A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

Anner

Bylsma (Cello)

Born: February 17, 1934 - The Hague, the Netherlands  The Dutch cellist, Anner Bylsma [Bijlsma], received his first lessons from

his father, also a multi-talented musician. At the age of 16, he enrolled

at the Royal Conservatory, The Hague, to study with Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp,

principal cellist with the Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam. It was Boomkamp

who introduced Bylsma to the Baroque cello. Bylsma won the school's Prix d'excellence

in 1957, and after becoming the Netherlands Opera Orchestra's principal cellist,

he won first prize in the Casals Competition in Mexico in 1959.

The Dutch cellist, Anner Bylsma [Bijlsma], received his first lessons from

his father, also a multi-talented musician. At the age of 16, he enrolled

at the Royal Conservatory, The Hague, to study with Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp,

principal cellist with the Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam. It was Boomkamp

who introduced Bylsma to the Baroque cello. Bylsma won the school's Prix d'excellence

in 1957, and after becoming the Netherlands Opera Orchestra's principal cellist,

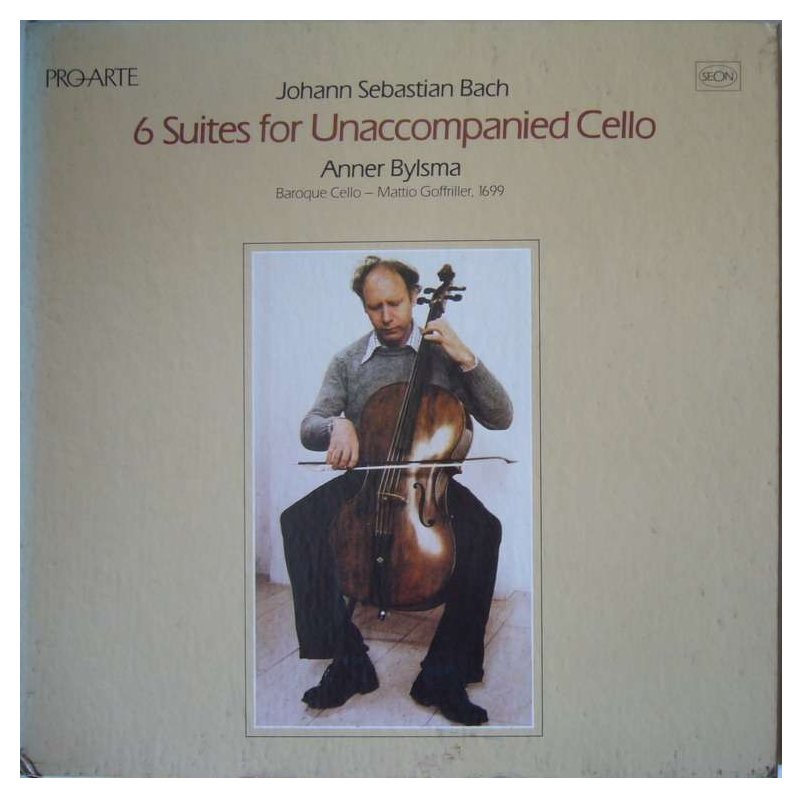

