|

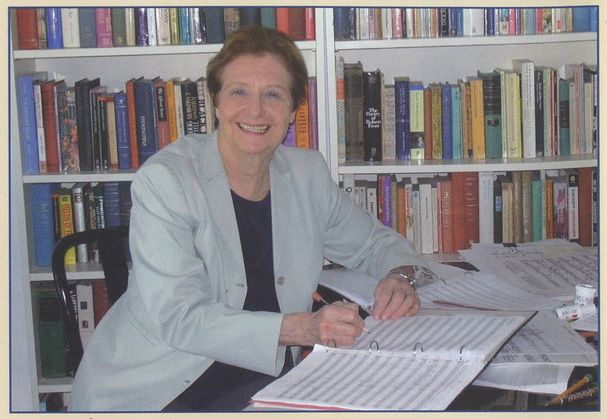

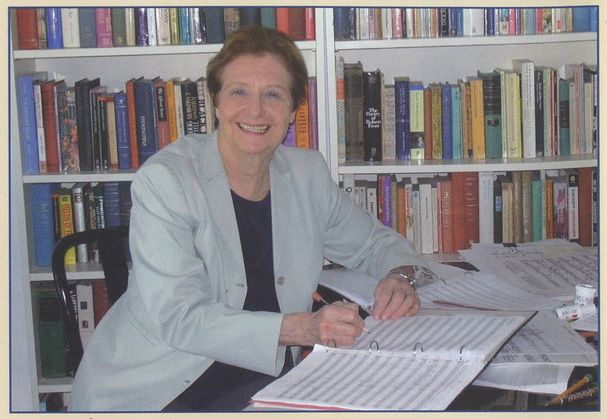

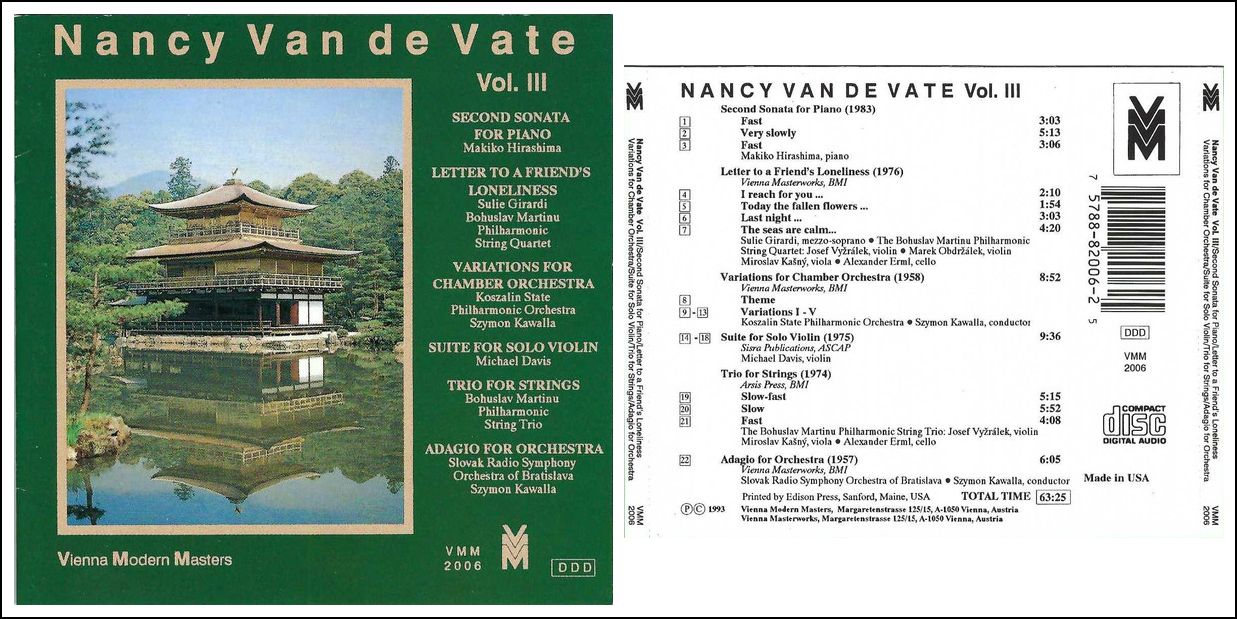

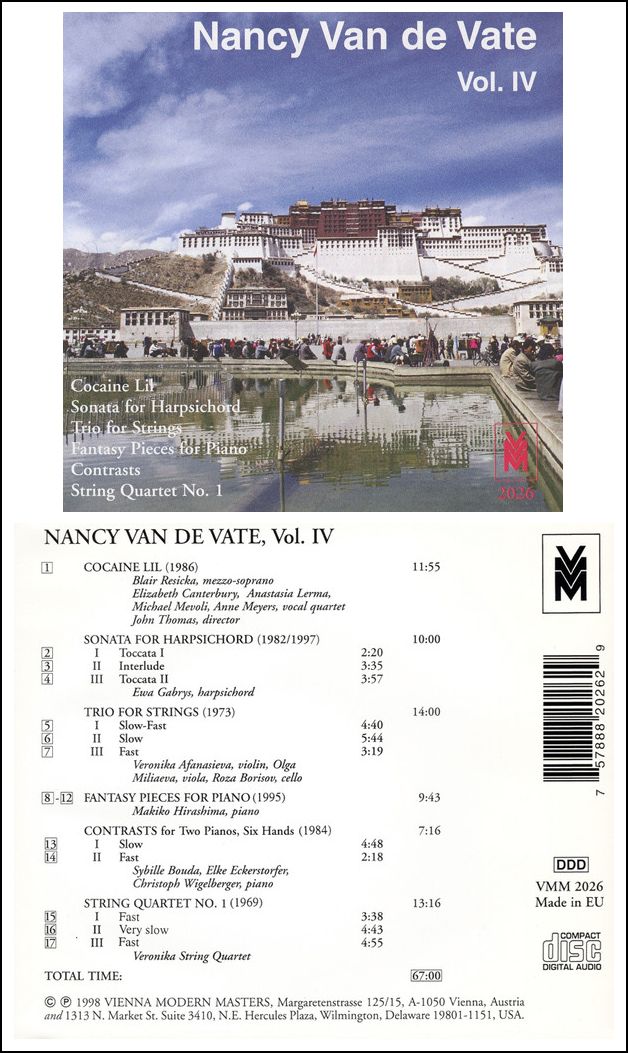

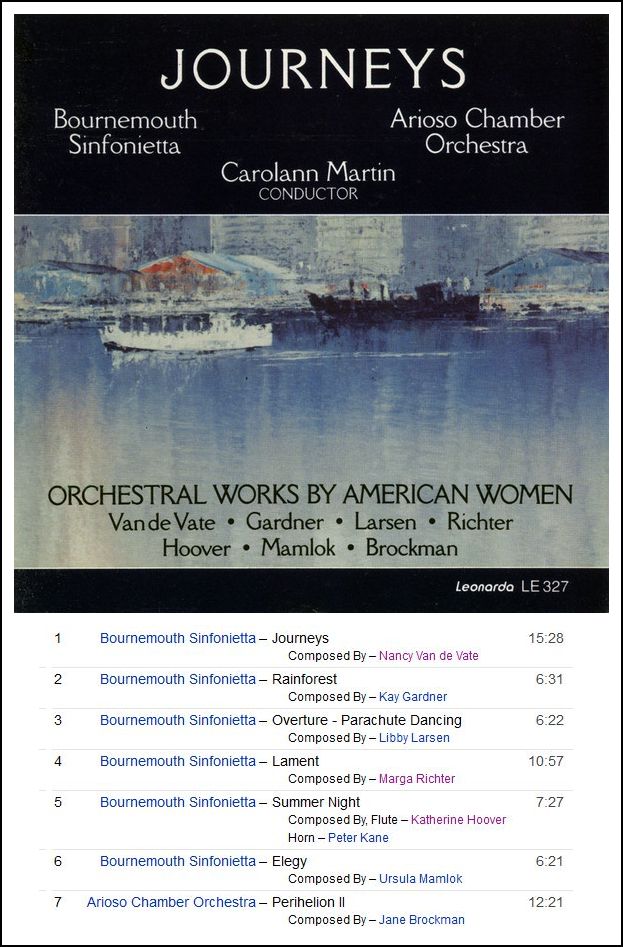

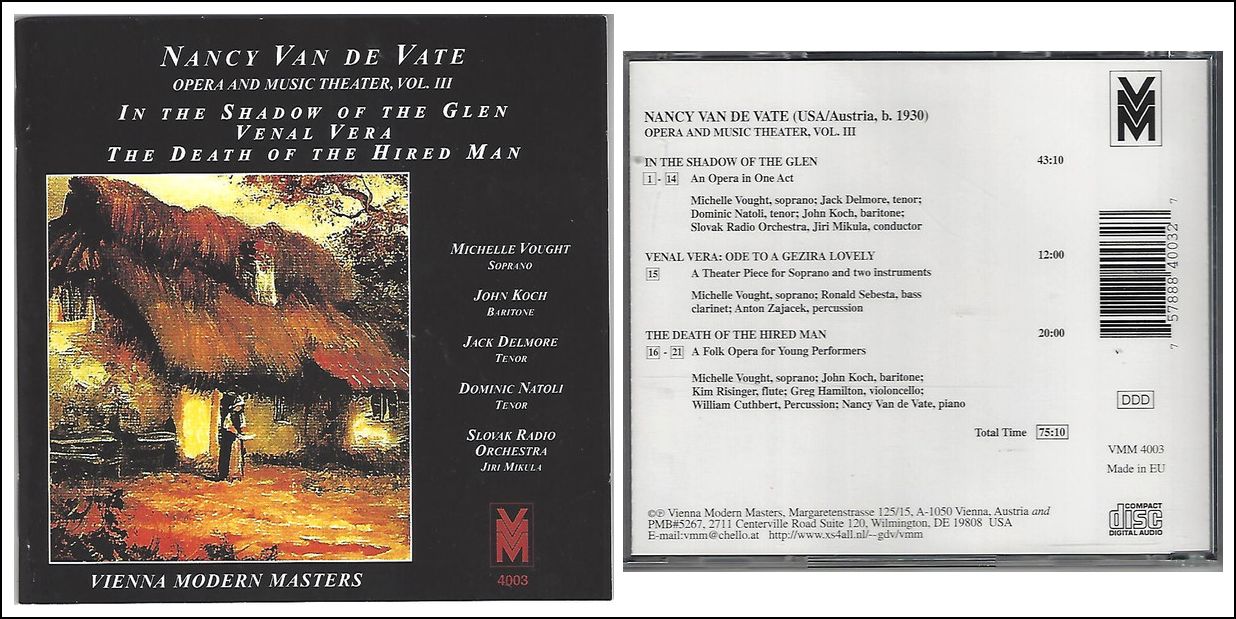

Nancy Van de Vate was born in Plainfield, New Jersey December 30, 1930. She studied piano at Eastman School of Music and music theory at Wellesley College and completed graduate degrees in music composition at the University of Mississippi and Florida State University. She later pursued further studies in electronic music at Dartmouth College and the University of New Hampshire and is known worldwide for her music in the large forms. Her first professional performance (1958) was of the Adagio for orchestra. During the early part of her career she taught at various North American universities and worked as a violist and pianist.

In 1975, Van de Vate founded the League of Women Composers and

served as chairperson until 1982. It was later renamed the International League

of Women Composers, now part of the International Alliance for Women in Music. Her music has appeared

