| There is an earthy, unmistakably

English quality to Lloyd's music, which by the late 30s had made the

young composer a phenomenon: in 1938, London greeted with astonishment

and acclaim the 25 year old Lloyd, who had composed two operas - Iernin at the Lyceum and The Serf at Covent

Garden - seemingly from nowhere.

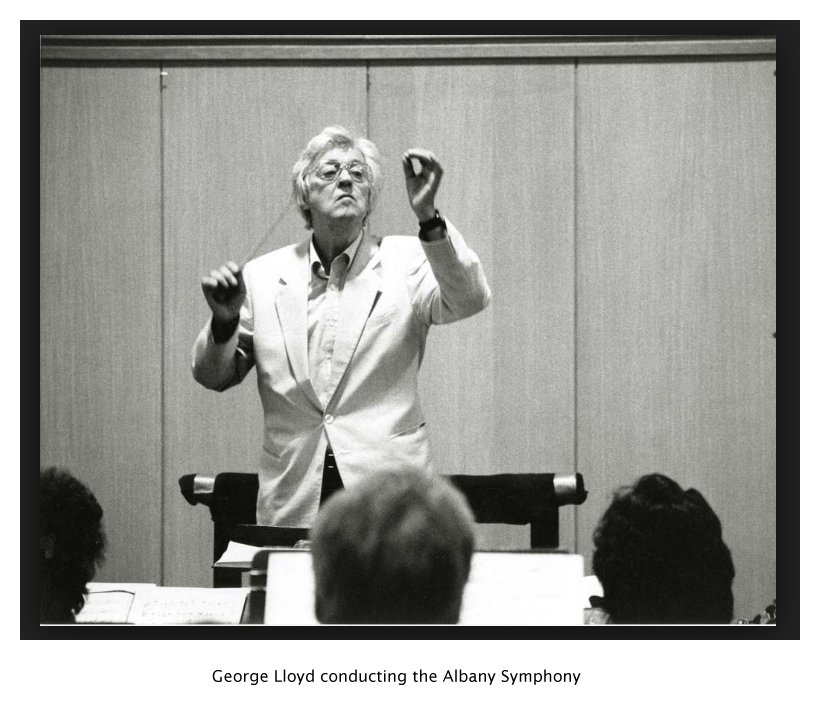

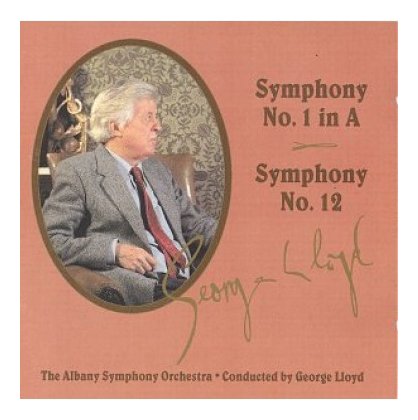

It is telling that George's third opera, John Socman, was one of three commissioned for the Festival of Britain in 1951, alongside works by Britten and Vaughan Williams. However, World War II had left Lloyd physically and psychologically scarred: whilst serving in the Royal Marines - where his long and fruitful association with Band Music began - Lloyd was among the lucky few Bandsmen to survive when his cruiser HMS Trinidad was torpedoed on the Arctic convoys. By the time he could return productively to work, the musical and critical tides had changed dramatically: his former reputation disregarded, George strove alone to continue his work, finding no recognition from an establishment which now saw his work as regressive. It is a credit to George's devotion to his art, and his strong self-belief, that in the last years of his life, following several commissions from the Albany Symphony Orchestra (bringing the number of symphonies to 12!) and the runaway success of his Symphonic Mass, Lloyd's music once again started to reach a larger audience, and receive the critical appreciation it deserved. This can in part be attributed to the enduring appetite of modern audiences for music which is unapologetically melodic - Lloyd's writing is tuneful and easily accessible - but its appeal is more sophisticated than that: his music invites us, unabashed, to share a heartfelt and consuming passion, delivered with exceptional technique in orchestration and clarity of expression. Lloyd's

is deeply personal music, the triumphant product of a life marred by

personal tragedy, and a joyfully defiant response to an increasingly

cynical world.

The obituary which

appeared in The Times is

reproduced at the bottom of this webpage. |

BD: You conducted

this recording?

BD: You conducted

this recording?  GL: Oh, yes,

yes. I’m still writing hard, yes.

GL: Oh, yes,

yes. I’m still writing hard, yes.  GL: No, Twelve.

