RF:

Well yes and no, because Smetana was

very strongly influenced by Wagner and by

others. Dvořák started to write

opera early, but his major operas came rather late in his life.

He was much more in the line of Brahms and the

Viennese School; he was also writing more symphonies and

string quartets. But there is one

similarity: both of these composers were trying to write

operas which would be for the Czech audience, because up to this time

there was no Czech opera. Opera was only

German, you know, the modern operas. There was practically no

operatic literature in Bohemia, so when Smetana came

back from his stay in Sweden, he became conductor

of the National Theater — for a very short time

because he soon became deaf — and decided that

something had to be done to

provide the people with repertory. And of course, he wanted to

take something which was very accessible to the general Czech audience,

such as Bartered Bride with

its village scenes, Dalibor,

which is kind of

mythological, Libuše, which

was one of the mythological

princesses, and things that were really more in the folk

vein. And Dvořák did more of less

the same, you know. Dvořák also

started to write in this way, with very simple librettos and very

simple stories, but the kind of music which was very easy to

understand, and which became quite popular in a

short time. His great opera is Rusalka,

one of his last operas, which became his Bartered Bride, the most

popular opera in Czechoslovakia. I saw it when I was four

years old! [Laughs] This

opera never, never crossed the border. Of course it was very

popular in Czechoslovakia, but it never really came to the

international stage, with the exception of Vienna. In America

there was only one production, in Charleston for the Spoleto Festival,

and the Juilliard School gave it once. So when it was just done

in

Seattle, this was really the first big performance on

this continent, and I’m happy to say, a very fine

success. So I hope it travels more now!

RF:

Well yes and no, because Smetana was

very strongly influenced by Wagner and by

others. Dvořák started to write

opera early, but his major operas came rather late in his life.

He was much more in the line of Brahms and the

Viennese School; he was also writing more symphonies and

string quartets. But there is one

similarity: both of these composers were trying to write

operas which would be for the Czech audience, because up to this time

there was no Czech opera. Opera was only

German, you know, the modern operas. There was practically no

operatic literature in Bohemia, so when Smetana came

back from his stay in Sweden, he became conductor

of the National Theater — for a very short time

because he soon became deaf — and decided that

something had to be done to

provide the people with repertory. And of course, he wanted to

take something which was very accessible to the general Czech audience,

such as Bartered Bride with

its village scenes, Dalibor,

which is kind of

mythological, Libuše, which

was one of the mythological

princesses, and things that were really more in the folk

vein. And Dvořák did more of less

the same, you know. Dvořák also

started to write in this way, with very simple librettos and very

simple stories, but the kind of music which was very easy to

understand, and which became quite popular in a

short time. His great opera is Rusalka,

one of his last operas, which became his Bartered Bride, the most

popular opera in Czechoslovakia. I saw it when I was four

years old! [Laughs] This

opera never, never crossed the border. Of course it was very

popular in Czechoslovakia, but it never really came to the

international stage, with the exception of Vienna. In America

there was only one production, in Charleston for the Spoleto Festival,

and the Juilliard School gave it once. So when it was just done

in

Seattle, this was really the first big performance on

this continent, and I’m happy to say, a very fine

success. So I hope it travels more now!  BD:

Do you

feel that you are the keeper of the flame of Janáček?

BD:

Do you

feel that you are the keeper of the flame of Janáček? BD: I see! Now

the

other modern Czech composer is Martinů.

BD: I see! Now

the

other modern Czech composer is Martinů. BD:

Well, from the huge repertoire of

piano music, either concertos or solo literature, how do you decide

— beyond the Czech literature — which

pieces you will study and spend

time on, and which you will let go?