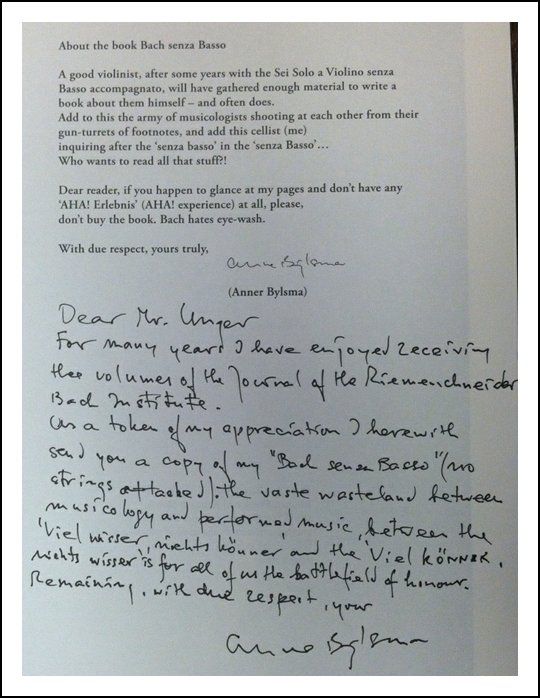

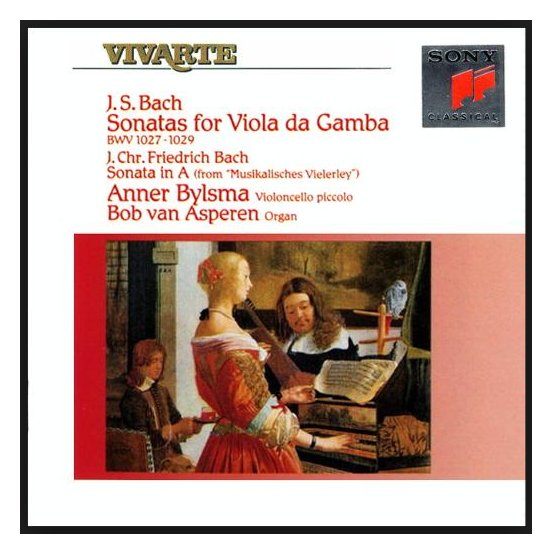

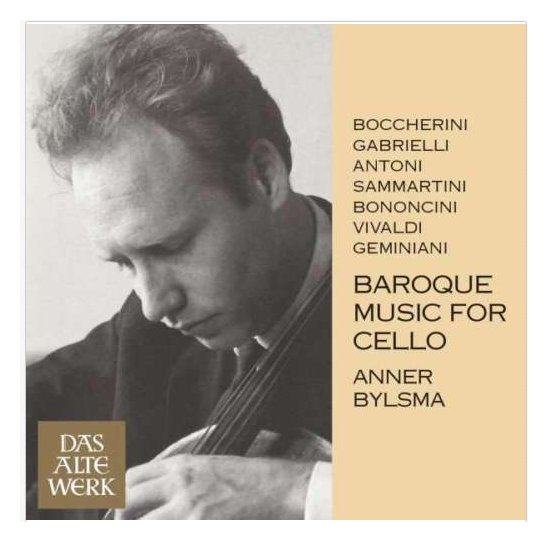

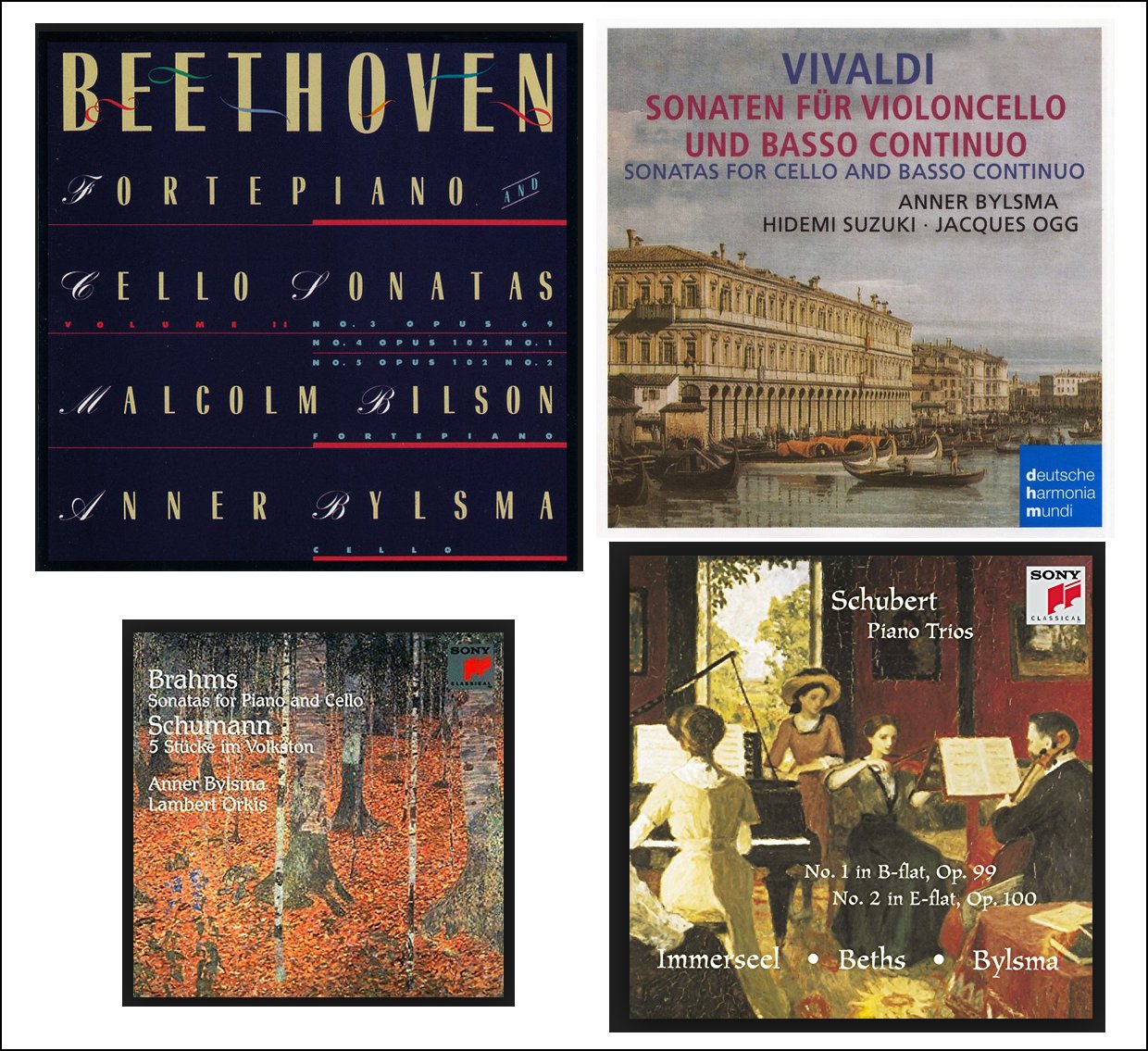

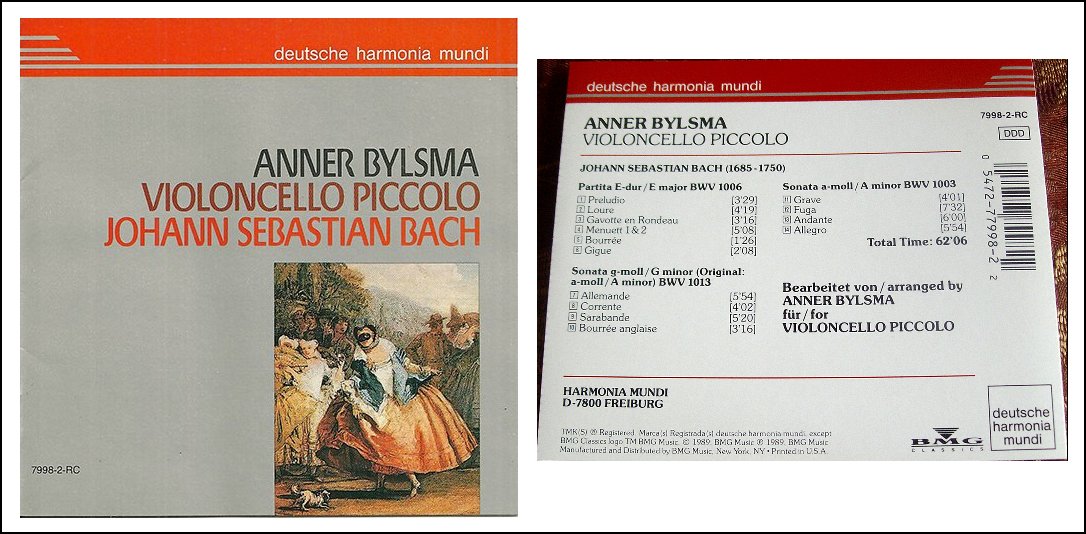

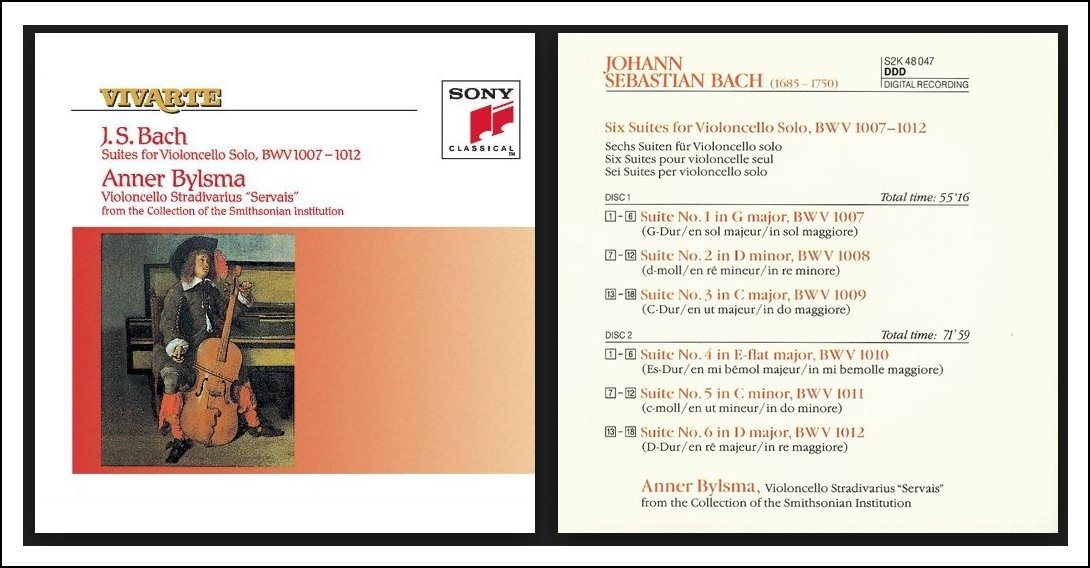

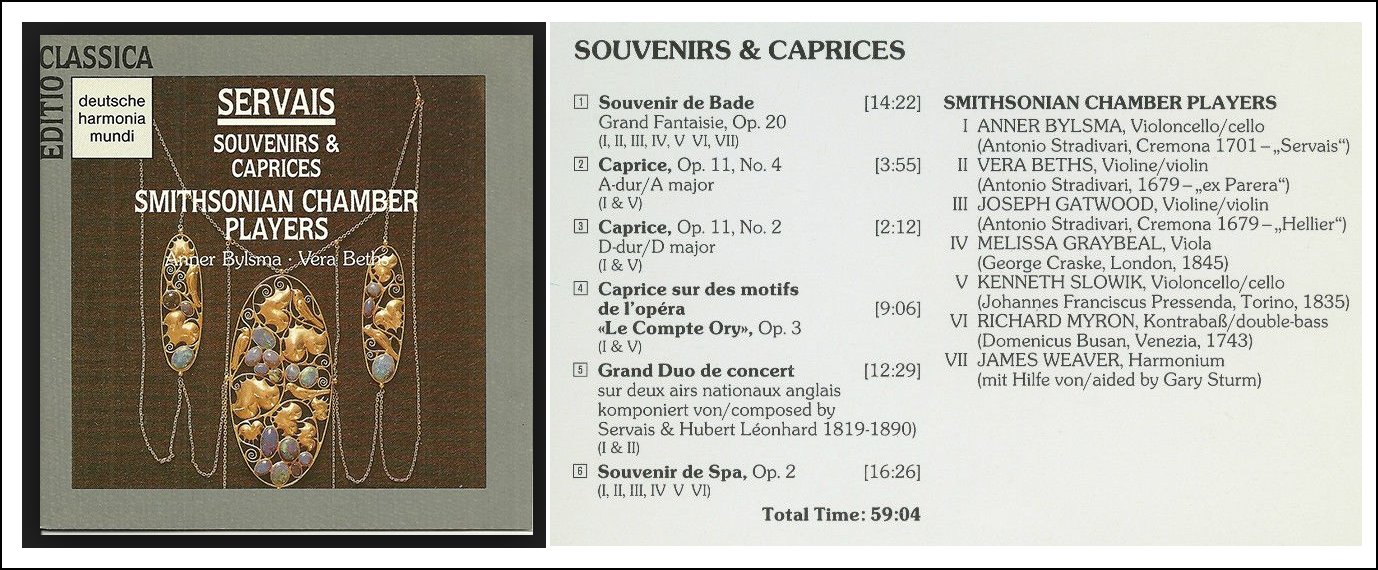

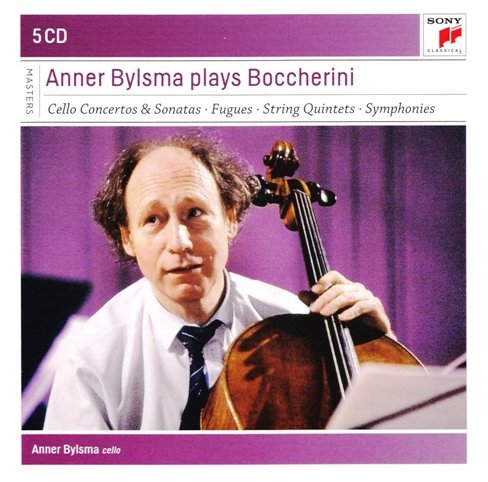

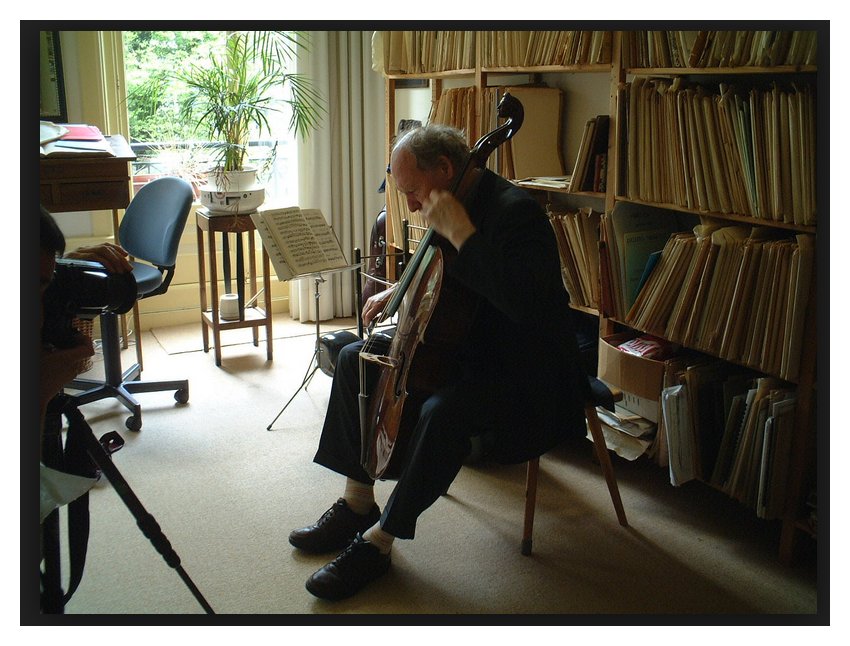

he won first prize in the Casals Competition in Mexico in 1959.Playing with impeccable technique and a beautiful, unadulterated tone, Bylsma is acknowledged as a master cellist, comfortable in a wide range of music on both both modern cello and period instrument cello in an historically informed Baroque style. As his father, he himself was principal cellist of the Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam for six years (from 1962 to 1968). He left the orchestra to devote his performing career to solo and chamber ensemble touring. He is one of the pioneers of the 'Dutch Baroque School', and rose to fame as a partner of period flutist Frans Brüggen (1934-2014) and harpsichordist Gustav Leonhardt (1928-2012), who toured extensively together and made many recordings. In the 1990’s-2000’s he was joined by keyboardists Malcolm Bilson and Jos van Immerseel. He continues to be a