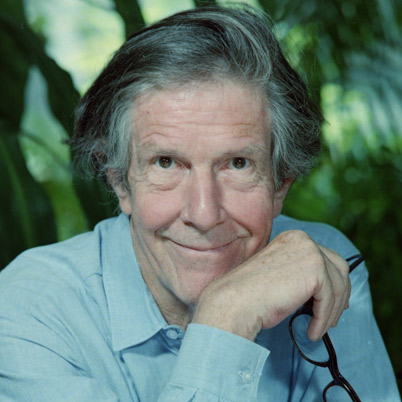

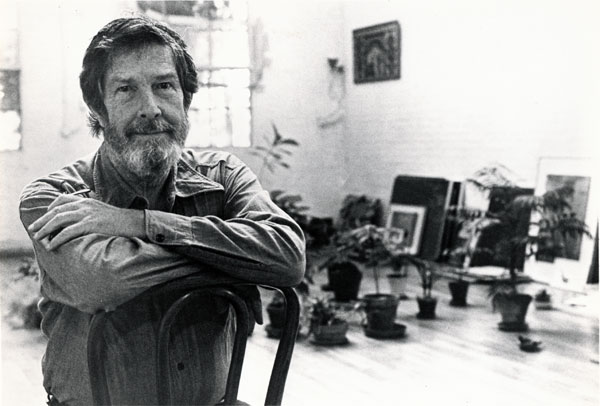

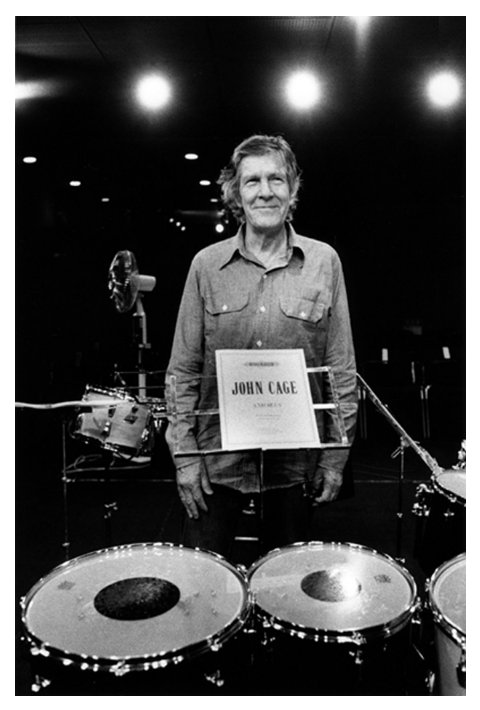

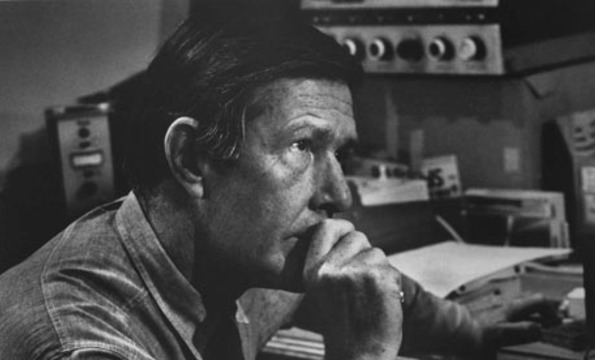

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

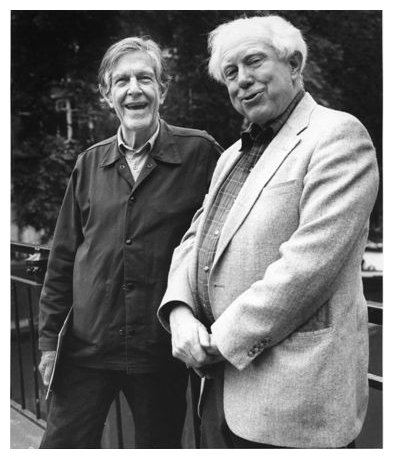

| John Cage was born in Los

Angeles in 1912. He studied with Richard Buhlig, Henry Cowell, Adolph

Weiss, and Arnold Schoenberg. In 1952, at Black Mountain College, he

presented a theatrical event considered by many to have been the first

Happening. He was associated with Merce Cunningham from the early

1940's and was Musical Advisor for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company

