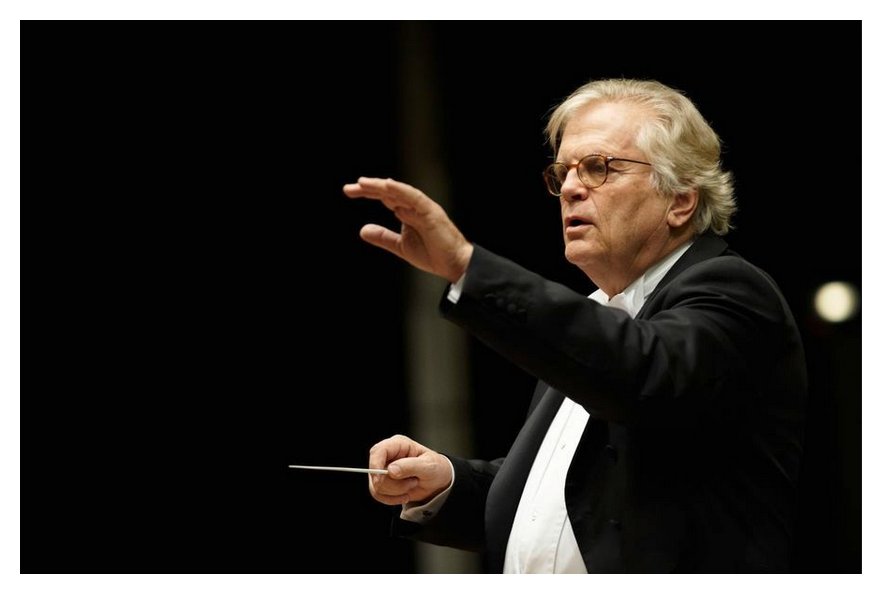

Pianist / Conductor Justus Frantz

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Justus Frantz is an internationally acclaimed German pianist and conductor.

He began playing piano at the age of four. Professor Eliza Hansen early recognized

his talent fostered it. Later the young musician studied conducting under

Wilhelm Kempff.

At age of 23, Frantz became the youngest musician ever to be granted a scholarship

by the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes (German National Scholarship

Foundation). In 1967 he won a prize at an international music competition

held by a famous German TV channel, which marked the beginning of his international

fame.

In 1970, he rose into the group of first-class pianists with the Berlin Philharmonic

Orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan. He celebrated his US debut five

years later with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Leonard

Bernstein, whose musical ideals he continues to adhere to. Bernstein's dream

of an international, young and professional orchestra inspired Frantz to

found the Philharmonia of the Nations in 1995. As the chief conductor, Frantz

works throughout the world with the constantly updating cast of the orchestra,

also discovering new names. He does a lot to cultivate young talents, and

therefore his schedule includes frequent auditions, which gives young musicians

a great chance to start an international career. Among the musicians who

were first introduced to the audience by Justus Frantz are violinists Maxim

Vengerov, Midori and Joseph Lendvay, pianist Evgeny Kissin, and composer

Martin Panteleev.

In 1986 Justus Frantz founded the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival and was

its director for nine years turning it into one of the world's greatest music

forums.

Justus Frantz has been awarded several television prizes of high prestige

for the highly successful TV programs that he has produced including the

famous Achtung! Klassik ("Attention! Classical music").

Since 1989, Frantz has been a special ambassador for the UN High Commission

for Refugees and in the same year he received the German equivalent to the

OBE, the Grosse Bundesverdienstkreuz.

Frantz is the chief conductor of the Philharmonia of the Nations and works

on a regular basis with renowned orchestras all over the world, such as the

Mariinsky Orchestra in St. Petersburg, the Great Symphony Orchestra Moscow,

the China Philharmonic Orchestra, the KZN Philharmonic Orchestra Durban,

the Georgian Chamber Orchestra, Sinfonia Varsovia and many others.

Every summer Frantz invites musicians from all over the world to his music

festival Finca Festival Frantz & Friends in Monte Leone.

|

Justus Frantz was in Chicago with the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra in February

of 1991, marking the 200th anniversary of the composer’s death.

The concert held two concertos, #20 in

d minor, K. 466, and #21 in C major,

K. 467, as well as the Jupiter

Symphony, all led by Hans Graf.

The pianist arrived a couple of days ahead of the performance, and we arranged

to get together for an interview. His English was quite good, though,

as usual with Europeans, his sentence-structure was often of the old-world

variety. I've straightened out most of the syntax, but some charming

varieties and usages have been left in where they do not interrupt the flow

of the words. Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere

on this website.

