AB: Long ago I

decided — that

was in ’63 — that I can’t do

everything, so I haven’t gone back to Latin America. I had

decided quite a few years ago that four tours in Australia were enough

and that I shall skip this very distant island, as well as New

Zealand. I’m going to Japan about every third year, and to

Israel. I keep in touch with certain European capitals, and

certain American cities. As my availability in the United States

is very limited, it is very hard sometimes to know what to do.

That is how to keep in touch with the great orchestras, for

instance. But last year, I had made an entirely orchestral tour,

for once. I was with all the great orchestras except

Chicago.

AB: Long ago I

decided — that

was in ’63 — that I can’t do

everything, so I haven’t gone back to Latin America. I had

decided quite a few years ago that four tours in Australia were enough

and that I shall skip this very distant island, as well as New

Zealand. I’m going to Japan about every third year, and to

Israel. I keep in touch with certain European capitals, and

certain American cities. As my availability in the United States

is very limited, it is very hard sometimes to know what to do.

That is how to keep in touch with the great orchestras, for

instance. But last year, I had made an entirely orchestral tour,

for once. I was with all the great orchestras except

Chicago. AB: I’m very far

from remembering all of them, and as

far as my offspring goes, I’m sometimes glad if it leaves me and they

lead their own lives! [Laughs] I would have to listen again to

all those records and then give you an account of what I like and what

I dislike. There may be some old recordings, at least some

movements, which I still like or which I find convincing in their own

terms. And there may be some recent recordings that I dislike.

AB: I’m very far

from remembering all of them, and as

far as my offspring goes, I’m sometimes glad if it leaves me and they

lead their own lives! [Laughs] I would have to listen again to

all those records and then give you an account of what I like and what

I dislike. There may be some old recordings, at least some

movements, which I still like or which I find convincing in their own

terms. And there may be some recent recordings that I dislike. AB: Well, to answer

this question you should have

studied composition yourself and composed enough to be able to look at

other works that you deal with from a composer’s point of view.

This is a suggestion to all younger performers that I meet, if they ask

me what they should do. The first question is: do you

compose? Do you have a good understanding of composition?

Did you put pieces together yourself? It helps to just get at

least the first degree of feeling to know how a piece hangs together

and why it hangs to together; then gradually, in dealing with

masterpieces, to find out why certain pieces are different from others,

and how masterworks of the same composer are different. They

wouldn’t be masterworks otherwise. They contribute something that

the composer has not done elsewhere. To characterize them, to

find out this difference, is one of the wonderful tasks of the

performer — not to have a stereotyped approach to what the composer has

done, but within the very large world of a great composer, to define

those pieces. And it is easier to define them if you play cycles,

because you have them next to one another. You try, as in a

much-performed work of variations, to set the variations apart from one

another.

AB: Well, to answer

this question you should have

studied composition yourself and composed enough to be able to look at

other works that you deal with from a composer’s point of view.

This is a suggestion to all younger performers that I meet, if they ask

me what they should do. The first question is: do you

compose? Do you have a good understanding of composition?

Did you put pieces together yourself? It helps to just get at

least the first degree of feeling to know how a piece hangs together

and why it hangs to together; then gradually, in dealing with

masterpieces, to find out why certain pieces are different from others,

and how masterworks of the same composer are different. They

wouldn’t be masterworks otherwise. They contribute something that

the composer has not done elsewhere. To characterize them, to

find out this difference, is one of the wonderful tasks of the

performer — not to have a stereotyped approach to what the composer has

done, but within the very large world of a great composer, to define

those pieces. And it is easier to define them if you play cycles,

because you have them next to one another. You try, as in a

much-performed work of variations, to set the variations apart from one

another. BD: Does that please

you, or merely amuse

you?

BD: Does that please

you, or merely amuse

you? BD: How can you

play Mozart all the time and not be

an optimist?

