[Items from two newspapers about this

Liszt discovery.]

150-Year Wait For a Lost Liszt

Two-continent debut will feature

1839 piano concerto.

By Laura Van Tuyl, Staff writer of The

Christian Science Monitor / May 3, 1990

BOSTON

Audience members will be on the edge of their seats when a piano concerto

by Franz Liszt receives its world premiere tonight in Chicago's Orchestra

Hall. Performance of the "new" work has been eagerly awaited by music enthusiasts

and Liszt historians, ever since 1988, when a doctoral student from the University

of Chicago announced he had stumbled upon missing manuscripts while doing

research in Europe.

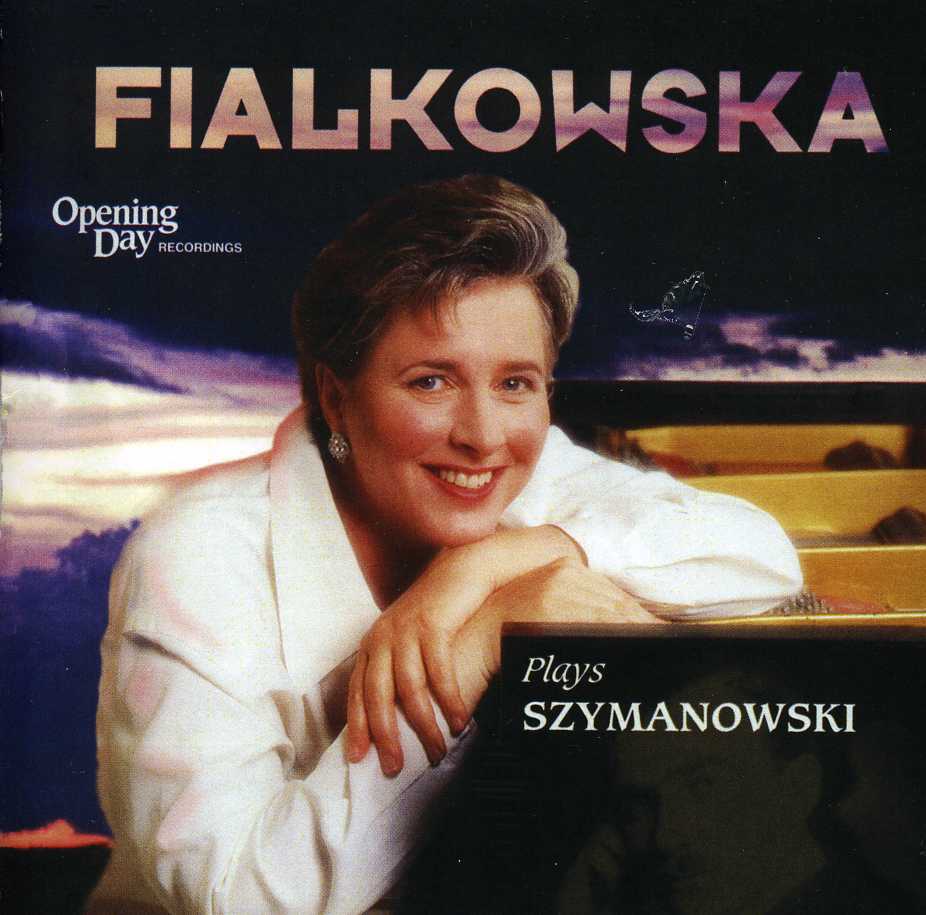

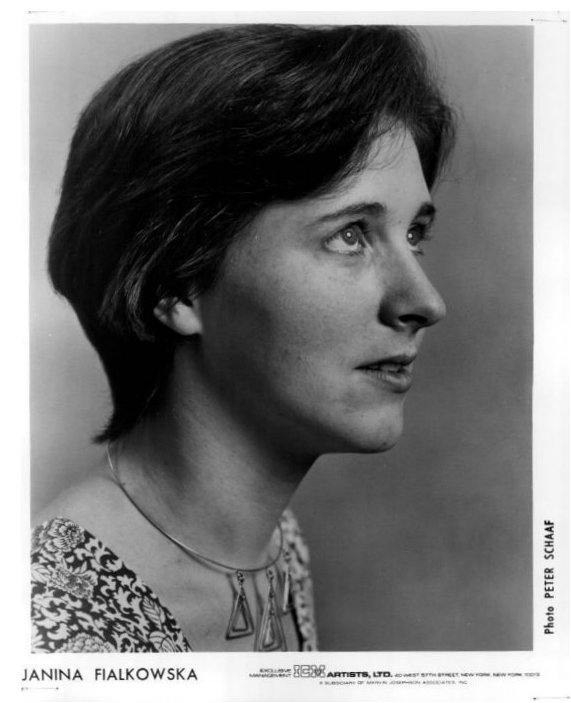

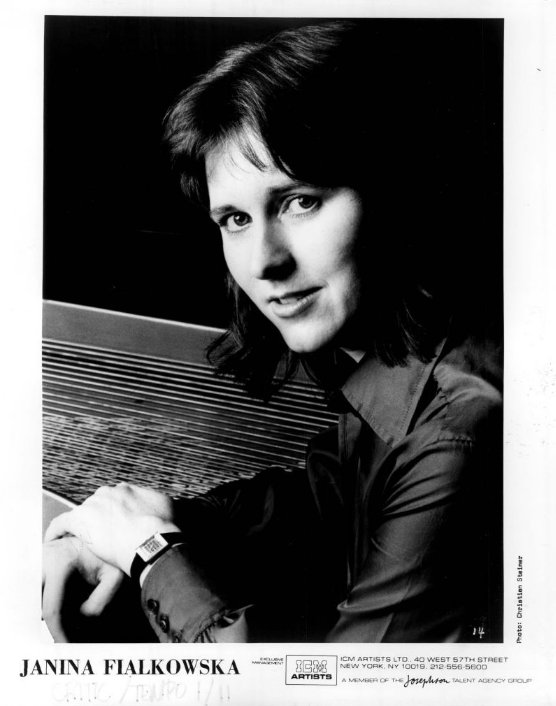

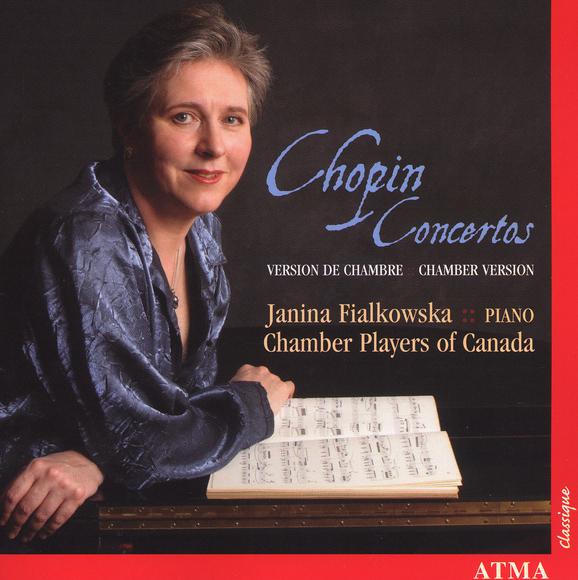

``It's a huge find,'' says pianist Janina Fialkowska, reached by phone, who

will play the work with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under the direction

of associate conductor Kenneth Jean. Ms. Fialkowska ranks the piece as a

major piano work, sure to excite the classical musical world.

The European debut of the piece is tomorrow in The Hague, Netherlands, where

Stephen Mayer performs with the Resedentie Orkester at The Hague Museum.

The concerto, similar in form to the composer's other two, appears to date

from 1839. "At that time, we think of [Liszt] as a virtuoso pianist who was

stunning audiences around Europe," said Jay Rosenblatt, discoverer and editor

of the work, in a phone interview. "This is a good opportunity for the general

public to realize Liszt was always concerned with the serious side of composing."