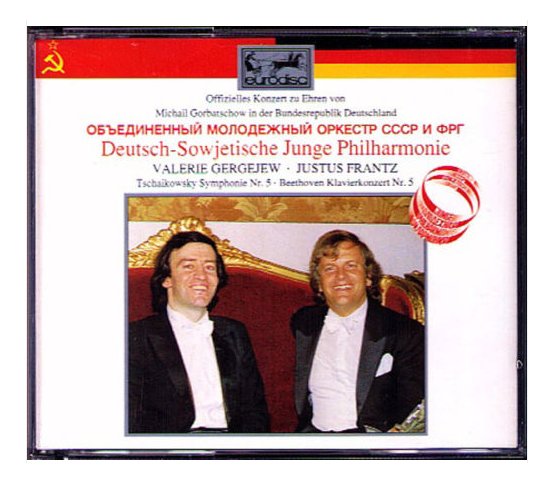

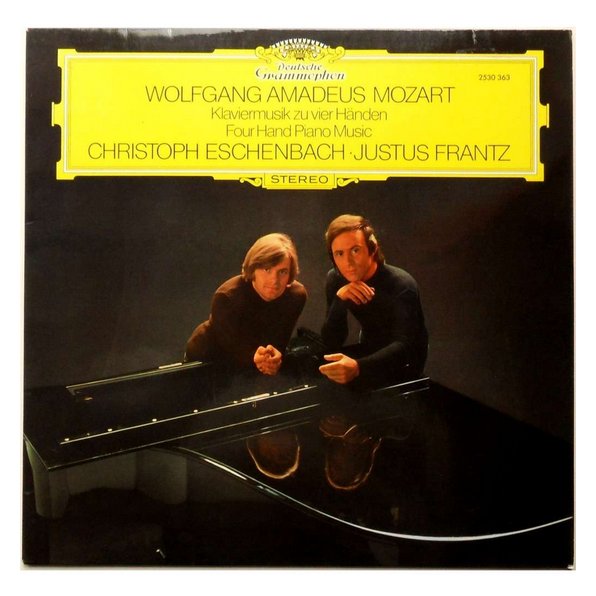

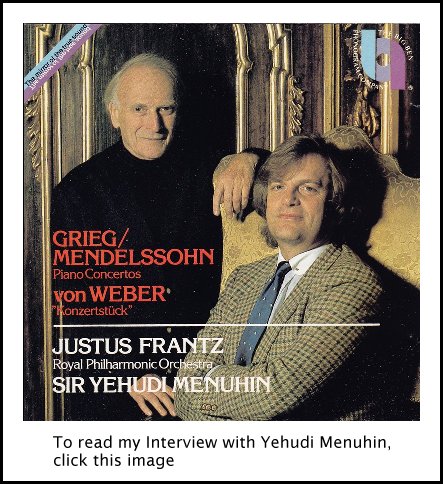

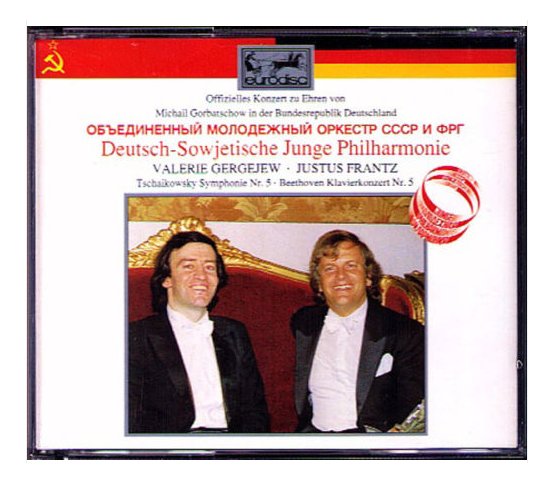

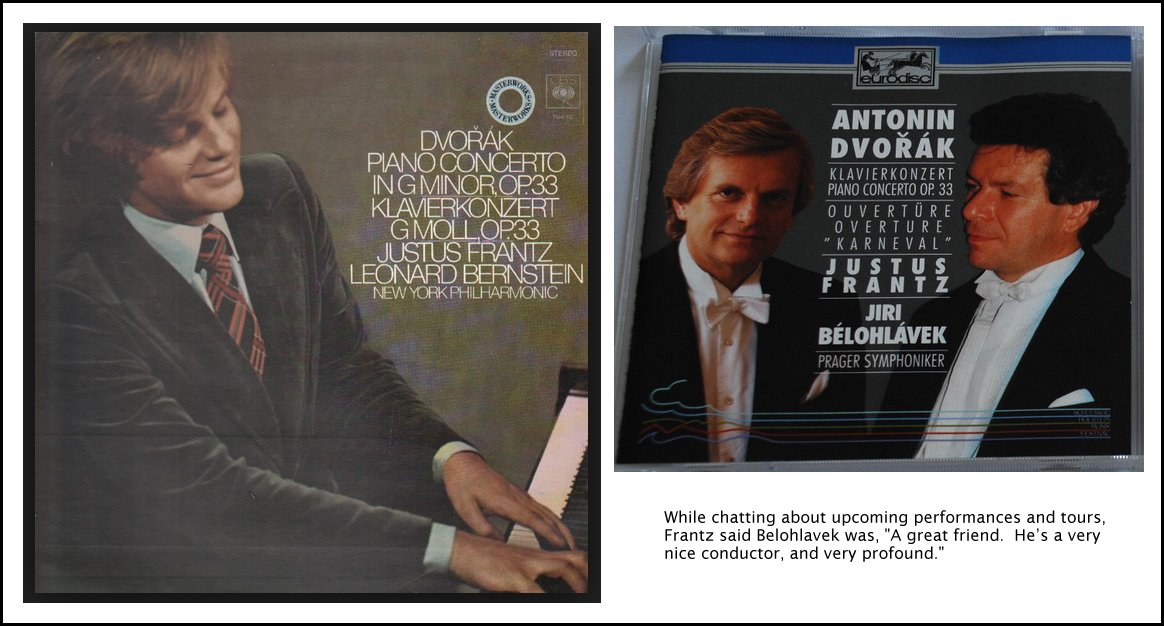

As we sat down for the conversation, we were looking at some CDs he brought,

including one that was quite special . . . . . . . . .

Justus Frantz: I founded that orchestra, the German-Soviet

Youth Orchestra. It’s a very good orchestra. You see, we were

always enemies, and suddenly we were together with the music, and it was

such an enjoyment. Everybody tried to be better. The recording

is of the whole concert, even with the National Anthems! Being a concert

we have no chance to repair it! [Both laugh]

Justus Frantz: I founded that orchestra, the German-Soviet

Youth Orchestra. It’s a very good orchestra. You see, we were

always enemies, and suddenly we were together with the music, and it was

such an enjoyment. Everybody tried to be better. The recording

is of the whole concert, even with the National Anthems! Being a concert

we have no chance to repair it! [Both laugh]

Bruce Duffie: Do

you prefer making records in live concerts?

JF: Somehow the

last times I only did live concerts. I did one with Vladimir Spivakov

and the Moscow Virtuosi, a middle Mozart concerto, and I’m very proud of

it. I’m also proud of Valery Gergiev, who is

a wonderful conductor, to do this Beethoven. I remember in the beginning

I really had to fight for the right way because he played it a little bit,

in my opinion, like Tchaikovsky. Maybe I played Beethoven too

German for him, and so after a while we met and we both are very happy with

the product of this Fifth, Emperor Concerto.

BD: You say you’re

looking for the right way. Is there only one right way to play any

piece of music?

JF: Of course there

isn’t, but in the moment you feel it and you want to be suggestive.

Then there’s only one way. Later on, maybe five years later, sometimes

you’re a little bit ashamed because you think there are lots of ways to make

music, but just the particular one you did five years ago, that’s not the

right way. [Both laugh]

BD: Has the music

changed or have you changed?

JF: Of course,

I have changed, yes, and my approach has changed. It is also the interesting

thing, and I must say I’m not interested in artists who always are doing

things the same way, because I find the most anti-artistic thing is reproduction

or repetition. It must be always a rebirth and it must be new.

It must be always full of strength, and so repetition is absolutely forbidden!

BD: Do you find

you change even from performance to performance on a given weekend?

JF: I would say

so, yes. Of course, I don’t want to change the law of the composer

and of what he has given to us, but from that moment on we have absolutely

liberty. For example, what does allegro

mean? It means ‘fast’, but what is ‘fast’? Today this is fast

for me, and tomorrow I might need it much faster, and after tomorrow I might

be much slower. That is very honest, and one has to do that this way.

BD: If your allegro is faster today, will your adagio be slower today or faster to keep

up in proportion?

JF: That has something

to do with the strength. If one can generalize, normally I would say

if you have played the first movement very fast, then the slow movement should

be a little bit slower to get the right architecture. But that is very

difficult. Every piece has its own cosmos and its own law.

