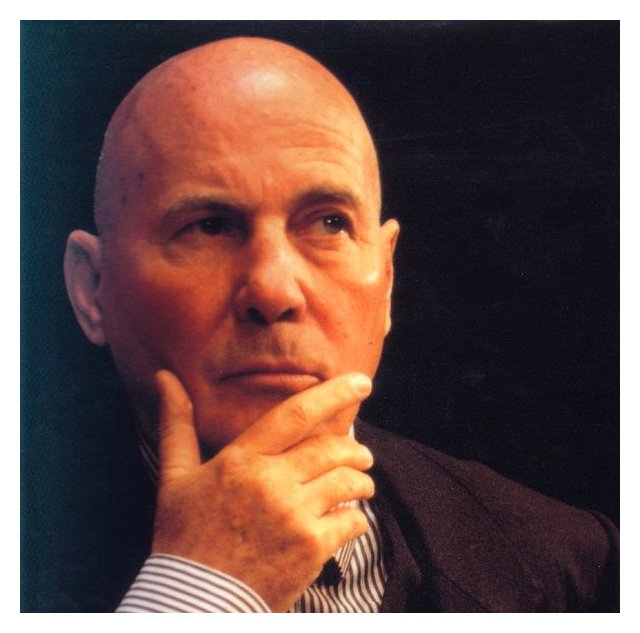

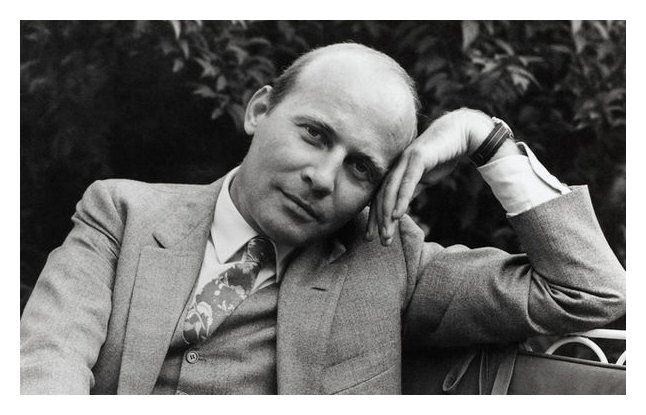

Born in Gütersloh on 1 July

1926, Hans Werner Henze received his earliest musical training at the

Braunschweig Staatsmusikschule. As a child, he witnessed the branding

of modern music, art and literature by the Nazis. After having worked

as a répétiteur at the Bielefeld Stadttheater Henze began

to study with Wolfgang Fortner at the Heidelberg Institute for Church

Music in 1946. In the late 1940s he came across serialism and began to

attend the Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music. After fulfilling his

