BD: It's a very long

career!

BD: It's a very long

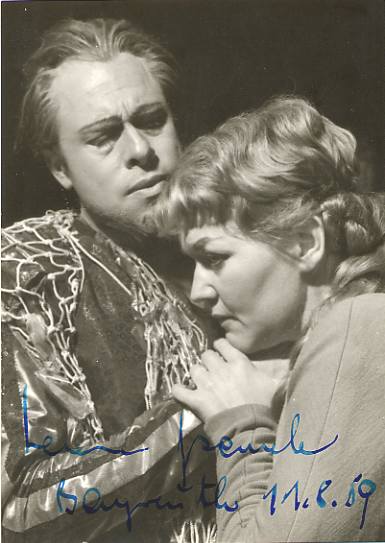

career! LR: This was, as we call it, my

Schicksals,

my destiny

part. When I was a young singer — and

I was also once a young

singer, a beginner! — when

German theaters asked me

to come for an engagement and said, "What do you want to sing?" I

always asked for Senta and Sieglinde because I thought these parts were

written for

me, for my voice, for my temperament, for my whole being. I sang

them for many, many years, and it was with a very heavy heart that I

gave them up because I

couldn't do them as I did them. That's the secret. You have

to know when to give up a part, when to say

goodbye, even if you love it like nothing else. You have to be

honest with yourself and say, "Don't do it

anymore; don't destroy your own legend."

LR: This was, as we call it, my

Schicksals,

my destiny

part. When I was a young singer — and

I was also once a young

singer, a beginner! — when

German theaters asked me

to come for an engagement and said, "What do you want to sing?" I

always asked for Senta and Sieglinde because I thought these parts were

written for

me, for my voice, for my temperament, for my whole being. I sang

them for many, many years, and it was with a very heavy heart that I

gave them up because I

couldn't do them as I did them. That's the secret. You have

to know when to give up a part, when to say

goodbye, even if you love it like nothing else. You have to be

honest with yourself and say, "Don't do it

anymore; don't destroy your own legend." LR: Well, if you ask me,

it's always difficult to talk about

oneself, but I think I never portray anything. I had a very long

interview last week for

television in Austria. There's a very famous program called

"Zeitzeugen," "Time-witnesses." That's how

old I am. [With a slightly derisive tone] Some honor!

So they asked me, "You are famous for your outgoing personality

onstage; how do you do it? What do you do?" My

answer was, "I don't know!" Honestly, I swear to God, I do not

know. Of course I know the part, I know the stories, I read

books, everything; but when I go on stage, I change. Of course

I'm not a

murderess, but the character is in me. I

really am not the type who thinks about things on stage. If

I hear the music, I'm absolutely involved. I'm the

character; I think I am the character, and sometimes after

a performance — even a

concert — you have to wake

me

up! It's like another world. This is not on purpose; it

does it. That's the only explanation I can give you.

LR: Well, if you ask me,

it's always difficult to talk about

oneself, but I think I never portray anything. I had a very long

interview last week for

television in Austria. There's a very famous program called

"Zeitzeugen," "Time-witnesses." That's how

old I am. [With a slightly derisive tone] Some honor!

So they asked me, "You are famous for your outgoing personality

onstage; how do you do it? What do you do?" My

answer was, "I don't know!" Honestly, I swear to God, I do not

know. Of course I know the part, I know the stories, I read

books, everything; but when I go on stage, I change. Of course

I'm not a

murderess, but the character is in me. I

really am not the type who thinks about things on stage. If

I hear the music, I'm absolutely involved. I'm the

character; I think I am the character, and sometimes after

a performance — even a

concert — you have to wake

me

up! It's like another world. This is not on purpose; it

does it. That's the only explanation I can give you. LR: That's another

question. Szymanowski I liked very

much, but was not so modern. The very extreme parts, the

very extreme music is, of course, difficult. I couldn't do

it; I couldn't. Really! Not because of my age, but

I never could have done it. That's a good

question. Maybe sometimes they go too far. The

time has changed, the music has changed. Everything!

But not the vocal cords! That's the difference. You can

change the hearing... you

hear different, you see different, you listen

different, but the vocal cords are same like they were 200

years ago. They haven't changed.

LR: That's another

question. Szymanowski I liked very

much, but was not so modern. The very extreme parts, the

very extreme music is, of course, difficult. I couldn't do

it; I couldn't. Really! Not because of my age, but

I never could have done it. That's a good

question. Maybe sometimes they go too far. The

time has changed, the music has changed. Everything!