BD: You have this

huge repertoire of piano music from which to choose. How do you decide

which pieces you will work on, and which pieces you might turn aside for

a while?

JF: That is a funny

thing. I decide like any pianist two, three, four years in advance

what I’m going to play. I’m sitting in the Canary Islands where I’m

working on my new programs, and suddenly I can’t work at what I want to work.

I’m seduced by playing some other music, and so sometimes I really have to

change because I must be honest. I’m so excited by some new piece that

I cannot follow the wishes I had spoken of two years ago, and I must play

something different. That doesn’t occur very often but sometimes it

does, and then I’m following this new idea.

BD: I assume there’s

too much music for you to do everything you want?

JF: Yes of course,

but I decided to play the three late Beethoven sonatas next year. I

played a lot of Mozart all these years, and suddenly I notice that

I never have played Beethoven sonatas in concerts and recitals. I might

have played one, but I didn’t play a whole recital. Maybe I thought

that this was apparently a little superficial, that it is not full of enough

contrasts for a whole recital. But now since I have played all Mozart

piano concertos, which I find is the heaven of music, now I want to do this.

So I change. I change because in this moment I’m in the world of music

of Mozart, and I’m very happy to play his sonatas, which he wrote in Paris,

so I make a program of Mozart in Paris.

BD: Is there a secret to playing Mozart?

BD: Is there a secret to playing Mozart?

JF: It is a line.

Unfortunately we don’t have a piano here in this room or I would show you!

I would say if there is a secret in playing a slow movement by Mozart that

it is singing. You really make a line, a long phrase, and not separate

each phrase by having it cut at the Schwerpunkt

[the focal point].

BD: You don’t want

a separation?

JF: No, no, no,

no, no. For example, in the slow movement of the Bb Major K. 595, [begins to sing it]

it’s going to the second bar of the phrase, and there is the high point.

But many people and pupils are playing [sings again, showing the lack of

phrasing], and then they already have three chunks. That is absolutely

what Mozart did not want.

BD: So there is

no accent on every bar?

JF: Yes, exactly

yes. No accent, and always, or nearly always, in the music of Mozart

there is an upbeat to himself. For example, every theme that I know

he has written that way. In the A

Major Concerto K. 488, [sings again] it goes to the second bar, and

it doesn’t start [sings, giving an accent on the first beat]. This

is also in the K. 467 Concerto,

which I will play tomorrow.

BD: So it’s always

going someplace!

JF: It’s always

leading to something, yes. That is really a law of Mozart.

BD: So you always

have to look ahead?

JF: Yes.

That propels his architecture

BD: Are there any

other composers who do this same kind of thing with the long line?

JF: No. No

one else is like Mozart doing that, absolutely not.

BD: Why hasn’t

some other composer picked up on it?

JF: Other composers

are more on earth than Mozart. For example, Beethoven is standing with

both feet on the ground, and that’s why he needs more accents. His willpower

is there from the first moment. There is not baroque bowing like Mozart.

BD: Do you find

that Mozart is more in the style of Telemann???

JF: No, I meant

not musical-baroque, but baroque in the way of history. When people

turn and are bowing like this [demonstrates] ...

BD: Using the grand

gestures?

JF: Yes, the grand

gesture, yes.

BD: It is more

elegant?

JF: It is a very

much more elegant, absolutely, yes.

BD: Are people

who are living in the 1990s, who have come through a couple of world wars

and depressions ready for the elegance that Mozart put into his music?

JF: I find it more

necessary than ever to hear the Mozart in this time, when after one year

of hope for all of us, suddenly we come back to the threat of a war.

I was just in the Baltic States, and I looked especially for Mozart, for

concertos for hope. The last concerto, the Bb Major, is a concerto of hope.

I played it just for my friends there because nobody is helping them.

They want to be independent, like they used to be until 1940 when Hitler

and Stalin decided to over-rule them. Since then they’re suffering,

and they need independence like any other country in the world. They

have determination...

BD: And music can

help this?

JF: Yes, yes!

Music can help because what we all need is hope, and this is what he composed;

hope is what Mozart has written there.

BD: Is music in

itself political?

JF: In itself it

is not political. It is too abstract, but it is also humanistic.

That’s what I believe in, and so it always, at least for a moment, can help

people to become better. As long as somebody is listening to Mozart,

he’s not shooting. [Both laugh]

BD: [Pursuing the

point] The same cannot be said if someone is listening to Hindemith

or Wagner?

JF: Well, of course,

yes, yes. The approach of Hindemith or Wagner when they’re understood

rightly also goes into the same direction, but Mozart is maybe the profoundest

of all. For me, at the moment, that is the case.

BD: Was Mozart

not human?

JF: He was very

much human but somehow it appears to me that he had a direct way to also

become an angel, at least in music.

BD: So he’s divine?

JF: He’s a divine

composer, yes, and he has probably a direct transmitter for divine music.

I hope I am communicating my ideas correctly...

BD: They’re coming

across very well. I’m glad you’re able to give your ideas in thought

as well as in music.

JF: I hope I can

do it better in music! [Both laugh]

* *

* * *

BD: Do you like

being a wandering minstrel?

JF: What is a wandering

minstrel?

BD: A performer

who travels all over the world... a jongleur!

JF: [With a big

smile] Oh, jongleur!

Yes and no. Sometimes it’s a little bit too much. Normally I feel

like a musical gypsy going through the world because I’m at home when I have

my keyboard with me. I couldn’t travel so much without music, but with

music it doesn’t take too much effort from me. I feel at home.

BD: The keyboard

that you travel with, it’s not a sounding keyboard is it?

JF: No, no.

It’s a silent keyboard, and of course it cannot replace a piano. But

today, for example, I will go to Orchestral Hall for some hours later on.

To learn a new piece it’s perfect on a silent keyboard because your fantasy

has to be much stronger than just the piano.

BD: So there is more heart in it?

BD: So there is more heart in it?

JF: Yes, and the

pre-imagination is much clearer.

BD: As you go around

the world you have new pianos to try each time. How long does it take

to make each piano your own?

JF: That’s a difficult

question because I don’t think that every time you can make the piano your

own. Sometimes pianos are using you, and you are playing a different

way than you are used to playing because the piano is in its beauty with

the treble section, so wonderful that you must use that. Even you have

thought about accents in the bass, because the bass is horrible you can’t

do that. So there’s always an inspiration of the piano to yourself,

and you achieve that. You also have the hall with the piano, and again,

in certain ways you try to change a little bit. You have to change,

otherwise it doesn’t work. Sometimes you are better than the piano,

and sometimes you have the feeling that the piano is better than yourself,

and that is the most inspired moment. Very, very seldom, I would say

out of fifty concerts there is just one where you really feel that the acoustics

are such that with the piano you can achieve a hundred per cent of what you

wanted, and everything is fulfilling your wishes.