The 15-minute work, written in one continuous movement, includes cadenza

passages for the soloist at the beginning, "a lovely second theme, which

is really quite beautiful," says Fialkowska, and a "marvelously virtuosic"

ending, she adds.

When Rosenblatt went to Europe to research Liszt's works for piano and orchestra,

he had no idea he would unearth a lost concerto. From archival materials,

he was able to piece together a hitherto unknown composition, which had become

dispersed over three countries. Some pages had been wrongly identified as

drafts of Concerto No. 1 and shuffled into piles of unrelated manuscripts.

Liszt had scratched out a few passages of the solo part, "and there is no

question he intended to come back and revise it," Rosenblatt says. But the

original notes are still legible under the cross-hatch, making a performance

of the work possible. "It's an example of where his development was at the

time he wrote it."

Fialkowska says the premiere "gives me an amazing sense of power" because

there is no precedent for how the concerto should be played. "There are no

dynamics markings, no tempo indications - just the bare notes."

Subsequent performances are slated for Chicago (May 5 and 8); Santa Barbara,

Calif., by the Festival Orchestra of the Music Academy of the West (Aug.

5); New York, by the New York Philharmonic (Jan. 3-5, 1991); and Youngstown,

Ohio, by the Youngstown Symphony (Jan. 12, 1991).

- - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

May 26, 1991|By Steven Brown, Orlando Sentinel

Classical Music Critic

(...) This week, the main item of interest is a recently discovered, 15-minute

piano concerto by Liszt, which Orlando audiences will finally have a chance

to hear.

Jay Rosenblatt, a doctoral student at the University of Chicago, unearthed

the concerto in Europe about four years ago. Last spring, pianist Fialkowska

and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra gave the concerto its world premiere with

Jean, who also serves as the Chicago Symphony's associate conductor, on the

podium.

Rosenblatt was looking through manuscripts in an archive in Weimar, then

part of East Germany, when he came across the first traces of the new concerto

late in 1987. At the time, he was studying the well-known Piano Concerto

No. 1.

''What I discovered among the material for the First Piano Concerto was this

material for another work in the same key, which had been labeled by the

archive as part of the First Concerto,'' Rosenblatt said. ''But upon closer

examination, I was convinced that it was a completely separate one-movement

work that happened to share the same key.

''But I didn't have the composer's own manuscript - what I had to work with

was a copyist's manuscript. Liszt had probably given the concerto to an associate

to make a clean copy of it, and this copy had a lot of mistakes. Liszt had

not gone back to check it.''

During the next spring, Rosenblatt found Liszt's original. He was in Budapest,

and once again he made his discovery amid papers related to the First Concerto.

Three pages of the new concerto were missing - but thanks to the copyist's

version he already had, Rosenblatt was able to fill in what was lost.

The music Orlando hears (now dubbed the Piano Concerto in E-Flat Major, Opus

Posthumous) will be ''99 percent Liszt,'' Rosenblatt said. His main contribution

lay in recognizing that the manuscripts he found belonged to an independent,

previously lost piece. Otherwise, Rosenblatt explained, what editing the

concerto needed mainly involved correcting some wrong notes and finishing

some lines in the orchestral parts that obviously had been inadvertently

broken off.

Liszt wrote the piece in the late 1830s, Rosenblatt said, when he was under

30 years old. But there's no evidence that he ever played it in public. If

he had, Liszt probably would have thinned out the piano part - which is packed

with notes, making it awkward and all the more demanding for the soloist.

But even as it stands, Rosenblatt added, the concerto is unmistakably Lisztian

- in its fireworks and in its free-flowing, one-movement form.

''There's no question that this is Liszt's music,'' Rosenblatt said. ''It

bears all the fingerprints of the great master.''

|

JF

JF JF

JF JF

JF JF

JF BD

BD