Working things out before I really got started, with the plan that I

had I knew it would be somewhere in the region of forty minutes, and

it’s going to come out something like that. I was really trying

to write, to some extent, to a certain length. I just didn’t want

to write another thing lasting sixty minutes. That’s an awful lot

of hard work, scoring a symphony of sixty minutes. I said,

“That’s too much. I’ll do one of forty this time.”

GL: No, Twelve.

Working things out before I really got started, with the plan that I

had I knew it would be somewhere in the region of forty minutes, and

it’s going to come out something like that. I was really trying

to write, to some extent, to a certain length. I just didn’t want

to write another thing lasting sixty minutes. That’s an awful lot

of hard work, scoring a symphony of sixty minutes. I said,

“That’s too much. I’ll do one of forty this time.”  BD: Is the music of

George Lloyd great?

BD: Is the music of

George Lloyd great?

BD: You sound like

you’re more of a musical prankster!

BD: You sound like

you’re more of a musical prankster! GL: In a long term,

yes I am. I just don’t

think that you can stop people wanting to sing, wanting to express

themselves. The extraordinary upsurge of people playing

instruments now is really amazing! Consider some of these young

kids that you hear performing! We have a thing in England called

Young Musician of the Year which happens every two years. [Note: This is correct, though neither of

us commented about the irony!] They go round and have

tests in all the different regions, and then finally about a hundred

are pulled out of all these regional competitions. Then they

whittle it down, and this is a great TV show now. They have the

best in different categories — woodwinds,

brass, strings, piano, etcetera, etcetera. This is being done

also on a European basis, so the winners of the national Young Musician

of the Year then compete in the European ones. This past year it

was absolutely uncanny! In England there was a young boy who

played the horn, and he was only fourteen years old. All the horn

players I know just said, “You can’t teach him anything. Whatever

is he going to do? There’s nothing more for him to do.” The

repertoire is limited, and there he was, playing this horn like

nobody’s business.

GL: In a long term,

yes I am. I just don’t

think that you can stop people wanting to sing, wanting to express

themselves. The extraordinary upsurge of people playing

instruments now is really amazing! Consider some of these young

kids that you hear performing! We have a thing in England called

Young Musician of the Year which happens every two years. [Note: This is correct, though neither of