until his death in 1992. Cage and Cunningham were responsible for a

number of radical innovations in musical and choreographic

compositions, such as the use of chance operations and the independence

of dance and music. Cage was the recipient of many awards and honors, beginning in 1949 with a Guggenheim Fellowship and an Award from the National Academy of Arts and Letters for having extended the boundaries of music through his work with percussion orchestra and his invention in 1940 of the prepared piano. Cage was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1978, and was inducted into the 50-member American Academy of Arts and Letters in May, 1989. He was named Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Minister of Culture in 1982, and received an Honorary Doctorate of Performing Arts from the California Institute of the Arts in 1986. Cage was the Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University for the 1988-1989 academic year. He was laureate of the 1989 Kyoto Prize given by the Inamori Foundation. In 1987, he wrote, designed and directed Euroceras 1 & 2, with the assistance of Andrew Culver, for the Frankfurt Opera. 101 (1989) was commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Fromm Foundation at Harvard University. Euroceras 3 & 4 was commissioned by the Almeida Music Festival and Modus Vivandi Foundation in 1990. The 1991 Zurich June Festival was devoted to the work of John Cage and James Joyce. Cage is the author of Silence, A Year from Monday, M, Empty Words, and X (all published by the Wesleyan University Press). I-VI (the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures delivered at Harvard in 1988-89) was published by the Harvard University Press in the Spring of 1990. This book includes transcripts of the question and answer periods that followed each lecture, and an audiocassette of Cage reading one of the six lectures. Conversations with Cage, a book-length composition of excerpts from interviews by Richard Kostelantz, was published in 1988 by Limelight Editions. Cage's music is published by the Henmar Press of C. F. Peters Corporation and has been recorded on many labels. Since 1958, many of Cage's scores have been exhibited in galleries and museums. A series of fifty-two watercolors, the New River Watercolors, executed by Cage at the Miles C. Horton Center at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University was shown at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. in April-May, 1990. In 1991, the Cunningham Dance Foundation produced Cage/Cunningham, a documentary film on the collaboration of Merce Cunningham and John Cage, partly funded by PBS, under the direction of Elliot Caplan. John Cage died in New York City on August 12, 1992. |

John Cage: He just left at noon

today with the

Cunningham Dance Company for Japan. He had eaten something that

didn’t agree with

him and he wasn’t sure that he could go.

John Cage: He just left at noon

today with the

Cunningham Dance Company for Japan. He had eaten something that

didn’t agree with

him and he wasn’t sure that he could go.  JC: It’s very hard to answer

that question

because when I tried to get access to any new technologies in the

early forties, I didn’t get it. So it was because of that

that I continued my use of the prepared piano so much. I didn’t

have access to what’s now called high-tech. [Both laugh]

JC: It’s very hard to answer

that question

because when I tried to get access to any new technologies in the

early forties, I didn’t get it. So it was because of that

that I continued my use of the prepared piano so much. I didn’t

have access to what’s now called high-tech. [Both laugh] JC: I don’t think I’m any more

pleased than anybody

else is. In the case of Mozart, for instance, we’re accustomed to

hearing good performances and poor performances. Those

good ones are when the musician pays attention, and the poor ones are

when the attention fails.

JC: I don’t think I’m any more

pleased than anybody

else is. In the case of Mozart, for instance, we’re accustomed to

hearing good performances and poor performances. Those

good ones are when the musician pays attention, and the poor ones are

when the attention fails. BD: Are there ever cases where

performers

find things in your music that you didn’t know were there?

BD: Are there ever cases where

performers

find things in your music that you didn’t know were there? BD: When you’re writing a piece,

there comes a

point where you stop putting notations on the paper. How do you

know when you’ve arrived at that point?

BD: When you’re writing a piece,

there comes a

point where you stop putting notations on the paper. How do you

know when you’ve arrived at that point? BD: Can you tell me a little

bit about that?

BD: Can you tell me a little

bit about that? BD: You must know how they

sound, though?

