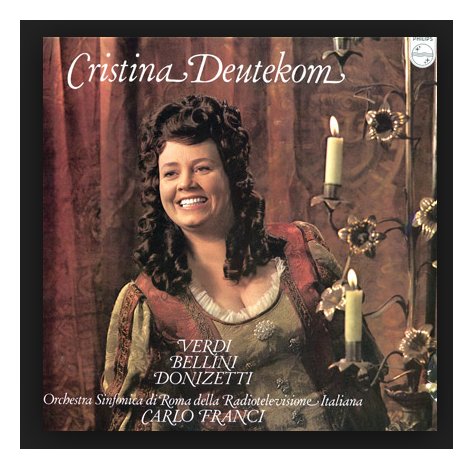

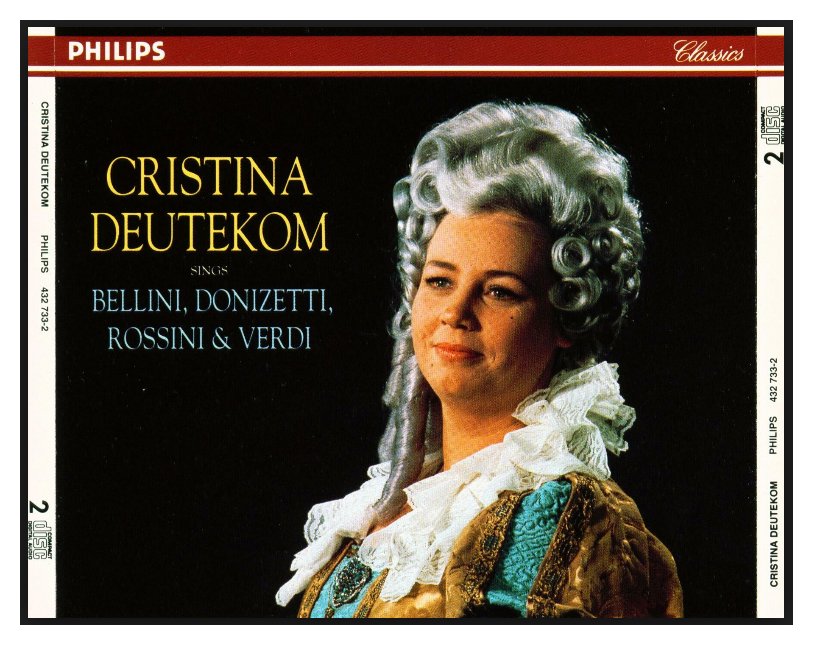

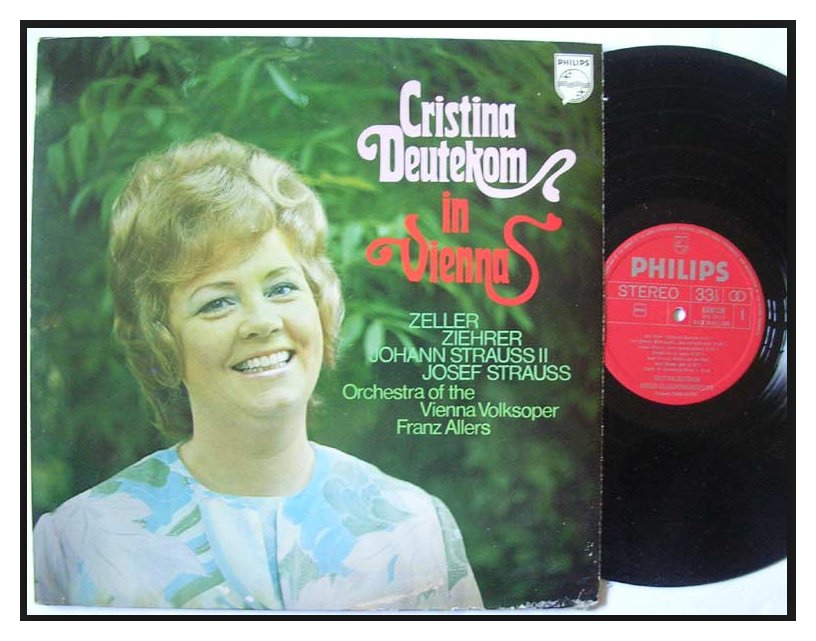

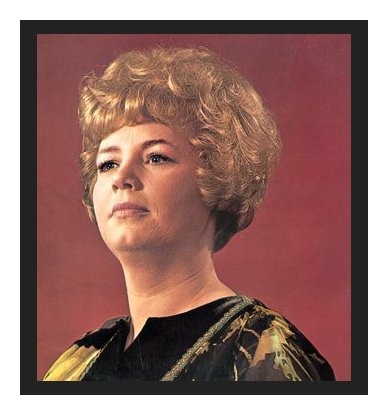

Deutekom made a relatively late debut in 1963 at thirty-two, in Amsterdam, as the Queen of the Night. Hers was no soubrette voice but a dramatic instrument, despite its extension up to the high F and beyond; proper preparation took extra time and patience. Once onstage, however, she was in demand in every opera house in the world for her extraordinary Queen, whose combined power, accuracy, and brilliance exceeded any in living memory. She recorded the role for Decca under Solti in I969, and later made a film of it with the Hamburg State Opera. "The bright, deadly accurate staccatos glitter and peck: a predatory night-bird with a curiously sinister suggestion of clockwork" J. B. Steane wrote of her in The Grand Tradition. "It is the Queen of Night one has always wanted to hear." Other prodigious achievements notwithstanding, it is for her Queen that Deutekom has entered the operatic pantheon. She also sang other Mozart roles (Donna Anna, Fiordiligi, Konstanze, Vitellia), and her very first commercial recording, featuring arias from Enführung, Don Giovanni, and Zauberflöte, won the Grand Prix du Disque. The bel canto repertory and the early operas of Verdi also showed her full artistic expression. There is a paucity of great Dutch singers in history (besides Deutekom, only Gre Brouwenstijn gained international acceptance in opera in the last half century), but Deutekom overcame the disadvantage of a sound neither Italianate nor naturally warm by singing with exceptional warmth of feeling and authenticity of style. This and her capacity for bravura allowed her to reveal to late-twentieth-century audiences the vocal essence of certain early-nineteenth-century works with a freedom, security, and panache. Reviewing her Lombardi with the San Diego Opera, Martin Bernheimer wrote in I979 that "Cristina Deutekom is a dramatic coloratura - the real, rare thing. She may sound a bit strident on occasion, but the power, the flexibility, the stamina, and, yes, the finesse of her singing as Giselda mark her as a soprano with relatively few contemporary - or historical - peers." The last years of Deutekom’s career were compromised by the effects of major illness, culminating in emergency open-heart surgery. She resumed singing rather soon