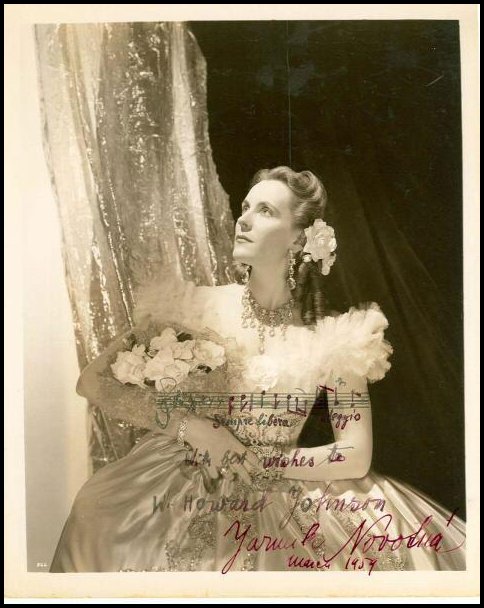

Presenting Jarmila Novotná

By Bruce Duffie

Presenting Jarmila Novotná

By Bruce Duffie

Nobility of bearing; pride in homeland; understanding of artistic richness; confidence; joy and happiness with herself and her surroundings. These and many other positive traits belong to soprano Jarmila Novotná.

Born in Prague in 1907, she studied there with the legendary Emmy Destinn, who herself had sung all over the world in the great opera houses, and was paired on occasion with Caruso - most notably in the world premiere of Puccini's Fanciulla del West in New York in 1910. Novotná also studied in Milan, and made her debut in Prague as Marenka in Smetana's Bartered Bride. From there, her career blossomed and engagements all over the world followed. She also created the title role in Giuditta by Franz Lehár opposite Richard Tauber.

Novotná came to America as Butterfly in San Francisco in 1939, and sang in several important cities. From 1940 until 1956, she was a distinguished member of the Metropolitan, where her repertory included Mozart, Verdi, Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier, as well as Manon and Melisande. She passed away on February 9, 1994.

On one of my infrequent visits to New York City (in March of

1988),

I arranged to meet and talk with this gracious woman. Charming and

delightful,

we spent an hour chatting about her career and her various ideas about

performances then and now. Here is much of what was said that

afternoon...

Bruce Duffie: You have sung a number of roles by Mozart, so tell me the secret of singing his music.

Jarmila Novotná: The secret lies in Mozart's music itself and its extraordinary musical diversity. The singer must be able to express what Mozart clearly puts in the music. Take for instance the two arias of the Queen of the Night. These are not only technical showpieces; heartbreak and entreaty fill the first, while vengeance and fury fill the second. The artist must have these emotions at her command, otherwise she is misplaced in the role.

BD: What are the Mozart roles you sang most often?

JN:

Probably Cherubino because I love it. However, in Vienna and Salzburg,

I sang the Countess. I see her as a person with charm and wisdom and

place.

In the 18th century, women aged very quickly, but to me, she is gay and

capricious, and not a martyr to a dull marriage. Once in awhile, she

has

fleeting thoughts on aging, and it brings a tear to her voice.

Basically,

though, she's a very happy person. We also see her receiving the

adoration

of the young Cherubino with no displeasure at all. I find it

delightfully

human. (laughing) And in the end, she forgives her philandering husband

when he pleads, "Contessa, perdono." This leads to a real apotheosis of

all that is good in human art and all that is so beautiful in Mozart's

music.

JN:

Probably Cherubino because I love it. However, in Vienna and Salzburg,

I sang the Countess. I see her as a person with charm and wisdom and

place.

In the 18th century, women aged very quickly, but to me, she is gay and

capricious, and not a martyr to a dull marriage. Once in awhile, she

has

fleeting thoughts on aging, and it brings a tear to her voice.

Basically,

though, she's a very happy person. We also see her receiving the

adoration

of the young Cherubino with no displeasure at all. I find it

delightfully

human. (laughing) And in the end, she forgives her philandering husband

when he pleads, "Contessa, perdono." This leads to a real apotheosis of

all that is good in human art and all that is so beautiful in Mozart's

music.

BD: Did you prefer singing one role over the other?

JN: I adored them both, but Cherubino's liveliness and constantly changing mood appeals to everybody. He sings of love and is in love with every woman he sets his eyes on, but I think he likes to talk about it more than he experiences it. In his aria he says, "When I sing of love and no one listens to me, I speak of it to myself."