BD: How can you

play Mozart all the time and not be

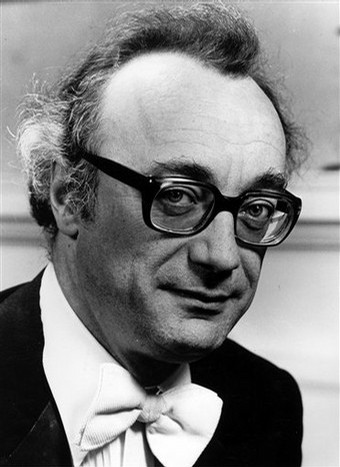

an optimist?Now celebrating his 60th year of performing before the public, Alfred Brendel is recognized by audiences the world over for his legendary ability to communicate the emotional and intellectual depths of whatever music he performs. A supreme master of his art, his accomplishments as an interpreter of the great composers have earned him a place among the world's most revered musicians.  Having spent the earlier part of this season in the

concert halls of Vienna, Berlin, London, Budapest, and other musical

capitals of Europe, Mr. Brendel appears on his annual North American

tour, performing Mozart K.491 with James Levine and the Metropolitan

Opera Orchestra at Carnegie Hall; Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 3 with

Kent Nagano and the Montreal Symphony, with Franz Welser-Möst and

the Cleveland Orchestra, with Osmo Vänskä and the Minnesota

Orchestra, and with Stéphane Denève and the Pittsburgh

Symphony Orchestra. He appears in recital at Carnegie Hall, for the

Celebrity Series of Boston, with Chicago Symphony Presents and at the

Washington Performing Arts Society. Having spent the earlier part of this season in the

concert halls of Vienna, Berlin, London, Budapest, and other musical

capitals of Europe, Mr. Brendel appears on his annual North American

tour, performing Mozart K.491 with James Levine and the Metropolitan

Opera Orchestra at Carnegie Hall; Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 3 with

Kent Nagano and the Montreal Symphony, with Franz Welser-Möst and

the Cleveland Orchestra, with Osmo Vänskä and the Minnesota

Orchestra, and with Stéphane Denève and the Pittsburgh

Symphony Orchestra. He appears in recital at Carnegie Hall, for the

Celebrity Series of Boston, with Chicago Symphony Presents and at the

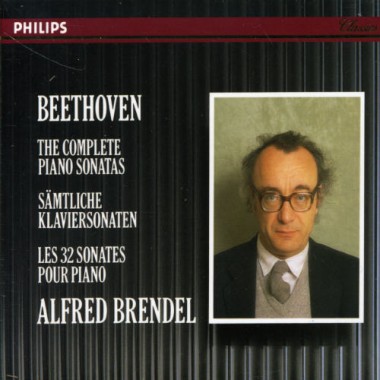

Washington Performing Arts Society.Mr. Brendel has performed with virtually all leading orchestras and conductors. He has appeared in the major cultural centers of Europe and the Far East, and his annual tours of North America have taken him from coast to coast. In recent seasons Mr. Brendel has performed with the Boston Symphony, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Chicago Symphony with Daniel Barenboim conducting, the Minnesota Orchestra and Osmo Vänskä, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the inaugural season of the new Disney Hall. He is an annual visitor to Carnegie Hall, where in 1983 he became the first pianist since the legendary Artur Schnabel to play all 32 Beethoven sonatas. At Carnegie Hall in 1999, he appeared six times in just over three weeks to delight audiences with recitals, chamber music, lieder with baritone Matthias Goerne, poetry reading, and a Mozart concerto with James Levine and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Mr. Brendel's performance at Carnegie Hall the year before - on April 26, 1998 - marked the exact anniversary of his first public recital fifty years ago at the Kammermusiksaal in Graz, Austria. The same series of celebratory events took place later that year at the Lucerne Festival. Strongly identified for his performances of Mozart, Mr. Brendel marked the composer's 250th birth anniversary on January 27, 2006 with a special performance of Mozart's final piano concerto, K.595, with the Berlin Philharmonic and Simon Rattle at Carnegie Hall, which they performed together thereafter with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Alfred Brendel is one of the most prolific recording artists of all time, and for the past thirty years has recorded exclusively for Philips Classics. He is the first pianist to have recorded all of Beethoven's piano compositions and one of the few to have recorded the complete Mozart piano concertos. An extensive discography includes "The Art of Alfred Brendel," a deluxe limited-edition collection of his comprehensive and varied repertoire. His recent releases include a live recording of Schubert sonatas; the five Beethoven piano concertos with Simon Rattle and the Vienna Philharmonic (the fourth time Mr. Brendel has committed these works to disc); Mozart Concertos with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and Charles Mackerras; works by Haydn, Schubert and Liszt recorded live in Salzburg; and a series of discs devoted to the complete sonatas and other solo works of Mozart. Also recently released is a recording of the complete Beethoven sonatas for piano and cello with his son, cellist Adrian Brendel. He has won many prizes for his recordings, notably the Grand Prix du Disque, the Japan Record Academy Award, Gramophone's "Critics' Choice," the Edison Prize, and the Grand Prix de l'Académie du Disque Français. In 2001, Mr. Brendel received a Lifetime Achievement Award in Cannes at MIDEM, the world's largest recording industry's fair.  Mr. Brendel is well versed in the fields of literature,