BD: I assume, though,

that there are times when you achieve things you didn’t think you could do?

JF: Yes, very often.

That depends on some of the beauty of the acoustical of the piano... and

also of the public! They can be an enormous inspiration when you’re

playing a slow movement. When you try to make an enormous tension with

the pause and you suddenly notice that they’re really following, and they

are really appreciating this. You feel the tension in the hall, and

then you are inspired and you are maybe better with this public than you

are alone at home.

BD: Are the publics

different from city to city and country to country?

JF: Oh yes, very

much so. I must say on this tour we had a marvelous Mozartian public

in New York. They were so silent and attentive, and when we really played

a pianissimo there was not one cough.

It was wonderful! In Italy, people are not really wanting much in the

slow movement. They’re much more for the fast movements, and there’s

always a lot of coughing in the slow movement. They’re only waiting

for when it starts to become fast again. In Russia they love Mozart

more than I thought. Maybe they love Mozart the most, at the moment

at least.

BD: [Surprised]

More than Tchaikovsky?

JF: I have the

feeling, yes. We played the last week in Moscow only Mozart, and people

were standing around the Bolshoi Hall half a week in order to get a ticket.

And that is for Mozart! I had the same experience with Sviatoslav Richter

and his December festival in Moscow. There was the same thing, so people

want to listen to Mozart in Russia.

BD: More than just

they want to listen to great music?

JF: Well, I think

there is a contradiction which you don’t mean, because Mozart is great music.

BD: [Smiles]

I mean more than the general picture of great music?

JF: Yes.

Probably they seldom have more than Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninov or the banging

pieces. [Both laugh]

BD: [With a gentle

nudge] Mozart is never bangy?

JF: No, but I don’t

believe in a ‘sugar Mozart’.

I believe in a Mozart which also has both sides, like in these two concertos

I will be playing here, the C Major,

which is full of enthusiasm and of optimism, and then the abstract, contradicting

D Minor, which is abstract and demonic

and full of passion. Sometimes you don’t know where it’s going to go,

but the feeling of death in one concerto and the feeling of life in the other

concerto are the two sides of Mozart, and with all the passion I feel this.

I wrote a lot of cadenzas to these Mozart concertos. Often Mozart didn’t

write one, or we don’t have them. That’s also a big joy to play your

own cadenzas. For the D Minor,

of course you must play the one by Beethoven.

BD: [With mock

horror] You must???

JF: Well, I must!

I never tried to compose my own cadenza for this one because I feel nothing

can ever replace this cadenza that Beethoven wrote. It’s a wonderful

cadenza.

BD: Have you ever

gotten through a work and then decided to improvise your own cadenza as on

the spot?

JF: Yes.

I did it on a tour with a conductor who said to me that he didn’t like the

idea that cadenzas are always the same. So I said to him I would do

something. Just before coming out on the stage, he was to give me a

little theme, and I would improvise and combine it with themes of the concerto.

So we did it, and we started of course with Mozart, and it was very nice.

But then the stupid man started to ask me for things like Sacre du Printemps and even Mathis der Maler. [Both laugh]

We got a very funny review because the critic wanted to know what we did

with the cadenza. Why was it suddenly that modern? But we had

a good time.

BD: But isn’t that

the purpose of the cadenza to improvise?

JF: Yes, it is.

Sometimes I’m doing that, but normally conductors don’t like that because

then they are very frustrated because they don’t know when to enter!

BD: Won’t

they just wait for the trill?

JF: Yes, but this

is something I don’t like so much. I like nice scales when it really

runs into the orchestra, and that is always intimidating enormously for conductors.

I remember once there was suddenly silence after ending the cadenza, and

then suddenly the orchestra came in. After that the conductor was never

very friendly to me!

* *

* * *

BD: How do you

divide your career between solo recitals and concerto performances?

JF: I must say

that I give many more concerts with orchestra. That depends, for example,

on the twenty-seven Mozart piano concertos, which I so much love to play

at the moment, but I only have two programs of Mozart sonatas. I need

much more time in order to play all of the concertos, and we do this in series

in different cities in Europe — Berlin, Munich, London,

Paris, and so on. I would say I play seventy per cent with orchestra

and thirty per cent recitals.

BD: Do you ever

conduct from the keyboard?

JF: I started as

a conductor. I never conducted from the keyboard, but I conducted The Magic Flute in Hamburg nearly fifteen

years ago, and I might conduct again this year. Then I will invite

all my friends, and they will say this is good or not good! I have

a feeling I would like to continue my relationship with conducting.

BD: For a concerto

performance you have yourself and your own ideas, and you have the conductor

with his or her ideas. Are they always in sync?

JF: A ‘concerto’ sort of means

competition. ‘Concerta’ means

‘we are fighting together’ for the right thing. I find it very interesting

sometimes if the conductor and the soloist both are not always the same,

that they are striking a little bit, but on a friendly basis, of course.