BD: You mentioned earlier that the characters have changed somewhat from the 18th century to the present day. How has the public's attitude toward Mozart changed in the last 50 years?

JN: I think the appreciation of Mozart is greater than ever before. In fact, Mozart was not a great favorite with the Metropolitan audiences. I remember when I sang Cherubino here in 1940, the opera (Figaro) was being given a new production after an absence of 22 years. But because all of us who participated had sung the work under Bruno Walter in Salzburg, it simply sparkled. The audience was entranced, and it remained in the repertory after that.

BD: Did you sing any music composed before Mozart?

JN: I did a bit, but mostly in concert. There were a few arias and songs by Handel and Pergolesi and Scarlatti, and I also sang Gluck's Orfeo, and that was beautiful both here and in Salzburg with Bruno Walter. That had a great appeal for the public. Did you know that Gluck was pure-blood Czech? His name in Czech means little boy. He was born in Bavaria just across the boarder from Bohemia, son of Bohemian parents, who returned to die in their native land.

BD: You've sung so many roles over you career, do you distinguish between the lyric ones and the dramatic parts?

JN: The roles I sang were not really dramatic. Maybe the aria from Tosca or something like that, but never the whole opera.

BD: How, then, did you decide which roles you would accept to sing, and which you would let go?

JN: The only time I refused to sing a role was in the Vienna State Opera, when Clemens Kraus wanted me to sing Carmen. It would have suited me histrionically, but I don't think so vocally. It should be a real beautiful mezzo, so I said no. Then once, (in 1947), I received a letter from Richard Strauss asking me if I'd like to sing Arabella. I answered that I loved that opera, but I didn't think my voice was dramatic enough, and that the orchestration would cover it. He replied, "Don't worry. I can arrange it so that your voice will soar above the orchestra." But I never sang the role. What pains me is that those letters, and all our possessions were seized in 1948 in our home in Czechoslovakia. They are all gone.

BD: When thinking about roles which are offered, is it difficult to say no?

JN: (laughing) One must really be aware of what one can do and what one shouldn't do.

BD: Have you advice for young singers on that subject?

JN: I think it is only sensible to say no if you feel the role is not right for you or for your voice. I would advise every young singer to study rigorously for several years and not give in to the temptation of using the voice in public before it is technically secure. However, I should not speak like that because I started when I was only 17 years old! My first opera at the Prague National Opera was Bartered Bride and a few days later Traviata and three months later I sang Queen of the Night. Those are roles which demand enormous knowledge. Before that, I had studied with Emmy Destinn, who came back to her native land in 1923. She kindly gave me lessons when she was there, and then advised me to study with a baritone with the National Opera. But I knew that was not sufficient, so I went to Italy to study. I've studied all my life and never stopped, but it might have been much better to have waited a few years. (laughing) I don't know. . .

* * * * *

BD: Returning to some of your roles, perhaps your most famous part is Violetta in La Traviata. Was this a favorite of yours, too?

JN:

(Laughing) Yes, because I was 17 when I first sang it, and it is a part

which offers an extraordinary opportunity of displaying all the facets

of the talent both vocally and histrionically. Physically, the role is

equally demanding, and lack of one of these attributes can bring

failure.

The premiere of the work itself in Venice was a disaster because the

soprano

weighed 200 pounds. I was lucky with my first Traviata at the

Metropolitan

Opera in 1940. The critics said I was "a singing Duese." I was lucky to

work with Max Reinhardt in Berlin, and he helped me utilize my natural

acting talent to the utmost. I learned so much from him, and later I

was

able to live the parts even though they were so very different one from

another. One should not see me, but rather the character I had to

portray.

JN:

(Laughing) Yes, because I was 17 when I first sang it, and it is a part

which offers an extraordinary opportunity of displaying all the facets

of the talent both vocally and histrionically. Physically, the role is

equally demanding, and lack of one of these attributes can bring

failure.

The premiere of the work itself in Venice was a disaster because the

soprano

weighed 200 pounds. I was lucky with my first Traviata at the

Metropolitan

Opera in 1940. The critics said I was "a singing Duese." I was lucky to

work with Max Reinhardt in Berlin, and he helped me utilize my natural

acting talent to the utmost. I learned so much from him, and later I

was

able to live the parts even though they were so very different one from

another. One should not see me, but rather the character I had to

portray.