engagements at the Constance Theatre and the Wiesbaden Hessisches

Staatstheater, Henze left Germany in 1953 and settled in Italy. It was

also the geographical distance to the German contemporary music theory

that helped him to achieve new varied forms of expression in his own

music. In the late 1970s and early 1980s Henze turned to more

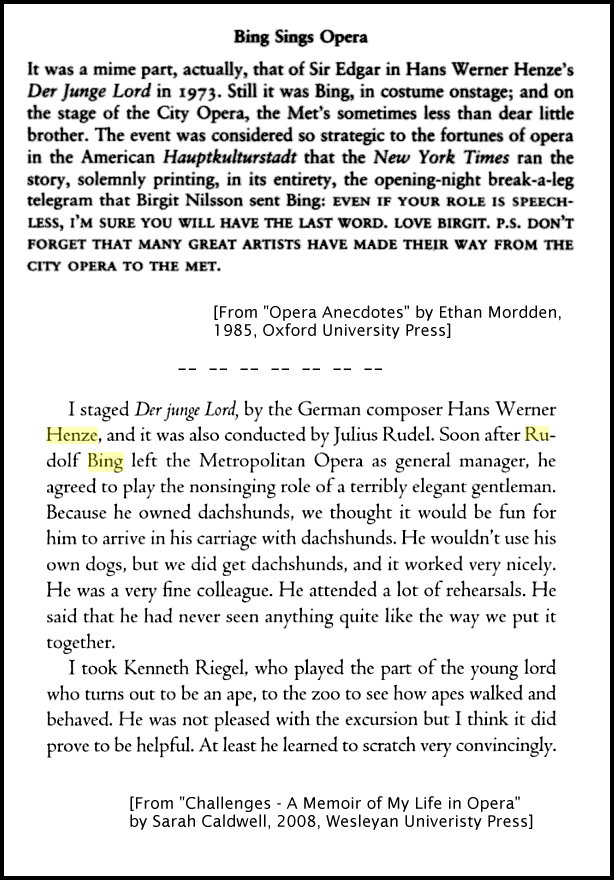

traditional forms. From 1962 to 1967 Henze taught a master class of

composition at the Salzburg Mozarteum while other teaching assignments

led him to the USA and Cuba. In Cologne Henze held a chair at the

Staatliche Hochschule für Musik from 1980 to 1991. In addition, he

was appointed composer-in-residence at the Berkshire Music Center in

Tanglewood/USA in 1983 and 1988-1996 as well as of the Berlin

Philharmonic Orchestra in 1991. In 1976 Henze founded the Cantiere

Internazionale d'Arte in Montepulciano and in 1988 brought the Munich

Biennial: International Festival of New Music Theatre into being which

he headed until 1996. Henze's oeuvre as a composer is very comprehensive: He

wrote solo concertos, symphonies, oratorios, song cycles, chamber

music. It was especially the works for music theatre that have made

Henze one of the most frequently performed contemporary composers of

our time. The radio opera version of his early opera Ein Landarzt based on Franz Kafka's

story of the same name was awarded the 'Prix Italia' as early as 1953.

