|

On his official website are two biographies, both of which are reproduced here. The first is called 'Professional Bio', and the second is listed as 'A Personal Bio'.

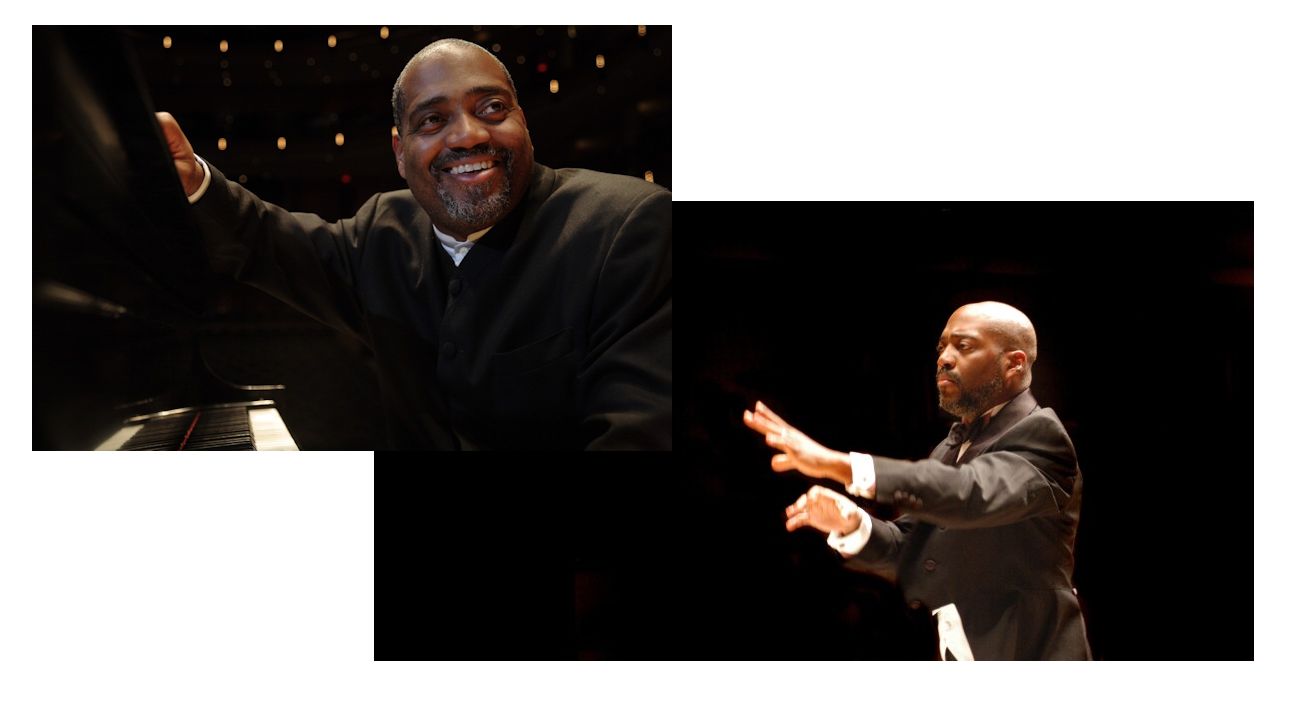

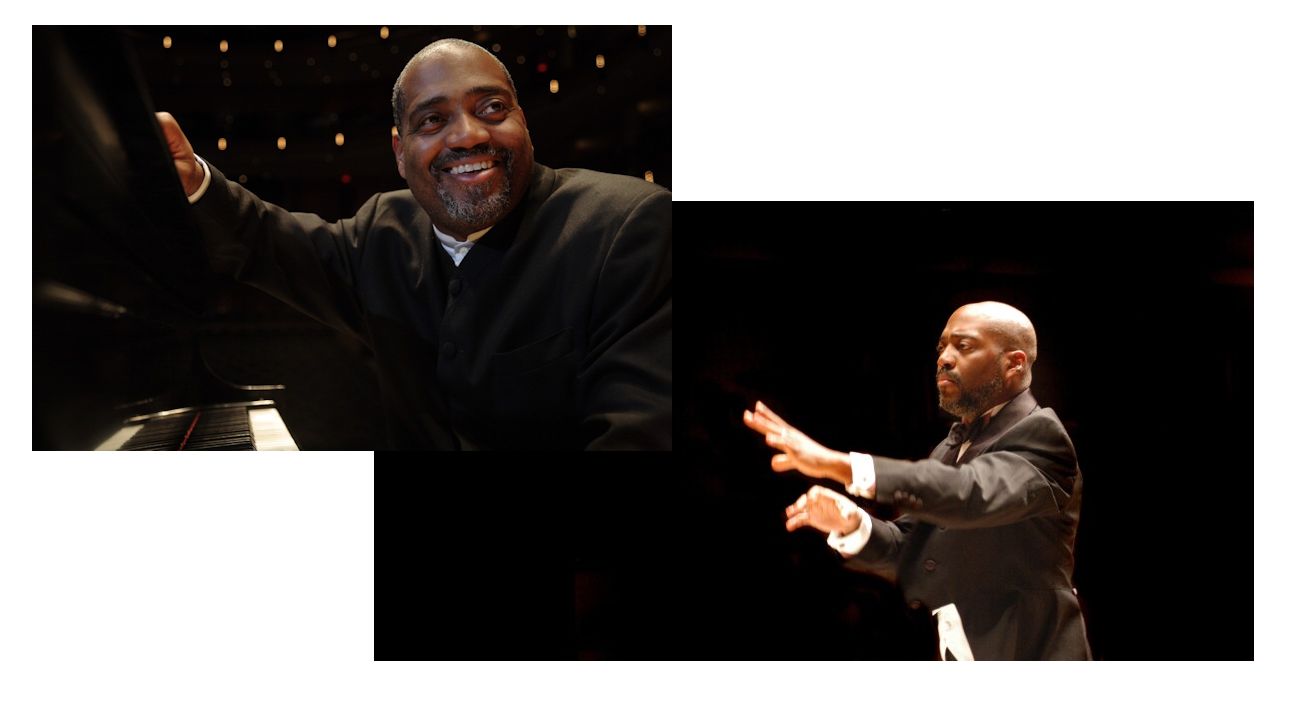

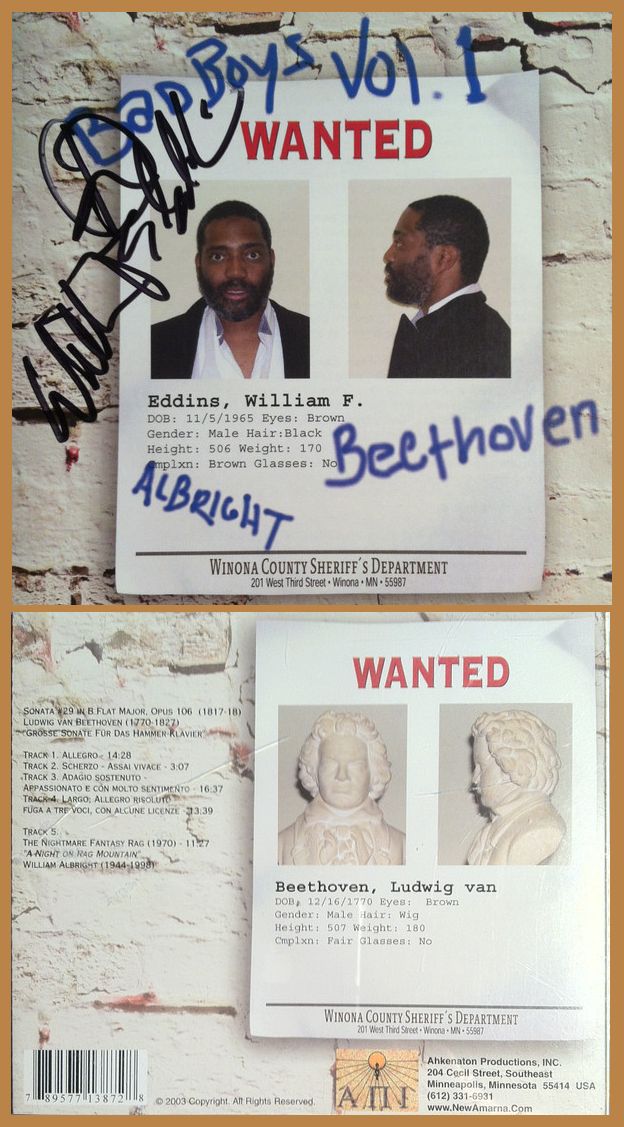

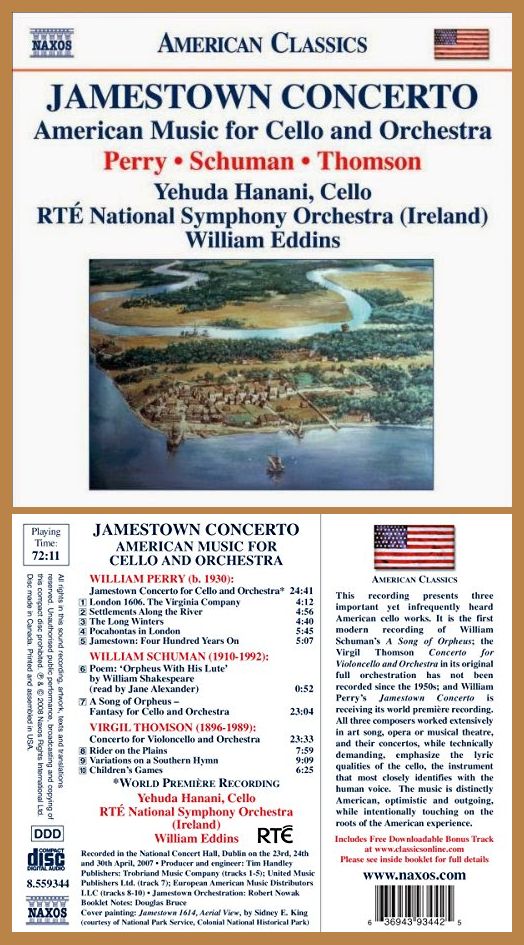

Engagements have included the New York Philharmonic, St. Louis Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, the symphony orchestras of San Francisco, Boston Minnesota, Cincinnati, Atlanta, Detroit, Dallas, Baltimore, Indianapolis, Milwaukee, Houston, as well as the Los Angeles and Buffalo Philharmonics. Internationally, Eddins was Principal Guest Conductor of the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra (Ireland). He has also has conducted the Berlin Staatskapelle, Berlin Radio Orchestra, Welsh National Opera, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Bergen Philharmonic, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, Barcelona Symphony Orchestra, and the Lisbon Metropolitan Orchestra. Career highlights include taking the Edmonton Symphony Orchestras to Carnegie Hall in May of 2012, conducting RAI Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale on Italian television, and leading the Natal Philharmonic on tour in South Africa with soprano Renée Fleming. Equally at home with opera, he conducted a full production of Porgy and Bess with Opera de Lyon both in France and the Edinburgh Festival and a revival of the production during the summer of 