WC: Perhaps because we had very

interesting music of our age a hundred years ago, or even seventy-five

years ago, which is less the case now. Or perhaps we have a lot

of 19th and early 20th century music — which is

pretty much what the mainstream and main line music making is all about

— pretty much everywhere in the world, and this music has

become a little bit stale. You’ve heard it too much. That’s

not to say Debussy and Brahms and the likes aren’t interesting.

They’re fabulous, but they’ve been overexposed, perhaps, and the way

they’ve been played is also, perhaps, causing a little bit of staleness

to the ear.

WC: Perhaps because we had very

interesting music of our age a hundred years ago, or even seventy-five

years ago, which is less the case now. Or perhaps we have a lot

of 19th and early 20th century music — which is

pretty much what the mainstream and main line music making is all about

— pretty much everywhere in the world, and this music has

become a little bit stale. You’ve heard it too much. That’s

not to say Debussy and Brahms and the likes aren’t interesting.

They’re fabulous, but they’ve been overexposed, perhaps, and the way

they’ve been played is also, perhaps, causing a little bit of staleness

to the ear. WC: Intelligent singers are not

difficult to find, and intelligent singers with techniques that allow

them to change priorities, from one style and from one age to another,

aren’t that difficult, either. They’re not a dime a dozen but are

by no means scarce. You can find the intelligent singer, and I’ve

been very blessed. I’ve found many intelligent singers who also

have wonderful voices and wonderful techniques.

WC: Intelligent singers are not

difficult to find, and intelligent singers with techniques that allow

them to change priorities, from one style and from one age to another,

aren’t that difficult, either. They’re not a dime a dozen but are

by no means scarce. You can find the intelligent singer, and I’ve

been very blessed. I’ve found many intelligent singers who also

have wonderful voices and wonderful techniques. WC: Students are like good wine —

there are good years and bad years in terms of natural catastrophes or

what have you. [Both laugh] You get cyclones some years and

you don’t get them, you have a run of wonderful weather and enough

rainfall to make things grow wonderfully, and other times you

don’t. I had lean years and I had very good years in terms of the

kind of student crop that I produced. Since it was a three-year

cycle, I could console myself in the sense that one of those years or

two of those years I’d have better students than the third year.

But looking over the last fifteen years of teaching, I’d say with the

ups and downs I was a very fortunate man because I was in contact with

some very, very good students, most of whom have, or still are, or have

been subsequently, members of the

Arts Florissants.

WC: Students are like good wine —

there are good years and bad years in terms of natural catastrophes or

what have you. [Both laugh] You get cyclones some years and

you don’t get them, you have a run of wonderful weather and enough

rainfall to make things grow wonderfully, and other times you

don’t. I had lean years and I had very good years in terms of the

kind of student crop that I produced. Since it was a three-year

cycle, I could console myself in the sense that one of those years or

two of those years I’d have better students than the third year.