BD:

Well, from the huge repertoire of

piano music, either concertos or solo literature, how do you decide

— beyond the Czech literature — which

pieces you will study and spend

time on, and which you will let go? RF:

There are many wonderful pianists and they are

all very good. I think they just have to try to find

themselves, in a way, because at the beginning

they are going in certain directions. Especially

nowadays when there are so many competitions, that gives you some

kind of ideas which they want to do. But later they start touring

and they start to develop their own personality, and I

think it’s important. I think a personality is important because

that is what makes the music really alive. Someone is coming who

is playing the notes — which are always the same

— but nevertheless it’s different if you hear it from A or

from B. It’s really the question of touch and of the sound and of

general conceptions. That’s what makes the music alive, otherwise

it would be a dead thing. The same

goes for recording. You can hear the most wonderful recording

— and there are wonderful recordings — but

after a while

it’s always the same. It’s great, but you know

this is it. When you go to the concert, it’s then a performance

which may be not so great as the recording, but it lives. It’s

there and somehow you hear that it’s created right on

the spot on the spur of the moment.

RF:

There are many wonderful pianists and they are

all very good. I think they just have to try to find

themselves, in a way, because at the beginning

they are going in certain directions. Especially

nowadays when there are so many competitions, that gives you some

kind of ideas which they want to do. But later they start touring

and they start to develop their own personality, and I

think it’s important. I think a personality is important because

that is what makes the music really alive. Someone is coming who

is playing the notes — which are always the same

— but nevertheless it’s different if you hear it from A or

from B. It’s really the question of touch and of the sound and of

general conceptions. That’s what makes the music alive, otherwise

it would be a dead thing. The same

goes for recording. You can hear the most wonderful recording

— and there are wonderful recordings — but

after a while

it’s always the same. It’s great, but you know

this is it. When you go to the concert, it’s then a performance

which may be not so great as the recording, but it lives. It’s

there and somehow you hear that it’s created right on

the spot on the spur of the moment. RF:

Ah, that’s the greatest problem for the pianist

because each pianist is different, as is each piano. No

matter how good it is, it’s still a different piano, no matter

what. Sometimes it doesn’t take long and you

have the feeling that you are in harmony with the piano; sometimes you

just have to fight it and you never feel that you are a

hundred percent master of it. On the other hand, again, there

is a little compensation because each piano is a little different, so

it also forces you to see a little bit differently and to

try the possibilities of the

instrument. So it has two sides. But nowadays, most of the

pianos are pretty good. In the

older days it was a different story. Sometimes I played a

horrible piano, and then of course you can’t do anything. But

now it’s very, very good. Occasionally you still find a bad

piano. [Laughs] And of course, the other important thing is

the acoustics of the hall; the same piano can sound different

in one hall than the other hall. In one hall it is wonderful and

in the other hall it doesn’t sound at all. It’s very important to

know about things other than the instrument, meaning the acoustic

conditions and

all this.

RF:

Ah, that’s the greatest problem for the pianist

because each pianist is different, as is each piano. No

matter how good it is, it’s still a different piano, no matter

what. Sometimes it doesn’t take long and you

have the feeling that you are in harmony with the piano; sometimes you

just have to fight it and you never feel that you are a

hundred percent master of it. On the other hand, again, there

is a little compensation because each piano is a little different, so

it also forces you to see a little bit differently and to

try the possibilities of the

instrument. So it has two sides. But nowadays, most of the

pianos are pretty good. In the

older days it was a different story. Sometimes I played a

horrible piano, and then of course you can’t do anything. But

now it’s very, very good. Occasionally you still find a bad

piano. [Laughs] And of course, the other important thing is

the acoustics of the hall; the same piano can sound different

in one hall than the other hall. In one hall it is wonderful and

in the other hall it doesn’t sound at all. It’s very important to

know about things other than the instrument, meaning the acoustic

conditions and

all this. RF:

No, it is the same. Of course in chamber

music you have to try to

balance the sound with the other instruments. With the orchestra,

usually there’s always the so-called leading actor of the

drama. The orchestra usually is trying to go a little

bit down, to give the soloist the possibility to come through.

