tell my students, you live with your ballet and your lessons and what you’ve learned. You don't leave the studio and forget about it. It’s something that you have to think about all the time. Unfortunately, when you’re younger it's tunnel vision. You don’t have time for this distraction or that distraction, really. It takes all your energy. It takes a great deal of thought and dedication.

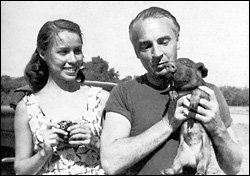

BD: You were with Balanchine as a dancer and also as life partner for a little while. Was it good for the ballet - good for someone in the ballet to be with someone in the ballet, so that the tunnel visions maybe were pointing the same direction?

MT:

They definitely were. This was the beginning of the New York City

Ballet. It was a very important time, certainly in my life, and,

I believe, in Balanchine's life. He had, as you probably know,

been

doing Broadway shows, and his manager wanted him to make a little

money,

[chuckles] so he could live. And he had done movies. He was

associated

with Rodgers and Hart, and I think he liked doing that. But his

true

love, of course, was always music and ballet. When I met him in

the

early '40s, I think he had finally decided that he truly wanted to go

back

into the ballet company and start creating more ballets for that.

This was the time when we started the New York City Ballet. We

began

with Ballet Society of New York City, and that evolved into the New

York

City Ballet.

MT:

They definitely were. This was the beginning of the New York City

Ballet. It was a very important time, certainly in my life, and,

I believe, in Balanchine's life. He had, as you probably know,

been

doing Broadway shows, and his manager wanted him to make a little

money,

[chuckles] so he could live. And he had done movies. He was

associated

with Rodgers and Hart, and I think he liked doing that. But his

true

love, of course, was always music and ballet. When I met him in

the

early '40s, I think he had finally decided that he truly wanted to go

back

into the ballet company and start creating more ballets for that.

This was the time when we started the New York City Ballet. We

began

with Ballet Society of New York City, and that evolved into the New

York

City Ballet.

BD: Is there any kind of music that really cannot be used to make a ballet?

MT: You know, there are various discussions about that. I have to say that there is music that is much easier to dance to than other music. For instance, the last ballet that George created for me was the Gounod Symphony [1958]. Beautiful ballet. The big problem in the second movement, the Adagio, is that it's so quiet. It’s almost like hearing a clock tick. That is very difficult to dance to because he devised very difficult steps. With my partner; we needed to have split-second timing, and suddenly there was just the very silent, very quiet music. Of course you have very quiet music, for instance, in The Nutcracker. The Sugar Plum Fairy is no great bombast, but that’s different. And I found to dance to Stravinsky was wonderful and Tchaikovsky is perhaps the greatest dance music of all... Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, The Nutcracker.

BD: What is it about Tchaikovsky that he knew how to write for people making steps?

MT: It's interesting. I don't know. I’m sure he did not have a balletic background, but he certainly knew what dancers liked, and it's always great satisfaction to dance these wonderful ballets of his, I have to say. And then, also, one thinks of Delibes, the French composer, who wrote such beautiful music like Coppélia, and the others.

BD: Staying with Tchaikovsky just for a moment, did you dance other music of his besides his specific ballets?

MT: Oh, yes! We did the Allegro Brillante, which was done to the Third Piano Concerto [premiered in 1956].

BD: Well, my question is whether his music was more inspired when he was depicting specific ballet-action rather than just planning orchestral music for a concert?

MT: No, I don't think so. The very most wonderful of Balanchine’s great works is the Serenade [which is danced to Tchaikovsky's Serenade for Strings, premiered in 1935]. Once you have seen the ballet that George did to this music, you can’t hear the music without seeing the ballet. There are many works that Balanchine choreographed to music not specifically done for ballet.

BD: Is it particularly satisfying to add something visual to a work which is 'finished' musically?

MT: Well, I have to say that if we’re talking about Balanchine, he was such a musician, first and foremost. This was his first great love. Once he has choreographed and done the steps to this music, it's almost as if you are seeing the music, which, as I said, is wonderful and very satisfying.

BD: We were talking about adding the visual to the music and making it special, and you spoke of Balanchine. In your own work, have you choreographed some full ballets?

MT: [Emphatically and without hesitation] No, no. I am intimidated. Having been around Balanchine for all those years, and having seen his genius, it's very intimidating. I wouldn’t presume to try to choreograph, because it’s just something that I think either you do or you don’t. It’s like having perfect pitch. You either have it or you don’t. I think it’s the same thing. They talk about schools for choreographers. What does that mean? It means, I would think, first and foremost, to know music, to be very well schooled in music.

BD: Is it like a school for a composer?

MT: Well, it’s the same thing, exactly the same thing. [In a tone of voice implying the ludicrousness of such an idea] A school for a composer. Now isn’t that ridiculous? [Chuckles dismissively]

BD: I guess teaching the techniques is possible, but the inspiration has to be their own.

MT:

Yes! Innate talent has to be there, and I don’t feel it is

me.

Balanchine started to choreograph when he was a teenager in Russia, in

St. Petersburg. I was too busy trying to be a good dancer,

frankly,

to even think about anything else. When I became associated with

the opera here, I saw a very special way of choreographing for the

opera.

That glorious singing stops, and suddenly the stage is taken over by

non-singing

dancers. It's a special way of choreographing, of almost

showmanship,

so that once the ear is no longer hearing this glorious sound, and you

have just people dancing to the music, it’s a very special

segment.