BD: When you are on the stage, do you portray the character, or to you become that character?

JN: I feel one should become the character. Naturally, one portrays it because it is you who does it, but if you study beforehand everything about the role, you really can have the mannerisms that the character has to use. Reinhardt taught me to be the character. That's the important thing. Today, young people sing beautifully and technically well, but I've seen performances when I didn't cry at the end. It surprised me that I was not moved.

BD: OK, if you became the character onstage, how long did it take you to shake it off after the performance?

JN: Oh, that was no problem. I don't see how anyone can remain the character once you're back in the dressing room. (laughing) It's just for the moment when you portray it. It's not something that would last for the whole day.

BD: Coming back to Violetta for a moment, what, if anything, should be done to make her speak more directly to the audiences of the late 1980's?

JN: Are women really different today? She was, what was called then, a woman of light virtue, but she was in the highest echelons of the aristocracy. It's really a story of how she changed after becoming entranced by the love of Alfredo. Have women really changed so much? When one is in love, one is warm and radiant.

BD: But now we have so many more years of collective experience, and the times have changed and life is moving so much more quickly. Do these characters still speak to us today even though we have endured so much?

JN: In the theater, you just look at it as portraying some beautiful woman. Sometimes one would like to be like her. (laughing) She had plenty of fun in life.

BD: There are still Traviatas today?

JN: Oh yes, definitely. Maybe there are even more today, but this is something we don't know. It depends on the woman. It's an interesting question, and I never thought about it.

BD: Thinking about Verdi, did he write well for the voice?

JN: Oh, beautifully. It was really Bel Canto at its best; real balsam for the voice.

BD: Is this a failing of the young composers - that they don't understand the human voice?

JN: I don't know. The modern composers compose what they hear from the outside of their life, and it's so hectic and so quick. The intervals needed to sing in modern music are certainly very bad for the voice. I remember singing something new when I was young in Berlin, and I almost lost my voice. I was not prepared for it, and it was not good. The composers must know the voices of people, but their inspiration obviously makes them write things like that.

BD: Should we develop some singers who can sing these odd intervals?

JN: Well, they do. As I mentioned, some young singers are so technically advanced that it probably gives them the opportunity of not hurting themselves.

* * * * *

BD: Tell me about another of your characters - Manon.

JN: As you know, there are two operas about her - the Puccini and the Massenet. They are similar. Both are pleasure-loving creatures abandoning love for luxury and that brings them to their doom. In the Massenet work, I loved her aria, "Adieu, notre petite table." It endows the character with a moving real-life quality. The music is very transparent and elegant. Puccini's setting is really Italian. The music is more passionate. I loved them both.

BD: Is this something that makes the character great - that it can sustain the French lyricism and the Italian virility?

JN: That certainly can speak for it. Each one has a different approach. It's lovely and I like her in the Massenet more than the Puccini.

BD: Of course there is more to her in the Massenet - more character and more scenes, so you can fill her out more.

JN: Yes, yes, that's right.

BD: Talking about opera in general, where is the balance between the art and the entertainment?

JN: It is art, definitely, because you have to work hard to be able to become an artist. But at the same time, it is an entertainment. People go for many reasons and today there is so much going on during each performance. And not only do we have the performances and the radio broadcasts, but the televised performances have a great appeal. The translation on the TV screen is also very helpful. Many people like opera in the original language, and some works just don't lend themselves to translation. Pelleas et Melisande is an example. They tried it in Boston and it was a disaster. They never did it again in translation. The music is so inside of the whole thing, so the original French is much better for it. On the other hand, in some comic operas like Magic Flute or Bartered Bride or Così fan Tutte, translation helps the audience enjoy it even more. When I was starting out, all the countries of Europe sang opera in their own languages and not the original. Germany, Austria, France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, all of them. So, I was brought up on it, and found it quite natural.

BD: Is that a better idea?

JN: Not completely. Sometimes one can't understand what the people sing anyway, so it's difficult to say whether it's better. (laughter)

BD: Did you work harder at your diction when you knew it could be understood by most or all of the audience?

JN: Oh yes. I tried to pronounce in a way as to be understood. There are singers you can understand all of what they sing, and others you get absolutely nothing.

BD: Have you seen this new gimmick of using supertitles in the theater?

