TM: It's different for

different pieces. Sometimes I have been thinking about a piece

for a

long time, and for one reason or another I haven't

been able to get to it. Perhaps I have been finishing off

something else, so

it has to go into cold storage. I hope that it doesn't lose some

of

its savor for me when I take it out and begin work on it. Take,

for instance, Narcissus

[(1987), for flute and digital delay system].

I had the idea for that

really quite a long time before I was able to start work on it, and I

couldn't wait to start. That piece did make use of something not

very new,

technologically, because in the old days it used to be tape loop

or tape feedback. Now, of course, it's done by digital delay

system, so new technology creeps in there, but it's not, actually, a

very new idea. To write a 15-minute piece for solo flute is

quite a tall order to make it really carry, and I didn't want to

do a flute-and-piano piece; I wanted to do something different.

The idea came to me that if I used this digital delay or echo

feedback —

which you hear on practically

every television ad —

and it was about Narcissus, it would

work because the live flute is Narcissus but the feedback represents

his reflection. So it works dramatically as an idea, as well as

making use of a new technology.

TM: It's different for

different pieces. Sometimes I have been thinking about a piece

for a

long time, and for one reason or another I haven't

been able to get to it. Perhaps I have been finishing off

something else, so

it has to go into cold storage. I hope that it doesn't lose some

of

its savor for me when I take it out and begin work on it. Take,

for instance, Narcissus

[(1987), for flute and digital delay system].

I had the idea for that

really quite a long time before I was able to start work on it, and I

couldn't wait to start. That piece did make use of something not

very new,

technologically, because in the old days it used to be tape loop

or tape feedback. Now, of course, it's done by digital delay

system, so new technology creeps in there, but it's not, actually, a

very new idea. To write a 15-minute piece for solo flute is

quite a tall order to make it really carry, and I didn't want to

do a flute-and-piano piece; I wanted to do something different.

The idea came to me that if I used this digital delay or echo

feedback —

which you hear on practically

every television ad —

and it was about Narcissus, it would

work because the live flute is Narcissus but the feedback represents

his reflection. So it works dramatically as an idea, as well as

making use of a new technology. TM: Ohhhhh. Well, I

guess somewhere in the middle. Some of my pieces are lighter and

some of my pieces have

more serious application. For instance, in the opera I

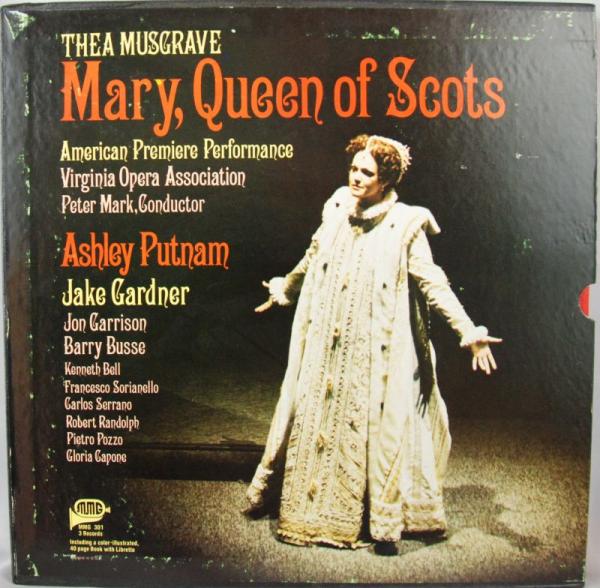

certainly hope to grab people. In fact, in Norfolk, when Mary, Queen of

Scots was done, somebody said they really

liked the story. They weren't quite sure they understood the

music, but they really liked the story. Now I was very

pleased by that because I made story, after all, and what they didn't

realize was that the music actually told

the story. The story is there, of course, but the music really

held the story together. They hadn't realized that, but they were

held by what

was happening on stage. So I was pleased because it meant that

they had taken the first step; something had grabbed them, and I hoped

they would go

back. Maybe they would then hear more of the

music. So it was a first step for somebody who was

not very familiar with contemporary music, who didn't know the style

particularly well, and nevertheless was held by something.

So that I was pleased with.