Then that could really create another sort of tension in the concert, which

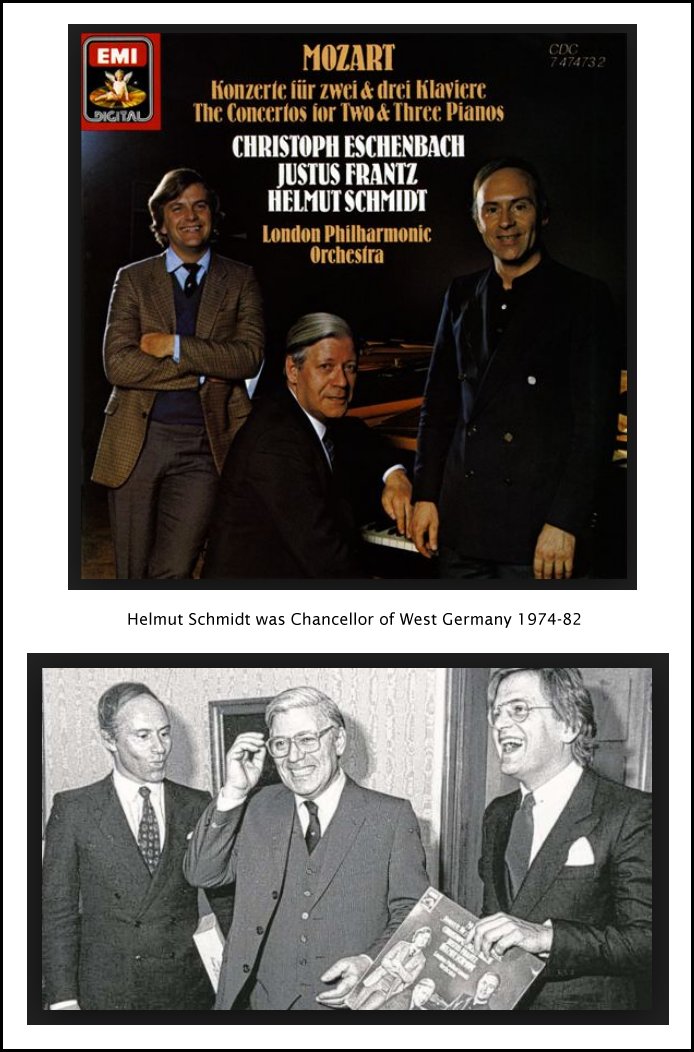

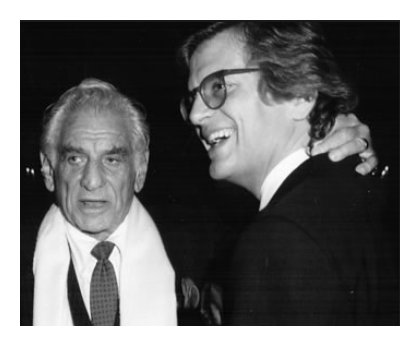

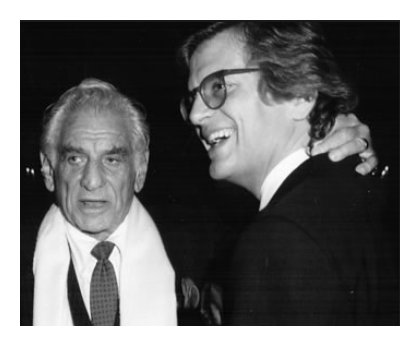

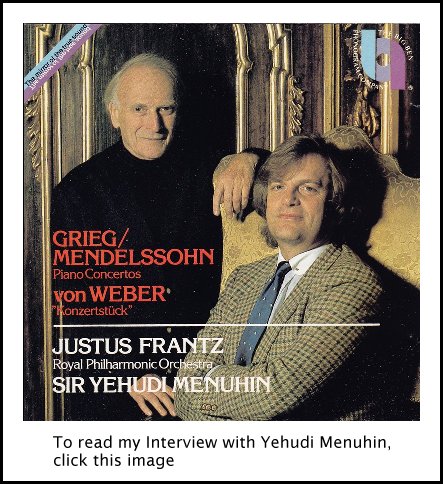

would be very nice. With Lenny Bernstein [shown with Frantz in photo at right]

I had this experience very often, because he was a completely different person

in a rehearsal than in a concert. I remember when we did the Schumann

Concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic

for records, we tried to do it, as he said, ‘feverish’! “The

Schumann fever should spread out over the concert,” he said.

But then in the concert suddenly he was half as fast, or doubly as slow than

in the rehearsal!

JF: A ‘concerto’ sort of means

competition. ‘Concerta’ means

‘we are fighting together’ for the right thing. I find it very interesting

sometimes if the conductor and the soloist both are not always the same,

that they are striking a little bit, but on a friendly basis, of course.

Then that could really create another sort of tension in the concert, which

would be very nice. With Lenny Bernstein [shown with Frantz in photo at right]

I had this experience very often, because he was a completely different person

in a rehearsal than in a concert. I remember when we did the Schumann

Concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic

for records, we tried to do it, as he said, ‘feverish’! “The

Schumann fever should spread out over the concert,” he said.

But then in the concert suddenly he was half as fast, or doubly as slow than

in the rehearsal!

BD: So it was completely

different?

JF: It was completely

different, and I was really shocked. It came out later on when we heard

it on the tapes. We couldn’t combine anything from the concert with

the rehearsal, but it was marvelous because somehow you could feel the tension

between conductor and soloist. It was a fight for the right tempo!

BD: [Playing Devil’s

advocate] So why do you rehearse if you’re going to change

things around in the concert?

JF: Well, that’s

a good question. [Both laugh] In this case Lenny was absolutely

contrary of Karajan. Karajan was very difficult to rehearse with, but

then he was so reliable and he was just fulfilling what one time he had done.

Lenny was swept away by new ideas and by wonderful new fantasies, and so

everything could be changed. So both sides were wonderful, and great

gifts into my life experience.

BD: It seems that

those two conductors are opposite ends of the spectrum.

JF: Absolutely,

for me, yes they were.

BD: And yet you

could deal with both of them?

JF: Yes, of course.

With great things, one always wants to deal. They were both great characters.

BD: Tell me about

the Schumann Concerto. Is

that a special for you, or is it just another concerto?

JF: I don’t have

such things like ‘another concerto’. Always these are friendships which

are lasting for the whole of my life. The Schumann Concerto is a piece which I heard the

first time from the last pupil of Clara Schumann. That was a grand

aunt of mine, who was a pupil of Clara Schumann. I remember I was five

or six or seven years old. It was just the beginning of the ’50s,

and she was still alive. She was nearly 100, and she played the Schumann

Concerto and very much other of

his music. That was an enormous impression on me. From this moment,

Schumann’s music has always accompanied my life. I feel the obsession

in Schumann. I feel his fear and his humanity. Schumann is a

composer I really would have loved to become a friend because somehow I feel

enormously sympathetic with him. I am a Schumann-being! [Both

laugh at the pun]

BD: Do you feel

you could have rescued him from his madness?

JF: I would give

everything to do that, but no. In his diary and in his letters and

mostly in his music, it’s so full of heart. Even little phrases are

so full of poetry, which somehow touches me very much. And when he

becomes ill, his music brings me into tears. Such a piece like the

Requiem, or other very late pieces,

when he really has difficulties to find forms and to express himself and

find the right orchestration, somehow it is like seeing someone you love

getting older and becoming feeble. Such a feeling I have with his music.

BD: Have you given

any thought to playing any of Clara’s music?

JF: I was thinking

to play her Piano Concerto.

Maybe I’ll be able to do this sometime.

BD: It would be

interesting to see what you could bring to that, or what you could find within

the score.

JF: Yes, but at

the moment I’m on the way through the world of Robert. I think about

how long I will still be in this world.

BD: It would be

interesting to see if you could find the relationship between his music and

her music, and the influences back and forth.

JF: Yes, yes, absolutely.

There are the Variations on a Theme by

Clara Wieck. Maybe some dreams are ending when they are fulfilled!

[They both laugh again]

* *

* * *

BD: Let me ask

the big philosophical question. What’s the purpose of music in society?

JF: That’s more

a sociological than a philosophical question. For me it’s quite easy.