JN: Not yet. I should go to the New York City Opera where they have it. I'm told the people appreciate it, and I don't think it disturbs you to look quickly at the text and then back to the stage. It's good. The texts are on the TV screen, and I think that helps.

BD: Do you think opera itself works well on television?

JN: Yes, it does. It broadens the audiences and expands the number of people who then go to the theater.

BD: Let's speak about The Tales of Hoffmann. Are his three loves really different women, or are they guises of the same person?

JN: I think that Hoffmann just loves women, and his imagination makes him think that all women are similar. But in the opera, I don't think they are one and the same person.

BD: Is it better, then, to just sing one of the ladies, rather than all three in same performance?

JN: It's better to sing just one, but I did do all three at the Vienna State Opera. I liked to concentrate, though, on just one, and Antonia was a great success under Reinhardt in Berlin in the big house. The critics mentioned that what remained in their minds was the last act and Antonia. I also enjoyed doing Giulietta, but it's a completely different character, naturally. For the doll, there is just the aria with its technical virtuosity, and you have to do the movements in such a way that the audiences knows it's mechanical and not a living person. For a singer to do all three is just to show that you can do them all, but it's better to play just one.

BD: Another role - Tatyana in Eugene Onegin.

JN: (smiling) Ohhh, I adore her. It's so romantic. The letter scene reminds me of the first time I was in love. It's a pity that Onegin had a roving eye and did not recognize her sincerity immediately. I think they could have been happy together. At the end, he comes back to her, but it is too late and she is faithful to her husband. She's a lovely, beautiful character. I was so pleased because my son has a child and they named her Tatyana.

* * * * *

BD: Let us move to some Czech operas. You've already mentioned The Bartered Bride several times. . .

JN:

Well, that's a real folk-opera. In this opera, Smetana's approach to

national

music is best revealed. He never used popular folk-songs. All his music

is original. You know the story - she is a young peasant girl who wants

to marry another peasant, but her parents want her to marry a rich

farmer's

son. The marriage broker paints a glowing picture of this rich young

man's

qualities, but when he appears, the crafty girl loses no time in

convincing

him that the girl he is supposed to marry would make his life

miserable.

Well, the marriage broker doesn't want to lose his commission, so he

offers

a deal, on the condition that the eventual suitor for the girl be a son

of the rich farmer. But the girl thinks she has been betrayed, and

there

is a beautiful aria which I loved to sing. In the end, it comes out

that

the peasant boy is the long lost son of the rich farmer, so everyone is

happy except the broker. It's just a lovely folk-opera, very simple and

very nice.

JN:

Well, that's a real folk-opera. In this opera, Smetana's approach to

national

music is best revealed. He never used popular folk-songs. All his music

is original. You know the story - she is a young peasant girl who wants

to marry another peasant, but her parents want her to marry a rich

farmer's

son. The marriage broker paints a glowing picture of this rich young

man's

qualities, but when he appears, the crafty girl loses no time in

convincing

him that the girl he is supposed to marry would make his life

miserable.

Well, the marriage broker doesn't want to lose his commission, so he

offers

a deal, on the condition that the eventual suitor for the girl be a son

of the rich farmer. But the girl thinks she has been betrayed, and

there

is a beautiful aria which I loved to sing. In the end, it comes out

that

the peasant boy is the long lost son of the rich farmer, so everyone is

happy except the broker. It's just a lovely folk-opera, very simple and

very nice.

BD: Is this one of the things that brings the audiences again and again because they know it will work out and everyone winds up happy in the end?

JN: Yes that, and because you want to dance throughout the whole opera. I sang that opera in many American cities - New York, Boston, Cleveland, Chicago, Dallas, San Antonio, St. Louis, Seattle, Cincinnati, and others.

BD: Tell me about singing in Chicago.

JN: Oh, well, I really loved Chicago. My first appearance was in 1940 at a Symphony Hour concert conducted by Maurice Abravanel. I sang Louise's aria, Vilia lied, and a French song, and the review stated that, "Novotna triumphantly fulfills Chicago's expectations."

BD: Well, we expect only the best!

JN: Later I sang Traviata with Tito Schipa whom I adored. He entranced me so much that once when we had a duet, I looked at him and looked at him, and forgot to sing! I'm ashamed to tell you about it, but I got many beautiful write-ups. I enjoyed coming back there.

BD: Did you always read the reviews?