towering figure in the Baroque cello movement. Bylsma was also a co-founder of the string chamber ensemble L'Archibudelli. As a solo performer he plays regularly with such orchestras as the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Tafelmusik, Australian Chamber Orchestra, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, the Freiburger Barockorchester, and the 20th century music ensemble Rondom Kwartet. His chamber music partners include violinists Lucy van Dael and Catherine Manson, and harpsichordist Bob van Asperen. Bylsma became an Erasmus Scholar at Harvard University in 1982. He is also a noted scholar and teacher and author of Bach - The Fencing Master, a stylistic and aesthetic analysis of the first three of J.S. Bach's Cello Suites. His playing is always based on what he finds in the composers' manuscripts. However, he quickly admits that his interpretation of a work is not and should not be the only one, an idea which he also impresses on his students. Although he doesn't like to use the term 'authentic', it is in keeping with period performance that he avoids the use of steel strings. This is a major element of his tone. Both his 1695 Gofriller cello and his 1865 Pressenda are strung with gut or silver-wrapped gut. He also has a five-string 'violoncello piccolo' that he has used to record J.S. Bach's solo works. His recordings can be found on several labels, covering a variety of works, from Antonio Vivaldi to Paul Hindemith. In 1979 Bijlsma recorded the Six Suites for unaccompanied cello (BWV 1007-1012) by J.S. Bach, the first of its kind on a period instrument. He also made a second recording of the same music in 1992 on the large Servais Stradivarius and on a five-string violoncello piccolo. Many of his recordings on Sony, both as a soloist and with L'Archibudelli, have won the Edison prize, the Diapason d'or, the Liszt prize, and the Vivaldi prize. Anner Bylsma is married to Dutch violinist Vera Beths. |

BD: When you’re playing with the group, do you

play gamba?

BD: When you’re playing with the group, do you

play gamba? BD: I don’t think anyone would think that the authentic

sound is boring...

BD: I don’t think anyone would think that the authentic

sound is boring...

BD:

I often think that some of the Bruckner symphonies are like early minimalism.

BD:

I often think that some of the Bruckner symphonies are like early minimalism. AB: Sometimes it is, yes. Sometimes it’s

also that it becomes a tradition. And it’s also nice to stretch your

legs after you’ve sat through a symphony of Mahler. [Laughs]