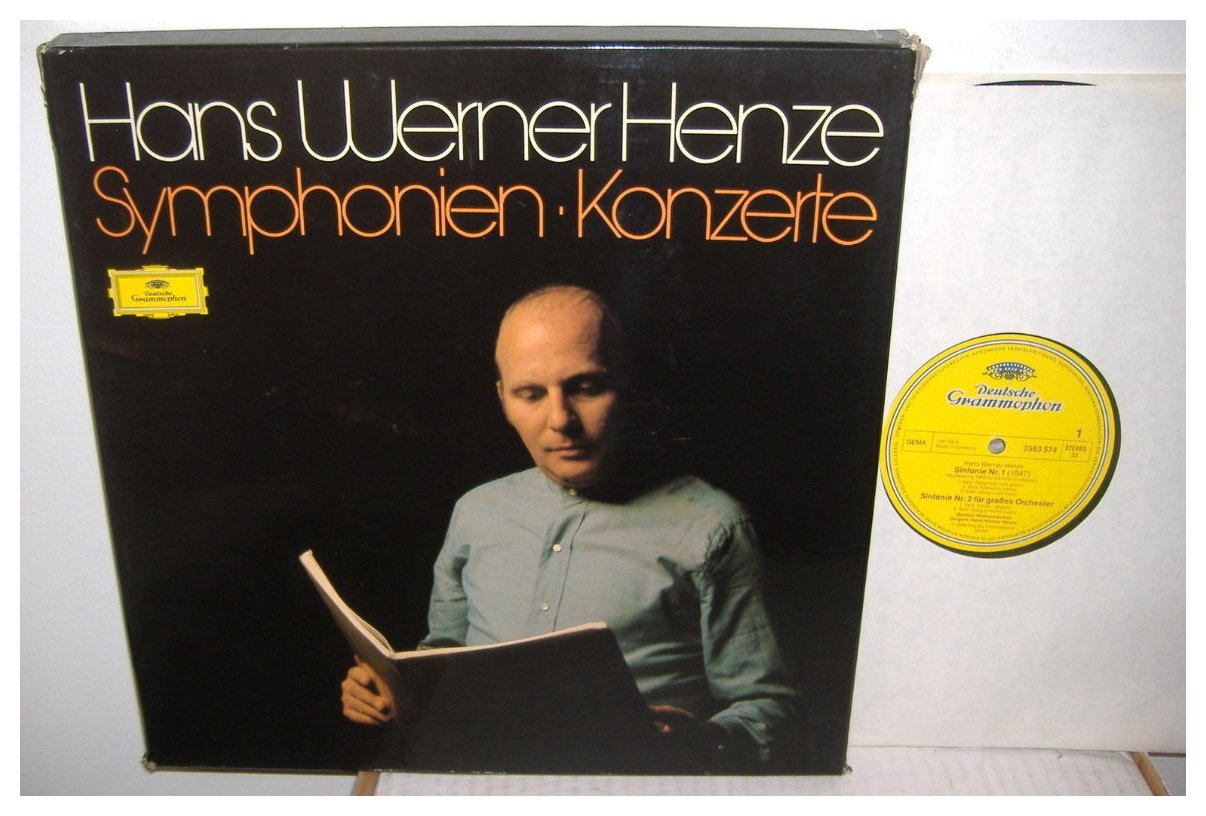

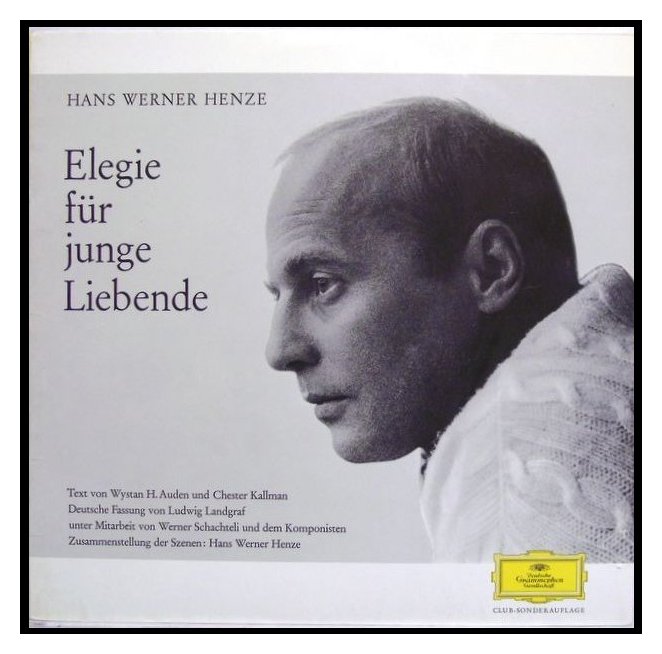

His varied opera repertoire includes works such as Das Wundertheater (1948/64), Boulevard Soltitude (1951), a

setting of the Manon Lescaut material, König Hirsch (1953-56), Elegie für junge Liebende