I think it takes a great theatricality of choreography, and it's very

special.

MT:

Yes! Innate talent has to be there, and I don’t feel it is

me.

Balanchine started to choreograph when he was a teenager in Russia, in

St. Petersburg. I was too busy trying to be a good dancer,

frankly,

to even think about anything else. When I became associated with

the opera here, I saw a very special way of choreographing for the

opera.

That glorious singing stops, and suddenly the stage is taken over by

non-singing

dancers. It's a special way of choreographing, of almost

showmanship,

so that once the ear is no longer hearing this glorious sound, and you

have just people dancing to the music, it’s a very special

segment.

I think it takes a great theatricality of choreography, and it's very

special.

BD: But you're aware of the fact that there is no singing going along with it.

MT: That’s it. And that’s why you have to take it up with your visual. You have to command that stage visually.

BD: Is it more responsibility?

MT: I think it is. When I danced in the opera here, I felt that it was a great responsibility. I danced in the Ruth Page Orphée years ago, and also in Dance of the Hours in La Gioconda. And it was rather difficult. You know, in the ballet you’re used to getting there two hours ahead of time. You go on the stage and you practice, and you look at the floor, and you practice with your partner. When you dance at the opera, it's almost like you're interpolated. They're very busy doing what they have to do, and then, "Now it's your turn." [Laughter] "Come on in and just dance," you know? So I think it's difficult. But in many ways it's very rewarding. When I still had the company down at Lyric Opera, I remember we did Khovanshchina, with Nicolai Ghiaurov [in 1976]. He was such a consummate actor. Oh, my! Every muscle, every finger, every gesture! And I would say to the dancers, since they didn't have a great ballerina to look at or to emulate, “Watch Nicolai. Look and see how he walks. How he commands the stage, just by standing there." You know, he could do it! And this is the way you learned! When I was a young dancer, in class I always stood right up at the top of the barre, at the beginning of the barre, and the minute I would finish I'd go up there and I'd turn around and look at my colleagues to see what looked right and what didn’t look right. I'd think to myself, "Ah, that's the way I want to do that step." So now it's the same, and I said to them, "Watch Ghiaurov. See every motion, everything." He was such an actor, plus, of course, his glorious voice! It was thrilling! And he placed himself on the stage so beautifully. I've seen other singers who were able to move beautifully, but it doesn’t come naturally to everyone. It’s like anything else. If you ballroom dance, somebody who is wonderful with you is light as a feather, and there are others that you have to drag around the floor. [Laughter]

BD: What advice do you have for singers to be more balletic, or just be better actors on the stage?

MT: Well, you know, that's interesting. Years ago, when I started at Lyric Opera, Carol Fox [the General Director] decided that she wanted to start the young singers in an apprentice school [now called the Lyric Opera Center for American Artists]. She said to me, “Maria, they have to learn how to move, because they are not graceful enough." But I can understand. It'd be the same thing as if somebody said to me, “Maria, you have to sing.” Well, I’m not a singer. I know I’m not a singer! They know they're not dancers, and they’ve been so busy developing these beautiful voices and suddenly they’re told that in the count of eight, you have to go from here to that side of the stage. They're unaccustomed to that. So what I did, I just started doing exercises as I was doing myself in my later years, after I had retired, and we would warm up with stretching exercises. Then we would start playing the music, and sort of learning. What's very difficult, frankly, is to learn how to waltz. It's very difficult. Waltz is very, very difficult, even for ballet dancers. I wasn’t there at the time but when Balanchine was doing the Vienna Waltzes at the New York City Ballet, he discovered that nobody knew how to waltz. [Chuckles] Not one of his great, glorious dancers. The conductor, Robert Irving, was at the rehearsal and suddenly he jumped up and he said, “George!” ...and he started waltzing away. [Laughter] So he taught all these ballet dancers how to waltz! But it’s funny when you say it, because it seems as if it should be so easy.

BD: It’s just three-quarter time...

MT: That’s it, three-quarter time, but you have to be able to do it in a certain space at a certain time. [Laughs] Go round this way and then back around this way... [chuckles]

BD: I remember when I was very young, we did a production in high school of West Side Story. All the chorus people had to audition. Those who could dance were Jets, and those who could not dance were Sharks. So I was a Shark! [Laughter]

MT: I thought you were going to say "Neither." [Laughter all around]

BD: No, no, no... I was a good singer, but I couldn’t move at all. So I certainly understand how difficult it can be.

MT: Well, it's something that I guess they’re being required more and more to do now.

BD: Is it a good thing that the acting in opera now is more realistic?

MT: I would imagine so. Although I can remember when I would hear Renata Tebaldi I didn’t care if she could walk, or stand, or sit, or whatever! [Laughs] Just the sound of that voice was enough for me.

BD:

Just as the stage directors are demanding more realistic action by the

singers in the opera, are they also demanding more realistic action in

the ballet?

BD:

Just as the stage directors are demanding more realistic action by the

singers in the opera, are they also demanding more realistic action in

the ballet?

MT: [Without hesitation]: No, I don’t think so. You see, balletically, you have the choreography, let’s say, from Petipa, from Swan Lake. That's what you do. I learned it from my first choreographer, who learned it from another, you know, who learned it probably from the one for whom it was created.

BD: So there's a direct line.

MT: Yes, a direct line. It's classic dance and these roles are well known. Of course they change a bit. If somebody does this better, jumps better, let’s say, then perhaps in the Variation in Act II, suddenly she may jump more. But in general you follow the same line that was choreographed by Petipa in the original version.