language, architecture and films. In addition to his latest books,

Alfred Brendel on Music and Ausgerechnet Ich ("Me Of All People"), he

has published two collections of articles, lectures and essays. He is a

frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books, having written

articles on Mozart, Liszt and Schoenberg. Mr. Brendel's volumes of

poetry – "A collection of texts which can be numbered among the sparse

ranks of genuinely comic literature and which make their author

possibly ‘immortal.'" (Frankfurter Allegmeine Zeitung,) include One

Finger Too Many, published in the United States by Random House, and

Cursing Bagels, released in English by Faber and Faber. He has given

readings of his works in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, and in

many of the cultural capitals of Europe. Mr. Brendel is the subject of

the BBC documentary "Alfred Brendel - Man and Mask." Mr. Brendel is well versed in the fields of literature,

language, architecture and films. In addition to his latest books,

Alfred Brendel on Music and Ausgerechnet Ich ("Me Of All People"), he

has published two collections of articles, lectures and essays. He is a

frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books, having written

articles on Mozart, Liszt and Schoenberg. Mr. Brendel's volumes of

poetry – "A collection of texts which can be numbered among the sparse

ranks of genuinely comic literature and which make their author

possibly ‘immortal.'" (Frankfurter Allegmeine Zeitung,) include One

Finger Too Many, published in the United States by Random House, and

Cursing Bagels, released in English by Faber and Faber. He has given

readings of his works in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, and in

many of the cultural capitals of Europe. Mr. Brendel is the subject of

the BBC documentary "Alfred Brendel - Man and Mask."Born in Weissenberg, Moravia, Alfred Brendel spent his childhood traveling throughout Yugoslavia and Austria. His father, an architectural engineer, businessman and cinema director, also ran a resort hotel on the Adriatic. The younger Brendel began piano lessons at the age of six but, owing to the family's continuous travel, had to give up one piano teacher after another. In his teens, he attended the Graz Conservatory where he studied piano, composition and conducting. He also showed talent as a painter and, when he made his recital debut at the age of 17, an art gallery near the concert hall was showing a one-man exhibition of his watercolors. He discontinued formal piano studies soon after, preferring to attend occasional master classes, including those given by the famed pianist Edwin Fischer. To this day Mr. Brendel regards his untraditional musical background as something of an advantage. "Many times a teacher can be too influential," he says. "Being self-taught, I learned to distrust anything I hadn't figured out myself." Although Mr. Brendel's artistic interests as a young man did not focus on music alone, his winning the prestigious Busoni Piano Competition in Italy launched his career as a performing musician. He quickly established a reputation of unusual integrity and insight into the music of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann and Schubert, as well as the works of Liszt and several 20th century composers. Alfred Brendel is the recipient of honorary doctorates from Oxford, London, Sussex and Yale universities. He is only the third pianist in history to be named an honorary member of the Vienna Philharmonic, a distinction he shares with his illustrious predecessors, Emil von Sauer and Wilhelm Backhaus. Mr. Brendel has been awarded the Leonie Sonning Prize, the Furtwängler Prize for Musical Interpretation, London's South Bank Award, the Robert Schumann Prize presented in Zwickau, Schumann's birthplace; the Ernst von Siemens Prize and, most recently, "A Life for Music – the Artur Rubinstein Prize," presented by the Artur Rubinstein Cultural Association of Venice, Italy. In 1989 he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II for "Outstanding Services to Music in Britain," where he has made his home since 1972. (Biography from Colbert

Artists Management, Inc., January 2008)

|

This interview was recorded in the musicians’ lounge in

the basement of Orchestra Hall in Chicago on April 20, 1991.

Portions were used on WNIB

(along with musical examples) in 1996 and 1999. The transcription

was made in 2008 and posted on this

website in November of that year.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.