But not the vocal cords! That's the difference. You can

change the hearing... you

hear different, you see different, you listen

different, but the vocal cords are same like they were 200

years ago. They haven't changed. LR: I don't know; I liked

Carol [Fox, one of the founders of Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1954] very

much. I

don't sing so much anymore... And after my sickness

— I was so sick

— I had

hepatitis B, you know. It was not painful,

but you can't walk; it tires you and I was exhausted. It's only

four months now, and they say

it takes a year to recover. I did this concert only for Jimmy

[Levine]; I love him, and he likes me. I said to him, "Without

you I wouldn't have done this," and Chrysothemis is one of my favorites

— in

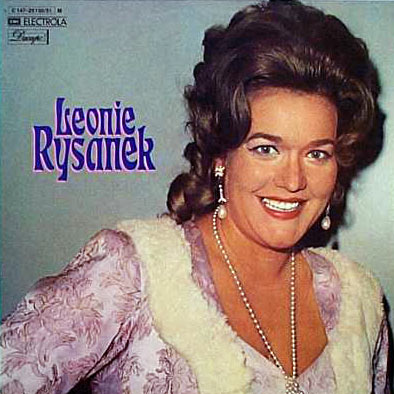

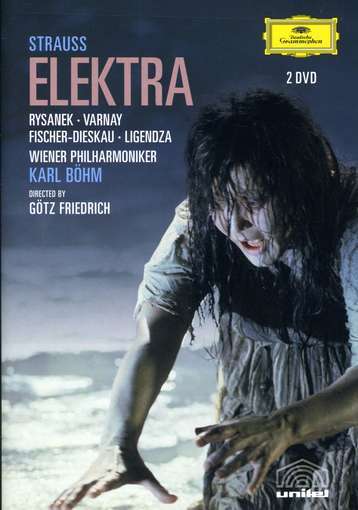

spite of my Elektra. I did the movie, you know, with Böhm

[photo of cover at right].

LR: I don't know; I liked

Carol [Fox, one of the founders of Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1954] very

much. I

don't sing so much anymore... And after my sickness

— I was so sick

— I had

hepatitis B, you know. It was not painful,

but you can't walk; it tires you and I was exhausted. It's only

four months now, and they say

it takes a year to recover. I did this concert only for Jimmy

[Levine]; I love him, and he likes me. I said to him, "Without

you I wouldn't have done this," and Chrysothemis is one of my favorites

— in

spite of my Elektra. I did the movie, you know, with Böhm

[photo of cover at right].Leonie Rysanek, Operatic Soprano, Dies at 71 By ANTHONY TOMMASINI Published in The New York Times, March 9, 1998 Leonie Rysanek, the Austrian dramatic soprano whose illustrious international career spanned nearly 40 years, died on Saturday at a hospital in Vienna, the city of her birth, where she lived all her life. She was 71. She had been battling bone cancer, according to Peter S. Diggins, an artists' representative in New York and a longtime friend. It was during Ms. Rysanek's final performances at the Metropolitan Opera in late 1995 and early 1996 in a new production of Tchaikovsky's ''Pique Dame'' that she received confirmation of her cancer diagnosis. But she told few people about it. The scope of Ms. Rysanek's career was remarkable: she sang with the conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler during his final years in the early 1950's, and with the tenor Jussi Bjoerling in his prime. Yet she was still singing ardently in the early 1990's. She possessed a gleaming, refulgent soprano voice with an especially powerful top and a rich middle range, ideal for roles like Wagner's Sieglinde and Senta, Strauss's Chrysothemis, and Beethoven's Leonora. Her full-voiced high notes could slice through the thickness of any Strauss orchestra. In her early days, her low voice was often criticized as patchy. But as she matured, her sound darkened and deepened, and she successfully took on lower-set roles like Wagner's Kundry in ''Parsifal.'' Ms. Rysanek's work was equally prized for its dramatic and musical intensity. Speaking of Ms. Rysanek at the time of her Met farewell, the conductor James Levine, a frequent colleague, said such longevity was striking for a singer of her fervor. ''She had a fire burning in her at all times,'' Mr. Levine said. ''It's remarkable for someone to combine such intensity with a voice of such resiliency and range,'' he added. ''Somehow there is a very womanly, soft-textured quality in Leonie's singing, even in its most forceful moments.'' Her approach to singing was not classically beautiful. Reporting on her 25th-anniversary Met gala in 1984, when she sang Kundry in Act II of ''Parsifal'' and Sieglinde in Act I of ''Walkure'' in a concert with Mr. Levine conducting, The New York Times critic John Rockwell wrote that Ms. Rysanek ''has never been a singer who stresses an even vocal line and abstract bel-canto virtues. She is an Expressionistic actress, given to splintering significant words under the stress of emotion and to wrenching her body and chopping her arms in a way that inevitably distorts her singing. But the result, a few mannerisms aside, is not the disruption of the music but the enhancement of the drama.'' Ms. Rysanek credited her longevity to careful pacing; even at the height of her career, she never sang more than 45 or so performances a year. But, in an interview with The Times on the occasion of her Met farewell, she also cited her ability to say no to the most taxing roles. And, in a way, she explained, the presence of her colleague Birgit Nilsson as the reigning dramatic soprano of her day, fortified her own resolve. ''Yes, I was asked to sing Brunnhilde,'' she said. ''But there was always Birgit, wonderful Birgit, next to me. She was my Brunnhilde, my Elektra. She was so wonderful in these parts. . . . Even Birgit asked, 'Why don't you sing Turandot?' I said, 'Because of you.' Maybe's it's Birgit who saved my voice.'' Ms. Rysanek was born in Vienna on Nov. 14, 1926, one of six children of a Czech father, a stonecutter, later a chauffeur, and an Austrian mother. As a adolescent during the war years, Ms. Rysanek had to work in a munitions factory. She aspired to be an actress. But her oldest brother, who had a pleasant baritone voice, encouraged her to take her singing seriously. She entered the Vienna Academy at 16, where she studied with Alfred Jerger, and later, Rudolf Grossmann, a baritone who became her first husband. The couple later divorced. Her professional debut was at Innsbruck in 1949 as Agathe in Weber's ''Der Freischutz.'' But international acclaim came in 1951, when she sang Sieglinde in the first postwar production at Bayreuth, Germany, of Wagner's ''Ring.'' Her American debut was in 1956 with the San Francisco Opera as Senta. |