BD: So that would be just a cadenza, then.

MT: Yes. A cadenza, but cadenzas are not something you make up yourself. The cadenza is something that’s also choreographed. It's something that you know is coming. You don’t suddenly decide to do something on your own. [Chuckles] Nowadays in ballet, I don’t really know what the new choreographers are doing. I am told, but I have not seen any of the European choreography. I’m not quite sure it’s something I would particularly like, to tell you the truth.

BD: So then the only way to get new steps or new ideas is to have new music with new ballets.

MT: Well, it doesn’t have to be new music, but it has to be a choreographer. This is what’s important, the person who makes the dances, who creates the dance, who creates the steps.

* * * * *

BD: When a conductor is working with a singer on stage, maybe in the performance they'll watch a little bit, and stretch and give a little bit. Does the choreographer watch the ballet dancers, and stretch and give a little bit, or are you absolutely programmed to every minute detail?

MT:

Well, no. Actually, for instance, Balanchine choreographed for me

32 ballets. I wasn't really aware it was that many, but

apparently

it is. But when he did, he would say, “Now is that

comfortable?”

He never did anything unless it would be comfortable. For

instance,

in the Firebird, he didn't say, "You have to turn to the left

when

I turn to the right." But he would say, “Is that

comfortable?

Is that your best side?" Every dancer has a best side for the

extension

of the leg in second position, or arabesque. One side might be

more

beautiful, or easier, and Balanchine was always very

accommodating.

Later, when somebody else would come in to dance the Firebird,

in

general they would dance the same steps that I had danced.

However,

as time went on, after I had retired in 1966, there were other dancers,

and Balanchine changed the choreography completely, which was fine with

me

MT:

Well, no. Actually, for instance, Balanchine choreographed for me

32 ballets. I wasn't really aware it was that many, but

apparently

it is. But when he did, he would say, “Now is that

comfortable?”

He never did anything unless it would be comfortable. For

instance,

in the Firebird, he didn't say, "You have to turn to the left

when

I turn to the right." But he would say, “Is that

comfortable?

Is that your best side?" Every dancer has a best side for the

extension

of the leg in second position, or arabesque. One side might be

more

beautiful, or easier, and Balanchine was always very

accommodating.

Later, when somebody else would come in to dance the Firebird,

in

general they would dance the same steps that I had danced.

However,

as time went on, after I had retired in 1966, there were other dancers,

and Balanchine changed the choreography completely, which was fine with

me

BD: Was the basic thing still there and he changed it a little bit, or did he scrap the whole thing and start from scratch?

MT: Well, basically the idea, of course, was Stravinsky’s Firebird as he wrote it, and the story was there. But I think within that he would change steps. Years later, when we ourselves did Firebird here with the Chicago City Ballet, I did my original version, and he came out to see it and was very pleased to see that, because he had had to change his own version, perhaps, because, frankly, they couldn't do it.

BD: So every choreographer has to accommodate to a certain degree?

MT: Well, first of all, I think what he does is see if that person is able to do his ideas. Not everybody is a Firebird, just like not everybody is a Swan Queen, and not everybody is a Sugar Plum Fairy... though I happened to be all three! [Laughs riotously]

BD: [Chuckles] Well, you're thinking of your roles, of course.

MT: Well, of course, but, I remember once Jerry Robbins wanted me to dance The Cage, which he had done with great success with Nora Kay. This was one of our great successful ballets of Jerome Robbins and the New York City Ballet. We did it in Europe, every place, and Jerry had said that he would like me to dance it. But I never felt that I would have been able to dance that role the way Nora had danced it.

BD: But couldn’t you dance it the way you danced it?

MT: Well, but it would've been different.

BD: So?

MT: Well, you see, it was a sort of a strange thing. There were some distortions and this and that, and I really didn't feel it was something that I could do justice to, frankly. So I never danced it. I think someone else did it with great success, and that's fine.

* * * * *

BD: Many of these ballets are designed as ballets. The composer thinks of the story as he's going along. What about, as you mentioned, the Gounod Symphony? Obviously Gounod was not thinking ballet when he wrote that work. Is it easier, or harder, or just different to get a design and a scenario for music that doesn’t have one built in?

MT:

This had no scenario. This was just dancing to the music, and I

have

to say that except for the second movement, the first movement was

wonderful,

and the third movement was glorious. It was easy. I was

uplifted

completely by this marvelous music, jumping, you know, and very, sort

of

French style of choreography. It was wonderful. The only

difficulty

was in the second movement, because it was very, very quiet. It

was

not that the choreography was too difficult. I don't know.

Maybe so. However, I have to say, it's interesting that we had

our

greatest success with the Gounod

Symphony in Japan when we danced

in Tokyo in 1958. I think that was one of our greater successes,

which is interesting, isn’t it?

MT:

This had no scenario. This was just dancing to the music, and I

have

to say that except for the second movement, the first movement was

wonderful,

and the third movement was glorious. It was easy. I was

uplifted

completely by this marvelous music, jumping, you know, and very, sort

of

French style of choreography. It was wonderful. The only

difficulty

was in the second movement, because it was very, very quiet. It

was

not that the choreography was too difficult. I don't know.

Maybe so. However, I have to say, it's interesting that we had

our

greatest success with the Gounod

Symphony in Japan when we danced

in Tokyo in 1958. I think that was one of our greater successes,

which is interesting, isn’t it?

BD: Sure, but then the Japanese just love Western music.