frequently on major international music festivals including the WINTER

MUSIC NIGHTS in Bulgaria (1996), SORO MUSIC FESTIVAL in Denmark (1994),

VIENNA MUSIC SUMMER (1992), ULTIMA 92 in Norway (1992), JAPAN SOCIETY

FOR CONTEMPORARY MUSIC (1991), WRATISLAVIA CANTANS in Wroclaw, Poland

(1990), ASPEKTE in Salzburg (1989 and 1990), MUSICA VIVA in Munich (1989),

and POZNAN SPRING in Poland (1984), among others. She has received commissions

and awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Maryland State

Arts Council, the American Association of University Women, Meet the

Composer, the Money for Women Fund, the Austrian Foreign Ministry, the

City of Vienna, and others. She has been a Resident Fellow at Yaddo,

the MacDowell Colony, and Ossabaw Island in the US, the Tyrone Guthrie

Centre at Annaghmakerrig (Ireland), the Brahmshaus (Baden-Baden, Germany),

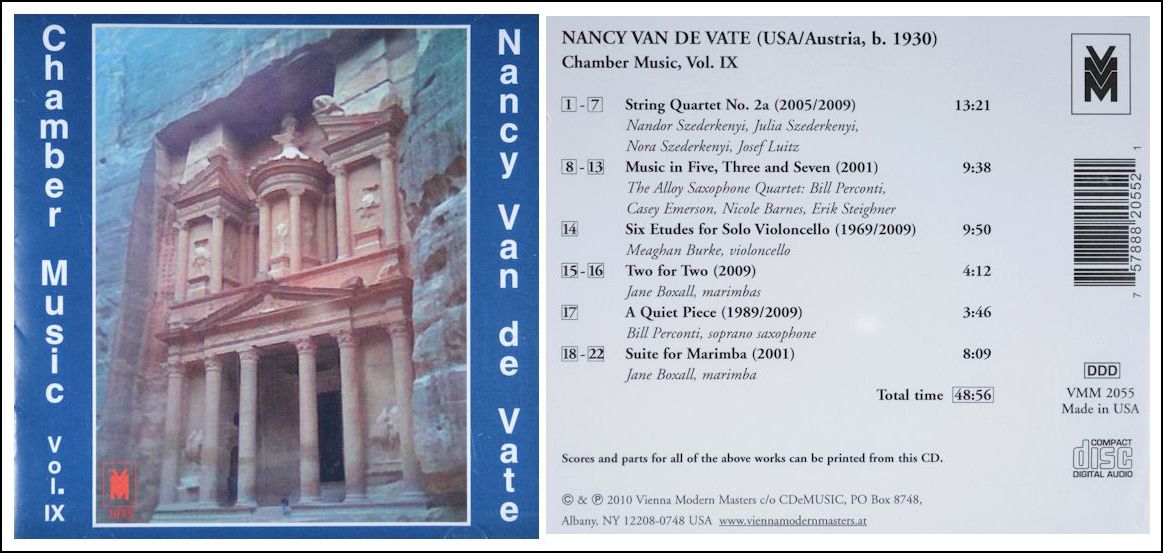

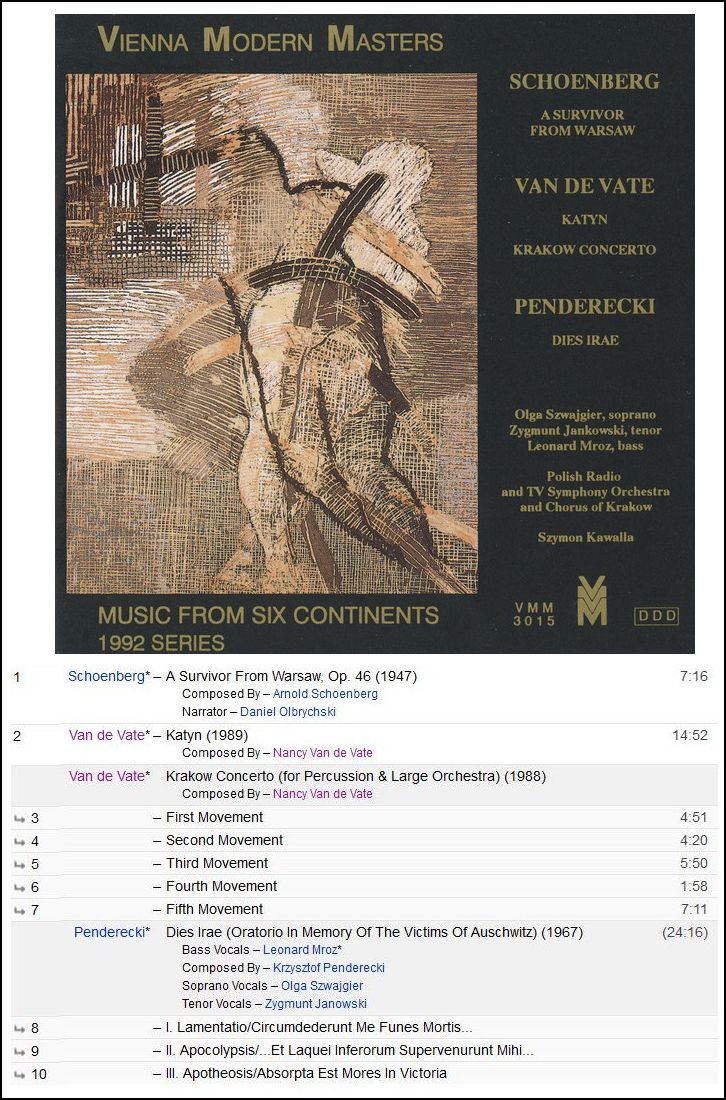

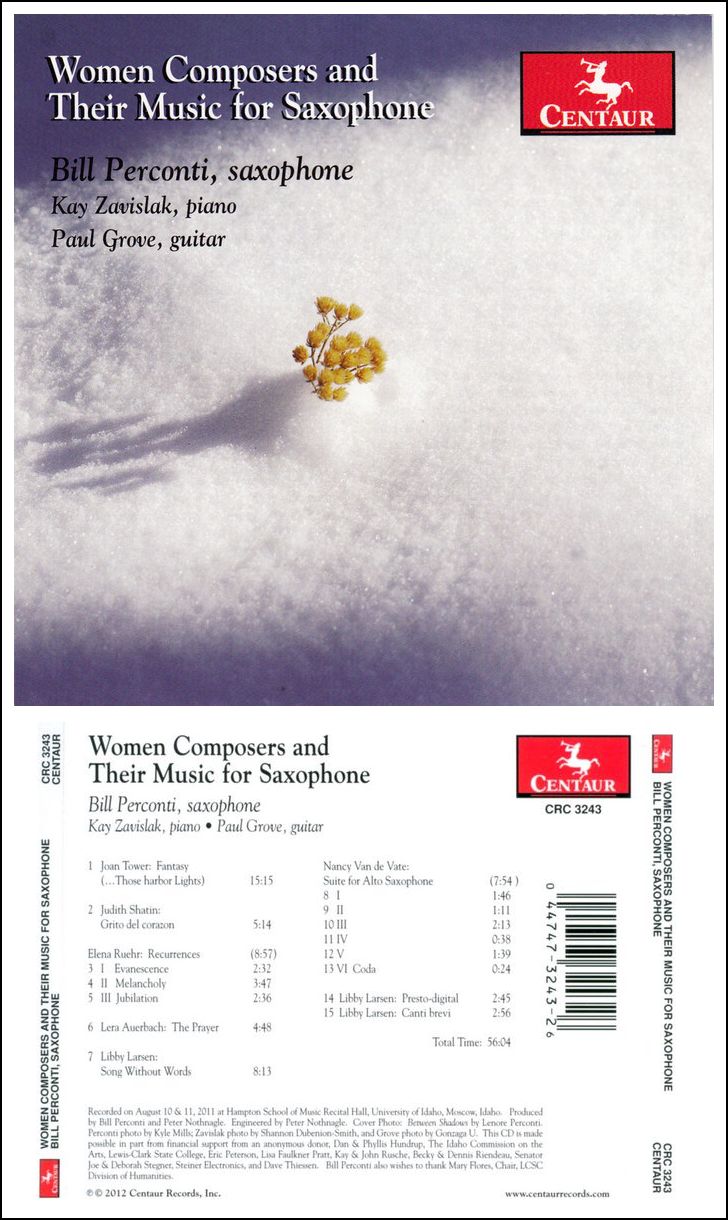

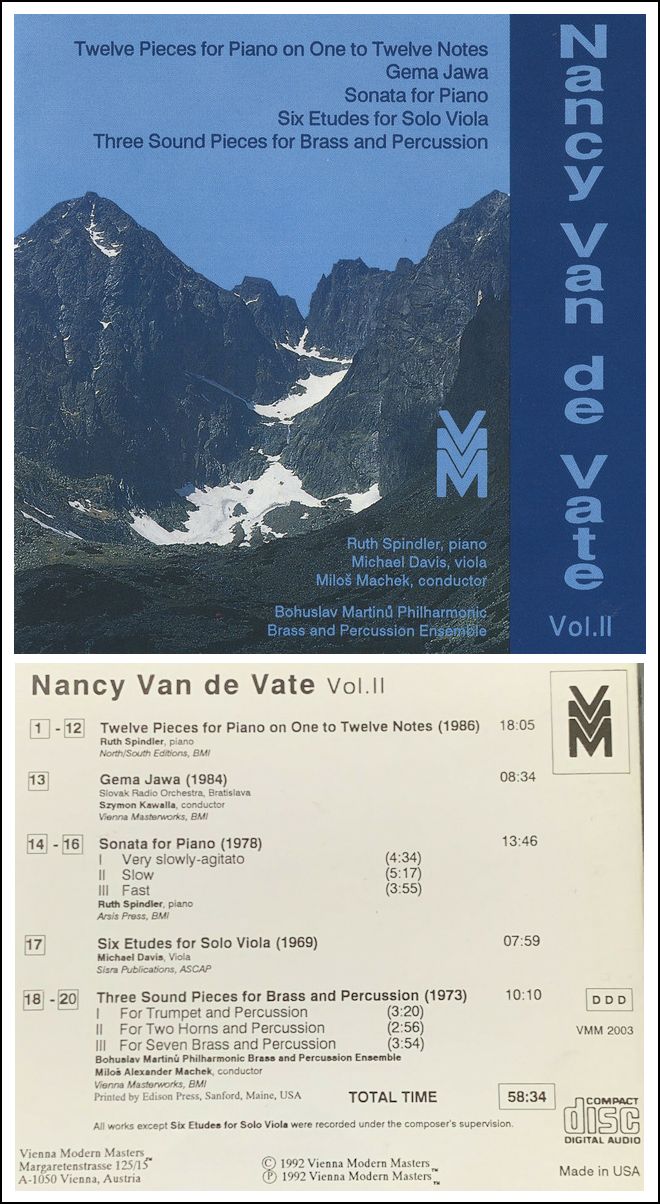

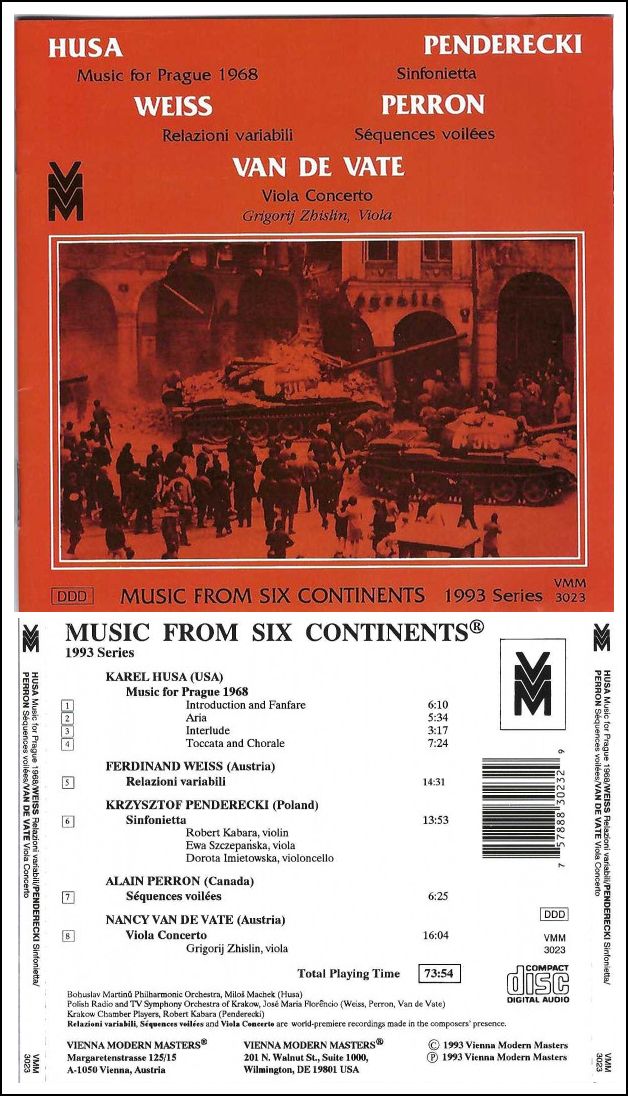

and the Kunstlerhaus Boswil (Switzerland). With 26 orchestral and orchestral-choral

works recorded to date, Van de Vate is one of the most recorded living

composers of orchestral music in the world. Her discography also includes