(1956/61, rev. 1987), Die Bassariden

(1964/65, rev. 1992), Pollicino

(1979/80) as well as 'Das verratene

Meer' revised in 2003/2005 (Gogo

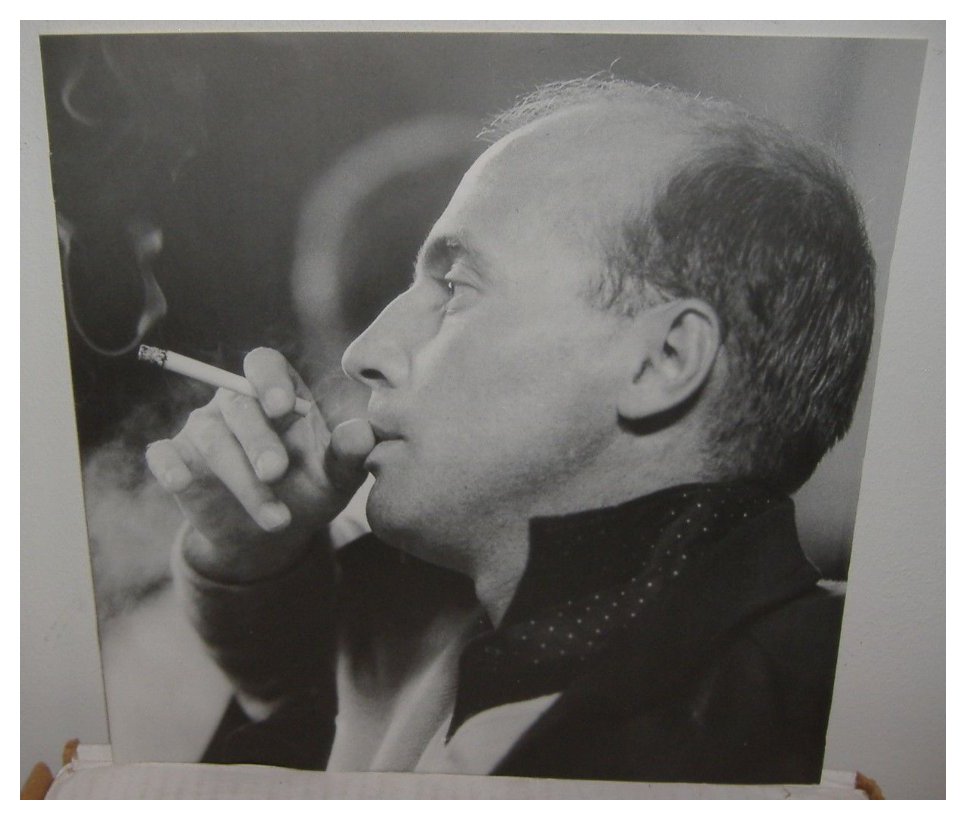

no Eiko, original version 1986/89). Henze entertained a close

relationship with Ingeborg Bachmann, their joint collaboration

resulting in works such as (1964), Der

junge LordDer Prinz von Homburg (1958/59, rev. 1991) as well as Nachtstücke und Arien for

soprano and large orchestra (1957). Henze's oeuvre as a composer is very comprehensive: He

wrote solo concertos, symphonies, oratorios, song cycles, chamber

music. It was especially the works for music theatre that have made

Henze one of the most frequently performed contemporary composers of

our time. The radio opera version of his early opera Ein Landarzt based on Franz Kafka's

story of the same name was awarded the 'Prix Italia' as early as 1953.

His varied opera repertoire includes works such as Das Wundertheater (1948/64), Boulevard Soltitude (1951), a

setting of the Manon Lescaut material, König Hirsch (1953-56), Elegie für junge Liebende

(1956/61, rev. 1987), Die Bassariden

(1964/65, rev. 1992), Pollicino

(1979/80) as well as 'Das verratene

Meer' revised in 2003/2005 (Gogo

no Eiko, original version 1986/89). Henze entertained a close

relationship with Ingeborg Bachmann, their joint collaboration

resulting in works such as (1964), Der

junge LordDer Prinz von Homburg (1958/59, rev. 1991) as well as Nachtstücke und Arien for