MT: Yes. That’s all we did was Western music.

BD: They say music is the universal language. Is dance also as universal?

MT: Yes! Oh, I think so. Absolutely.

BD: It’s the language of sight.

MT: There is no language barrier, and, in fact, when you teach ballet, all of the balletic terms are in French! The first school for ballet was in the French court, so when we teach class, the whole vocabulary is in French: plié, tendu battement, grande battement... And it’s not an affectation; this is our language.

BD: Like all of the musical terms are in Italian: allegro, molto vivace...

MT: Right. But when you dance, you’re not on stage saying "battement tendu," you’re out dancing. I’ve toured all over the world with the New York City Ballet, with American Ballet Theatre, and on my own, actually giving concerts. There has never been any problem.

* * * * *

BD: When you’re dancing, you have the orchestra and the conductor in front of you. Are you conscious of the audience beyond that conductor?

MT: [Without hesitation]: No, not really. You're not really conscious. It’s interesting, though, how one hears the applause much easier in some houses than in others. Our opera house here in Chicago, for instance, is a very long space. In most opera houses, for instance La Scala or the Paris Opera, the boxes were quite close, so that one hears the applause much easier. Here, the applause is great and the bravos are great, but perhaps the performers don’t hear it as well. Sometimes I would come out here straight from the New York City Center where the house was smaller, and they were closer to you, and you have a different feeling of the audience.

BD: Did you change your ballet technique based on the size of the house?

MT:

[Emphatically and without hesitation] No, no. The technique

would be the same, the approach would be the same, the music would be

the

same, everything would be the same. I remember, when we were

going

to go to Covent Garden in London, Frederic Ashton said, “Now Maria, you

know, this is a big house,” and I said, “Well, Freddy, I have danced in

many big houses, so I don’t have to worry about that.”

MT:

[Emphatically and without hesitation] No, no. The technique

would be the same, the approach would be the same, the music would be

the

same, everything would be the same. I remember, when we were

going

to go to Covent Garden in London, Frederic Ashton said, “Now Maria, you

know, this is a big house,” and I said, “Well, Freddy, I have danced in

many big houses, so I don’t have to worry about that.”

BD: Did the size of the stage make any difference to you?

MT: The size of the stage is very important. In general, if you are a big ballet company you cannot dance… or, really, you shouldn’t dance in a small house on a small stage unless you do little concert pas de deux or, something like that. When I was doing lecture-demonstrations it was very interesting: I found that the Hindemith Four Temperaments is music that appeals, strangely enough, to young people. Isn't that interesting? [The Hindemith work is called Theme with four Variations (According to the Four Temperaments) (1940), for string orchestra and piano. The ballet was first performed in 1946 and is entitled The Four Temperaments.] We would do the first three themes. And it’s fun! You know, popular music. I guess you could hum it if you wanted to. [Chuckles] I thought, "Now, I hope this isn’t going to be too serious for them," but they were absolutely fascinated by this music. It is haunting music, if you listen to the very beginning, you know. And we could do this on a small stage. Not the whole ballet, but just those first three themes. You could do them in the basement, or outdoors, or wherever.

BD: You could almost do it in this lovely kitchen.

MT: That’s right. But it’s interesting that when we went to England the first time, we toured after we had finished at Covent Garden, and we went to various other places. I remember one of the theaters was wide but the stage was very narrow, so we had to change the pattern of our choreography. Rather than using this whole rectangular space, it was just very narrow. And it was very difficult. We did Firebird, and I remember thinking, “My heavens, I'm going to fall off the stage any minute!" [Laughter]

BD: Does the height ever change?

MT: The height usually is about the same unless you’re dancing in a small auditorium. For instance, a high school auditorium might not have a great proscenium.

BD: Here in Chicago we have this very tall proscenium.

MT: Very tall, yes, which is good, which is wonderful. This theater [the Civic Opera House, built in 1929, which is where Lyric Opera of Chicago performs] is wonderful, as is the Auditorium [now designated a National Landmark, of which the cornerstone was laid by Grover Cleveland in 1887]. Both are beautiful theaters for dancing.

* * * * *

BD: You dance to music of various periods and styles, though much of it seems to be mostly contemporary music these days. In the concert hall, there is often resistance to new music. Is it part of your design, in dancing to new music, to help bring people to the music, as well as to the ballet?

MT: I don’t know if one would call Stravinsky "new music" these days, but at that time he was. When he created the Orpheus and we danced it, I think Mr. Stravinsky himself conducted our first performance at the City Center [of Music and Drama in New York, April 28, 1948]. Later, he conducted the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall, and Balanchine and I went to hear it. It was interesting that we sat there and all I could see was the ballet. [Laughter] I wasn’t just listening to the music, I was seeing the ballet. I imagine that it’s true that it’s probably designed to help bring people in. For instance, the Lenny Bernstein works, such as those which Jerry Robbins did with great success.

BD: But now there are many small and large ballet companies that are using extremely new music and electronic music too. Is this a good thing?

MT:

I guess so. Any kind of music is good. I like any kind of

music.

I can’t say I’m crazy about rock and roll, but I like it. I like

to dance to it. [Chuckles]

MT:

I guess so. Any kind of music is good. I like any kind of

music.

I can’t say I’m crazy about rock and roll, but I like it. I like

to dance to it. [Chuckles]

BD: It has a good beat!

MT: Yeah. It has a wonderful beat, and that’s all I ask for - a good beat. [Laughs]

BD: Would you dance to a beat without a tune?