JN: Oh sure. Even when it was bad, you got advice on how to do something better. I remember one time singing Marriage of Figaro in Holland. We went to get the papers to see the reviews, and the headlines read, "Hitler invades Poland." We were already scheduled to come to America for performances, but we managed to arrange for the rest of the family to leave with us. We were very glad to be able to come just before the war. That was something.

* * * * *

BD: Not only were you an opera singer, but you also made movies. Tell me about doing films.

JN: Some are shown still. I started my first one in 1925 in Prague. It was called, "Sun Worshippers" and I don't remember anything about it. Then in Berlin we did one right after the fire that destroyed part of the Vienna opera house. I then did Milloker's Bettelstudent and also Bartered Bride, "Night of the Great Love" for which Robert Stolz wrote the music. Then "Song of the Lark," Lehár's Frasquita, and the best film was "The Search." That is really a moving picture. We made it in 1947 in Germany, and it was a grim reminder of the war. It's about a mother and her little son who are torn apart in a concentration camp and they lose each other. He flees and is picked up by an American soldier played by Montgomery Clift. This was his 2nd film, but the first had not yet been shown, so it was his introduction, and he was wonderful. He was a fine colleague and we had a wonderful time. Anyway, the soldier wins the boy's confidence and teaches him to speak, while the mother goes from one camp to another looking for her child, and finally they find each other. I was also in "The Great Caruso" with Mario Lanza. That was a wonderful voice.

BD: Could he have made a career with the voice alone?

JN: Not completely. Perhaps in the theater, but he was originally a rather heavy man. He had to lose all the time for the films. He'd eat a lot before he recorded the music, then have to lose for the photography. That was probably not good for his health, but he had the potential of being a great singer. He had a beautiful, lovely sound and a good technique. I think he did sing in one opera house one time.

BD; Are you pleased with the recordings you made?

JN; I didn't make too many records. One I really like is the lullaby from The Kiss of Smetana, and the Czech folk songs I did with Jan Masaryk. He was the foreign minister and the son of our President, but the family was enormously musical. The mother was originally from French Huguenots, and emigrated to Czechoslovakia. Her family were music teachers, and Jan was a wonderful pianist.

* * * * *

BD: Let me ask about Puccini. Was he the heir to Verdi?

JN: I don't think he had to be an heir. They were two giants, and we recognized them as such when we sang. They were both wonderful. His melodies and arias are immortal.

BD:

Where is opera going today?

BD:

Where is opera going today?

JN: I think it still has great potential. I firmly believe it has a great future in the United States. Television will help to popularize it. People who see it on the screen will want to see it in the theater. The message is getting around that opera is not "highbrow" but rather good and exciting theater based on real and significant human values. There are more small companies than ever before. It used to be just the Metropolitan, San Francisco, and Chicago. My colleague Peter Dvorsky says Chicago is the opera house he likes best in the world.

BD: When singing all over the world, did you change your technique for the big houses or small houses?

JN: That's difficult to do. That's the trouble with the big houses - some people want to produce more volume and they start to yell. That's bad for the voice, and probably the reason some young singers disappear. There are some wonderful singers coming now.

BD: Without naming names, do you feel the great singers of today are on the same level as the great singers of yesterday and the day before?

JN: I don't think it's right to compare. Each time is different. They have their time and their wonderful voices; we had our time and our wonderful voices. It is more difficult now because of the haste. They have to be here one day and there the next and yet another place the day after. We had an ensemble for the season, and you could improve upon a role during the season. The time during the war (1940-45) was the most wonderful- period of the Metropolitan because no one could go back to Europe and no one could come from Europe. So we were an ensemble, and even now those of us who are still around are very good friends. Even though we sang the same roles, we were not jealous of each other.

BD: Did you enjoy singing concerts as much as you did opera?

JN: Oh yes. Each of the songs had to be an entity.

BD: Like little, tiny operas?

JN: Yes. I liked it. I gave 60 concerts in a year.

=== === === ===

===

--- --- --- --- ---

=== === === === ===

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded March 26, 1988 at Jarmila

Novotná's

home in New York City, and was first published in The Massenet

Newsletter

in June, 1992 to celebrate her 85th birthday. It was posted on

this Website in September, 2006, and the photos (from the collection of

Sandy Steiglitz) were added at that time. Audio portions were

also aired (along with recordings) on

WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, in 1992 and 1998.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.