BD: You must know how they

sound, though?

|

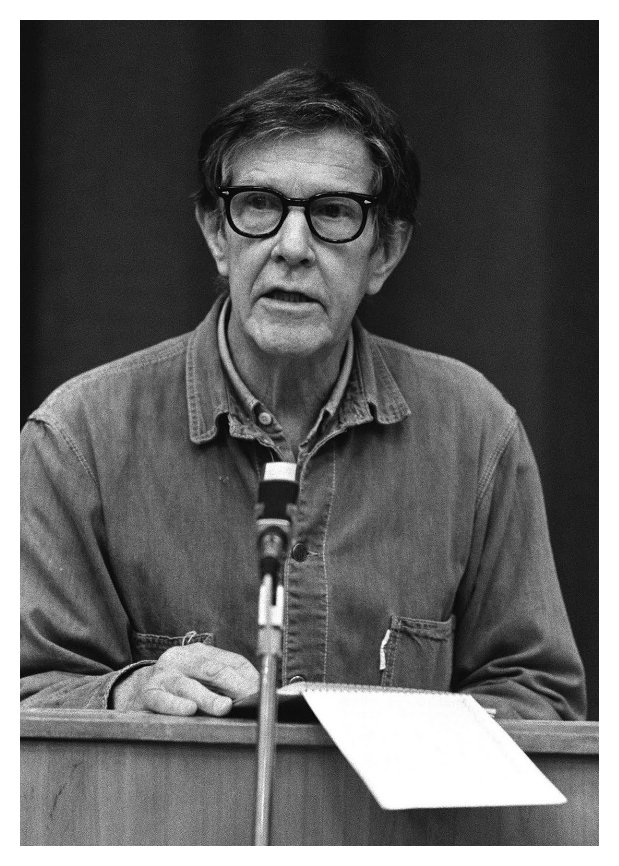

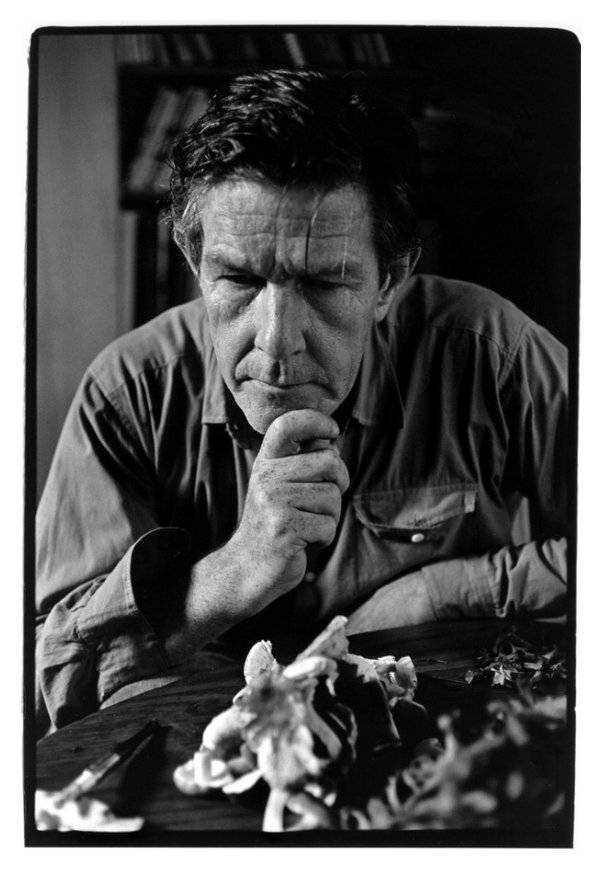

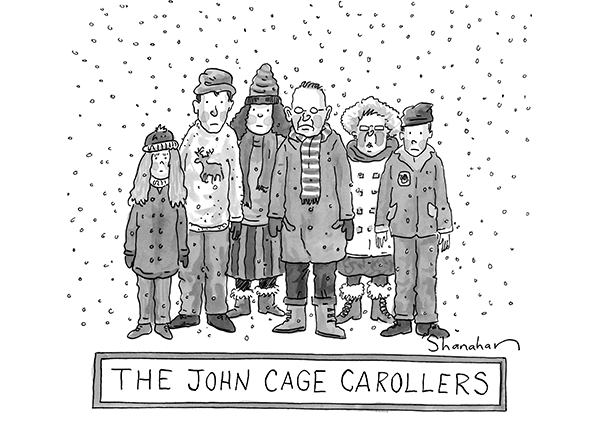

John Cage Biography

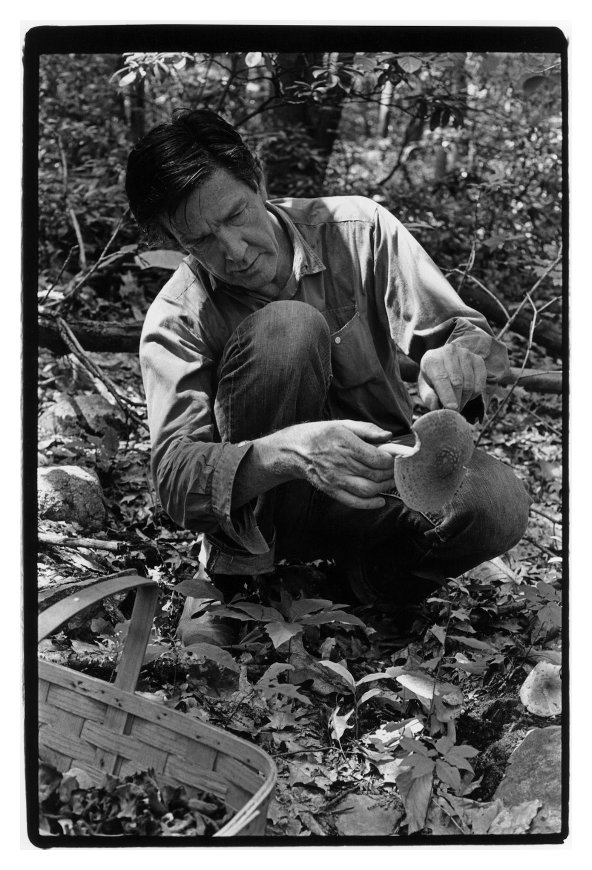

John Milton Cage (September 5, 1912 - August 12, 1992) was an

experimental music composer and writer, possibly best known (some might

say notorious) for his piece 4′ 33″, often described (somewhat

erroneously) as "four and a half minutes of silence." He was an early

writer of aleatoric music (music where some elements are left to

chance), used instruments in non-standard ways and was an electronic

music pioneer.Cage was born in Los Angeles. His father was a somewhat eccentric inventor of largely useless devices who told him "that if someone says 'can't' that shows you what to do." Cage described his mother as a woman with "a sense of society" who was "never happy." It was not obvious from his early life that he would become a composer; he was born into a Episcopalian family, and his paternal grandfather regarded the violin as the "instrument of the devil". Cage himself planned to become a minister at an early age and later a writer. Although music was not clearly to be his chosen path, he did say later that he had unfocused desire to create, and his subsequent anti-establishment stance may be seen to have its roots in an incident while he was attending Pomona College. Shocked to find a large number of students in the library reading the same set text, he rebelled and "went into the stacks and read the first book written by an author whose name began with Z. I received the highest grade in the class. That convinced me that the institution was not being run correctly." He dropped out in his second year and sailed to Europe, where he stayed for eighteen months. It was there that he wrote his first pieces of music, but upon hearing them he found he didn't like them, and he left them behind on his return to America.  He returned to California in 1931, his enthusiasm for

America revived, he said, by reading Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass.

There he took lessons in composition from Richard Buhlig, Henry Cowell,

Adolf Weiss, and, famously, Arnold Schoenberg whom he "literally

worshipped." Schoenberg told Cage he would tutor him for free on the

condition he "devoted his life to music." Cage readily agreed, but

stopped lessons after two years when it became clear to him that he had

"no feeling for harmony." He returned to California in 1931, his enthusiasm for

America revived, he said, by reading Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass.