many recordings of chamber and solo works. Her entries in the Schwann

Opus and Bielefelder catalogs identify her as the world's most recorded

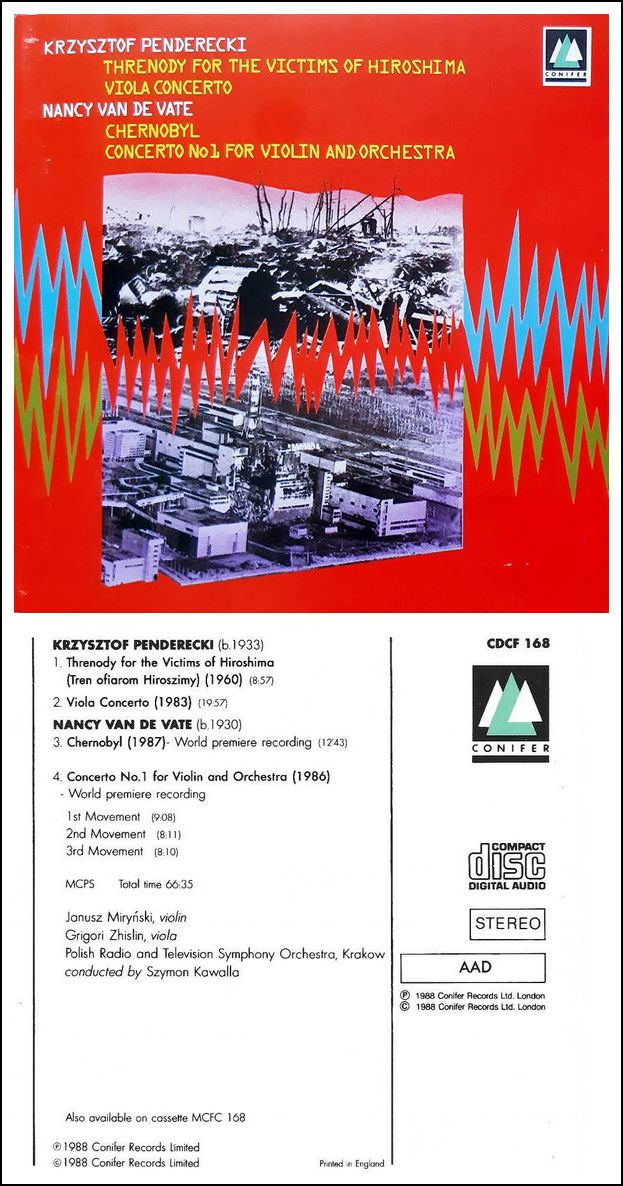

woman composer, living or dead. Chernobyl was nominated for the

1989 Koussevitsky International-Recording Award for the best new work

by a living composer in its first recording, and for the Pulitzer Prize

in 1998.

