BD: When you are offered

a commission how do you decide to accept

or reject it?

BD: When you are offered

a commission how do you decide to accept

or reject it? BD: Oh I see, they go

along but they are not seeing what they are

playing.

BD: Oh I see, they go

along but they are not seeing what they are

playing. BD: Music is always a

struggle?

BD: Music is always a

struggle? IX: To be

independent. I have taught in Bloomington, at Indiana

University. I taught music

composition for the students, and I do not know what the result is

because I left and came back to Paris.

IX: To be

independent. I have taught in Bloomington, at Indiana

University. I taught music

composition for the students, and I do not know what the result is

because I left and came back to Paris. BD: Why does there always

seem to be a connection between

mathematics and music?

BD: Why does there always

seem to be a connection between

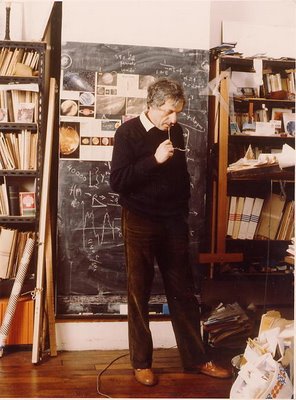

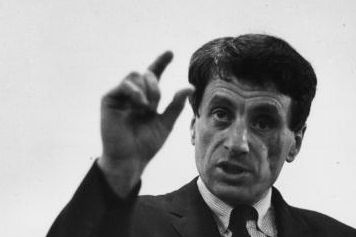

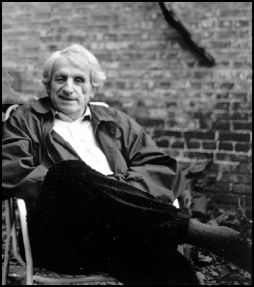

mathematics and music? Composer, architect, civil engineer; Iannis Xenakis was

born 29 May

1922, in Braïla (Romania). Son of Clearchos Xenakis and Fotini

Pavlou;

married Françoise Gargouil 1953; one daughter, Mâkhi.

Fought in Greek

Resistance, World War II, was condemned to death; became a political

refugee in France from 1947, and a French national in 1965.

Education: Athens Polytechnic Institute, music composition studies at

Gravesano with Hermann Scherchen, and at the Paris Conservatoire under

Olivier Messiaen. Collaborated as engineer and architect with Le

Corbusier 1947-60. Innovator of mass concept of music, stochastic and

symbolic music through introduction of probability calculus and set

theory into instrumental, electro-acoustic and computerized musical

composition; inventor of several compositional techniques constituting

the "lingua franca" of the avant-garde. Architect of the Philips

Pavilion, Brussels World Fair 1958 and of other architectural projects

such as the Couvent de la Tourette (1955). Composer, architect, civil engineer; Iannis Xenakis was

born 29 May

1922, in Braïla (Romania). Son of Clearchos Xenakis and Fotini

Pavlou;

married Françoise Gargouil 1953; one daughter, Mâkhi.

Fought in Greek

Resistance, World War II, was condemned to death; became a political

refugee in France from 1947, and a French national in 1965.