us commented about the irony!] They go round and have

tests in all the different regions, and then finally about a hundred

are pulled out of all these regional competitions. Then they

whittle it down, and this is a great TV show now. They have the

best in different categories — woodwinds,

brass, strings, piano, etcetera, etcetera. This is being done

also on a European basis, so the winners of the national Young Musician

of the Year then compete in the European ones. This past year it

was absolutely uncanny! In England there was a young boy who

played the horn, and he was only fourteen years old. All the horn

players I know just said, “You can’t teach him anything. Whatever

is he going to do? There’s nothing more for him to do.” The

repertoire is limited, and there he was, playing this horn like

nobody’s business. |

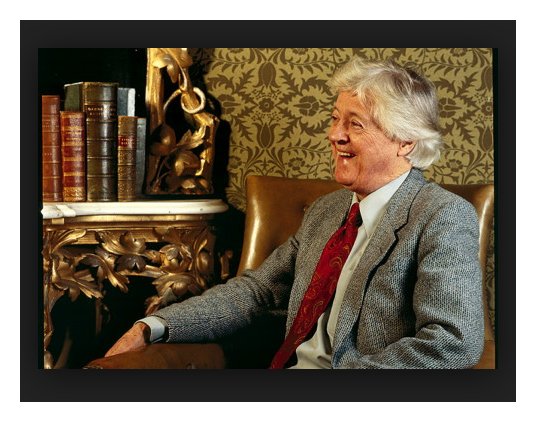

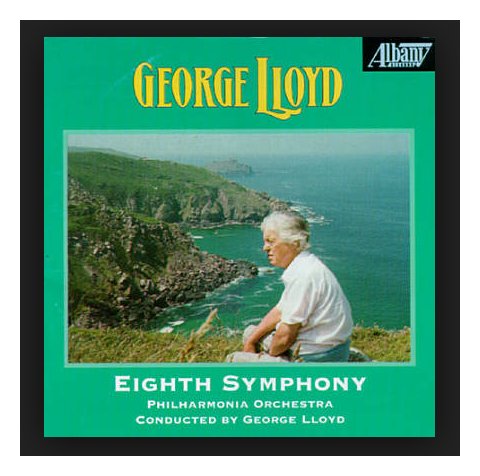

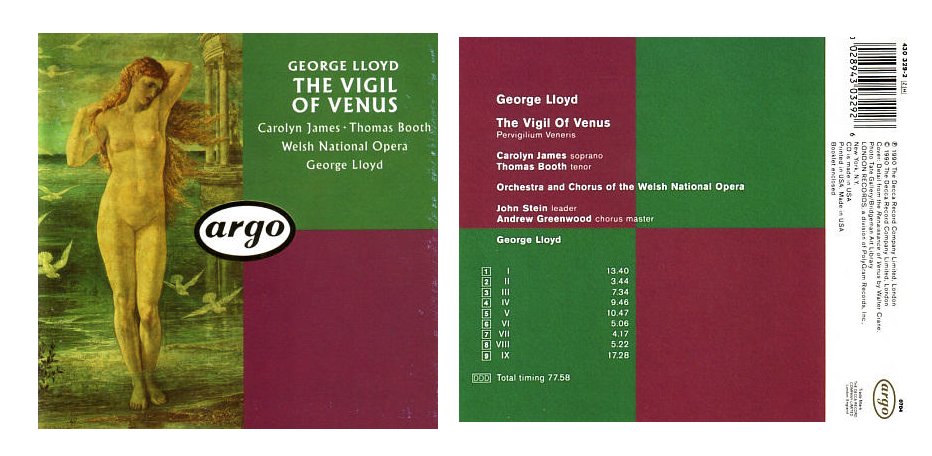

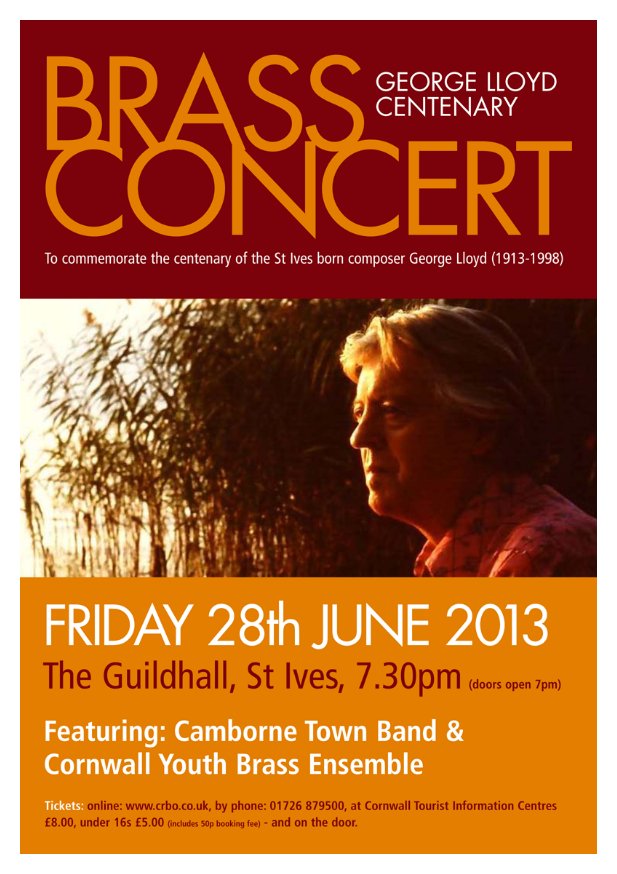

George

Lloyd, Composer

The Times: Monday July 6 1998 George Lloyd, composer died on July 3 aged 85. He was born on June 28th 1913. George Lloyd's long career was a remarkable cycle of recognition and neglect. Prodigiously successful in the 1930s, he saw a promising future blighted first by traumatic wartime service in the Royal Navy, which left him incapacitated for several years, and then by a change in artistic fashion which meant that for decades his compositions went unheard. For a time he gave up on music altogether and became a market gardener instead. Slowly however, he returned to composing and even more slowly his musical fortunes turned. With his health restored and the wider artistic climate transformed, he enjoyed an extraordinary Indian summer in the last two decades of his life. New works were written, recorded and performed. Other pieces were discovered and revived. All were greeted with popular enthusiasm that was almost without parallel in contemporary musical life. Given a chance to hear it at last audiences found that they loved Lloyd's work. It was not hard to understand why. Lloyd was an unashamedly late-Romantic composer. His first love he once said has been for the Italian Operatic masters Verdi, Puccini, Donizetti and Bellini. Elgar was the English composer he most admired. Content to mine the expressive potential melody and harmony in the grand 19th Century tradition, Lloyd rejected the theoretical rigours of 20th Century modernism as a musical dead end. Here was a contemporary composer whose work sounded nothing like most contemporary music. To listeners fond of asking why modern composers are incapable of writing decent tunes, Lloyd's music came as a welcome revelation. But the populist triumphalism of his noisier champions was no more accurate a reflection of his achievements than the grudging response of more professional critics. Conservative though it is in idiom, Lloyd's music is free of easy nostalgia and pastiche. He may have looked to the past for his inspiration, but his response is vital and intensely personal to the world in which he lived. Born in Cornwall to a comfortable family with some money and a great deal of enthusiasm for music, George Walter Selwyn Lloyd missed much of his schooling because of rheumatic fever. He went on to study violin with Albert Sammons and composition with Harry Farjeon. His was a precocious talent. His First Symphony, written when he was 19 was premiered by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra in 1933. Two years later his career was well under way. His Second Symphony had its premier at Eastbourne in 1935 and was followed almost immediately by the Third which the BBC Symphony Orchestra performed. Meanwhile Lloyd's first opera Iernin had been performed in Penzance in 1934. The Times critic, Frank Howes, on holiday in that area, had given a glowing review, which lead to London performances at the Lyceum the following year. A second opera, The Serf was staged at Covent Garden when Lloyd was just 25 under the baton of Albert Coates. The war put a stop to this musical progress. As Royal Marine bandsman, Lloyd doubled as a gunner, serving on the notoriously