Sometimes it is hard for us to tell because acoustics plays such a part.

When a hall is very dry, also the applause sounds very dry and short.

That plays also very much a part. When I play suites of Bach, which

I’ve done many, many times, it’s hard to see how it sounds there because

we are only half of it. I play, and you have your imagination.

When I play like a demigod and you have no imagination, you still have a

nice evening. When I play very mediocrely and you have a lot of imagination,

you still can hear a wonderful work by Bach, or a nice cello, or whatever

instrument where the fellow doesn’t play well but you still have a wonderful

evening. Mostly we meet somewhere half way — the

audience not having so much imagination and me not playing so well.

But still, it’s hard to know. Also, some halls sound wonderfully well

on stage, but are very dry in the hall. And the opposite can happen

— they sound very dry on the stage, and people say, “Don’t worry! It

sounds very good here.” It is hard working there because you don’t know

exactly how to cope with that.

AB: Sometimes it is, yes. Sometimes it’s

also that it becomes a tradition. And it’s also nice to stretch your

legs after you’ve sat through a symphony of Mahler. [Laughs]

Sometimes it is hard for us to tell because acoustics plays such a part.

When a hall is very dry, also the applause sounds very dry and short.

That plays also very much a part. When I play suites of Bach, which

I’ve done many, many times, it’s hard to see how it sounds there because

we are only half of it. I play, and you have your imagination.

When I play like a demigod and you have no imagination, you still have a

nice evening. When I play very mediocrely and you have a lot of imagination,

you still can hear a wonderful work by Bach, or a nice cello, or whatever

instrument where the fellow doesn’t play well but you still have a wonderful

evening. Mostly we meet somewhere half way — the

audience not having so much imagination and me not playing so well.

But still, it’s hard to know. Also, some halls sound wonderfully well

on stage, but are very dry in the hall. And the opposite can happen

— they sound very dry on the stage, and people say, “Don’t worry! It

sounds very good here.” It is hard working there because you don’t know

exactly how to cope with that.

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Evanston, IL, on April 18, 1989.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1994 and

1999. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.