following this trauma but found that, although the voice itself was not impaired, the requisite energy and stamina for a great role were no longer hers. Her final appearance in the United States was on November 2, 1986 as Bellini’s Norma, one of her most frequent roles, at San Diego, scene of a number of previous personal successes. Shortly thereafter she took leave of the stage altogether at an unscheduled farewell at Bilbao, in the title role of Jesús Guridi’s powerful 1920 lyric drama Amaya, sung in the original Basque. In retirement in Amsterdam, she takes more joy in teaching than do the vast majority of former divas, and she has maintained her own vocal health to the greatest extent possible. In 1990 she re-entered the recording studio, making Christmas with Cristina Deutekom, and she surprised everyone by singing in public in August 1996 (coincidentally the month of her sixty-fifth birthday). The occasion was an Amsterdam gala performance during which she performed the Bolero from I vespri siciliani and a Viennese operetta aria. The Dutch audience, aware that she had survived a second emergency heart operation (in 1994), rose in acclaim after each selection. In January I997 she ventured to commit to disc the principal scenes of Donizetti’s three English queens (the heroines of Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda, and Roberto Devereux), roles that had not been part of her large stage repertory. |

BD: Is there enough in the character to make it

more than just a concert?

BD: Is there enough in the character to make it

more than just a concert? BD: So you separate yourself from it?

BD: So you separate yourself from it? BD: Are you pleased with the recordings you have

made?

BD: Are you pleased with the recordings you have

made? BD: You are more of a firebrand in real life?

BD: You are more of a firebrand in real life? CD: Yes!

CD: Yes! CD: After this I go call to Bilbao, and then back

to Holland to do Semiramide.

CD: After this I go call to Bilbao, and then back

to Holland to do Semiramide.© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone (she was in San Diego, I was in Chicago) on October 15, 1986. Because the sound of the tape was so poor, instead of playing portions on the air, I related quotations from the interview during a broadcast on WNIB the following year, along with commercial recordings. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.