There he took lessons in composition from Richard Buhlig, Henry Cowell,

Adolf Weiss, and, famously, Arnold Schoenberg whom he "literally

worshipped." Schoenberg told Cage he would tutor him for free on the

condition he "devoted his life to music." Cage readily agreed, but

stopped lessons after two years when it became clear to him that he had

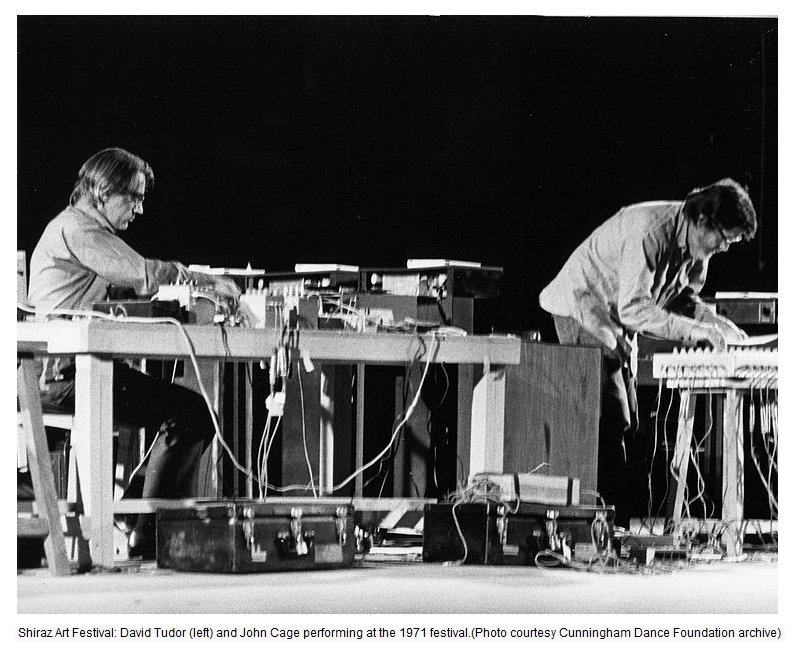

"no feeling for harmony."Cage began to experiment with percussion instruments and non-instruments and gradually came to replace harmony as the basis of his music with rhythm. More generally, he structured pieces according to the duration of sections. He saw a precedent in this in the music of Anton Webern to some extent, but especially in the music of Erik Satie, one of his favourite composers. In the late 1930s, he went to the Cornish School of the Arts in Seattle, Washington. There he found work as an accompanist for dancers. He was asked to write some music to accompany a dance by Syvilla Fort called Bacchanale. He wanted to write a percussion piece, but there was no pit at the performance venue for a percussion ensemble and he had to write for a piano. While working on the piece, Cage experimented by placing a metal plate on top of the strings of the instrument. He liked the sound this produced, and this eventually led to his inventing the prepared piano, in which screws, bolts, strips of rubber and other objects are placed between the strings of the piano to change the character of the instrument. It is likely that he was influenced by his old teacher Henry Cowell who also treated the piano in a non-standard way, asking performers to strum the strings with their fingers, for example. The Sonatas and Interludes of 1946-48 are widely seen as his greatest work for prepared piano. Pierre Boulez was amongst its admirers, and organised the European premiere of the work. The two composers struck up a correspondence, but this stopped when they came to a disagreement over Cage's use of chance in his music. It was also at Cornish that Cage founded a percussion orchestra for which he wrote his First Construction (In Metal) in 1939, a piece which uses metal percussion instruments to make a loud and rhythmic music. He also wrote the Imaginary Landscape No. 1 in that year, which uses record players as instruments, one of the first, if not the first, examples of this. Cage wrote a number of other Imaginary Landscape pieces in later years. While at the Cornish School, Cage became interested in many things which informed much of his later work. He learnt from Gira Sarabhai that "The purpose of music is to sober and quiet the mind, thus making it susceptible to divine influences." This got him writing music again after a period of uncertainty about the value of trying to "express" anything through music. He became interested in Hinduism and Zen Buddhism, and met the dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, who became his life partner and creative collaborator. After leaving the Cornish School, Cage joined the faculty of the Chicago School of Design. While there he was asked to write a sound effects-based musical accompaniment for Kenneth Patchen's radio play The City Wears a Slouch Hat. Cage then moved to New York City, but found it very hard to get work there. However, he continued to write music, and establish new musical contacts. He toured America with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company several times, and also toured Europe with the experimental pianist (and later composer) David Tudor, who he worked with closely many other times. Cage began to use the I Ching in the composition of his music in order to introduce an element of chance over which he would have no control. He used it, for example, in the Music of Changes for solo piano in 1951, to determine which notes should be used and when they should sound. He used chance in other ways as well; Imaginary Landscape No. 4 (1951) is written for twelve radio receivers. Each radio has two players, one to control the frequency the radio is tuned to, the other to control the volume level. Cage wrote very precise instructions in the score about how the performers should set their radios and change them over time, but he could not control the actual sound coming out of them, which was dependent on whatever radio shows were playing at that particular place and time of performance. In 1948, Cage joined the faculty of the Black Mountain College, where he regularly worked on collaborations with Merce Cunningham. Around this time, Cage visited the anechoic chamber at Harvard University. An anechoic chamber is a room designed in such a way that the walls, ceiling and floor will absorb all sounds made in the room, rather than bouncing them back as echoes. They are also generally soundproofed. Cage entered the chamber expecting to hear silence, but as he wrote later, he "heard two sounds, one high and one low. When I described them to the engineer in charge, he informed me that the high one was my nervous system in operation, the low one my blood in circulation." Whatever the truth of these explanations, Cage had gone to a place where he expected there to be no sound, and yet there was some. "Until I die there will be sounds. And they will continue following my death. One need not fear about the future of music." The realisation as he saw it of the impossibility of silence led to the composition of his most notorious piece, 4′ 33″. Another cited influence for this piece came from the field of the visual arts. Cage's friend and Black Mountain colleague Robert Rauschenberg had, while working at the college, produced a series of 'white' paintings. These were apparently 'blank' canvases that, in fact, changed according to varying light conditions in the rooms in which they were hung, the shadows of people in the room and so on. These paintings inspired Cage to use a similar idea, using the 'silence' of the piece as an 'aural blank canvas' to reflect the dynamic flux of ambient sounds surrounding each performance.  The premiere of the three-movement 4′ 33″ was given by