soprano and large orchestra (1957).In the centre of Henze's orchestral compositions are his ten symphonies, including Sinfonia N.9 for mixed choir and orchestra (1995-97) with verses by Hans-Ulrich Treichel based on the novel The Seventh Cross by Anna Seghers – an impressive example of Henze's examination of Germany's National Socialist past. Sinfonia N.10, commissioned by Paul Sacher, was premiered at a widely acclaimed performance in Lucerne in 2002 by the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Sir Simon Rattle. Among the numerous awards and prizes received by Henze are: 1990 Ernst von Siemens Music Award, 1995 appointment as Accademico Onorario of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Rome, 1997 Hans von Bülow Medal of the Berlin Philharmonic, 1998 appointment as Honorary Fellow of the Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester, 2000 Praemium Imperiale in Tokio, 2001 Cannes Classical Award in the category 'Best Living Composer', to mention but a few. 2003 saw his appointment as Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur, Paris and his receiving the Prize of the International Summer Academy Mozarteum 'Neues Hören' for the successful conveyance of new music. On the occasion of Henze's 80th birthday in 2006, numerous international concert halls, such as the Konzerthaus Dortmund and the Kungliga Filharmonikerna Stockholms Konserthus, dedicated special concert series to him. In 2007 the recording of Henze's melodrama Aristaeus with Martin Wuttke and the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Marek Janowski was awarded the Echo Klassik in the category 'Best First Recording of the Year'. [See my Interviews with Marek Janowski.] Henze died in Dresden on October 27, 2012. -- Biography from the Schott

Website (with photo and link added for this website presentation)

|

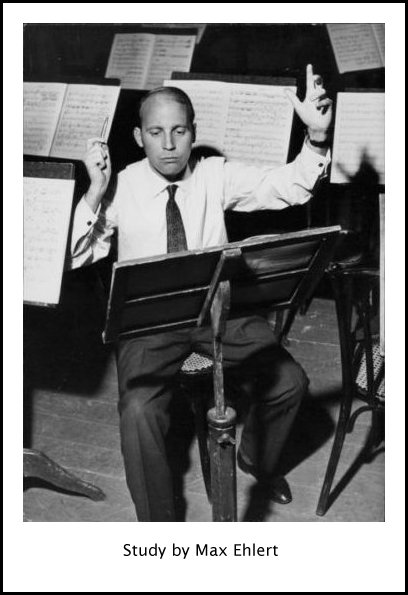

BD: Do you enjoy

conducting?

BD: Do you enjoy

conducting? HWH: No. I

wasn’t happy with my production of The

Magic Flute. It didn’t work. I tried to see it from

the angle of the freemasonry, and tried to get all that under control,

which is usually left aside a little bit, and in the mystery and in the

mist. I tried to depict the priests and Sarastro’s world as the

world of the illuminated, progressive people of that time, of Mozart’s

time, and Mozart identical with them and their aims, their humanitarian

aims.

HWH: No. I

wasn’t happy with my production of The

Magic Flute. It didn’t work. I tried to see it from

the angle of the freemasonry, and tried to get all that under control,

which is usually left aside a little bit, and in the mystery and in the

mist. I tried to depict the priests and Sarastro’s world as the

world of the illuminated, progressive people of that time, of Mozart’s

time, and Mozart identical with them and their aims, their humanitarian

aims. HWH: Oh, yes?

HWH: Oh, yes? HWH: That would be

rather taxing for the theater goers, wouldn’t it? The theater

goers, after all, are concerned with subject, and the story of Armand

des Grieux and Manon is a moving one. Every individual can

probably remember a situation in his life when he found himself in

situations like poor Armand des Grieux, and everybody has sort of met

his Manon once in his life, probably, so there’s a lot of

identification. But then through the season, to repeat this

identification constantly, I think, cannot be very amusing for the

opera goers.

HWH: That would be

rather taxing for the theater goers, wouldn’t it? The theater

goers, after all, are concerned with subject, and the story of Armand

des Grieux and Manon is a moving one. Every individual can

probably remember a situation in his life when he found himself in

situations like poor Armand des Grieux, and everybody has sort of met

his Manon once in his life, probably, so there’s a lot of

identification. But then through the season, to repeat this

identification constantly, I think, cannot be very amusing for the

opera goers.