MT: Well, you know, you can dance to anything. Look at the Indians. They dance to tom-toms. So there’s your beat!

BD: Being from the Native American culture, did you ever dance something that was about Native Americans, or from their culture specifically?

MT: Not really. When I was a young girl, we had moved from Oklahoma to Los Angeles, California. It was the time of Shirley Temple. Everyone was a new Shirley Temple, and somebody came to my mother and suggested that my sister and I should do an “Indian” dance. In my tribe, the Osages, the men dance, but the women only form a circle and do a sort of little walking step around them. They wear their dresses and their blankets, but it’s the men who do the dancing. So my sister and I did an Indian dance which was quite funny, in retrospect. I hated it, so, just hated it. I was so glad when I grew out of the costume and didn’t have to do it anymore. [Chuckles]

BD: Did you ever ask Balanchine to do something, and give him some ideas and suggestions of how to make it right?

MT: I don’t think he would have presumed to do something like that. He loved the idea that I had an American Indian background. He met my grandmother Tall Chief in Fairfax, Oklahoma, where she lived at that time, and he was fascinated by all that, but I don’t think he would have presumed to do anything such as a legend of the American Indian, because he felt that it wasn’t where he was coming from. People have done it. My sister danced in a ballet that was done in Oklahoma, and they asked me to be part of that. It was Indian legends. But by that time I had retired, so I was not able to participate.

BD: Perhaps we should find a fine composer who is from your tribe, or another tribe, and ask that composer to write music specifically of his or her heritage.

MT: I think that’s been done. I can’t remember the name, but he was an American Indian composer who lived in Santa Fe, New Mexico. I think he is the one that wrote the score for the ballet which was called The Four Moons. [The Four Moons Ballet, pas de quatre (1967), by Cherokee/Quapaw composer Louis W. Ballard, of Santa Fe, New Mexico; movements include: I. Overture, II. Entr'acte, III. Dance of the Four Moons, IV. The Shawnee Variation, V. The Choctaw Variation, VI. The Osage Variation, VII. The Cherokee Variation, VIII. Finale. The ballet received its world premiere to commemorate the anniversary of Oklahoma Statehood, and was performed by four prima ballerinas, all born in Oklahoma and of American Indian heritage.] I was not there. As I said, I had retired and was home taking care of my child and my husband.

BD: Is there something balletic about taking care of a family?

MT: There’s something very satisfying about taking care of a family, having taken care of one myself all of those years. I had this glorious child, and I loved living in Chicago, which was my husband’s home, the city of his birth. People said, “Oh, Maria, you retired much too early.” I was just 41, and I said, “Well, you know, my daughter had turned seven, and school was serious, so I couldn’t say, 'Come on, we’re going off to Hamburg' and take her with me.” So it was a time for me to retire, and I enjoyed watching her grow, and watching my husband as he grew in his work, in his construction business. I have no regrets, and now I love my association with Lyric Opera, though there are not always many ballets during a season. Frankly, I love being around the opera house. To me there’s nothing more glorious than the human voice. I would give anything to be able to sing. People laugh when I say that, but I would! I remember Mr. Stravinsky once called Balanchine, and I answered the phone, and he said, “Oh, Maria, are you a singer?” I said, “No, Mr. Stravinsky, unfortunately I'm not. I wish I was.” And he said, “You have a voice like a singer.” [Laughter]

BD: Is there ever a case where the singer should be a good enough ballet dancer to do his or her own ballet?

MT: Well, I remember in Khovanshchina, which we did here at Lyric in 1976, Ghiaurov actually partnered Helene Alexopoulos, who was the lead dancer. My brother-in-law, George Skibine, who was Russian, of course, did the choreography, and he became a very good friend of Ghiaurov. They thought it was very amusing that Helene would be coming leaping into the arms of Ghiaurov. He did it beautifully.

* * * * *

BD: It’s sort of common knowledge these days that musical performers have gotten technically better over the years. Have dancers also gotten better lately?

MT:

Well, there’s great controversy about that. I don’t know. I

wish I could say that they have. Maybe they have. I don’t

think

so. I’ve been on certain panels where somebody has suddenly said,

[in a pretentious and overly commendatory tone] “Oh, the dancers

of today…” Well, when I go to see the performers of the ballets

that

I danced, I find that rather than doing the difficult steps, some of

them

are being left out! That stopping on a dime, which was required

when

I was a performing, was a nightmare. I would do two pirouettes

and

stop and suddenly jiggle, and that could be the worst thing in the

world

you could possibly do. Now I find that people today don’t always

demand of themselves this split-second timing right on the music.

Perhaps this was something that was demanded. I demanded it of

myself.

That’s the way it was choreographed, and that's the way I did it.

There was no discussion about it.

MT:

Well, there’s great controversy about that. I don’t know. I

wish I could say that they have. Maybe they have. I don’t

think

so. I’ve been on certain panels where somebody has suddenly said,

[in a pretentious and overly commendatory tone] “Oh, the dancers

of today…” Well, when I go to see the performers of the ballets

that

I danced, I find that rather than doing the difficult steps, some of

them

are being left out! That stopping on a dime, which was required

when

I was a performing, was a nightmare. I would do two pirouettes

and

stop and suddenly jiggle, and that could be the worst thing in the

world

you could possibly do. Now I find that people today don’t always

demand of themselves this split-second timing right on the music.

Perhaps this was something that was demanded. I demanded it of

myself.