Education: Athens Polytechnic Institute, music composition studies at

Gravesano with Hermann Scherchen, and at the Paris Conservatoire under

Olivier Messiaen. Collaborated as engineer and architect with Le

Corbusier 1947-60. Innovator of mass concept of music, stochastic and

symbolic music through introduction of probability calculus and set

theory into instrumental, electro-acoustic and computerized musical

composition; inventor of several compositional techniques constituting

the "lingua franca" of the avant-garde. Architect of the Philips

Pavilion, Brussels World Fair 1958 and of other architectural projects

such as the Couvent de la Tourette (1955). Sonic, sculptural and light compositions: Polytope for the French Pavilion, Expo 1967, Montreal; music and light spectacle Persepolis set among the ruins and the mountains at Persepolis, Iran (1971); Polytope de Cluny, Paris (1972); Polytope de Mycènes, set in the ruins of Mycenae, Greece (1978); Diatope for the Inauguration of the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (1978). Founder (1965) and Director (1965-) of the Center for Studies of Mathematical and Automated Music (CEMAMu), Paris; Associate Music Professor, Indiana University, Bloomington (1967-1972) and founder of the Center for Mathematical and Automated Music (CMAM), Indiana University, Bloomington (1967-1972); research at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Paris (1970); Gresham Professor of Music, City University London (1975); Professor at the University of Paris I-Sorbonne (1972-1989). Xenakis died 4 February 2001 in Paris. |

Iannis Xenakis is one of the leaders of modernism in music, a hugely influential composer, particularly in the later 1950s and 1960s, when he was experimenting with compositional techniques that soon entered the basic vocabulary of the twentieth-century avant garde.  Xenakis was born, not in Greece, but in Braïla,

Romania, of

Greek parents, on 29 May 1922. His initial training, in Athens, was as

a civil engineer. In 1947, after three years spent fighting in the

Greek resistance against the Nazi occupation, during which time he was

very badly injured (losing the sight of an eye), he escaped a death

sentence and fled to France, where he settled and subsequently

became

an important element of cultural life. Xenakis was born, not in Greece, but in Braïla,

Romania, of

Greek parents, on 29 May 1922. His initial training, in Athens, was as

a civil engineer. In 1947, after three years spent fighting in the

Greek resistance against the Nazi occupation, during which time he was

very badly injured (losing the sight of an eye), he escaped a death

sentence and fled to France, where he settled and subsequently

became

an important element of cultural life. Xenakis was first active as an architect, collaborating with Le Corbusier on a number of projects, not least the Philips Pavilion, designed by Xenakis, at the 1958 Brussels World Fair. It was in the 1950s, too, that Xenakis’ compositions began to be published. In 1952 he attended composition classes with Olivier Messaien, who suggested that Xenakis apply his scientific training to music. The resulting style, based on procedures derived from mathematics, architectural principles and game theory, catapulted Xenakis to the front ranks of the avant garde – although there was never any suggestion that he was a member of a clique or group: he was always his own man. He never, for example, embraced total serialism, and he also avoided more traditional devices of harmony and counterpoint; instead, he developed other ways of organising the dense masses of sound that are characteristic of his first compositions. These stochastic, or random, procedures were based on mathematical principles and were later entrusted to computers for their realisation. But for all the formal control in their composition, Xenakis’ scores retain an elemental energy, a life-force that gives the music an impact of visceral effectiveness: works like Bohor for electronics (1962), Eonta for piano and brass quintet (1963-64), Persephassa for six percussionists, placed around the audience (1969), and the ballet Kraanerg, for 23 instrumentalists and tape (1969) all exhibit a primitive power that belies the complexity of their origins. The Sydney Morning Herald said of Kraanerg, for example, that it "remains staggeringly powerful and clamorous, an essay in constantly renewed energy that shows not the least sign of faltering". Married with this primordial power is the composer's fascination with ritualism, most often that of ancient Greece, finding fullest theatrical form in his setting of the Oresteia (1966). Iannis Xenakis is published by Boosey & Hawkes. This biography can be reproduced free of charge in concert programmes with the following credit: Reprinted by kind permission of Boosey & Hawkes. |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on March 25,

1997.

Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNIB two months later. An exact transcription was

made and published in the Sping 2008 issue of SONUS. It has been slightly

edited for presentation here on this website late in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have

been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

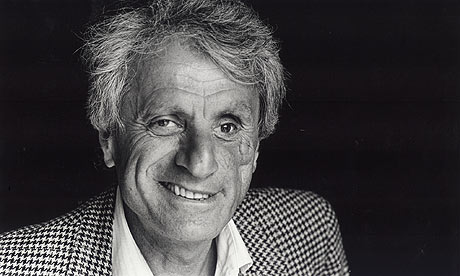

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.