I became a musician because I need spiritual meanings in this world, and

for me music is the language of God. I find God by making music, and

I need this. I find that in a world which is overflowing with information

and by consumerism, it is so eminent. It is necessary also to have

a world which never can be materialistic, and that’s why music is maybe more

important for all of us than it was ever before.

BD: Do you feel that you’re a musical missionary?

BD: Do you feel that you’re a musical missionary?

JF: I feel that

everybody who is listening to music is listening to a sort of mission, yes.

BD: Is it your

mission, or is it Mozart’s mission?

JF: I don’t know.

I think it is a mission which is the beginning. From the Bible, “In

the beginning was the Word,” and that was the sound

and was the logic. I find that music is the expression of this law

of construction of the cosmos.

BD: Do you feel

that all of the great music in the world comes directly from God?

JF: Yes, I feel

that. I believe music is always under these laws, and so I actually

feel we are all interested in what composers were doing during their lifetime.

But whether Wagner was wearing a beret or not doesn’t make any difference.

The music is somehow a miracle that through him came to birth and to the

world.

BD: Does that miracle

continue today with the composers who are righting now?

JF: I hope that

is the case. It is very difficult for us to speak about that because

it is too new. But I would say that composers like Ligeti, like Schnittke,

maybe Berio, to name

three of them, are composers which also will last for a long time, and also

will be under these laws.

BD: Do you play

some of this new music?

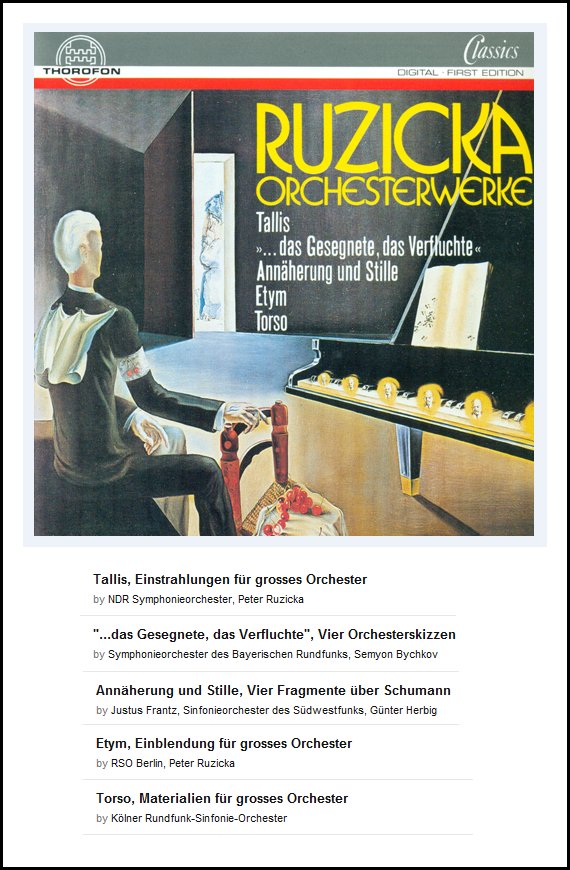

JF: Yes.

I played music by Ruzicka [photo of CD

booklet shown later on this webpage], by Henze, by Stockhausen and

Schnittke... not so much in this moment, since Mozart is such an enormous

amount of work. The new scores are not striking me in the moment very

much, but normally I do play some.

BD: Do you feel

that the spirit of Mozart is applauding the new efforts?

JF: I hope so!

[Both laugh]

BD: Let’s talk

a little bit about your festival in Schleswig-Holstein.

JF: Schleswig-Holstein

was born as different festivals, because different festivals have their own

spirit and also sometimes their own mistakes. In Europe, music is much

more of an elite class than in America. If you are in Berlin you have

this avenement [advent, coming].

For example, every second Monday you are always listening to the Berlin Philharmonic.

BD: Oh, a series?

JF: A series to

which you are subscribing, yes. We call that avenement, and normally in cities we have

a very old public because you get it passed to you from your dead father.

You get the second Monday series, and you give it to your son, and so on,

and so on! In Salzburg the prices are immensely high, especially for

young people, and so I thought that ours must be a festival which is little

bit similar to Tanglewood or Blossom, or even here the Grand Park concerts

in Chicago. So we spoke with Lenny Bernstein about this, and we thought

we must combine different things. We must found a school which brings

different, wonderful teachers from all the world to Schleswig-Holstein, which

was the place actually we spoke about back then. We must bring an orchestra

together with youngsters from all over the world to create and to show as

a symbol for a world that could do much better if it would be more symphonic.

We should like to bring young musicians and give them the same platform like

the big stars of music. That was all very difficult to create, but

it worked out. We had 250 concerts which were sold out normally, but

if we had a long line of people, we just opened the doors and let them in.

That was good for the spirit. Midori was there, as was Vengerov, and Kissin

was there for the first time outside of Russia. He was in the first

concert, and everybody knew that a new star from Russia was born. So

throughout these years the youngsters created an enormous interest, and they’re

not playing for a small public or just your family — which

is so frustrating for young musicians — but for a really

big audience. We have the same amount of people that Lenny Bernstein

has. We also want to bring modern music. Lenny conducted for

20,000 people things like Sacre du Printemps.

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony for 20,000

is nothing, but Sacre, and then the

Fifth of Sibelius, these are not

pieces for the general public, but they were enormously accepted. So

this festival is now ready, a very nice part of the big European festival

scene. We didn’t want to add just another festival. We wanted

to do something which others are not doing. We want to bring the youth

aspect — education, modern music, young composers,

young instrumentalists. We want to make it as part of the villages,

to bring music we have not only to people flowing in from Salzburg and New

York, but also we want to do it for the farmers and for the people in the

villages. That sort of modern musical democracy has worked out.

BD: So you feel

that concert music is for everyone?

JF: Of course,

it’s for everyone. It would be as stupid to say it should only be for

the inner circle! It is like a religion, and how could we ask people

not to go to church? It must be open for everybody, yes.

* *

* * *

BD: I want to come

back to the idea of recordings. Do you play the same in the recording

studio as you do in the concert hall?

JF: The question

in recording studios is how often do you have to play something and always

be inspired by it. For example, we had sometimes in a recording enormous

problems with woodwinds. They were out of tune, and so I played three

bars and they were already too low or too high. That was going up and

down, and we had to repeat and repeat it. After a while I said I don’t

want to do that anymore because twenty times, or a hundred times, you cannot

say ‘Ich liebe dich’ with the same

passion. It’s only the surface, but it’s not deep and profound anymore.

BD: And yet in

a concert, if there’s a little bit which is out of tune you just have to

go right on.