dangerous Arctic convoys. In 1942 a faulty torpedo did a U-turn in the sea and blew up his ship. Lloyd was rescued but not before he had seen most of his fellow gunners drowned in oil. The trauma and severe shell-shock exacerbated the weak health he had suffered as a child, bringing about a complete collapse. He attempted to come to terms with his grim wartime experience in his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, works which only the devoted nursing of his Swiss-born wife Nancy enabled him to complete (in 1946 and 1948 respectively). Despite the severity of his illness, Lloyd managed to produce a third opera, John Socman, about a Wiltshire soldier at Agincourt. Commissioned for the Festival of Britain in 1951, it had its first performance at Bristol. The libretto, like those for the two previous operas, was provided by his father William Lloyd. Lloyd's health deteriorated further, and in 1952 he withdrew to Dorset where for 20 years he was a market gardener growing mushrooms and carnations. He continued to compose intermittently, rising at 4.30am and writing for three hours before the start of the working day. But he found it difficult to get his work performed and became increasingly disillusioned, seeing himself at odds with a musical establishment apparently in thrall to the serialist and a tonal orthodoxies of European modernism. "I sent scores off to the BBC" he later said. "They came back, usually without comment. I never wrote 12-tone music because I didn't like the theory. I studied the blessed thing in the early 1930s and thought it was a cock-eyed idea that produced horrible sounds. It made composers forget how to sing." Nevertheless, he was not entirely without supporters. Among those who continued to respond to his music's opulence, vigour and colour were the conductors Charles Groves and Edward Downes and the pianist John Ogdon, for whom Lloyd wrote the first of four piano concertos, Scapegoat, in 1963. The tide began to turn albeit slowly. In 1970's Gavin Henderson, then chief executive of the Philharmonia, gave useful support. The BBC, after neglecting Lloyd for years, accepted his Eighth Symphony for performance in 1969 - and finally got round to broadcasting it eight years later. His Sixth Symphony was given at the Proms in 1981,and in the same year three of his symphonies were recorded by Lyrita Records. But perhaps the most influential figure in the recent revival of Lloyd's fortunes was Peter Kermani an American entrepreneur and music lover whose enthusiasm for Lloyd's work led to a deal with the Albany Symphony Orchestra from New York State. This brought forth a flood of performances and recordings of both old and new compositions. It also brought Lloyd a whole new American audience and, in his own delighted words, ""All of a sudden buckets of dollars!" Among the new works recorded were Lloyd's Eleventh and Twelfth Symphonies, which had their first performances in 1986 and 1990. Other major new compositions included a large scale choral piece, The Vigil of Venus, premiered at the Festival Hall in 1989, nine years after its completion, and a Symphonic Mass, premiered at the 1993 Brighton Festival under the baton of the composer. The latter work was described by Gramophone magazine as "one of the finest pieces of English choral writing of the 20th century." The Times critic remarked, not unkindly, on its "overwhelming retrospection". Lloyd suffered heart trouble last year, but recovered sufficiently to resume work on a Requiem, which he completed three weeks ago. He is survived by his wife Nancy whom he married in 1937. They had no children. |

Postscript

-- After uploading this interview to my website, I sent an e-mail

to the George Lloyd Society to let them know of its availability.

A couple of weeks later, I received a message from the nephew of

the composer, William Lloyd, which is hereby reproduced...Dear Bruce, |

This interview was recorded in Chicago on November 8,

1988. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB later that day, and again the following year, and in 1993 and

1998. The

transcription was made and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.