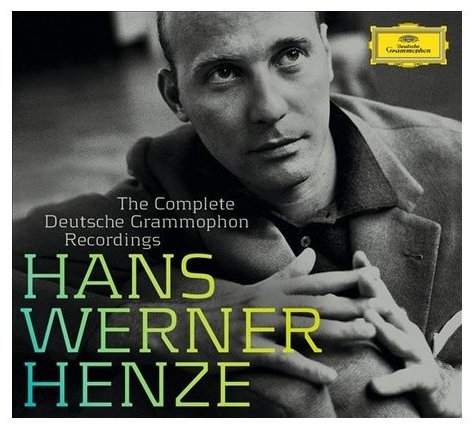

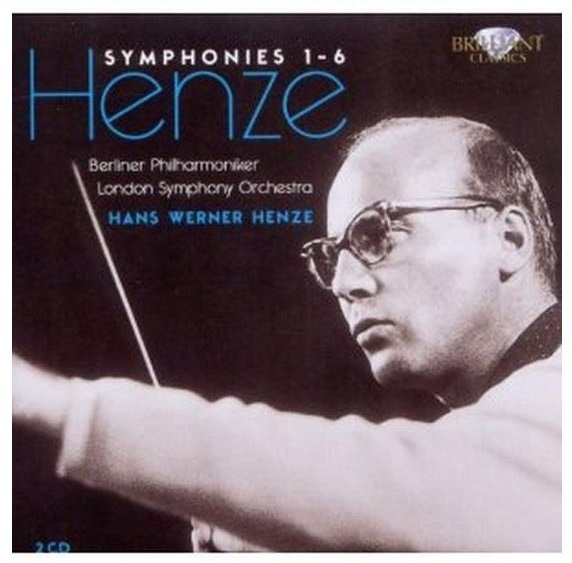

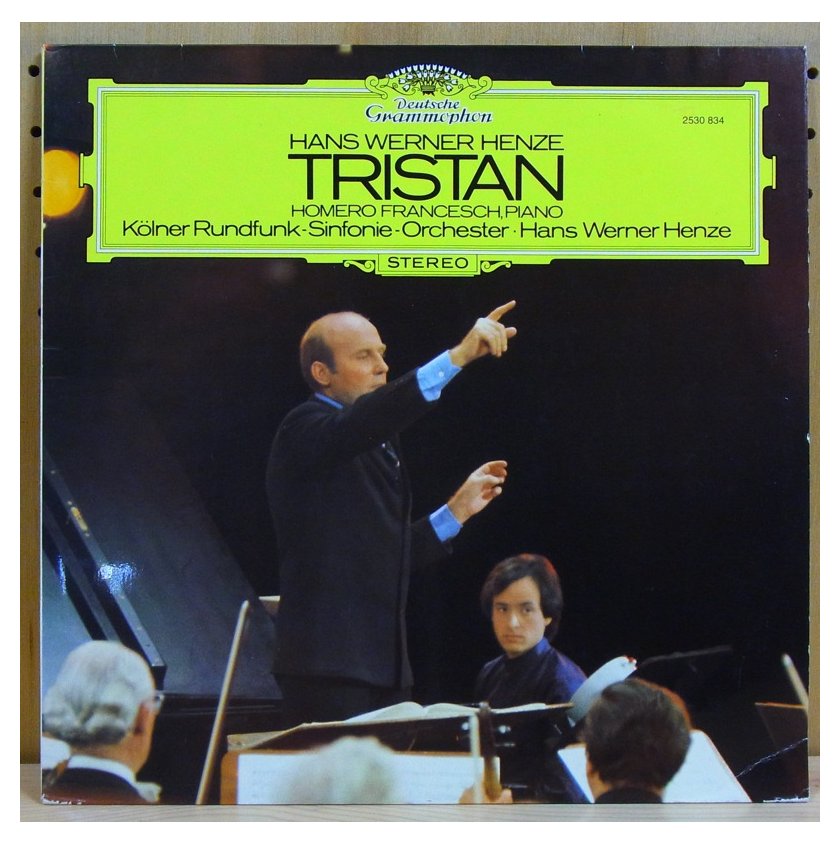

HWH: I try very much

to make this recording a kind of document of the most precise and most

correct rendering of the piece in question. I’ve been able to do

that various times recently with the London Sinfonietta, where the

orchestra is specialized in contemporary music. With their help,

some of my newer works are on record now in an impeccable way.