When you play alone, you can afford to do things which maybe you

couldn’t do with the orchestra; certain pianissimos, certain

nuances which you can’t do in the orchestra. You have to be a

little bit careful, because after all, playing with the orchestra is

like playing chamber music. I speak of the great

concertos like Brahms and Mozart and Beethoven. It’s not just

accompaniment; it goes all together. The orchestra is as

important as the solo

instrument, so you have to take it into consideration and when

it’s necessary, you have to go in the background to give the orchestra

the lead. At other points, the orchestra goes in the background

when

the soloist has the lead. So it’s a kind of give and take.

And the conductor is very important because he

is the one who is trying to find the right balance between

instruments. He has to follow the soloist and he has

to hold the orchestra together. So the conductor is very

important.

RF:

No, it is the same. Of course in chamber

music you have to try to

balance the sound with the other instruments. With the orchestra,

usually there’s always the so-called leading actor of the

drama. The orchestra usually is trying to go a little

bit down, to give the soloist the possibility to come through.

When you play alone, you can afford to do things which maybe you

couldn’t do with the orchestra; certain pianissimos, certain

nuances which you can’t do in the orchestra. You have to be a

little bit careful, because after all, playing with the orchestra is

like playing chamber music. I speak of the great

concertos like Brahms and Mozart and Beethoven. It’s not just

accompaniment; it goes all together. The orchestra is as

important as the solo

instrument, so you have to take it into consideration and when

it’s necessary, you have to go in the background to give the orchestra

the lead. At other points, the orchestra goes in the background

when

the soloist has the lead. So it’s a kind of give and take.

And the conductor is very important because he

is the one who is trying to find the right balance between

instruments. He has to follow the soloist and he has

to hold the orchestra together. So the conductor is very

important. RF: It’s a great

orchestra, really a great

orchestra, Chicago. Wonderful orchestra. You know, I

played with them a long time ago, in 1941 at Ravinia with Thomas

Beecham. That was the first time I played

here. It was sort of a distant orchestra, but now it

became super. I think Barenboim is a good man for the

position. I think

it was a good choice.

RF: It’s a great

orchestra, really a great

orchestra, Chicago. Wonderful orchestra. You know, I

played with them a long time ago, in 1941 at Ravinia with Thomas

Beecham. That was the first time I played

here. It was sort of a distant orchestra, but now it

became super. I think Barenboim is a good man for the

position. I think

it was a good choice. BD:

[Surprised] Oh, really? I don’t think I’ve

heard them with piano.

BD:

[Surprised] Oh, really? I don’t think I’ve

heard them with piano.|

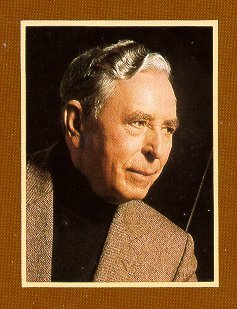

Rudolf Firkusny, an Elegant and Patrician Pianist, Is Dead at 82

The cause was cancer, said his press agent, Constance Shuman. During

a long career, Mr. Firkusny was a favorite of audiences, piano

connoisseurs and Czech-music specialists alike. He achieved still wider

recognition in his late years in unexpected ways. In 1990, at 78, he

appeared on a basketball court in concert dress, as a foil to David

Robinson of the San Antonio Spurs in a popular television commercial

for Nike sneakers. "Music needs all kinds of encouragement," Mr.