That’s the way it was choreographed, and that's the way I did it.

There was no discussion about it.

BD: Maybe it’s inflation. Instead of having to stop on a dime, which is very small, now you have to stop on a silver dollar, which lets you have a lot more leeway.

MT: A great big silver dollar. [Laughter]

BD: Well, we’re kind of "dancing" around this, so let me ask the big question. What is the purpose of ballet?

MT: To entertain. As Balanchine said, you take a beautiful person and they become more beautiful on the stage. And that’s true. That’s what it is. Very often, some friend of mine will have seen a ballet, and when I see them later, I will ask, "Were the girls beautiful, and were the men handsome?" If I don’t receive an immediate response, then I know that the dancers had not succeeded. That’s what it is - they become more beautiful.

BD: Well, if ballet is supposed to be entertainment, where's the balance between that entertainment and the art?

MT: The art is there from the very beginning. This is what it’s all about. From your first plié you are learning to become an artist. In every sense the word you are poetry in motion. And if you are fortunate enough, as I was, to be connected with the genius of Balanchine, then you are not only poetry in motion, but you are actually the music. In my mind, that is what it’s all about. The other day I had a horrible discussion with somebody who said to me, [in a glib, offhand tone of voice] “Oh, well, music’s not important."

BD: [Laughs, obviously finding great humor in such a point of view]

MT: I had to leave the table. I just left the table, because I thought, and I said, "I can’t believe that you’re serious." He said, “Well, in New York, when people go to the ballet, they don’t care if the music’s good or not.” I said, "But they can’t dance well if the music is not good. They have to be inspired, they have to be lifted by the music. When you are able to relax within this music, you are showing your artistry." And that’s what it’s about.

BD: Maybe this poor unfortunate person at the table should see a ballet danced to the New York phone book. [Chuckles]

MT: Well, it’s interesting. I’m wondering if he just thought maybe he had not taken part much in the conversation, because we were talking about the New York City Ballet, as opposed to Ballet Theatre. I guess he thought maybe he would just fling something out. [Laughs] And he certainly got a response.

BD: Is there any competition amongst the various ballet companies?

MT:

Oh, I think so, I think so. It’s sad to say. I think

nowadays

the only company that seems to have no monetary problems is the New

York

City Ballet. And I’m sorry to know that, because American Ballet

Theatre is a great company. Joffrey is a wonderful, smaller

company.

Certainly Robert Joffrey, in his own way, was amazing, the way he

created

that company, but I think everyone has problems with funding.

Living

here in Chicago, you don’t always know what’s going on in New York, but

it seems that the New York City Ballet does very well. I’m glad

to

hear that, because when I was there, we lived from year to year, and

only

The Nutcracker saved us, and there was great controversy about

that.

I remember the critic from the The New York Times said, "Oh,

they're

spending money to do The Nutcracker? How

ridiculous."

Balanchine did it; I think it cost something like $500,000 at that time

[1954], but if we had not done it, I don’t think we would've lasted

more

than one more year. The Nutcracker absolutely was our

staple

every year. We even took it out to California in the summertime,

and danced it at the Greek Theatre with great success! Why

not?

Christmas in summer. [Laughs]

MT:

Oh, I think so, I think so. It’s sad to say. I think

nowadays

the only company that seems to have no monetary problems is the New

York

City Ballet. And I’m sorry to know that, because American Ballet

Theatre is a great company. Joffrey is a wonderful, smaller

company.

Certainly Robert Joffrey, in his own way, was amazing, the way he

created

that company, but I think everyone has problems with funding.

Living

here in Chicago, you don’t always know what’s going on in New York, but

it seems that the New York City Ballet does very well. I’m glad

to

hear that, because when I was there, we lived from year to year, and

only

The Nutcracker saved us, and there was great controversy about

that.

I remember the critic from the The New York Times said, "Oh,

they're

spending money to do The Nutcracker? How

ridiculous."

Balanchine did it; I think it cost something like $500,000 at that time

[1954], but if we had not done it, I don’t think we would've lasted

more

than one more year. The Nutcracker absolutely was our

staple

every year. We even took it out to California in the summertime,

and danced it at the Greek Theatre with great success! Why

not?

Christmas in summer. [Laughs]

BD: [Chuckles] Sure! It’s a cool breeze!

MT: A cool breeze.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of ballet in America?

MT: I hope so. I’m a little worried, but, as I said, I’m not in New York City. I know that it’s very popular there, that the houses are full, and they have new people there, and there’s lots of great, enthusiastic audiences. I don’t know if you’re aware of this, but when I was there as the prima ballerina, I was the Woman of the Year. I was at the White House dancing. I was constantly in the magazines among the Top Ten Women. I was more often than not on every list! Of course, this is what Balanchine did for me. I became a star! An international star. Now I don’t see that happening. I see lists, but I don’t see any ballet dancers on those lists.

BD: One last question: is dancing fun?

MT: You know, it’s interesting to me that you should

ask

that. Recently I saw Darci Kistler, who is the first ballerina

now

of the New York City Ballet, and she is dancing a role which was

created

for me, and which I danced. We re-opened the Vienna Opera House

[in

1955] with the Sylvia Pas de Deux by Delibes. It was

beautiful,

wonderful, you know, bravura, very difficult. So I said to Darci,

“Oh, I hear you are dancing Sylvia,.” and she said, “Oh, yes,

and

it’s so much fun!” Well I thought, [chuckles, somewhat

incredulous

and taken aback] “Fun? Gosh, isn’t that wonderful that

somebody

can think that way." I mean, you have almost impossible things to

do there. And I said to her, “Well, I think to dance to that

music

is fun.” Yes, it’s a beautiful score with beautiful, lilting

music,

and then you have the Pizzicato Polka in the middle, and that

is

fun music. Yes, that’s true. In that sense it’s fun.