JF: Yes, and sometimes

it matters so much more. But of course a recording engineer is looking

for surface that must be perfect. We, the public and the artists, are

looking more for the profoundness of interpretation.

BD: What about

during a solo recital when you are the only one there?

JF: Then I like

very much to do it in a recording studio because you can stop if you feel

you are getting tired, or you’re not that inspired. Then some hours

later you start again, and hopefully the enjoyment and the joy of music will

be bring you to new inspiration.

BD: Are you pleased

with the recordings that have been issued of your music?

JF: That is a difficult

question. If I say no, then it’s not good, and if I say yes, it’s immodest.

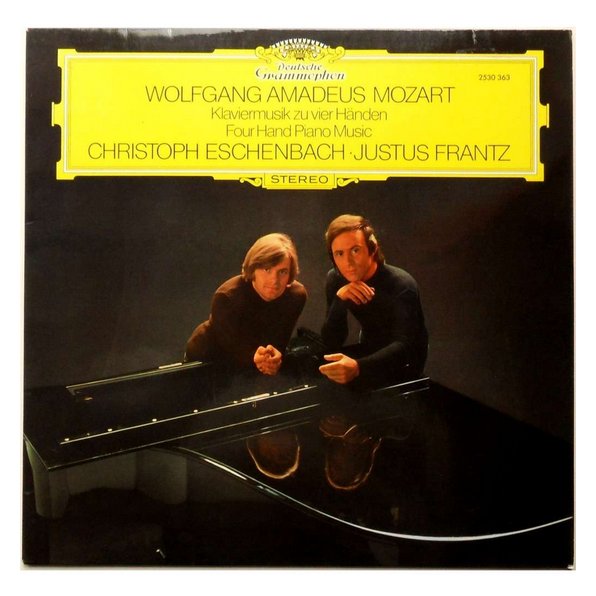

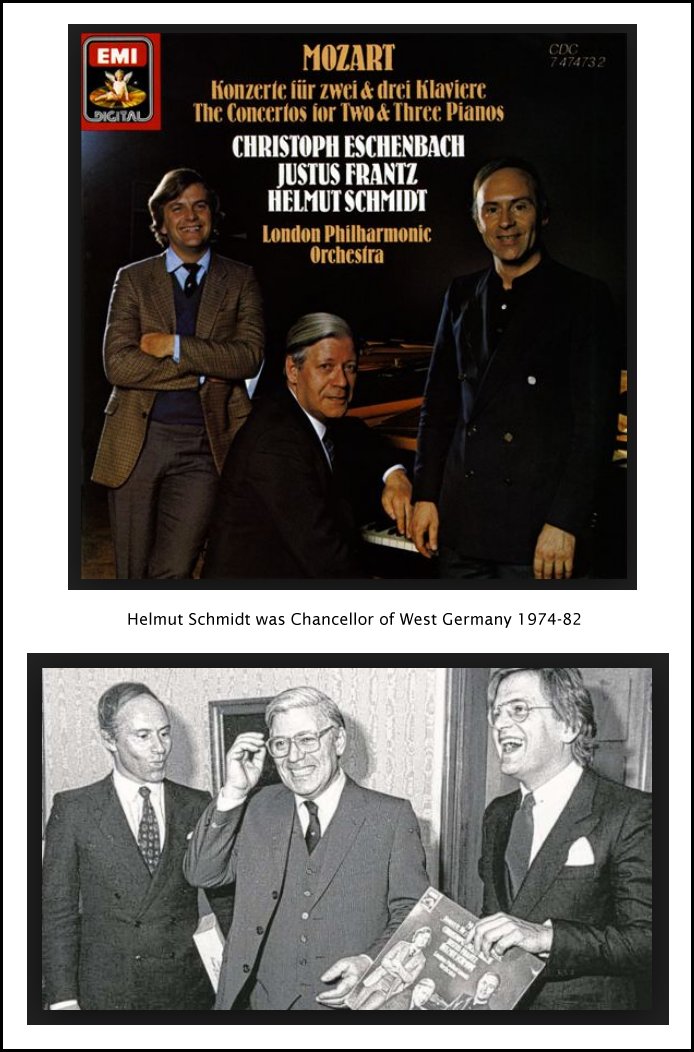

But I would say I think that’s what I wanted to do, at least with the Mozart

and with the Dvořák and the Beethoven Emperor.

BD: Tell me about

the Dvořák Concerto.

JF: The Dvořák!

Dvořák has written a piano concerto that really

is extremely difficult to play because Dvořák

was not a pianist. He wanted to sound like Brahms, but he didn’t know

how to do it. So it’s very combined like a cello with a violin, and

he wanted the piano to be banged like Brahms or Tchaikovsky, and that is nearly

impossible. So even it’s harder than a Brahms concerto.

It doesn’t transmit to the public, and so pianists don’t like to play it

so much because nobody knows how much work is in it.

BD: And yet you

have to bring this music to the public.

JF: Yes, but I love this piece. It’s very

unfortunate that it is forgotten by so many pianists. I find it in

the ranking of Romantic piano concertos beside the famous concertos like

the Brahms concertos, the Tchaikovsky, the Grieg, the Schumann... [pauses

to think]

JF: Yes, but I love this piece. It’s very

unfortunate that it is forgotten by so many pianists. I find it in

the ranking of Romantic piano concertos beside the famous concertos like

the Brahms concertos, the Tchaikovsky, the Grieg, the Schumann... [pauses

to think]

BD: The Beethovens?

JF: Beethoven?

You think Beethoven is a Romantic? I leave him to the Classic Period.

BD: I thought at

least the last two concertos would be into Romantic realm.

JF: Yes, maybe.

I also play Beethoven, but I’m speaking about the second half of the last

century. The Dvořák Concerto for me really comes much before

Liszt. I find it much more musical, much more honest and finer than

the Liszt concertos. But of course if you play Liszt, you get a standing

ovation you never get with the Dvořák.

[Both laugh]

BD: Is the public

missing what is in the Dvořák?

JF: Maybe it is.

It’s such a big orchestra. The piano, as I said, has not the banging

octaves. It has a lot of other difficulties, but when it does not create

the big sound, maybe sometimes they don’t listen. Maybe they cannot

hear you the subtleties. I don’t know. I really only hear this

piece from the stage or from the records, but the first movement has great

architecture. It’s great symphonic work, a wonderful sonata movement.

The second movement is a wonderful creation, and the third is like a picture

book of Slavic countries with its beautiful themes. Of course the last

movement with its different Slavonic themes is very long, and so George Szell,

for example, tried to do it with a short cut, which I found I don’t like,

I must say.

BD: You don’t like

the cut?

JF: No, absolutely

not. I like every note from the first single note to the last.

Maybe the other way is more successful, but I like my way better.