Firkusny said at the time. Honored in His Homeland Shortly afterward, he made a triumphant return to Czechoslovakia, as the country was then still called. Although he had not performed there for 44 years because of his staunch opposition to Communist control, he was recognized for his lifelong contributions to Czech music and was awarded an honorary doctorate from Charles University in Prague. He said in an address on that occasion that a musical interpreter, like a philosopher, is engaged in an eternal search for the meaning of human existence. "If, throughout my life, I had not been asking myself exactly those questions over the scores," he added, "I would feel today that my life has been wasted by piano playing which was basically useless." He was greeted on that visit by President Vaclav Havel. Mr. Firkusny's visibility grew in recent years even without particular action on his part. Although he was always a versatile artist and became especially involved with Mozart and Beethoven, his great specialty was the music of his compatriots, Dvorak, Smetana, Janacek and Martinu. Long condescended to as quaint nationalists, these composers have come into their own of late, and Mr. Firkusny's contribution has finally been recognized at its full value. He played a major hand in the 1993 Bard Music Festival in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., which centered on Dvorak. He gave a Janacek recital in the composer's hometown of Brno in October. His last performance was a recital in January in Covington, Ga. Mr. Firkusny was born on Feb. 11, 1912, in Napajedla, Moravia. For 10 years, from the age of 5, he studied with Leos Janacek. "It was not piano but music that I studied with him," he said. "I composed also. It was a great experience." He went on to study piano with Vilem Kurz and composition with Josef Suk, Dvorak's son-in-law, at the Prague Academy of Music. He pursued piano studies abroad, traveling to France to work with Alfred Cortot and to Germany and Italy to work with Artur Schnabel. "You do not need a teacher anymore, only the public," Cortot told him after conducting a Paris concert in which Mr. Firkusny was the soloist. Imprudently billed as "the greatest pianist Czechoslovakia has ever produced," Mr. Firkusny made his American debut in 1938, at Town Hall in New York. In a review in The New York Times, Noel Straus remained skeptical beneath faint praise: "It seemed difficult to believe that his interpretative gifts, meager as they proved, or even his technical abilities, were superior to those of Dussek, Moscheles, Dreyschock or Stradal, to mention the first Czech pianists who come to mind." But three years later in Town Hall,

Straus found a "gain on the interpretive side as well as in technical

virtuosity," which helped place Mr. Firkusny "well to the front among

the younger pianists of the day." Subsequent New York reviews were

remarkable, almost tedious, in their uniformity of praise for Mr.

Firkusny's artistry. "Rudolf Firkusny comes with a guaranteed-to-please

label, money back if not satisfied," Harold C. Schonberg summed up once

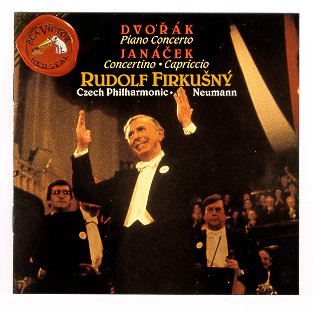

and for all in 1971 in The Times. Became American Citizen Mr. Firkusny settled in New York in 1940, after the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. With the Communist takeover in 1948, he abandoned plans to return to his homeland and became an American citizen. A fierce advocate of democracy, he returned to Czechoslovakia only to visit family and friends. He and his wife, Tatiana, were married there in 1960, and he maintained close ties with the family of the nation's first president, Tomas Masaryk. In making music, Mr. Firkusny once said: "I have never considered myself the most important man. That is the composer." He gave up serious composition early but continued to cultivate relationships with composers, American as well as Czech, throughout his career. He formed a special friendship with Bohuslav Martinu, and brought several of his works to life. He played Martinu's Second Piano Concerto on his return to Prague in 1990. Mr. Firkusny performed all over the United States as well as in Europe and Japan. He was a frequent soloist with the New York Philharmonic and other major American orchestras and a favorite collaborator of George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra. He was a regular fixture at the Mostly Mozart festival and in other series in New York and a valued chamber musician. He taught at the Juilliard School. He made many excellent recordings, notably his third version of the Dvorak Piano Concerto, with Vaclav Neumann and the Czech Philharmonic; a superb disk of Janacek solo works, and a collection of Czech songs with Gabriela Benackova, all on RCA Victor. Awaiting release from RCA are Martinu's Second, Third and Fourth Piano Concertos. "If I want to play, I have to play damn well, otherwise I might as well close up shop," the perennially self-effacing pianist said two decades ago. He continued to please audiences and critics at least through the Bard Festival last year and closed up shop only in recent months, when he was physically unable to carry on. In addition to his wife, he is survived by a daughter, Veronique Callegari of Manhattan; a son, Igor, of Boston, and two grandchildren. |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on November 2,

1990. Portions (along with recordings) were

broadcast on WNIB the following year and in 1992, 1994 and 1997.

The

transcription was made and posted on this website early in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award-winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.