For instance, there is one recording published by Decca, with Second Violin Concerto and Viola Concerto on it, and there is

a song cycle, Voices, and a

little bit older is a recording of Kammermusik

1958 with Philip Langridge singing and the Sinfonietta

playing.

HWH: I try very much

to make this recording a kind of document of the most precise and most

correct rendering of the piece in question. I’ve been able to do

that various times recently with the London Sinfonietta, where the

orchestra is specialized in contemporary music. With their help,

some of my newer works are on record now in an impeccable way.

For instance, there is one recording published by Decca, with Second Violin Concerto and Viola Concerto on it, and there is

a song cycle, Voices, and a

little bit older is a recording of Kammermusik

1958 with Philip Langridge singing and the Sinfonietta

playing.

|

Hans Werner Henze

By PAUL GRIFFITHS Published in The New York Times, October 28, 2012 Hans Werner Henze, a prolific German composer who came of age in the Nazi era and grew estranged from his country while gaining renown for richly imaginative operas and orchestral works, died on Saturday in Dresden, Germany, where he was due to attend the premiere that evening of a ballet set to one of his scores. He was 86. His longtime publisher, Schott Music, announced his death in a statement. No cause was specified, and no further details were provided. Born into a European generation that wanted to make a fresh start at the end of World War II, Mr. Henze (pronounced HEN-tzuh) did so without wholly negating the past. He wanted a new music that would carry with it the emotion, the opulence and the lyricism of the Romantic era, even if those elements now had to be fought for. Separating himself from the avant-garde, he devoted himself to genres many of his colleagues regarded as outmoded: opera, song, the symphony. By the early 1960s Mr. Henze was an international figure with enthusiastic admirers in the United States. His Fifth Symphony was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, which gave the work’s premiere in 1963, with Leonard Bernstein conducting. More than 40 years later, the orchestra took part in commissioning one of Mr. Henze’s last orchestral works, the tone poem “Sebastian Dreaming.” He maintained relationships with other American institutions as well, including the Boston Symphony, which commissioned his Eighth Symphony (1992-93), and the Tanglewood Music Festival, where he was composer-in-residence in 1988. His music expressed passionate but mixed feelings about his German heritage. His Nazi-era childhood alone would have produced, at the least, ambivalence about that heritage, but his homosexuality only further estranged him, particularly from the bourgeois West German society of the immediate postwar years. And he found little sympathy at home for his embrace of the Romantic past. He had to escape, and in 1953 he abruptly left for Italy. But he went on writing operas for theaters in Germany, where he was far more popular than any other composer of his time. That success brought him material comfort, and he came to give a fair physical impression of the kind of well-to-do burgher he might well have feared and despised in his youth: tight-suited, bald, energetic even when still. What failed to fit this image of stiff propriety was his unfailing charm, his sardonic sense of humor and his fondness for his many friends. As he grew older, the matter of Germany became increasingly important to his music. Having written his Cuban-inflected Sixth Symphony (1969) — produced during a period when he spent a great deal of time in Cuba — he composed his Seventh (1983-84) for the Berlin Philharmonic, taking Beethoven as his model. Again with Beethoven in mind and again writing for the Berlin Philharmonic, he made his Ninth a choral symphony — and a drama — telling a story of desperation and hope set during the Nazi epoch. Hans Werner Henze was born on July 1, 1926, in Gütersloh, Westphalia, in northwest Germany. After army service in 1944 and 1945 he studied with Wolfgang Fortner at the Heidelberg Institute for Church Music and with the French composer René Leibowitz. He soon became acquainted with the modern music that had been banned by the Nazis — notably Stravinsky and Berg, as well as jazz — and gained the means to create a sprightly style that carried him through an abundant youthful output. By the time he was 25 he had written three symphonies, several ballets and his first full-length opera, ”Boulevard Solitude” (1951). In