TM: Ohhhhh. Well, I

guess somewhere in the middle. Some of my pieces are lighter and

some of my pieces have

more serious application. For instance, in the opera I

certainly hope to grab people. In fact, in Norfolk, when Mary, Queen of

Scots was done, somebody said they really

liked the story. They weren't quite sure they understood the

music, but they really liked the story. Now I was very

pleased by that because I made story, after all, and what they didn't

realize was that the music actually told

the story. The story is there, of course, but the music really

held the story together. They hadn't realized that, but they were

held by what

was happening on stage. So I was pleased because it meant that

they had taken the first step; something had grabbed them, and I hoped

they would go

back. Maybe they would then hear more of the

music. So it was a first step for somebody who was

not very familiar with contemporary music, who didn't know the style

particularly well, and nevertheless was held by something.

So that I was pleased with. TM: You try

to make it a good piece; it doesn't always

happen. It's something you don't have total control

over. Like with all artists, you really

try to make it absolutely the best that you can at that

particular moment, but for one reason or another it

may not quite work out the way you had hoped. In my own case, and

I guess with a lot of people, it goes in kind of waves. You get

on a roll and you write a certain number of pieces in that kind in

style, and then there comes a patch where it's more difficult, where

you're changing. New things are coming into the

style, and you have to find new things. You're finding your

path, and maybe one or two pieces at that stage are much

more difficult to write because you're finding new ground. You

work through that and get on another roll. That I don't

have control over because I don't want to go on writing the old

piece. You have to forge on; you have to allow yourself

to explore new things, I believe. It has to be fresh and new and

interesting, always.

TM: You try

to make it a good piece; it doesn't always

happen. It's something you don't have total control

over. Like with all artists, you really

try to make it absolutely the best that you can at that

particular moment, but for one reason or another it

may not quite work out the way you had hoped. In my own case, and

I guess with a lot of people, it goes in kind of waves. You get

on a roll and you write a certain number of pieces in that kind in

style, and then there comes a patch where it's more difficult, where

you're changing. New things are coming into the

style, and you have to find new things. You're finding your

path, and maybe one or two pieces at that stage are much

more difficult to write because you're finding new ground. You

work through that and get on another roll. That I don't

have control over because I don't want to go on writing the old

piece. You have to forge on; you have to allow yourself

to explore new things, I believe. It has to be fresh and new and

interesting, always. BD: What about the

recordings?

BD: What about the

recordings?  BD: Is the music of Thea

Musgrave great?

BD: Is the music of Thea

Musgrave great? TM: Yeah!

Yeah. But on the other hand, another recent opera

was Harriet, The Woman Called Moses,

which is very different from my

experience. What grabbed me about that was

the universality of that experience. It can speak to

everybody. [Harriet, The Woman

Called Moses (1984), opera

in two acts; libretto by the composer based freely on the life of

Harriet Tubman; commissioned jointly by the Virginia Opera and the

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden] I think that that's

something else that an art can do —

transcend time and

space. With time, hopefully through seeing Mary, Queen of

Scots, one can understand something about her even though she

lived so

many hundreds of years ago. Harriet

for me is a big space difference. Coming from Scotland

and talking about slavery in Maryland is a long way

from my own personal experience, yet there's something that's universal

about the kind of courage that she had that can speak to

everybody. That can hopefully be a universal experience.

People can speak to one another through an art and reach

another kind of understanding which goes beyond just words.

TM: Yeah!

Yeah. But on the other hand, another recent opera

was Harriet, The Woman Called Moses,

which is very different from my

experience. What grabbed me about that was

the universality of that experience. It can speak to

everybody. [Harriet, The Woman

Called Moses (1984), opera

in two acts; libretto by the composer based freely on the life of

Harriet Tubman; commissioned jointly by the Virginia Opera and the

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden] I think that that's

something else that an art can do —

transcend time and

space. With time, hopefully through seeing Mary, Queen of

Scots, one can understand something about her even though she

lived so

many hundreds of years ago. Harriet

for me is a big space difference. Coming from Scotland

and talking about slavery in Maryland is a long way

from my own personal experience, yet there's something that's universal

about the kind of courage that she had that can speak to

everybody. That can hopefully be a universal experience.

People can speak to one another through an art and reach

another kind of understanding which goes beyond just words. BD: Do you

enjoy the travel all over the world, taking your music to new places?

BD: Do you

enjoy the travel all over the world, taking your music to new places?|

|

This interview was recorded in the composer's apartment in New

York City on March 21, 1988.

Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNIB two months later, and again in 1993 and 1998.

This

transcription was

made and posted on this

website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.