BD: [With a gentle

nudge] You like Dvořák’s way better?

JF: Yes, that’s

right, yes, yes, very right. [Both laugh]

* *

* * *

BD: Is there a

competition amongst pianists in the world?

JF: [Thinks for

a moment] Actually if you are speaking of playing faster and louder,

then there would be a competition. But in a way that a music should

come to be given by an individual soul to the other individual souls, then

there is no competition because there is not, for heaven’s sake, a competition

between souls. This kind of competition, which apparently we are all

accused of, is not for me.

BD: You’re also

teaching at the Hochschule?

JF: Yes.

BD: Is this piano

technique or repertoire, or what?

JF: We include

all of this. I’m teaching piano technique and repertoire in what we

call a masterclass, and I’m also teaching sometimes management through the

festival. Our young artists can come and help in the festival so they

learn something about the organization of the musical world. That way

they’re a little bit more self-determined, and they know better what they

want and are not simply delivered to the power of the big managers.

BD: Like lambs

to the slaughter!

JF: [Laughs] Yes!

JF: [Laughs] Yes!

BD: What advice

do you have for young pianists coming along today?

JF: I would say

the most important thing is that we must strike against the danger of the

electronic media which makes products that are clean and perfect by using

many takes and cutting the best parts together. In a concert you can

try to be the same as on the recording, but then very often it destroys the

profoundness of music. It’s wonderful if you can do it, but it’s not

the main point. The main point is that you have a birth of fantasy

and of temperament, and that must be striking. It is much more important

to show the great architecture of music. Beethoven had one pupil, and

he delivered a very famous word of Beethoven. He played at one time

the Appassionato to the composer,

and it was perfect. Not one wrong note. Beethoven was listening,

and then he said, “But really nothing happened!”

That is sometimes unfortunately what is appearing for us in concerts today

— nothing happens. Everything is

clear and not one false note happens, but also there is nothing of the soul,

of fantasy, of striking new things in the concert.

BD: So the performer

should make something happen?

JF: Yes, and the

biggest danger we are confronted with at the moment is the sterility of concerts.

That is because we try to imitate. We don’t try to follow the great

moments of art, but we follow great records, and that is not good, of course.

We must be performers, not record reproducers.

BD: [With a sly

grin] Then why do you make records?

JF: Yes!

[Both laugh] The last record I did, I made in concert, and even this

is, hopefully, not for being repeated by others. Maybe it can inspire

somebody to do something new. That would be wonderful, but I don’t

want to have pupils who are doing exactly the same things I did, because

everybody is different.

BD: Is playing

the piano fun?

JF: Yes, a lot

of fun, yes. Yesterday, for example, I felt very bad in my body.

I had a very bad migraine headache, but I played Mozart, and from movement

to movement I felt better, and at the end I was cured.

BD: Mozart has

therapeutic value!

JF: Yes, but not

only Mozart. When I am in a depression, and I play sometimes Beethoven.

You can’t have a depression after having played the Emperor Concerto. You must be as

if the music came to your heart and your soul. Then you must be a proud

and vital human being after having played this work. I don’t understand

musicians who are always so exhausted after a concert because I feel music

gives you so much strength that I’m much better after a concert. We

could repeat this interview then, and you would see I know much better English

than I do now!!! [Both laugh]

BD: You’re keyed

up?

JF: Yes.

BD: I’m glad the

music gives you so much.

JF: Yes.

BD: Then you give

that to the audience?

JF: Yes, that’s

at least what I try, and in good moments that’s what happens.

BD: Thank you for

being a pianist. Thank you for being a musician.

JF: Thank you.

=======

======= =======

======= =======

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

======= =======

======= =======

=======

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 20, 1991.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following day, and again in 1994 and

1999. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website

at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97

in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other

interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with

comments, questions and suggestions.

Justus Frantz: I founded that orchestra, the German-Soviet

Youth Orchestra. It’s a very good orchestra. You see, we were

always enemies, and suddenly we were together with the music, and it was

such an enjoyment. Everybody tried to be better. The recording

is of the whole concert, even with the National Anthems! Being a concert

we have no chance to repair it! [Both laugh]

Justus Frantz: I founded that orchestra, the German-Soviet

Youth Orchestra. It’s a very good orchestra. You see, we were

always enemies, and suddenly we were together with the music, and it was

such an enjoyment. Everybody tried to be better. The recording

is of the whole concert, even with the National Anthems! Being a concert

we have no chance to repair it! [Both laugh]  BD: Is there a secret to playing Mozart?

BD: Is there a secret to playing Mozart? BD: So there is more heart in it?

BD: So there is more heart in it? JF: A ‘concerto’ sort of means

competition. ‘Concerta’ means

‘we are fighting together’ for the right thing. I find it very interesting

sometimes if the conductor and the soloist both are not always the same,

that they are striking a little bit, but on a friendly basis, of course.

Then that could really create another sort of tension in the concert, which

would be very nice. With Lenny Bernstein [shown with Frantz in photo at right]

I had this experience very often, because he was a completely different person

in a rehearsal than in a concert. I remember when we did the Schumann

Concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic

for records, we tried to do it, as he said, ‘feverish’! “The

Schumann fever should spread out over the concert,” he said.

But then in the concert suddenly he was half as fast, or doubly as slow than

in the rehearsal!

JF: A ‘concerto’ sort of means

competition. ‘Concerta’ means

‘we are fighting together’ for the right thing. I find it very interesting

sometimes if the conductor and the soloist both are not always the same,

that they are striking a little bit, but on a friendly basis, of course.

Then that could really create another sort of tension in the concert, which

would be very nice. With Lenny Bernstein [shown with Frantz in photo at right]

I had this experience very often, because he was a completely different person

in a rehearsal than in a concert. I remember when we did the Schumann

Concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic

for records, we tried to do it, as he said, ‘feverish’! “The

Schumann fever should spread out over the concert,” he said.

But then in the concert suddenly he was half as fast, or doubly as slow than

in the rehearsal! BD: Do you feel that you’re a musical missionary?

BD: Do you feel that you’re a musical missionary?

JF: Yes, but I love this piece. It’s very

unfortunate that it is forgotten by so many pianists. I find it in

the ranking of Romantic piano concertos beside the famous concertos like

the Brahms concertos, the Tchaikovsky, the Grieg, the Schumann... [pauses

to think]

JF: Yes, but I love this piece. It’s very

unfortunate that it is forgotten by so many pianists. I find it in

the ranking of Romantic piano concertos beside the famous concertos like

the Brahms concertos, the Tchaikovsky, the Grieg, the Schumann... [pauses

to think] JF: [Laughs] Yes!

JF: [Laughs] Yes!