But looking over the last fifteen years of teaching, I’d say with the

ups and downs I was a very fortunate man because I was in contact with

some very, very good students, most of whom have, or still are, or have

been subsequently, members of the

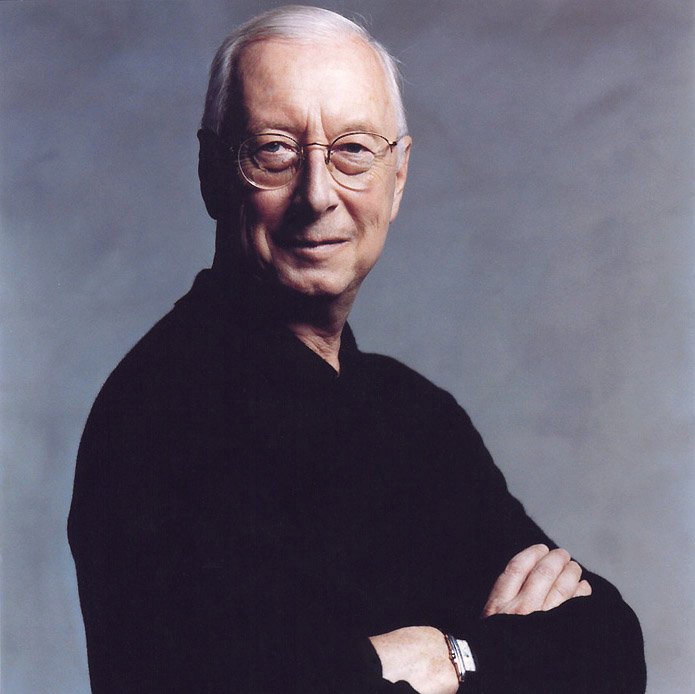

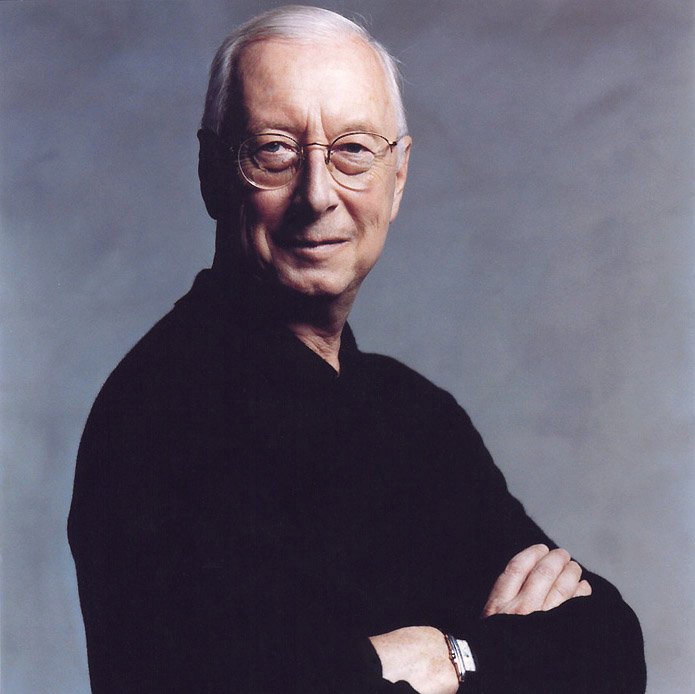

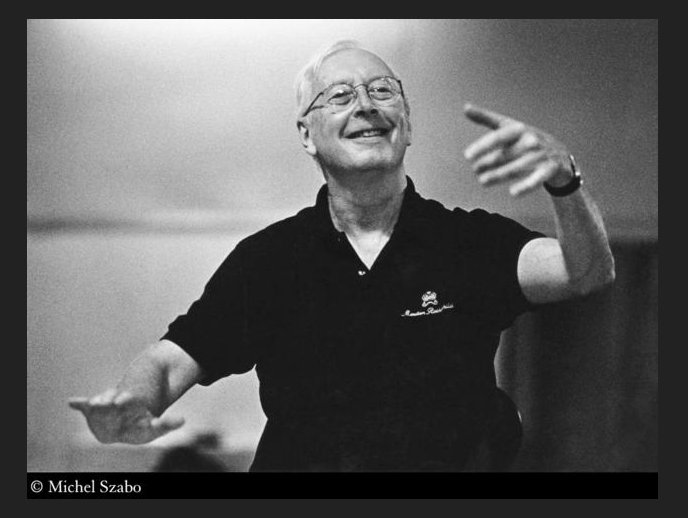

Arts Florissants.| William Christie,

harpsichordist, conductor, musicologist and teacher,

is the inspiration behind one of the most exciting musical adventures

of the last twenty-five years. His pioneering work has led to a renewed

appreciation of Baroque music in France, notably of 17th- and

18th-century French repertoire, which he has introduced to a very wide

audience. Born in Buffalo, New York, on December 19, 1944, William Christie studied at Harvard and Yale Universities, and has lived in France since 1971. The major turning point in his career came in 1979 when he founded Les Arts Florissants. As Director of this vocal and instrumental ensemble, Christie soon made his mark as a musician and man of the theatre, in both the concert hall and the opera house, with new interpretations of largely neglected or forgotten repertoire. Major public recognition came in 1987 with the production of Atys by Lully at the Opéra Comique in Paris, which then went on to tour internationally with much success. William Christie's enthusiasm for the French Baroque has never diminished. From Charpentier to Rameau, through Couperin, Mondonville, Campra or Montéclair, he is an acknowledged master of tragédie-lyrique as well as opéra-ballet, and is equally at home with French motets as with music of the court. His affection for French music does not prevent him from exploring other European repertoire, however, and he has given many acclaimed performances of works by Italian composers such as Monteverdi, Rossi and Scarlatti. He undertakes Purcell and Handel with as much pleasure as Mozart and Haydn. He has made over 70 recordings, and since 2002 has recorded exclusively for Virgin Classics, with recordings of motets by Campra and Couperin, violin sonatas by Handel, a live recording of Serse with Anne-Sofie von Otter, the release on DVD of Monteverdi's Ritorno d'Ulisse in patria as performed in Aix-en-Provence, Charpentier's Te Deum and Judicium Salomonis, followed, more recently by the release Purcell's Divine Hymns and Haydn's Creation. Much in demand as a guest conductor, William Christie receives regular invitations from prestigious opera festivals such as Glyndebourne, where he has conducted the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in productions of Theodora and Rodelinda by Handel (the latter was revived at the Théâtre du Châtelet in January 2002). Other guest appearances include Zurich Opera, where he has conducted Iphigénie en Tauride by Gluck, Les Indes galantes by Rameau, and Radamisto and Orlando by Handel, and the Opéra national de Lyon where, following Così fan tutte in 2005, he will conduct The Marriage of Figaro in June 2007. Since 2002, he has appeared regularly as a guest conductor with the Berlin Philharmonic. William Christie is equally committed to the training and professional development of young artists, and he has nurtured several generations of singers and instrumentalists over the last twenty-five years. Indeed, many of the music directors of today's Baroque ensembles began their careers with Les Arts Florissants. Between 1982 and 1995, Christie was a Professor at the Paris Conservatoire, with responsibility for the early music class. He is often invited to give master classes, or to lead academies such as those at Aix-en-Provence and Ambronay. Wishing to develop further his work as a teacher, he created an academy for young singers in Caen, called Le Jardin des Voix, whose first two sessions, in 2002 and 2005, generated a huge amount of interest in France and elsewhere in Europe as well as in the United States. William Christie acquired French nationality in 1995. He is an Officier dans l'Ordre de la Légion d'Honneur as well as Officier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. |

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Evanston, IL, on

November 20, 1995. Portions

(along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1996 and 1999. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.