== Biography compiled from different sources

|

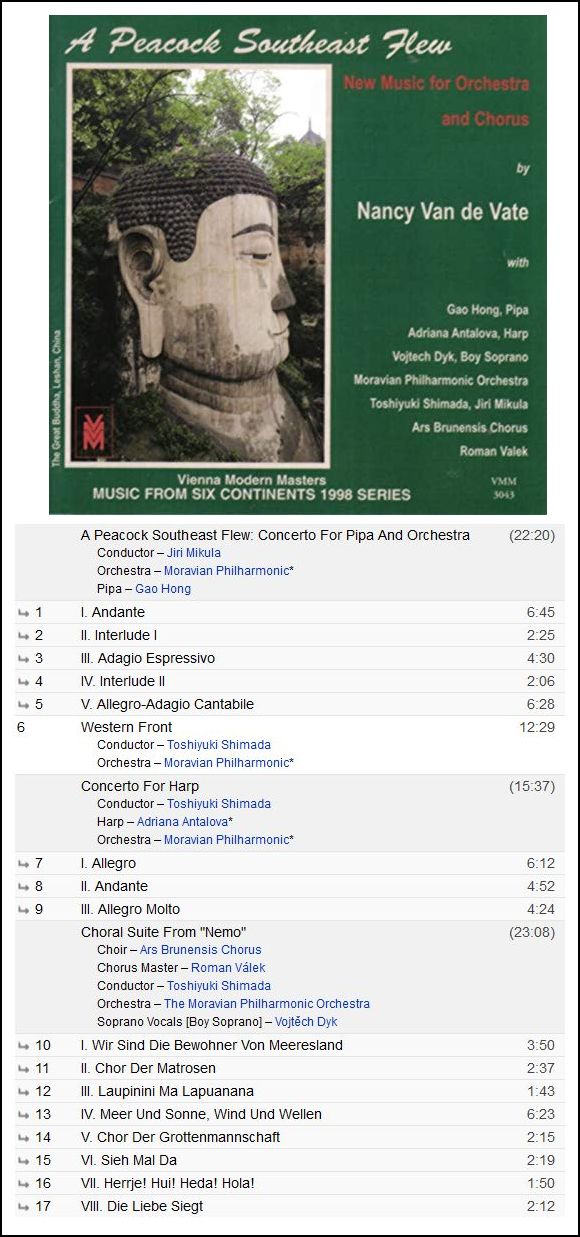

The Chinese pipa, a four-string plucked lute, descends from West and Central Asian prototypes and appeared in China during the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534). Traveling over ancient trade routes, it brought not only a new sound but also new repertoires and musical theory. Originally it was held horizontally like a guitar, and its twisted silk strings were plucked with a large triangular plectrum held in the right hand. The word pipa describes the plectrum’s plucking strokes: pi, “to play forward,” pa, “to play backward.” During the Tang dynasty (618–907), musicians gradually began using their fingernails to pluck the strings, and to hold the instrument in a more upright position. First thought to be a foreign and somewhat improper instrument, it soon won favor in court ensembles but today it is well known as a solo instrument whose repertoire is a virtuosic and programmatic style that may evoke images of nature or battle. Because of its traditional association with silk strings, the pipa is classified as a silk instrument in the Chinese bayin (eight-tone) classification system, a system devised by scholars of the Zhou court (1046–256 B.C.) to divide instruments into eight categories determined by materials. However, today many performers use nylon strings instead of the more expensive and temperamental silk. Pipas have frets that progress onto the belly of the instrument, and the pegbox finial may be decorated with a stylized bat (symbol of good luck), a dragon, a phoenix tail, or decorative inlay. The back is usually plain since it is unseen by an audience. Text by J. Kenneth Moore

Department of Musical Instruments Metropolitan Museum of Art

Unlike tubular bells, another form of chime, the chimes on a Mark tree do not produce a definite pitch, as they produce inharmonic (rather than harmonic) spectra. The mark tree is named after its inventor, studio percussionist Mark Stevens. He devised the instrument in 1967. When he could not come up with a name, percussionist Emil Richards dubbed the instrument the Mark tree. The mark tree should not be confused with two similar instruments:

|

© 1990 & 1998 Bruce Duffie

The first conversation was recorded on the telephone on August 30, 1990. The second was held in Chicago on August 27, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in December of 1990, 1995, and 2000; and on WNUR in 2004. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.