his Second String Quartet (1952) he drew close to his more avant-garde contemporaries, but the moment quickly passed. The next year he left his post as music director of the Wiesbaden State Theater to settle on the Bay of Naples, and his music at once became luxurious and frankly emotional, as exemplified by his fairy-tale opera “King Stag,” first performed in Berlin in 1956. It was an exultant period, which also brought forth his Fourth Symphony (1955); the full-length ballet “Ondine” (1956-57), produced with choreography by Frederick Ashton at Covent Garden; “Nocturnes and Arias,” for soprano and orchestra (1957); and “Chamber Music,” for tenor, guitar and octet (1958). In his next opera, “The Prince of Homburg,” first produced in Hamburg in 1960, he caricatured German militarism within a style fashioned after the bel canto operas of Bellini and Donizetti. After this came “Elegy for Young Lovers,” to a libretto by W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman, about a poet’s use of his family and acquaintances in his art. The story’s alpine setting offered Mr. Henze the opportunity for glistening, radiant music, scored for a chamber orchestra. The work had its first performance in Schwetzingen, Germany, in 1961, and has been more widely seen than any of the composer’s other operas. “The Young Lord,” presented by City Opera in 1973, is the only of one Mr. Henze’s full-length operas to have received a professional staging in New York. (His one-act opera “The End of a World” was presented by Encompass New Opera Theater in 2003.) Working again with Auden and Kallman, he went on to a much bigger operatic project, “The Bassarids,” a remake of Euripides’ “Bacchae,” which was presented at the 1966 Salzburg Festival. The undertaking provoked a creative crisis, out of which Mr. Henze re-emerged as a radical socialist. He had contacts with student leaders, taught and studied in Cuba for a year, and composed several explicitly political works, among them “The Raft of the Medusa” (1968), a semi-dramatic cantata protesting racism and other forms of discrimination, and “El Cimarrón” (1969-70), a concert-length work for baritone, flute, guitar and percussion telling the story of a runaway slave. But once again Mr. Henze moved swiftly on. By the time he composed what might have been his biggest essay in political engagement — the opera “We Come to the River,” with a libretto by the English socialist playwright Edward Bond, produced at Covent Garden in 1976 — his musical interests had returned to his more characteristic moods of nostalgia, reverie, burlesque and erotic passion. Among his other important works of this period is “Tristan” for piano, orchestra and tape (1974), a symphonic poem on the medieval legend including quotations from Wagner’s treatment of it. In 1976 Mr. Henze founded a festival in the small Italian town of Montepulciano, where he pursued his ideals as a musician in society, working with local performers and drawing other, younger composers to do the same. He was extraordinarily open and encouraging to student composers, and there are many whose careers he made by crucial advice or an important break. Further works with Mr. Bond followed: the ballet “Orpheus” (1979) and the surreal-satirical opera “The English Cat” (1983). But “Tristan” had signaled a rapprochement with Germany. From his home near Rome, his principal place of residence since 1961, Mr. Henze made increasingly frequent and lengthy returns to his native country, and in 1988 he established a biennial festival of new music theater in Munich. He had begun his artistic life in the theater, and he found it hard to leave. Having announced that “L’Upupa und der Triumph der Sohnesliebe” (“The Hoopoe and the Triumph of Filial Love,”) which had its premiere in Salzburg in, 2003) would be his last opera, he went on to produce a “Phaedra” for the Berlin State Opera in 2007 and “Gisela!,” an opera for student singers, for the Ruhr Festival in 2010. The crowning work of Mr. Henze’s late period is “Elogium Musicum” for choir and orchestra (2008), which he wrote in memory of Fausto Moroni, his companion of four decades, who died in 2007. At once vast and intimate, Mediterranean-Classical in its sunlight and German-Romantic in its expressive depth, it is also a fitting memorial to its composer. |

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 27,

1981. Portions were broadcast on WNIB 1986 and 1996. A copy

of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This

transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.