2010. Mr. Eddins is an accomplished pianist and chamber musician. He regularly conducts from the piano in works by Mozart, Beethoven, Gershwin and Ravel. He has released a compact disc recording on his own label that includes Beethoven’s Hammer-Klavier Sonata and William Albright’s The Nightmare Fantasy Rag. Mr. Eddins has performed at the Ravinia Festival with both the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Ravinia Festival Orchestra. He has also conducted the orchestras of the Aspen Music Festival, the Hollywood Bowl, Chautauqua Festival, the Boston University Tanglewood Institute and the Civic Orchestra of Chicago. A native of Buffalo, NY, Mr. Eddins attended the Eastman School of Music, studying with David Effron and graduating at age eighteen. He also studied conducting with Daniel Lewis at the University of Southern California and was a founding member of the New World Symphony in Miami, FL. * * *

* *

William Eddins is a husband, father, Taoist, musician, writer, and entrepreneur living and working in the great city of Minneapolis. He has been married to Jennifer Gerth, Principal Clarinet of the Duluth Superior Symphony Orchestra, for twenty years, and they have raised two young men who are musicians and athletes. Bill is the Music Director Emeritus of the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, and has also served as Principal Guest Conductor of the National Symphonie of Ireland, Resident Conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and Associate Conductor of the Minnesota Orchestra. Bill is co-founder of MetroNOME Brewery LLC, a socially missioned brewery established in the wake of the public unrest during the summer of 2020 with the objective of Nurturing Outstanding Music Education in the Twin Cities Metro. Proceeds from MetroNOME will go to providing musical instruments, lessons, and education for underprivileged youth in the Twin Cities Metro area. Bill strongly believes that education in general, and music education in particular, is the gateway to a better, more fulfilling life, and he wants to ensure that any child who loves music should be able to find a way to play. Bill is the author of The Shadows of Venice, a historical fiction trilogy set in Venice (Italy) during November, 2013. The Shadows of Venice brings together Bill’s love of music, history, fantasy/fiction, food, and the city of Venice, and is due out in late 2021. A portion of the proceeds from the sale of The Shadows of Venice will go to supporting music education in the Twin Cities Metro. Bill has an active and liberal life outside the music world.

He is a certified Thai Yoga Massage practitioner who specializes in helping

performing artists and athletes, an umpire for the United States Tennis

Association, and is in an apprenticeship to become a concert piano technician.

His many hobbies include road cycling, cooking, home brewing, and learning.

Bill hopes that the music he makes brings you joy. |

© 2001 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 17, 2001. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.