David Tudor on August 29, 1952, at Woodstock, New York as part of a

recital of contemporary piano music. The audience saw him sit at the

piano, and lift the lid of the piano. Some time later, without having

played any notes, he closed the lid. A while after that, again having

played nothing, he lifted the lid. And after a period of time, he

closed the lid once more and rose from the piano. The piece had passed

without a note being played, in fact without Tudor or anyone else on

stage having made any deliberate sound, although he timed the lengths

on a stopwatch while turning the pages of the score. Richard

Kostelanetz suggests that the very fact that Tudor, a man known for

championing experimental music, was the performer, and that Cage, a man

known for introducing unexpected non-musical noise into his work, was

the composer, would have led the audience to expect unexpected sounds.

Anybody listening intently would have heard them: while nobody produces

sound deliberately, there will nonetheless be sounds in the concert

hall (just as there were sounds in the anechoic chamber at Harvard). It

is these sounds, unpredictable and unintentional, that are to be

regarded as constituting the music in this piece. The piece remains

controversial to this day, and is seen as challenging the very

definition of music. The premiere of the three-movement 4′ 33″ was given by

David Tudor on August 29, 1952, at Woodstock, New York as part of a

recital of contemporary piano music. The audience saw him sit at the

piano, and lift the lid of the piano. Some time later, without having

played any notes, he closed the lid. A while after that, again having

played nothing, he lifted the lid. And after a period of time, he

closed the lid once more and rose from the piano. The piece had passed

without a note being played, in fact without Tudor or anyone else on

stage having made any deliberate sound, although he timed the lengths

on a stopwatch while turning the pages of the score. Richard

Kostelanetz suggests that the very fact that Tudor, a man known for

championing experimental music, was the performer, and that Cage, a man

known for introducing unexpected non-musical noise into his work, was

the composer, would have led the audience to expect unexpected sounds.

Anybody listening intently would have heard them: while nobody produces

sound deliberately, there will nonetheless be sounds in the concert

hall (just as there were sounds in the anechoic chamber at Harvard). It

is these sounds, unpredictable and unintentional, that are to be

regarded as constituting the music in this piece. The piece remains

controversial to this day, and is seen as challenging the very

definition of music.4′ 33″ has been recorded on several occasions, one version being "performed" by Frank Zappa (part of A Chance Operation: The John Cage Tribute, on the Koch label, 1993). An 'orchestral' version of 4′ 33″ given by the BBC Symphony Orchestra was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 in January 2004. Cage went on to write such pieces as Aria (1958), HPSCHD (1967-69), Roaratorio: An Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake (1979) and the various so called "numbers pieces" (from the 1980s). He also wrote several books, including Silence (1961), A Year From Monday (1968), M (1973), Empty Words (1979) and X (1983). During his later years, Cage remained experimental, combining many of his musical and free-form concepts in public workshops. Another of Cage's works, Organ² / ASLSP, is currently being performed near the German township of Halberstadt; in accordance with Cage's directions for the piece to be played "As SLow aS Possible", the performance, being done on a specially-constructed autonomous organ built into the old church of St. Burchardi, is scheduled to take a total of 639 years after having been started at midnight September 5, 2001. John Cage died in New York City on August 12, 1992. |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on

June 21, 1987. It

was used (along with recordings) on WNIB in 1987, 1992, and 1997.

An unedited audio copy was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University, and also in

the Oral History American Music

archive at Yale University.

It was transcribed and posted on this

website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.