| Obituary: Leonie Rysanek By Elizabeth Forbes The Independent, Monday, 9 March 1998 WHEN THE Bayreuth Festival re-opened in 1951 after the Second World War, the role of Sieglinde in Die Walkure was sung by a 24-year- old Viennese soprano, Leonie Rysanek. Everyone in the audience, myself included, was totally captivated - perhaps stunned is a better world - by the singer, whose glorious voice was matched by an attractive appearance and great dramatic ability. At that time Rysanek had been singing professionally for only two years: her career lasted for another astonishing four and a half decades, and though her voice and repertory naturally changed, the quality of her singing and acting never lapsed from the high standard of those early years. In Vienna, Munich, Berlin, San Francisco and New York, she sang a huge variety of roles, mainly German, but Italian as well: unfortunately she did not often appear in London, but Covent Garden heard her as Chrysothemis in Elektra, as Sieglinde, Tosca and the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier. Leonie Rysanek was born in Vienna of a musical family and her earliest ambition was to be a singing actress. She studied at the Vienna Conservatory with the baritone Alfred Jerger, and Rudolf Grossmann, whom she married in 1950. Meanwhile she made her concert debut in 1948 and her operatic debut in 1949 at Innsbruck as Agathe in Der Freischutz. In 1950 she moved to Saarbrucken, and two years later, after her triumphant appearance at Bayreuth, to the Bavarian State Opera in Munich. Here the long love affair between the soprano and the operas of Richard Strauss began. Her repertory included Arabella, Ariadne, the Empress in Die Frau ohne Schatten, the title role of Die Agyptische Helena, Salome, Chrysothemis and later Elektra, as well as Danae in Die Liebe der Danae, which she sang with the Munich company at Covent Garden in 1953. The following year she returned to sing Chrysothemis with the resident company, and also sang that role at La Scala. In 1954 Rysanek joined the Vienna State Opera, singing many of her Strauss roles there, as well as Wagner and Verdi. She made her US debut in 1956 at San Francisco as Senta in Der fliegende Hollander, followed over the next four years by Sieglinde, Aida, Turandot, Amelia in Un ballo in maschera, Leonora in La forza del destino, Elisabeth in Tannhauser and Lady Macbeth, the role in which she made an unscheduled debut at the Metropolitan in 1959, when Maria Callas cancelled her appearance in Verdi's opera. New York instantly took the soprano in its heart, and she returned there year after year. Her roles included Fidelio, the Marshallin, Salome, Elizabeth de Valois in Don Carlos, Abigaille in Nabucco, Tosca and many others. Rysanek returned to Bayreuth after many years' absence in 1982 to sing Kundry in the centenary performers of Parsifal. During the 1980s and 1990s she took on a whole new repertory of mezzo roles, including the Kostelnicka in Jenufa, Herodias in Salome, Ortrud in Lohengrin and Kabanicha in Katya Kabanova. However, the most successful of these later roles were Klytemnestra in Elektra and the Countess in The Queen of Spades. These may have been primarily dramatic triumphs, but the vocal achievements, particularly as Klytemnestra, were also amazing. Rysanek gave her farewell performance at the Met on 2 January 1996 as the Countess. On 25 August she took her farewell from the operatic stage at Salzburg as Klytemnestra, singing the role, as she had always sung every role, as beautifully and as meaningfully as she could. Leonie Rysanek made many fine recordings. The Strauss discs manage to catch the incredible way in which her voice could soar up into the stratosphere, as Helen, Chrysothemis, Ariadne and, most notably of all, as the Empress. Her Senta, Sieglinde and Elsa are well represented, while in the Italian repertory, she excels as Aida, Desdemona in Otello and as Lady Macbeth, probably her best Italian role. Leonie Rysanek, operatic soprano: born Vienna 14 November 1926; married 1950 Rudolf Grossmann (marriage dissolved), 1968 Ernst Gausmann; died Vienna 7 March 1998. |

This interview was recorded in a dressing room backstage in the

Pavillion of the Ravinia Festival in Highland Park, IL, (the summer

home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra) on June 25,

1986. Portions (along with recordings)

were used on WNIB later that year, and again in 1991 and 1996. This

transcription was

made and posted on this

website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.