=== === === === ===

----- ----- -----

=== === === === ===

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This interview was held September 19, 1994, in Chicago. Portions were aired on WNIB in 1995 and 2000, and a brief segment was used by Lyric Opera of Chicago on its website devoted to their Jubilarians (significantly important members of the company) in celebration of its 50th Anniversary Season in 2004.

This transcript was made in November, 2006, and was posted on this website at that time. It is scheduled to be published in a future issue of The Opera Journal.

* * *

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interivews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.

* * *

| From the National Women's Hall of Fame website...

Acknowledged as the most technically accomplished ballerina ever produced in America, Maria Tallchief began her studies with such notable dance teachers as Bronislava Nijinska and joined the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Over the next five years, she attracted much attention with memorable performances, particularly of the works of choreographer George Balanchine. After marrying Balanchine in 1946, the couple left the Ballet Russe and formed what eventually became the New York City Ballet. In her 18 years with this company, Tallchief was the foremost exponent of Balanchine's choreography, as well as the company's prima ballerina for a number of years. Among her most significant roles were Symphomie concatenate, Orpheus, The Firebird, Scotch Symphony, Caracole, Swan Lake and The Nutcracker. Tallchief, through her artistic style and excellence, continued to inspire national and international recognition for American ballet until her retirement in 1965. Through the years, she also promoted Native American culture and contributions to the arts. In the 1970's, as a Chicago resident, Tallchief served as artistic director of the Lyric Opera Ballet, and in 1980 founded the Chicago City Ballet, where she also served as artistic director. When the State of Oklahoma honored Tallchief in 1953, she was given the honor name of Wa-Xthe-Thomba, meaning "Woman of Two Worlds." This name celebrates her international achievements as a prima ballerina and Native American. * * * Additional Resources:Maynard, Olga. Bird of Fire: The Story of Maria Tallchief. New York: Dodd, Mead 1961. NOTES: Covers Tallchief's youth and career. Livingston, Lili Cockerville. American Indian Ballerinas Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997. With Larry Kaplan. Maria Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina. New York: Henry Holt, 1997. With Rosemary Wells. Tallchief: America's Prima Ballerina New York: Viking, 1999. NOTES: Juvenile literature.

|

| From the Kennedy Center (where she was honored in 1996):

Maria Tallchief

"A ballerina takes steps given to her and makes them her own. Each individual brings something different to the same role," Maria Tallchief once said. "As an American, I believe in great individualism. That's the way I was brought up." Tallchief has been both muse and instrument, both the inspiration and the living expression of the best our country has given the world. Her individualism and her genius came together to create one of the most vital and beautiful chapters in the history of American dance. She was born in an Indian reservation, her father member of the Osage tribe, her mother of Irish and Scottish descent. When the family relocated to Los Angeles, young Maria began music lessons and soon found that she had perfect pitch. But it was the dance that would capture the young girl's heart. Her teacher was Bronislava Nijinska. After five full years of study with that dance pioneer, Maria Tallchief joined the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, where she soon achieved soloist status and danced in a variety of ballets from Scheherezade and Gaite Parisienne to, prophetically, George Balanchine's Serenade. Balanchine himself saw Tallchief for the first time in the operetta Song of Norway, where she danced in the corps and understudied Alexandra Danilova. Balanchine fell in love with the dancer, who became his wife in 1946 and the inspiration for, among others, Balanchine's Symphonie Concertante, Sylvia: pas de deux, Orpheus, Night Shadow, The Four Temperaments, and Scotch Symphony. Husband and wife first collaborated at the Paris Opera, in a sort of extended working honeymoon in 1947. Balanchine then brought Tallchief home to his Ballet Society, the company that would become New York City Ballet. Her immense popularity with the American public would grow in part from the huge demand the then small company put on this gifted principal: Tallchief was called upon to dance as many as eight performances a week, and her legend grew. Her dedication was complete, her abandon astounding. Lincoln Kirstein noted his impressions of the by then Mrs. Balanchine in Firebird in his diary in 1949, New York City Ballet's first season. "Maria Tallchief made an electrifying appearance, emerging as the nearest approximation to a prima ballerina that we had yet enjoyed." He was not alone in his praise. Perhaps the critic Walter Terry described it best when he encountered Tallchief in the 1954 world premiere of Balanchine's now historic version of The Nutcracker at City Center. "Maria Tallchief, as the Sugar Plum Fairy, is herself a creature of magic, dancing the seemingly impossible with effortless beauty of movement, electrifying us with her brilliance, enchanting us with her radiance of being. Does she have any equals anywhere, inside or outside of fairyland? While watching her in The Nutcracker, one is tempted to doubt it." In the 1955 Pas de Six, Balanchine made use of Tallchief's innate subtlety and delicacy to such effect that it would take other great ballerinas in the same role for the world to realize just how very difficult technically this ballet is: She made it look easy, natural, musical and radiant. She was, in short, the living essence of a Balanchine ballet. Yet when Balanchine's attentions shifted to another dancer--and another wife--Tallchief found other outlets for her own genius. She joined the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo as a guest artist in 1955 and 1956, famously receiving the highest salary ever paid any dancer. She remarried in 1956, took her only leave from ballet in order to become a mother in 1958, returned briefly to the New York City Ballet to create Balanchine's Gounod Symphony, then joined the American Ballet Theatre in 1960. Even as Firebird became her signature role around the world, Tallchief's personal triumphs ranged beyond Balanchine and even into Antony Tudor's Jardin aux lilas and Birgit Cullberg's Miss Julie, in which she was partnered by Erik Bruhn at the American Ballet Theatre. She was Rudolf Nureyev's partner of choice in the young Russian defector's American debut in 1962, on television. Tallchief surprised the world by announcing her retirement in

1965.

She had no intention of dancing past her considerable prime. She now

wanted

to pass her love and respect for her art to younger dancers. She became

the artistic director and beloved teacher of the Chicago Lyric Opera

Ballet

in 1975; from 1981 to 1987, Tallchief became the founder and artistic

director

of the Chicago City Ballet. "New ideas are essential," Tallchief said

at

the time, "but we must retain respect for the art of ballet--and that

means

the artist too--or else it is no longer an art form."

|

|

From the Houston Institute for Culture... Firebird from Oklahoma Born a mixed-blood named Betty Marie Tall Chief, daughter of an Osage father and Scotch-Irish mother, Maria Tallchief spent eight years in the Indian lands of northeastern Oklahoma. She was born in the small town of Fairfax, Oklahoma in 1925. Like so many Oklahomans, her family moved to Los Angeles in 1933. She enjoyed music and dancing, and practiced being a star -- a considerably challenging dream for a Native American child in those days. Reporting her story would be interesting, regardless of her accomplishments. She would surely have fascinating experiences as she looked back at her mixed Indian and European heritage, her eight years in the Osage Hills north of Tulsa, her journey to California and life among the many people in Los Angeles. After all, those were the days when people became rich with oil fields and poor with dusty crops. Of her childhood she wrote, "I was a good student and fit in at Sacred Heart (Catholic School). But in many ways, I was a typical Indian girl -- shy, docile, introverted. I loved being outdoors and spent most of my time wandering around my big front yard, where there was an old swing and a garden. I'd also ramble around the grounds of our summer cottage hunting for arrowheads in the grass. Finding one made me shiver with excitement. Mostly, I longed to be in the pasture, running around where the horses were..." But, there's more. She became a "Woman of Two Worlds." The Osage Nation became rich from the oil found beneath their land. Young Betty Marie vacationed with her family in Colorado Springs, where she attended a ballet lesson at the Broadmore Hotel. She followed her dream to be a ballerina. Studying with Bronislava Nijinska for five years led to a nervous appearance at the Hollywood Bowl. Madame Nijinska's philosophy of discipline made sense to Tallchief. "When you sleep, sleep like ballerina. Even on street waiting for bus, stand like ballerina." Betty Marie continued to work hard and mastered technical skills well beyond her years. A refined professional, Maria Tallchief, as she called herself, left Los Angeles at the age of 17 and auditioned in New York City. She joined the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and quickly rose to the status of featured soloist. Choreographer, George Balanchine wrote several of his most famous works for her and the two briefly married. She performed for the New York City Ballet from 1947 to 1960, where Balanchine was the principal choreographer. Her performance of Balanchine's Firebird in 1949 and their earlier collaboration at the Paris Opera elevated Maria Tallchief onto the world stage. She received high praise from critics for her performances in France and Russia. Much of the world had never seen anything like Maria Tallchief. Admired by millions, she became America's preeminent dancer, a Prima Ballerina, and in 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower declared her "Woman of the Year." When the Governor of Oklahoma honored her that same year for her international achievements and her proud Native American identity, Maria Tallchief was named Wa-Xthe-Thomba, "Woman of Two Worlds." She continued to dance with the American Ballet Theatre through 1965, when her retirement saddened the artistic world. Throughout her career, Maria Tallchief managed an intense rehearsal and performance schedule, and taught at the School for American Ballet in New York City. Following her retirement, she continued to give her creative talents to the art by directing at the Lyric Opera Ballet of Chicago. With her sister Marjorie, she founded the Chicago City Ballet in 1981 and served as its artistic director through 1987. Maria Tallchief was honored as one of America's most revered artists by the Kennedy Center in 1996, along with prize-winning playwright Edward Albee and music legend Benny Carter. But all of her fame and glory never changed her understanding of her culture. She always admired the Osage ceremonial dances and the ways of her ancestors. She reported being upset by teasing that she and other Native American children suffered. She researched the history and origin of her tribe, learning how they came to reside in Oklahoma. Of the terror her tribe and her own relatives experienced she wrote, "Cousin Pearl was an orphan, and our family was concerned for her well-being. When she was small, her house had been firebombed and everyone inside killed, murdered for their headrights (oil royalties paid to each member of the Osage Nation). Pearl's situation was not uncommon. In the 1920s, villainous White men married into Osage families, then poisoned their wives or shot them in order to get their money, another example of the slaughter of Indians that is a notorious chapter of U.S. history." Tallchief's ideals and many accomplishments have strong influence on young scholars today. A 10-year-old student from Burbank, California, who enjoys sharing the same first name with the famous dancer, wrote to Maria Tallchief, "You made a great impact on the world and on me with your great talent." In a school report published on the Internet, a fourth grade

student

named Veronica wrote, "She is still alive right this minute and

inspiring

young people to do ballet."

-- Mark D. Lacy

|